Description

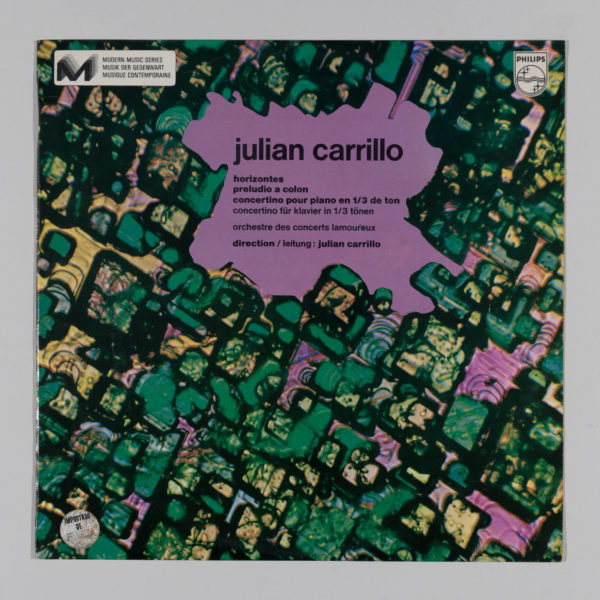

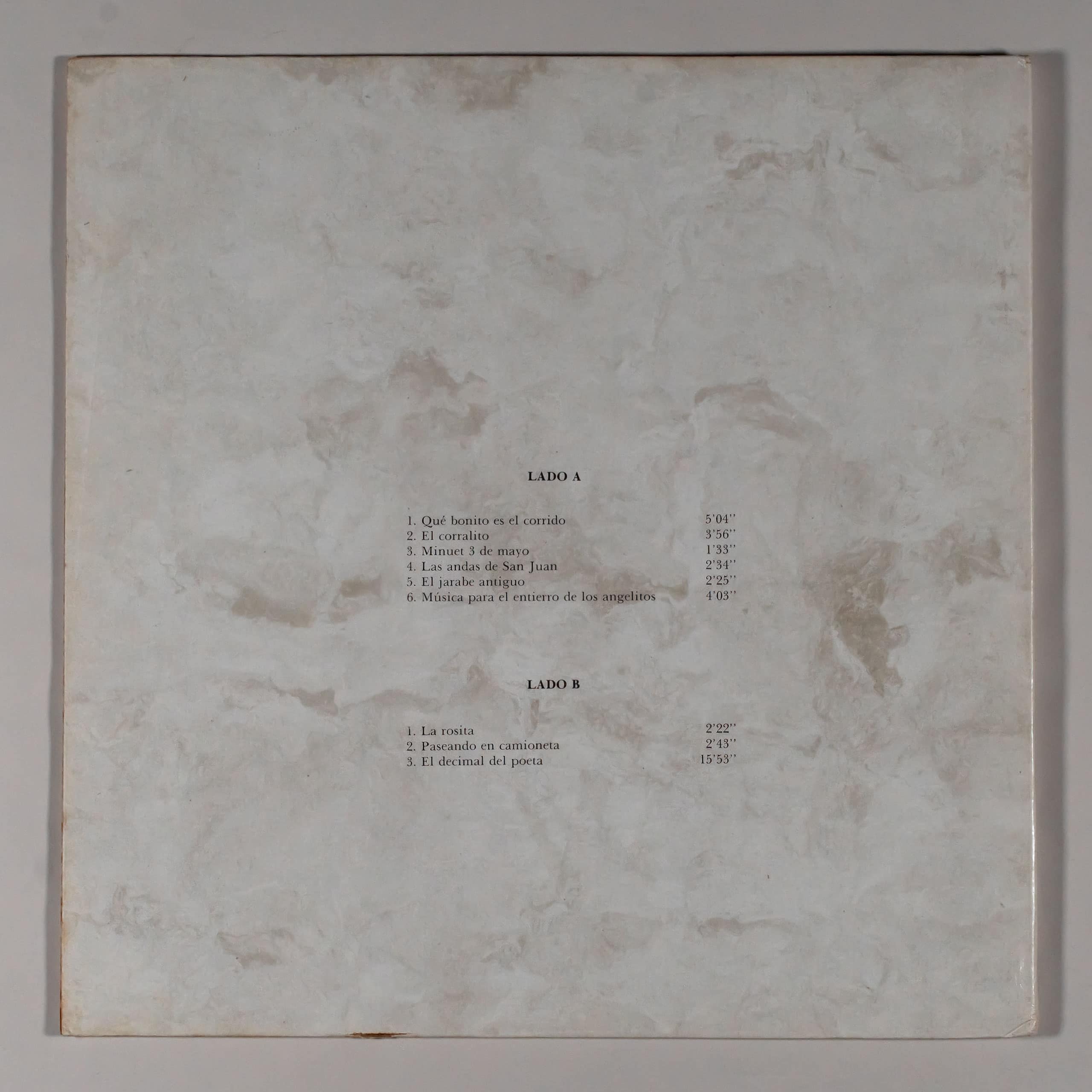

MUSIC AMONG THE CHICHIMECAS

SERIES IV.- MUSIC IN INDIGENOUS COMMUNITIES VOLUME I.-

AUDIOVISUAL ETHNOGRAPHIC ARCHIVE OF THE NATIONAL INDIGENIST INSTITUTE

FONAPAS – INI

INTRODUCTION

BACKGROUND

Just as the Aztecs mythically place the seat of their origin in a place called Aztlán, the Chichimecas remote the space of their origin to the country of Amaqueme, always to the north of the Valley of Mexico, within a geography whose limits are already impossible to establish.

According to one version, the word “Chichimeca” comes from “Chichiliztli”, the act of sucking or suckling. Torquemada exposes it in the following way: “They took their name from Chichimecas, these people (who named themselves that way), from the effect, means their name (sic); because Chichimécatl, both means the act of suckling or suckling; and Chichinaliztli is the act of sucking or sucking, and that is what the woman’s breast and teat are called; and that of any other animal Chichihualli; and because these people, in their beginnings, ate the meat of the animals they killed, raw and They sucked blood, like a sucker, that’s why they were called Chichimecas, which means suckers or suckers”.

Fray Agustín de Betancourt (1620-1700) derives its name from the word “Chichimeque”, which would come to mean “lineage of dogs”, as their enemies pejoratively referred to them. It has been said, however, that if this were the meaning of the word, there would be no reason for those so designated to boast, as they did, of their Chichimec condition. In this regard, an explanation could be found in the Mexica tradition corresponding to Xólotl, (Itzcuintli, dog), Quetzalcóatl’s twin deity whose long tail ended in an open hand. Xólotl, the name that one of the mythical Chichimeca leaders also bears, is, in the Mexica tradition, the furtive god who stole, from the kingdom of the dead, a bone that, when broken, gave rise to humanity. According to some writers, the explanation could seem plausible.

