|

Label: Centro Independiente De Investigaciones Musicales Y Multimedia (CIIMM) SERIES IV, MA-347 |

Country: Mexico Genre: Folk World & Country |

Info:

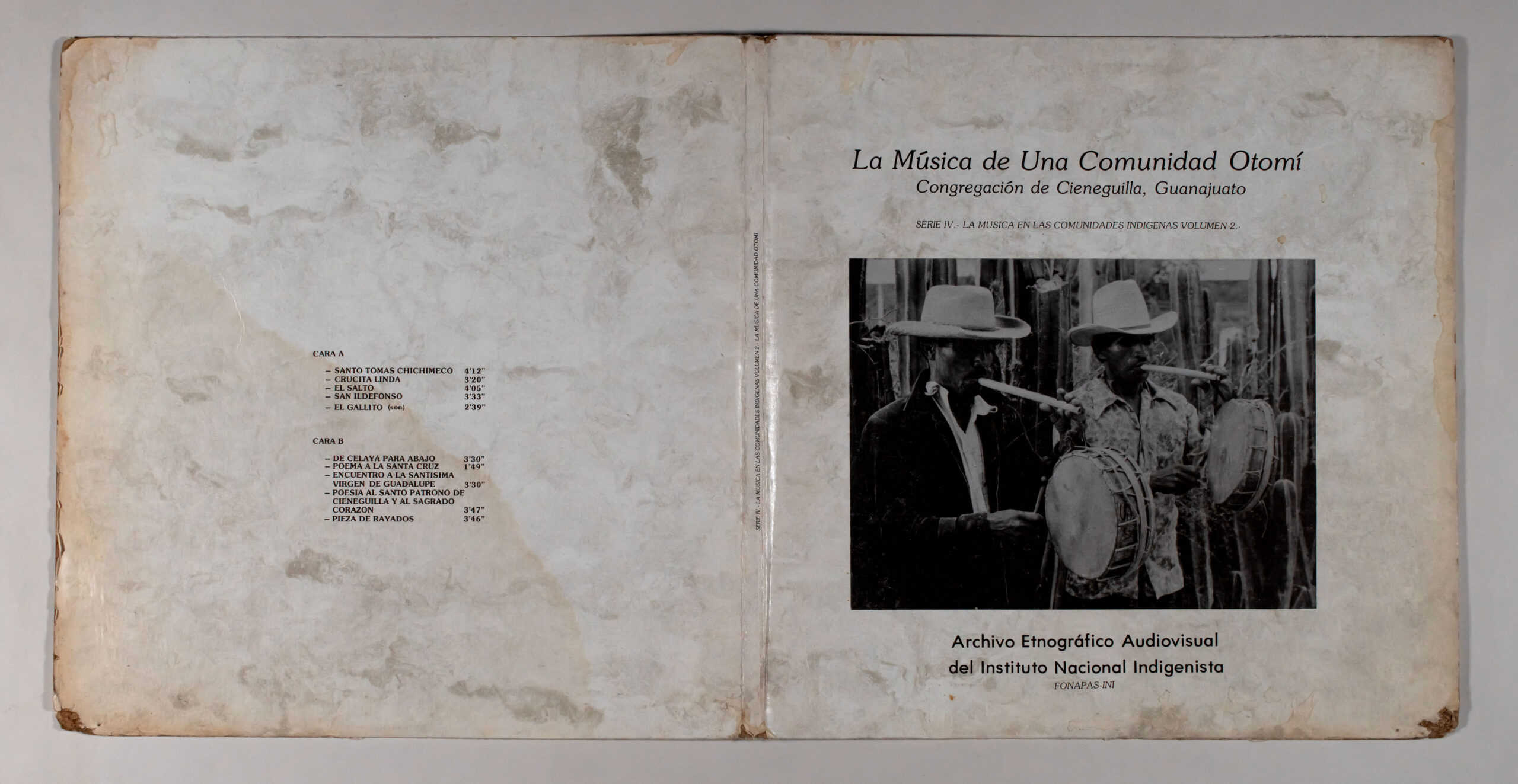

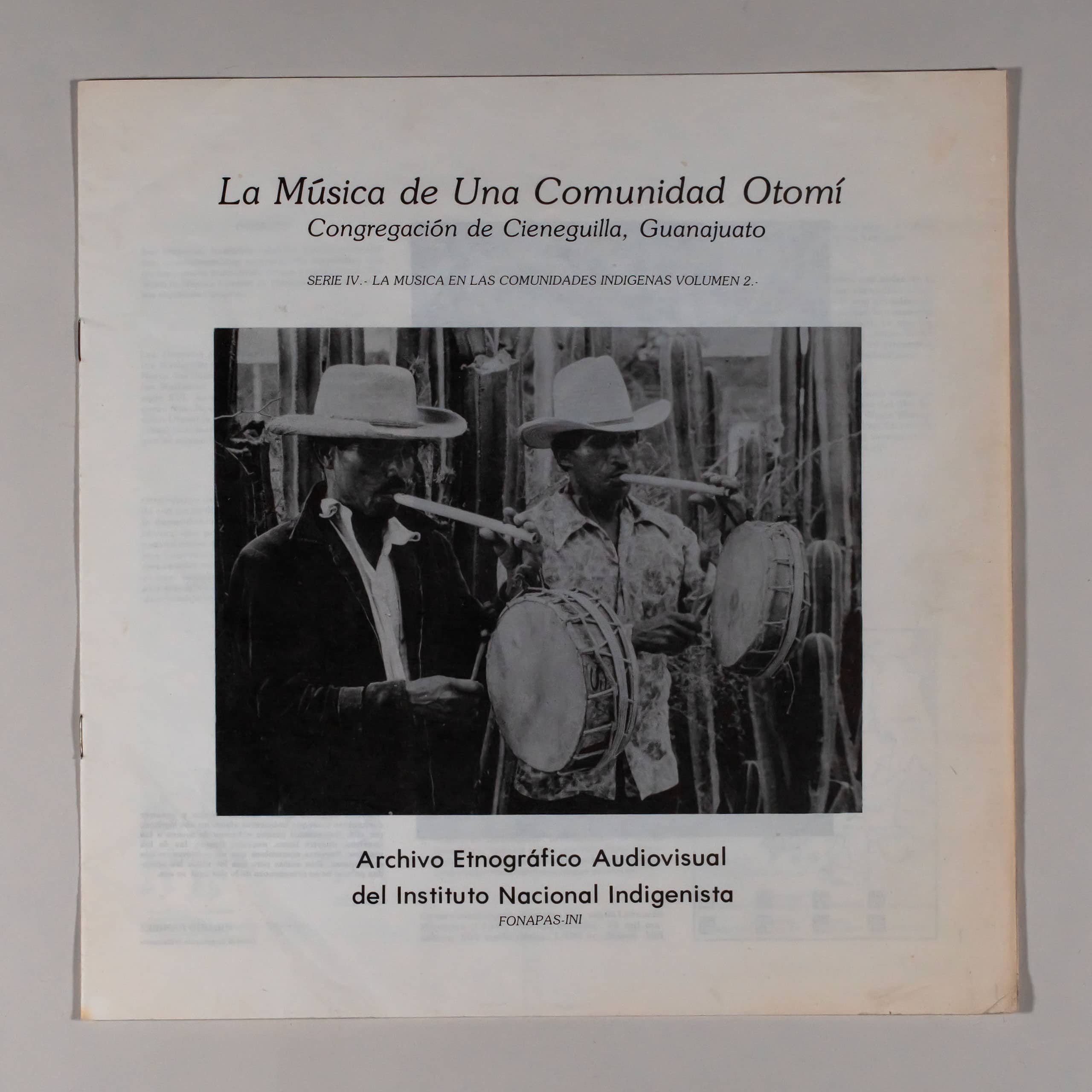

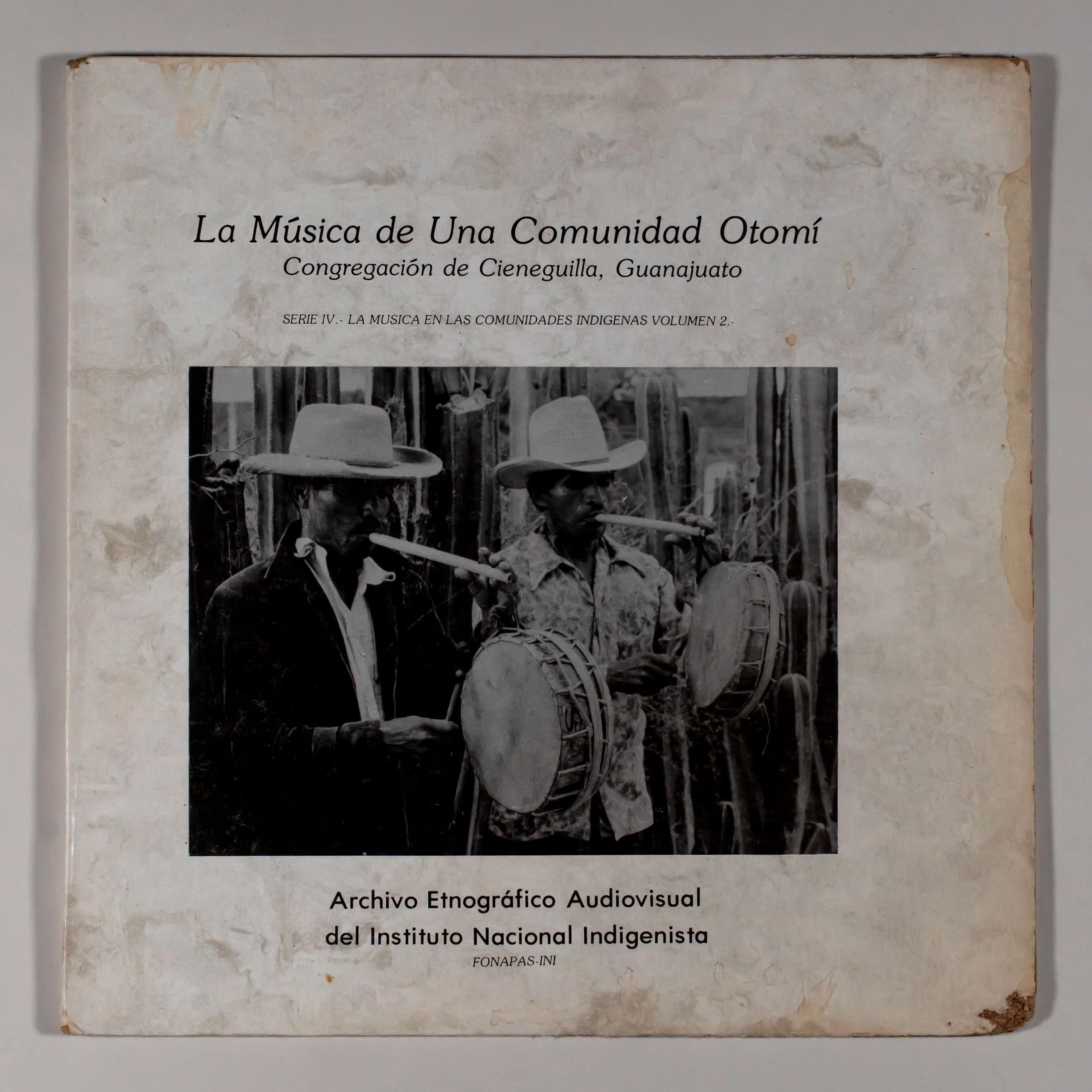

The Music of an Otomi Community

Congregation of Cieneguilla, Guanajuato

SERIES IV.- MUSIC IN INDIGENOUS COMMUNITIES VOLUME 2.-

Audiovisual Ethnographic Archive of the National Indigenous Institute

FONAPAS-INI

We feel a lot about our music and our customs and even though we work abroad we don’t get caught up there. We return because we miss ours, our land, our festivals, those of the saints. Our customs that we do not want to be forgotten. They are anxious for the children to learn them so that they are not ashamed of what is used here.

HILARIO RAMIREZ

Otomi of Congregation of Cieneguilla

OTOMIES

The Otomíes, also called Otomíes or Otomítes, constitute a linguistic macrofamily that includes several peoples of pre-Hispanic origin. They inhabit the Central Plateau of Mexico and are made up of the following groups:

The Otomi proper, the Mazahuas, the Matlatzincas, the Ocuiltecos, the Pames del Norte, the Pames del Sur, the Chichimecas-Jonaz and the Matlames, the latter disappeared in the 16th century. Previously they referred to themselves as Nian Nyu (the one who speaks the language), but the term Otomí (or Otomíte, as the Aztecs called them) they took, according to Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, from an ancestor caudillo named Otón.