The Chichimecas settled in the lands of the Valley of Mexico at the end of the Toltec civilization, with the representatives of whose decadence they came into contact. However, their first significant inter-ethnic relationships occurred with the Acolhua groups, from which they learned to sacrifice “herbs and other things of this nature” to the sun and moon, according to Torquemada. And according to this same author, it is from his dealings with the Aztecs that they begin in the ritual practice of human sacrifices.

This moment is important for ethnomusicology because it marks the record of the first formal manifestations of music and dance among the Chichimecas, without this meaning that before, as hunters and fruit gatherers, they would not have produced it in the same way. rudimentary that is indicated for the Paleolithic: use of instruments such as the bule (rattles), hoof strings, bone flutes, buzzing sticks, scrapers, etc.

In the specific case of child sacrifices, Torquemada establishes through his sources that: “They took these children to the place of sacrifice, very composed of rich and precious attire, placed on litters or litters, richly decorated with feathers and flowers, which the priests and ministers carried on their shoulders, and they went singing, playing and dancing before them, and in this way they proceeded to the place where they were to be sacrificed”. Music and dance, as can be seen, fulfilled a ritual function within the lavish ceremonial sacrifice.

The original Chichimeca group dispersed, integrating and merging with the Acolhuas, Aztecs, and Texcocans, essentially due to their transition from a nomadic state to that of farmers and by virtue of human settlements. An important minority group, however, did not accept the new status and remained rebellious and in a state of war, allying with the Otomi. This situation prevailed until the colony.

To end the conflict that the Chichimecas harassed the Spanish caravans that transported gold and silver from the Zacatecas mines, and also with the purpose of using their labor, Viceroy Luis de Velasco the Second, determined in 1552 the foundation of San Luis de la Paz, Guanajuato, populating it with Otomi; In its outskirts, the Chichimeca mission was established so that the former warriors could live there at the time of their surrender, since scattered groups of indigenous combatants survived. The measure produced, gradually, the result of pacification that it was looking for, from the very moment that it was erected halfway between Mexico and Zacatecas.