Another version of Fray Juan de Torquemada agrees with this one and says: “… In order to make understand the dependency, origin and principle of these Nations, which populated New Spain, it was almost common saying of all, that they had him in an old and venerable old man, named Iztac Mixcuatl, who resided in that place called Siete Cuevas, who, being married to Ilancueitl, had six children from her… and from the last son named Otomitl, the Otomi descended”.

These peoples live between 19° and 23° north latitude and at more than 1,000 meters of altitude, in the following regions:

a) Sierra de las Cruces, west of the Valley of Mexico.

b) Sierra del Ajusco, where the only surviving Ocuilteco towns are located: San Juan Atzingo and Toto.

c) Toluca-Ixtlahuaca Plateau. The Otomi inhabit the North and East of the City of Toluca, and in the remaining parts the Mazahuas and Matlatzincas; Of the latter, only the settlement of San Francisco Oxtotilpan remains, at the foot of the Nevado.

d) Western escarpment of the central plateau.

e) Plains of Querétaro and Hidalgo interrupted by the Sierra de Imam.

f) Sierra Gorda, between the Moctezuma rivers to the south and the Santa María river to the north, both tributaries of the Pánuco. In the southern part, the Otomi and Pames del Sur inhabit (these in Jalpan and Pacula) and in the north, the Pames del Norte.

g) The Laja River Valley.

h) Sierra de Puebla, continuation of the Sierra Madre Occidental to the south of Sierra Gorda.

i) Ixtenco, an isolated settlement in the State of Tlaxcala, at the foot of La Malinche.

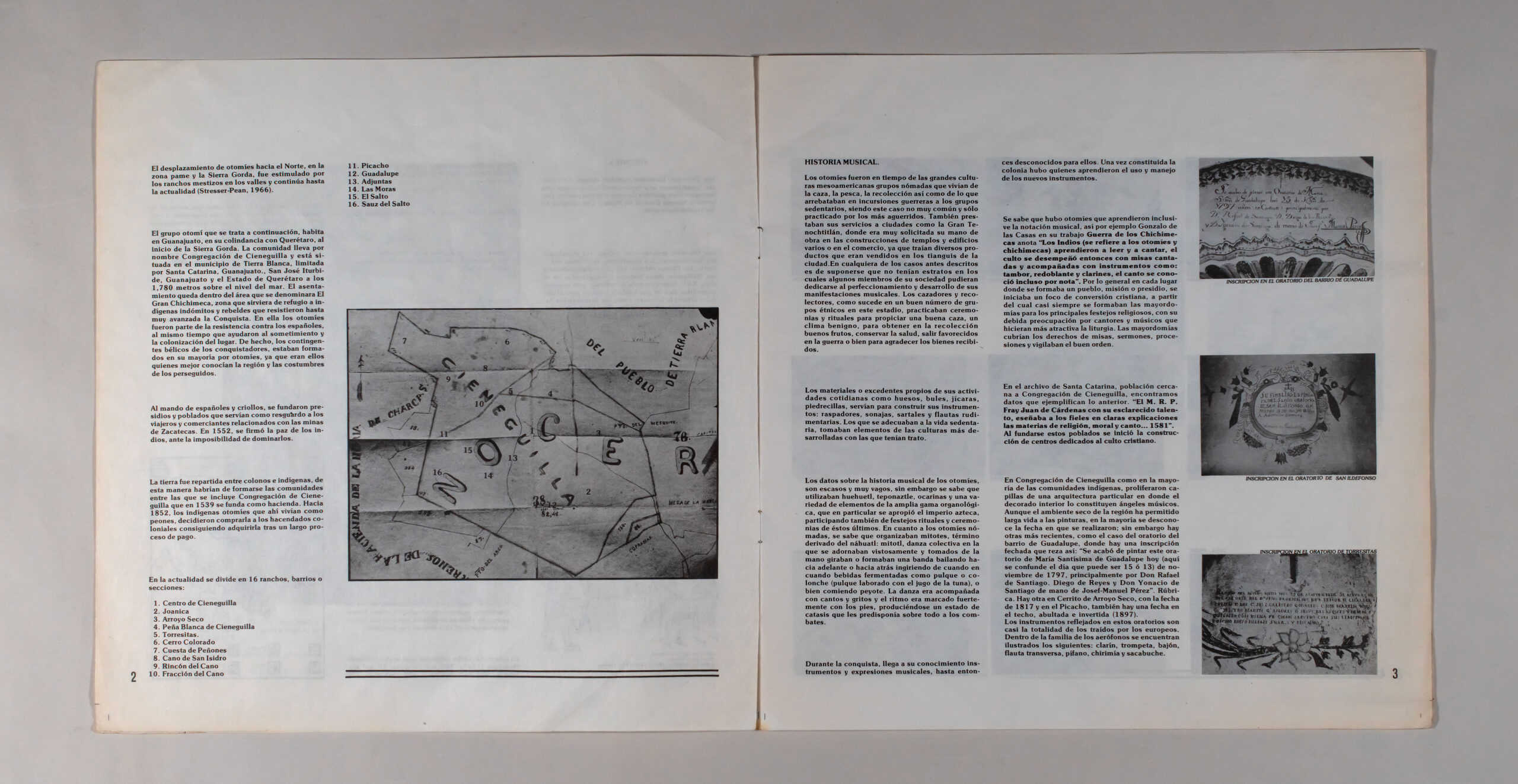

j) Plans of Guanajuato, extension of those of Querétaro, although without homogeneous Otomi occupation; they are also the only remaining Chichimeca settlements.

In this vast region, according to Leonardo Manrique (1969), there are still 300,000 Otomi, 70,000 Mazahuas, 500 Matlatzincas, 1,500 Ocuiltecos, 300 Pame from the South, 2,500 Pame from the North, and 1,600 Chichimeca-Jonaz, that is, a total of 376,400.

Driver and Massey (1957) argue that before the conquest the Otomi had expanded into a larger area of the Altiplano than they currently occupy. Upon the arrival of the Spanish, expansion continued, albeit in a forced manner, as the conquistadors settled in sedentary farming communities in order to protect themselves from the onslaughts of irreducible nomads.

The towns that were founded in the Otomi area at that time were: Querétaro, San Juan del Río, Tolimán, San Miguel Allende, Xichú, Tierra Blanca, Santa María del Río and San Luis de la Paz. In this last place, around the mission, the Chichimecas-Jonaz settled and still remain there.

The displacement of Otomi towards the North, in the Pame zone and the Sierra Gorda, was stimulated by the mestizo ranches in the valleys and continues to the present (Stresser-Pean, 1966).

The Otomí group that is discussed below lives in Guanajuato, on its border with Querétaro, at the beginning of the Sierra Gorda. The community is called Congregación de Cieneguilla and is located in the municipality of Tierra Blanca, bordered by Santa Catarina, Guanajuato, San José Iturbide, Guanajuato and the State of Querétaro at 1,780 meters above sea level. The settlement is within the area called El Gran Chichimeca, an area that served as a refuge for indomitable indigenous people and rebels who resisted until very advanced in the Conquest. In it, the Otomi were part of the resistance against the Spanish, at the same time that they helped to subjugate and colonize the place. In fact, the conquistadors’ military contingents were made up mostly of Otomi, since they were the ones who best knew the region and the customs of the persecuted.

Under the command of Spaniards and Creoles, prisons and towns were founded that served as shelter for travelers and merchants related to the Zacatecas mines. In 1552, the peace of the Indians was signed, given the impossibility of dominating them.

The land was distributed between settlers and indigenous people, in this way the communities would have to be formed, among which the Congregation of Cieneguilla is included, which in 1539 was founded as a hacienda. Around 1852, the Otomi indigenous people who lived there as laborers decided to buy it from the colonial landowners, managing to acquire it after a long payment process.

Currently it is divided into 16 ranches, neighborhoods or sections:

- Downtown Cieneguilla

- Joanica

- Dry Creek

- White Rock of Cieneguilla

- Turrets.

- Colorado Hill

- Rocky slope

- Cano de San Isidro

- Cano corner

- Fraction of Cano

- Peak

- Guadeloupe

- Attached

- The Blackberries

- The jump

- Willow of the Jump

MUSIC STORY.

The Otomi were, in the time of the great Mesoamerican cultures, nomadic groups that lived from hunting, fishing, gathering, as well as from what they took from sedentary groups in war raids, this being not a very common case and only practiced by the most seasoned. . They also provided their services to cities such as Greater Tenochtitlán, where their labor was in great demand in the construction of temples and various buildings or in commerce, since they brought various products that were sold in the city’s tianguis. In any of the cases described above, it is to be assumed that they did not have strata in which some members of their society could dedicate themselves to the improvement and development of their musical manifestations. Hunters and gatherers, as it happens in a good number of ethnic groups in this stage, practiced ceremonies and rituals to promote a good hunt, a mild climate, to obtain good fruits in gathering, to preserve health, to be favored in war or good to thank the goods received.

The materials or surpluses typical of their daily activities such as bones, bules, gourds, stones, were used to build their instruments: scrapers, rattles, strings and rudimentary flutes. Those who adapted to a sedentary life took elements from the more developed cultures with which they had contact.

The data on the musical history of the Otomi are scarce and very vague, however it is known that they used huehuetl, teponaztli, ocarinas and a variety of elements from the wide range of organology, which the Aztec empire in particular appropriated, also participating in ritual celebrations and ceremonies of the latter. As for the nomadic Otomi, it is known that they organized mitotes, a term derived from the Nahuatl: mitotl, a collective dance in which they ornately adorned themselves and holding hands, turned or formed a band dancing forwards or backwards, drinking drinks from time to time. fermented as pulque or colonche (pulque made with tuna juice), or eating peyote. The dance was accompanied by songs and shouts and the rhythm was marked strongly with the feet, producing a state of catharsis that predisposed them above all to combat.

During the conquest, musical instruments and expressions, hitherto unknown to them, came to their knowledge. Once the colony was established, there were those who learned the use and management of the new instruments.

It is known that there were Otomi who even learned musical notation, for example, Gonzalo de las Casas in his work Guerra de los Chichimecas notes “The Indians (referring to the Otomi and Chichimecas) learned to read and sing, the cult then performed with masses sung and accompanied by instruments such as drums, snares and bugles, the singing was even known by note”. In general, in each place where a town, mission or presidio was formed, a focus of Christian conversion began, from which the mayordomías were almost always formed for the main religious festivities, with due concern for singers and musicians who performed liturgy more attractive. The mayordomías covered the rights of masses, sermons, processions and watched over good order.

In the archive of Santa Catarina, a town close to Congregación de Cieneguilla, we found data that exemplify the above. “M. R. P. Fray Juan de Cárdenas, with his enlightened talent, taught the faithful in clear explanations the matters of religion, morals and singing… 1581”. When these towns were founded, the construction of centers dedicated to Christian worship began.