Enrique Rivas Paniagua (“El Día” newspaper, October 3, 1980), maintains that “The details of the founding of San Luis de la Paz are worthy examples of the colonizing policy of the mid-16th century, particularly from the period of Viceroy Velasco “. And he adds: “The king’s representative granted them grants of 100 square kilometers, gave them minor tools for working the land for a couple of years, and exempted them from paying taxes within a term of 16 years (more than the time required). His Majesty’s will, he added.) And to avoid harmful interference from his countrymen, one of the clauses specified that “the Spaniards will not be given land or cattle ranches”, except those that the town has for their safety and accompaniment. Finally, he gave them permission to name their own governors, mayors, and aldermen.”

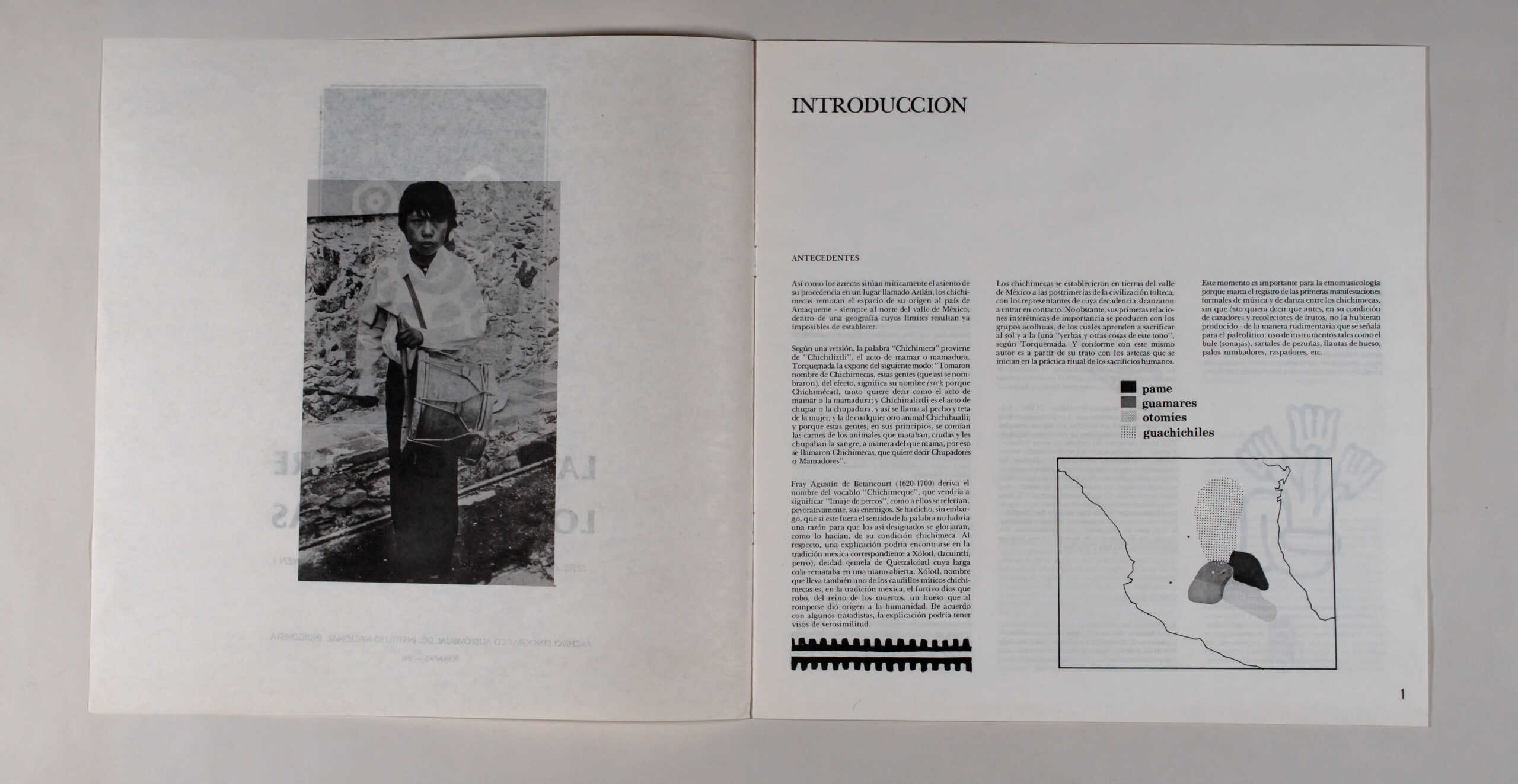

LOCATION

Currently, the Chichimecas settle in the community called Misión de Chichimecas, located two kilometers east of the city of San Luis de la Paz. Chichimecas Mission is inhabited by about 1,543 people, mostly bilingual.

The climate of the place is temperate cold in winter and hot dry in summer, with sudden drops in temperature between November and February, registering intense heat between April and May. The main flora of the region is made up of cacti, while the fauna registers different kinds of rodents, as well as opossums, coyotes, skunks and various species of birds, reptiles and insects.

ECONOMIC ASPECTS

In general, the Chichimecas share communal activities with wage labor on neighboring private properties. They harvest beans, chili, nopales, garlic, etc. They work the smaller livestock and hardly the larger ones. Occasionally they work as masonry laborers, and the women as servants of the mestizos and as collectors and sellers of fruits and wild plants.

MUSICAL LIFE