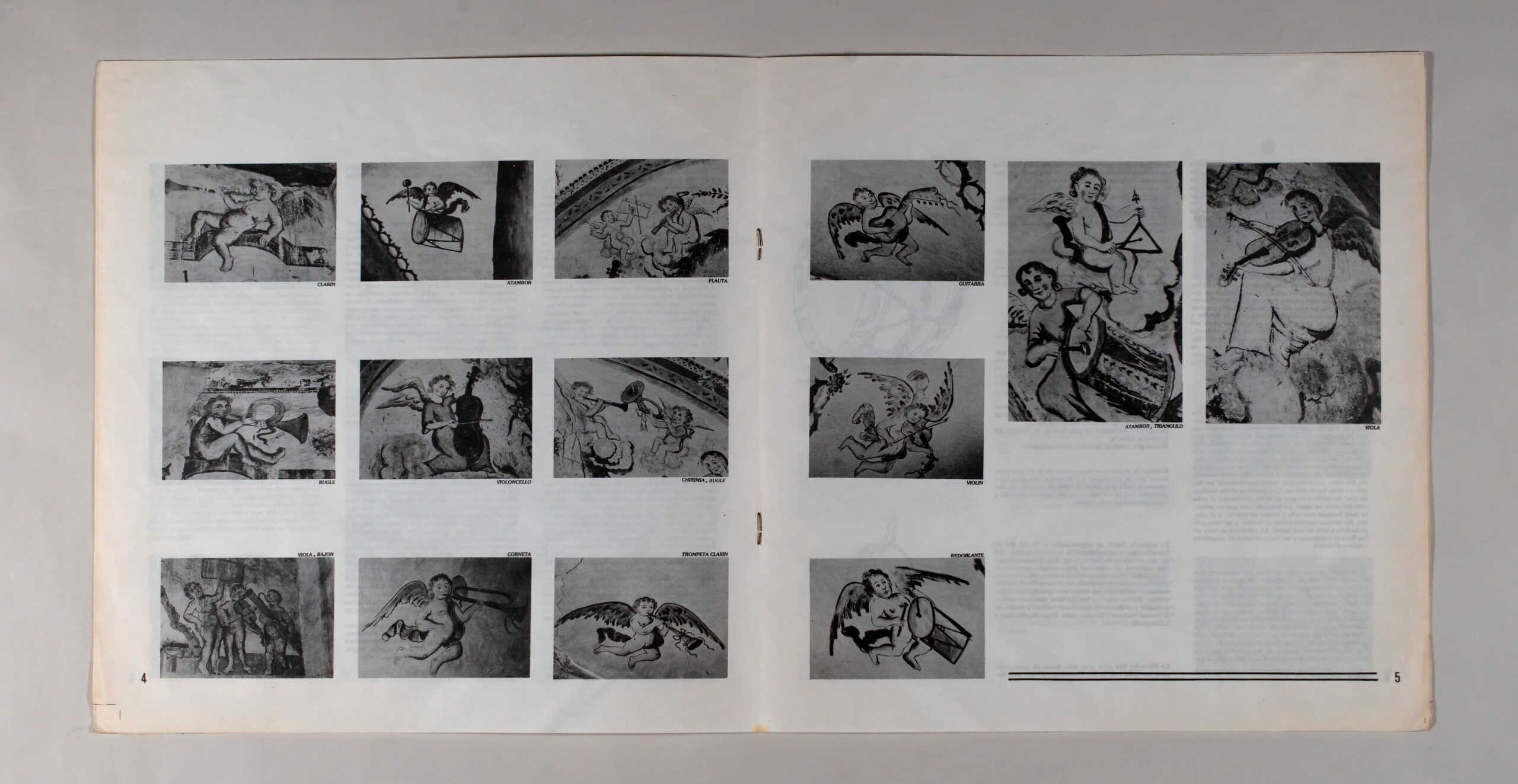

In Congregación de Cieneguilla, as in most indigenous communities, chapels of a particular architecture proliferated where the interior decoration is made up of musical angels. Although the dry environment of the region has allowed the paintings a long life, the date on which they were made is unknown in most; However, there are other more recent ones, such as the case of the oratory in the Guadalupe neighborhood, where there is a dated inscription that reads as follows: “This oratory of María Santísima de Guadalupe was finished painting today (here the day that could be 15 6 is confused 13) of November 1797, mainly by Don Rafael de Santiago, Diego de Reyes and Don Yonacio de Santiago by Josef-Manuel Pérez”. Rubric. There is another in Cerrito de Arroyo Seco, with the date of 1817 and in the Picacho, there is also a date on the roof, bulging and inverted (1897).

The instruments reflected in these oratorios are almost all those brought by the Europeans. Within the family of aerophones, the following are illustrated: clarion, trumpet, bassoon, transverse flute, fife, shawm and sackbut.

Of the membranophones there are drums and drums. Of idiophones: triangle and cymbals. Of chordophones: violin, viola, violoncello, viola de gamba, double bass, guitar, vihuela and harp. It is not possible to affirm if the Otomi made use of all of these instruments, although from the illustrations described above, which were made with great precision and knowledge of the instruments represented, it is known that they came to know them, at least graphically.

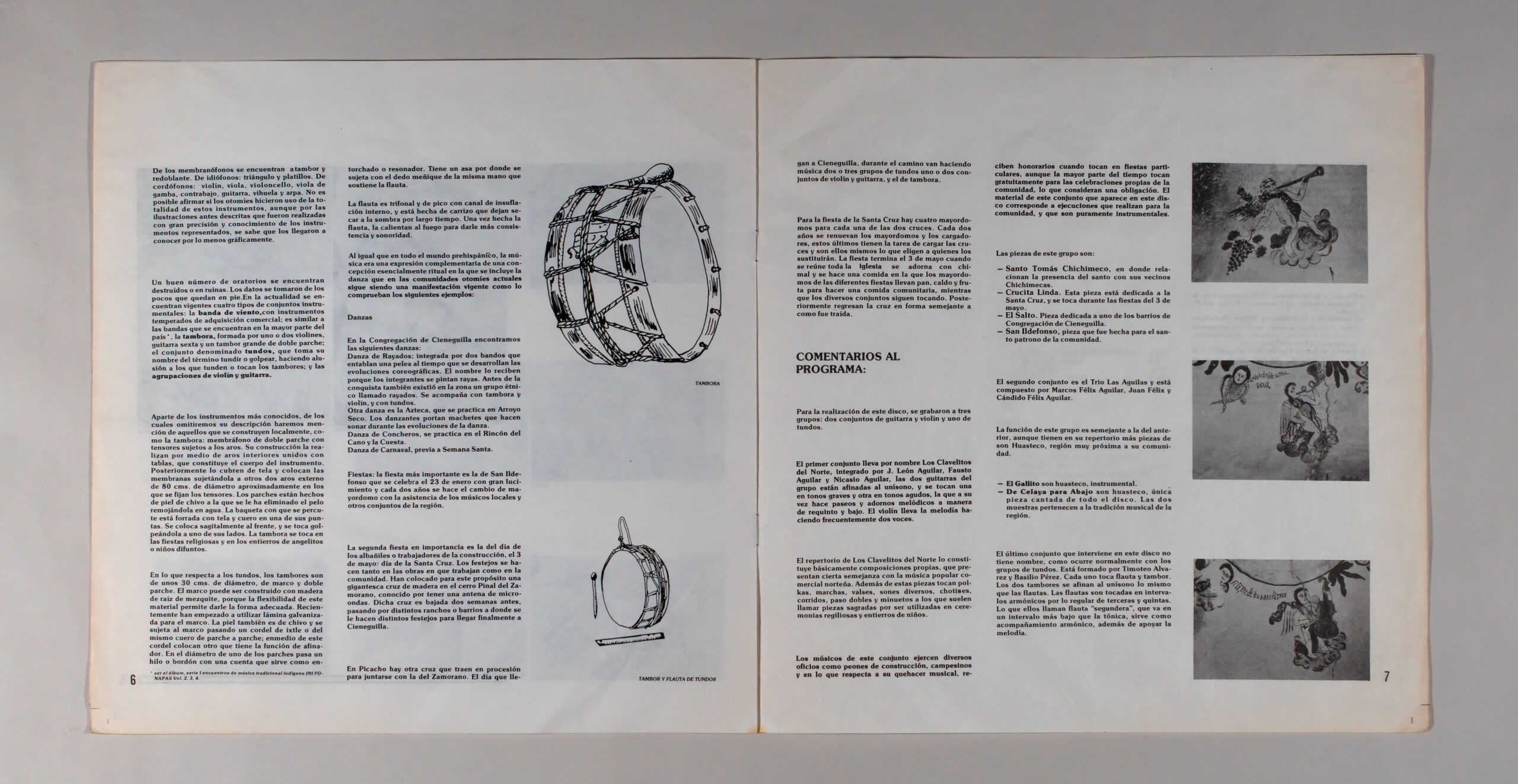

A good number of oratories are destroyed or in ruins. The data was taken from the few that remain standing. Currently, four types of instrumental ensembles are in force: the wind band, with commercially available tempered instruments; is similar to the bands found in most of the country”, the tambora, made up of one or two violins, a sixth guitar and a large double-headed drum; the group called tundos, which takes its name from the term tundir or hit , alluding to those who beat or play the drums, and the violin and guitar groups.

Apart from the best-known instruments, of which we will omit their description, we will mention those that are built locally, such as the tambora: a double-headed membranophone with tensioners attached to the sides. Its construction is carried out by means of internal rings joined with tables, which constitutes the body of the instrument. Subsequently, they cover it with cloth and place the membranes, holding it to two other 80 cm external rings. of diameter approximately in which the tensioners are fixed. The heads are made from goatskin from which the hair has been removed by soaking in water. The drumstick with which it is struck is lined with cloth and leather at one end. It is placed sagittally in front, and is played by hitting it on one of its sides. The tambora is played at religious festivals and at the burials of deceased angels or children.

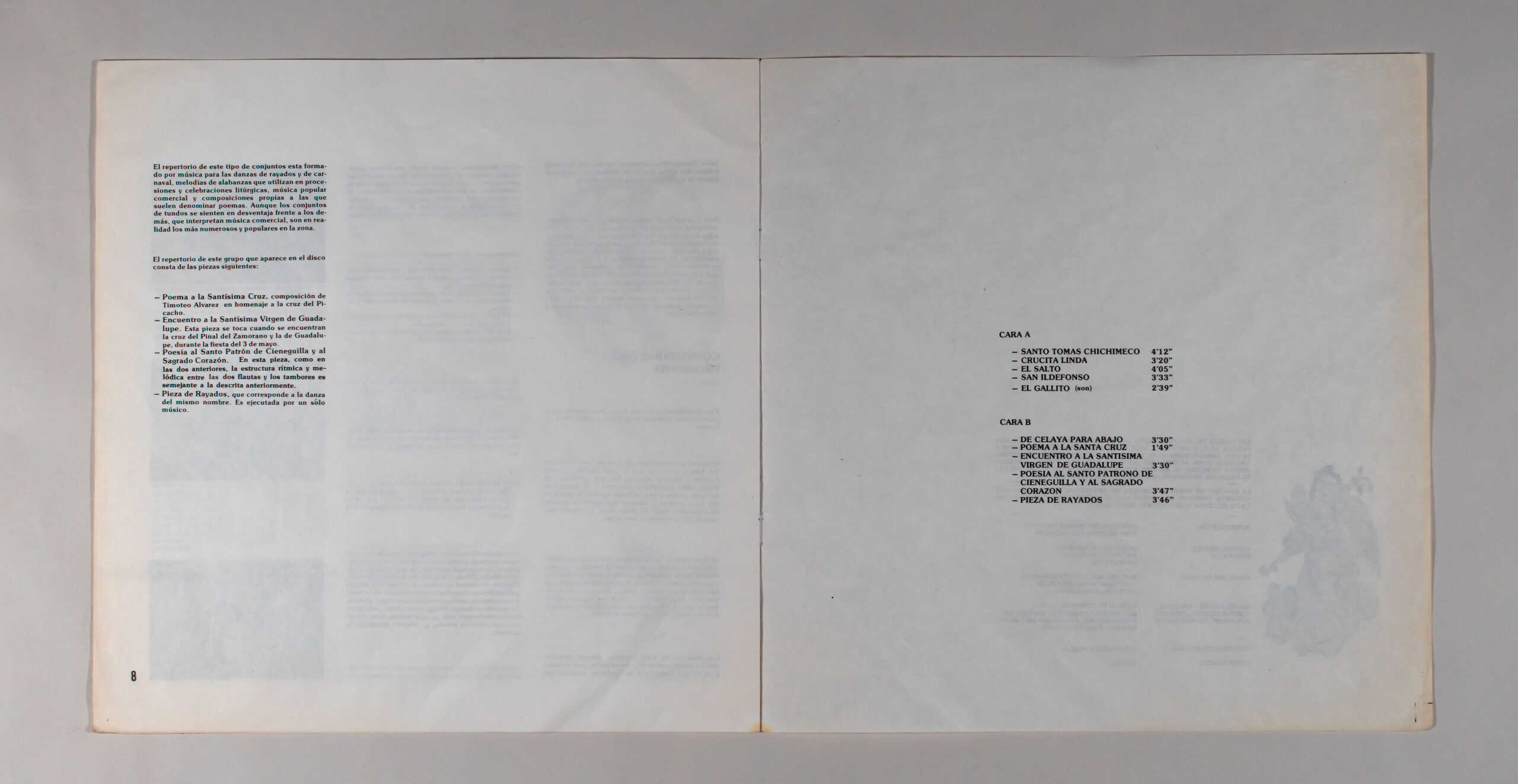

Regarding the tundos, the drums are about 30 cm in diameter, with a frame and a double head. The frame can be built with mesquite root wood, because the flexibility of this material allows it to be given the appropriate shape. They have recently started using galvanized sheet metal for the frame. The skin is also goat skin and is attached to the frame by passing an ixtle cord or the same leather from patch to patch; In the middle of this string they place another one that has the function of a tuner. In the diameter of one of the patches, a thread or a string passes with a bead that serves as a wound or resonator. It has a handle where it is held with the little finger of the same hand that holds the flute.

* see the album, series I meetings of traditional indigenous music INI FONAPAS Vol. 2, 3, 4.

The flute is triphonal and peaked with an internal insufflation channel, and is made of reed that is left to dry in the shade for a long time. Once the flute is made, it is heated over a fire to give it more consistency and sound.