It is relatively easy to follow the history and evolution of music in societies that, after sedentarization, reached more or less notable levels of development. Indeed, the stratification of society brings with it privileges and leisure, and in this way music becomes a specialized activity to which only holders of public power have access, whose structure provides elements of systematization and analysis to the scholars. Difficult musical of those groups that, as is the case of the Chichimecas, instead establish the guidelines of life, they even faced the need to defend the minimum hunting and gathering plots necessary for their subsistence.

At the time of the arrival of the Spaniards, the Chichimeca historical group that we follow maintains an attitude of rebellion and precarious support in its scheme of hunters and gatherers. Thus, to the incipient musical culture, properly Paleolithic in which they manifested themselves, they came to integrate songs, ceremonies and instruments from the cultures of the Valley of Mexico, with which they were in a permanent state of struggle.

The Spanish music that reaches the ears of the Chichimecas for the first time is, of course, that of war. In this regard, the account of Fray Antonio de Belmoy is illustrative: “I was fighting with them, sounding drums and bugles; we were fighting for twenty-four hours, until I defeated them, and I captured 350 Chichimecos”.

As the penetration of the new culture took shape, other instruments became present in the life of the Chichimecas, coming from liturgical and populous music.

Already by 1634 there is news of Chichimeca singers within the ecclesiastical musical structure. That year, on the occasion of a request for land to stay for livestock filed by Captain Goni de Peralta, Juan Jusephe, “the principal and natural Indian, Chichimeco singer of the church” appeared as a witness in the proceedings, according to the notary public. Francisco Núñez, from San Luis de la Paz.

Likewise, it can be verified by the frescoes painted in the Otomí hermitages of Tierra Blanca, Guanajuato, all the instruments that they knew, not wanting to say that they played them. In the paintings, angel musicians can be seen with bassoon, drum flute, timpani, triangle, cymbals, vihuelas, basses, viola da gamba, violin, shawm, fife, snare drum, harp, trumpet, sackbut, bugle, as well as musical notation.

BROTHERHOODS AND STEWARDSHIPS

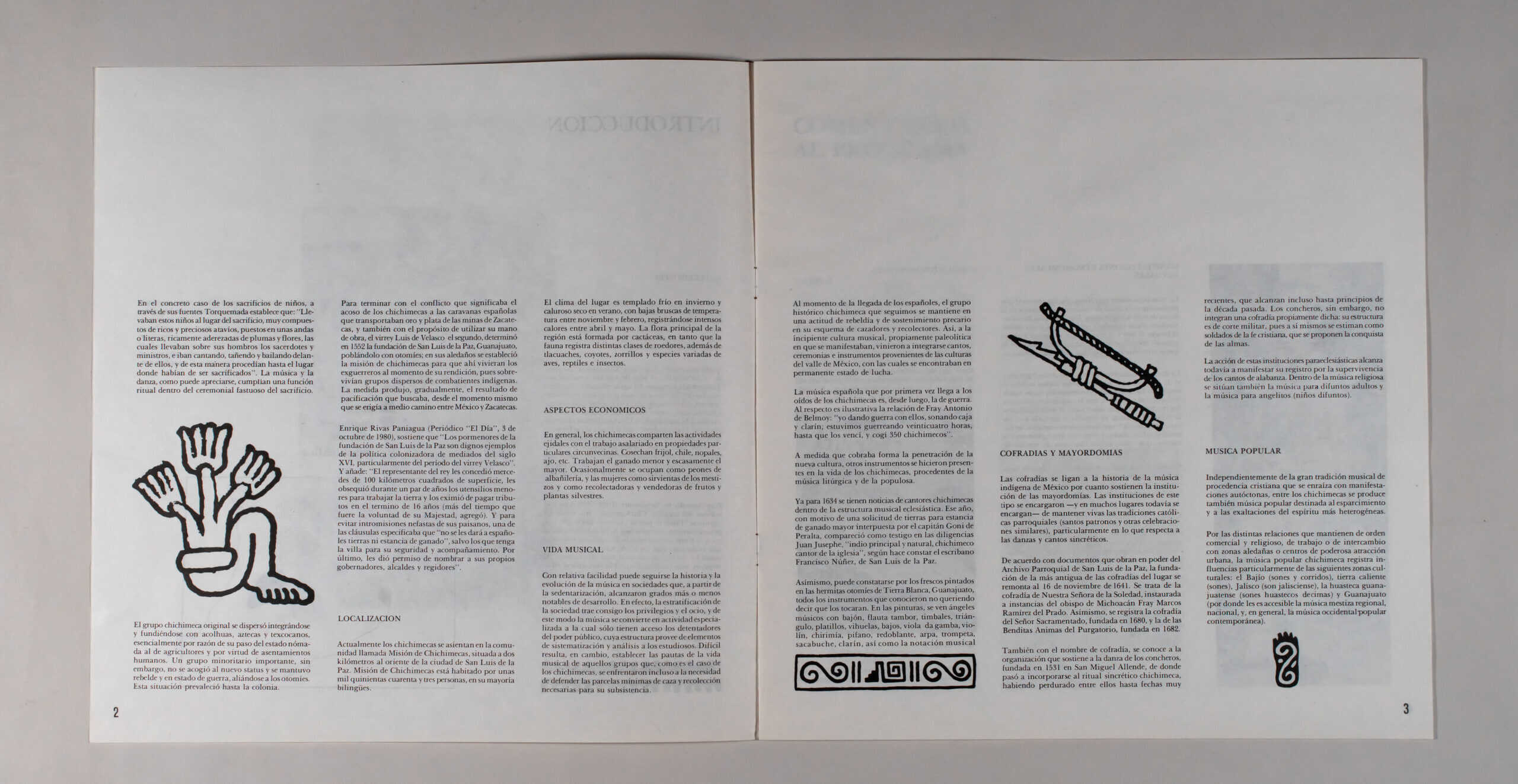

The brotherhoods are linked to the history of indigenous music in Mexico because they support the institution of stewardships. Institutions of this type were in charge – and in many places still are in charge – of keeping alive the parish Catholic traditions (patron saints and other similar celebrations), particularly with regard to syncretic dances and songs.

According to documents in the possession of the Parish Archive of San Luis de la Paz, the foundation of the oldest of the brotherhoods of the place dates back to November 16, 1641. It is the brotherhood of Nuestra Señora de la Soledad, Established at the request of the Bishop of Michoacán Fray Marcos Ramírez del Prado. Likewise, the brotherhood of Señor Sacramentado, founded in 1680, and that of the Blessed Souls of Purgatory, founded in 1682, are recorded.

Also known as the brotherhood is the organization that supports the dance of the concheros, founded in 1531 in San Miguel Allende, from where it became incorporated into the syncretic Chichimeca ritual, having lasted among them until very recent dates, reaching even until the beginning of the last decade. The concheros, however, are not part of a brotherhood as such: their structure is of a military nature, since they consider themselves as soldiers of the Christian faith, who propose the conquest of souls.

The action of these para-ecclesiastical institutions still manages to manifest its record through the survival of songs of praise. Within religious music there are also music for deceased adults and music for little angels (deceased children).

POPULAR MUSIC

Regardless of the great musical tradition of Christian origin that is rooted in autochthonous manifestations, popular music is also produced among the Chichimecas for recreation and the most heterogeneous exaltations of the spirit.