As in the entire pre-Hispanic world, music was a complementary expression of an essentially ritual conception that included dance, which in today’s Otomi communities continues to be a current manifestation, as the following examples prove:

Dances

In the Congregation of Cieneguilla we find the following dances:

Rayados Dance; made up of two sides that engage in a fight while the choreographic evolutions are developed. The name is received because the members paint stripes. Before the conquest, an ethnic group called Rayados also existed in the area. It is accompanied with tambora and violin, and with tundos.

Another dance is the Azteca, which is practiced in Arroyo Seco. The dancers carry machetes that they make sound during the evolutions of the dance.

Danza de Concheros, is practiced in Rincón del Cano and La Cuesta.

Carnival dance, prior to Easter.

Festivals: the most important festival is that of San Ildefonso which is celebrated on January 23 with great brilliance and every two years the butler is changed with the assistance of local musicians and other groups from the region.

The second most important festival is the day of the masons or construction workers, on May 3: the day of the Holy Cross. The festivities are held both in the works where they work and in the community. They have placed for this purpose a gigantic wooden cross on the Pinal del Zamorano hill, known for having a microwave antenna. Said cross is lowered two weeks before, passing through different ranches or neighborhoods where different festivities are held to finally reach Cieneguilla.

In Picacho there is another cross that is brought in procession to join the Zamorano cross. On the day they arrive in Cieneguilla, along the way two or three groups of tundos make music, one or two violin and guitar ensembles; and the drum one.

For the feast of the Holy Cross there are four mayordomos for each of the two crosses. Every two years the mayordomos and porters are renewed, the latter have the task of carrying the crosses and they themselves choose who will replace them. The festival ends on May 3 when the entire church gathers, decorates itself with chimal and a meal is made in which the mayordomos of the different festivals bring bread, broth and fruit to make a communal meal, while the various groups continue to play. . Later they return the cross in a similar way to how it was brought.

COMMENTS TO THE PROGRAM:

For the realization of this album, three groups were recorded: two guitar and violin ensembles and one of tundos.

The first group is called Los Clavelitos del Norte, made up of J. León Aguilar, Fausto Aguilar and Nicasio Aguilar, the two guitars of the group are tuned in unison, and one is played in low tones and the other in high tones, which at in turn he makes walks and melodic ornaments in the manner of requinto and bass. The violin carries the melody frequently making two voices.

The repertoire of Los Clavelitos del Norte is basically made up of their own compositions, which present a certain resemblance to popular commercial northern music. In addition to these pieces they play polkas, marches, waltzes, various sones, chotises. corridos, pasodobles and minuets which are often called sacred pieces for being used in religious ceremonies and children’s burials.

The musicians of this ensemble work in various trades such as construction laborers, peasants, and in regards to their musical work, they receive fees when they play at private parties, although most of the time they play for free for the community’s own celebrations, which consider an obligation. The material from this group that appears on this album corresponds to performances they perform for the community, and which are purely instrumental.

The pieces in this group are:

– Santo Tomas Chichimeco, where they relate the presence of the saint with their Chichimecas neighbors.

– Cute little cross. This piece is dedicated to the Holy Cross, and is played during the festivities on May 3.

– The jump. Piece dedicated to one of the neighborhoods of Congregación de Cieneguilla.

– San Ildefonso, a piece that was made for the patron saint of the community.

The second group is the Trío Las Águilas and is made up of Marcos Félix Aguilar, Juan Félix and Cándido Félix Aguilar.

The function of this group is similar to that of the previous one, although they have in their repertoire more pieces from son Huasteco, a region very close to their community.

– The little rooster huasteco son, instrumental.

– From Celaya to Down they are Huasteco, the only piece sung on the entire album. The two samples belong to the musical tradition of the region.

The last ensemble that appears on this disc has no name, as is the normal case with groups of tundos. It is made up of Timoteo Alvarez and Basilio Pérez. Each plays flute and drum. The two drums are tuned in unison, the same as the flutes. The flutes are played in harmonic intervals, usually in thirds and fifths. What they call a “second” flute, which goes in an interval lower than the tonic, serves as a harmonic accompaniment, as well as supporting the melody.

The repertoire of this type of ensembles is made up of music for striped and carnival dances, praise melodies used in processions and liturgical celebrations, commercial popular music and their own compositions which they usually call poems. Although the tundos ensembles feel at a disadvantage compared to the others, which play commercial music, they are actually the most numerous and popular in the area.

The repertoire of this group that appears on the album consists of the following pieces:

– Poem to the Holy Cross, composition by Timoteo Alvarez in homage to the Picacho cross.

– Meeting with the Blessed Virgin of Guadalupe. This piece is played when the Pinal del Zamorano cross and the Guadalupe cross meet, during the 3rd of May festival.

– Poetry to the Patron Saint of Cieneguilla and the Sacred Heart. In this piece, as in the two previous ones, the rhythmic and melodic structure between the two flutes and the drums is similar to that described above.

– Piece of Rayados, which corresponds to the dance of the same name. It is executed by a single musician.

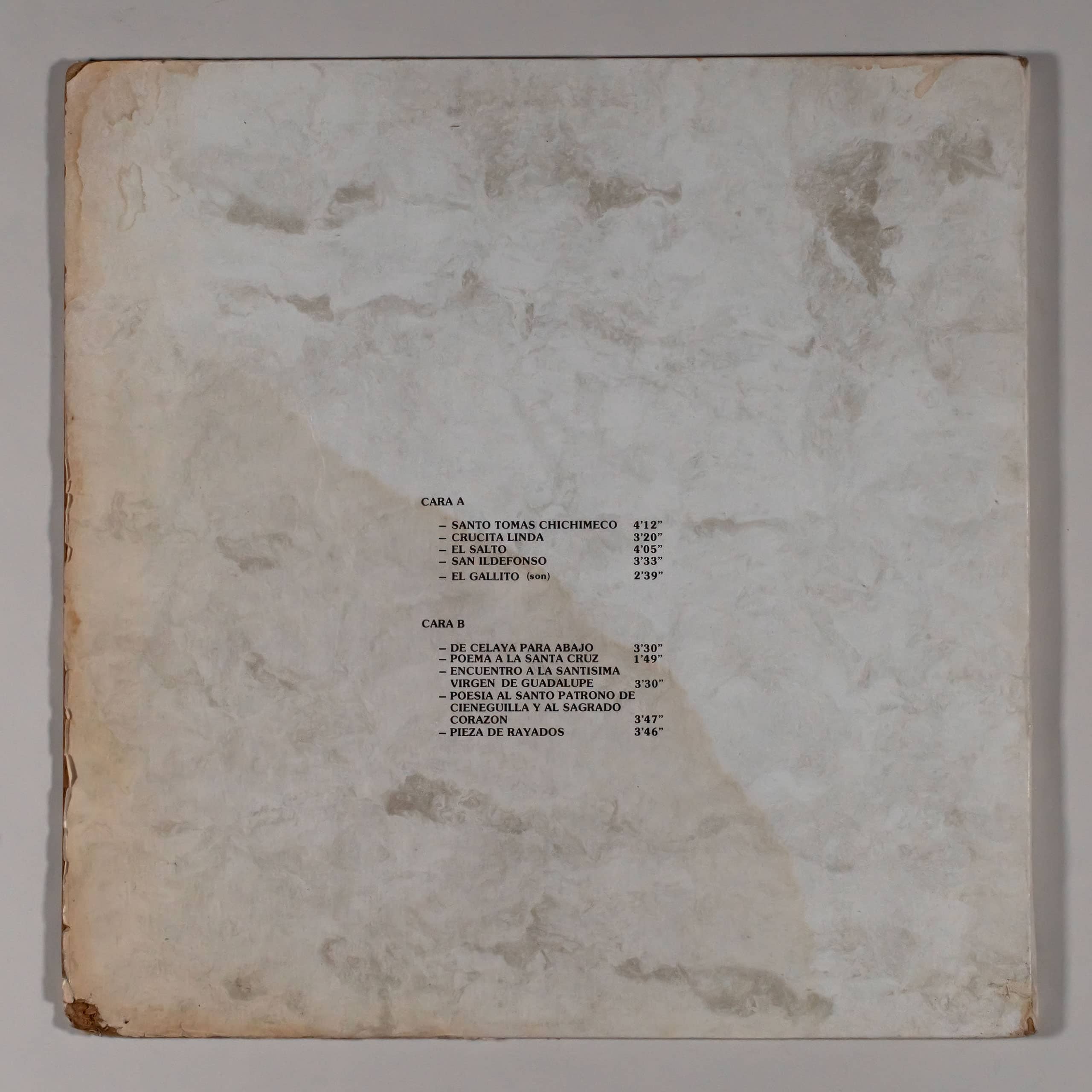

FACE A

– SANTO TOMAS CHICHIMECO 4:12

– CUTE CROSS 3:20

– THE JUMP 4:05

– SAN ILDEFONSO 3:33

– THE LITTLE ROOSTER (son) 2:39

FACE B

– FROM CELAYA DOWNWARD 3:30

– POEM TO THE HOLY CROSS 1:49

– MEETING THE HOLY VIRGIN OF GUADALUPE 3:30

– POETRY TO THE PATRON SAINT OF CIENEGUILLA AND THE SACRED HEART 3:47

– PIECE OF STRIPES 3:46

THE RESEARCH TASKS AND COLLECTION OF MATERIALS THAT MADE THE REALIZATION OF THIS ALBUM POSSIBLE WERE ACHIEVED THANKS TO MRS. CARMEN ROMANO DE LOPEZ PORTILLO, PRESIDENT OF THE NATIONAL FUND FOR SOCIAL ACTIVITIES (FONAPAS), FOR THE FINANCING GRANTED TO THE AUDIOVISUAL ETHNOGRAPHIC ARCHIVE OF THE NATIONAL INDIGENIST INSTITUTE WITHIN THE OLLIN YOLIZTLI PROGRAM.

THE EDITION OF THESE CULTURAL REVALUATION MATERIALS WAS ALSO COVERED WITH THE GENEROUS FINANCIAL CONTRIBUTION OF VARIOUS TRADE UNIONS.

ALFRED ELIAS

DIRECTOR OF THE NATIONAL FUND FOR SOCIAL ACTIVITIES

IGNACIO OVALLE FERNANDEZ

GENERAL DIRECTOR OF THE NATIONAL INDIGENIST INSTITUTE

JOHN CARLOS COLIN

HEAD OF THE AUDIOVISUAL ETHNOGRAPHIC ARCHIVE OF THE NATIONAL INDIGENIST INSTITUTE

ANGEL AGUSTIN PIMENTEL

JESUS HERRERA PIMENTEL

ALEJANDRO MENDEZ ROJAS

ETHNOMUSICOLOGY UNIT IN CHARGE OF THE RESEARCH WORK, FIELD RECORDING, EDITING, AND COORDINATION.

JOSE MANUEL PAINTED

WRITING AND STYLE

DAVID MENDEZ

DESIGN

Tracklist:

THE MUSIC OF AN OTOMI COMMUNITY

SIDE 1

- A1 SANTO TOMAS CHICHIMECO 4:12

Performer(s): - A2 CUTE CROSS 3:20

Performer(s): - A3 THE JUMP 4:05

Performer(s): - A4 SAN ILDEFONSO 3:33

Performer(s): - A5 THE LITTLE ROOSTER (sound) 2:39

Performer(s):

SIDE 2

- B1 FROM CELAYA DOWN 3:30

Performer(s): - B2 POEM TO THE HOLY CROSS 1:49

Performer(s): - B3 MEETING THE HOLY VIRGIN OF GUADALUPE 3:30

Performer(s): - B4 POETRY TO THE PATRON SAINT OF CIENEGUILLA AND THE SACRED HEART 3:47

Performer(s): - B5 SCRATCHED PIECE 3:46

Performer(s):

Credits:

Alfred Elias

Director Of The National Fund For Social Activities

Ignacio Ovalle Fernandez

General Director Of The National Indigenist Institute

John Carlos Colin

Head Of The Audiovisual Ethnographic Archive Of The National Indigenist Institute

Angel Agustin Pimentel

Jesus Herrera Pimentel

Alejandro Mendez Rojas

Ethnomusicology Unit In Charge Of The Research Work, Field Recording, Editing, And Coordination.

Jose Manuel Painted

Writing And Style

David Mendez

Design

Notes:

The little roosterthe research tasks and collection of materials that made the realization of this album possible were achieved thanks to mrs. Carmen romano de lopez portillo, president of the national fund for social activities (fonapas), for the financing granted to the audiovisual ethnographic archive of the national indigenist institute within the ollin yoliztli program.

The edition of these cultural revaluation materials was also covered with the generous financial contribution of various trade unions.