Due to the different relationships that they maintain of a commercial and religious order, of work or exchange with neighboring areas or centers of powerful urban attraction, Chichimeca popular music registers influences particularly from the following cultural zones: the Bajío (sones and corridos), tierra caliente (sones), Jalisco (Jalisciense son), the Guanajuato huasteca (tenth huasteco sones) and Guanajuato (where regional and national mestizo music, and, in general, contemporary popular western music is accessible to them).

CURRENT ETHNOMUSICAL MANIFESTATIONS

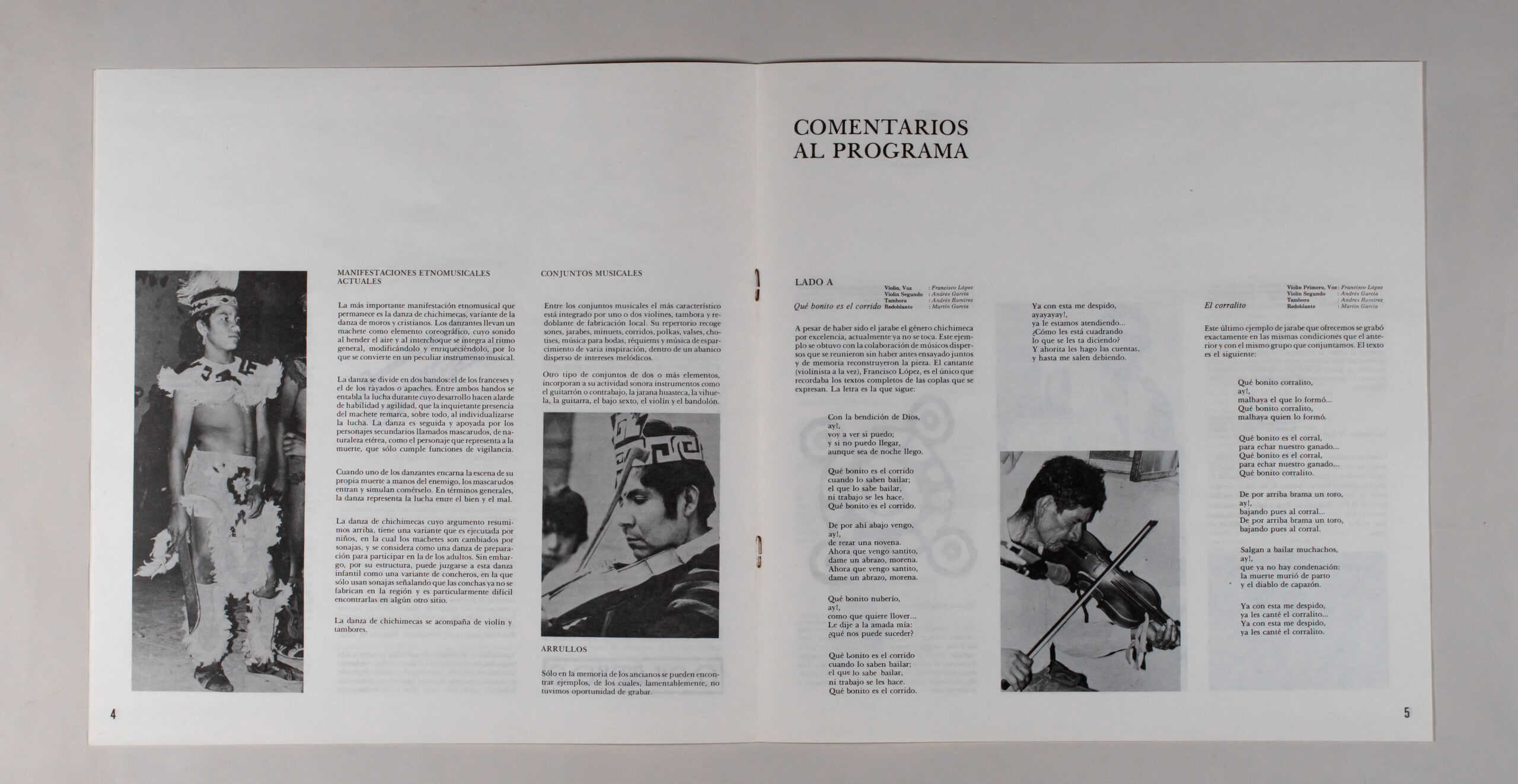

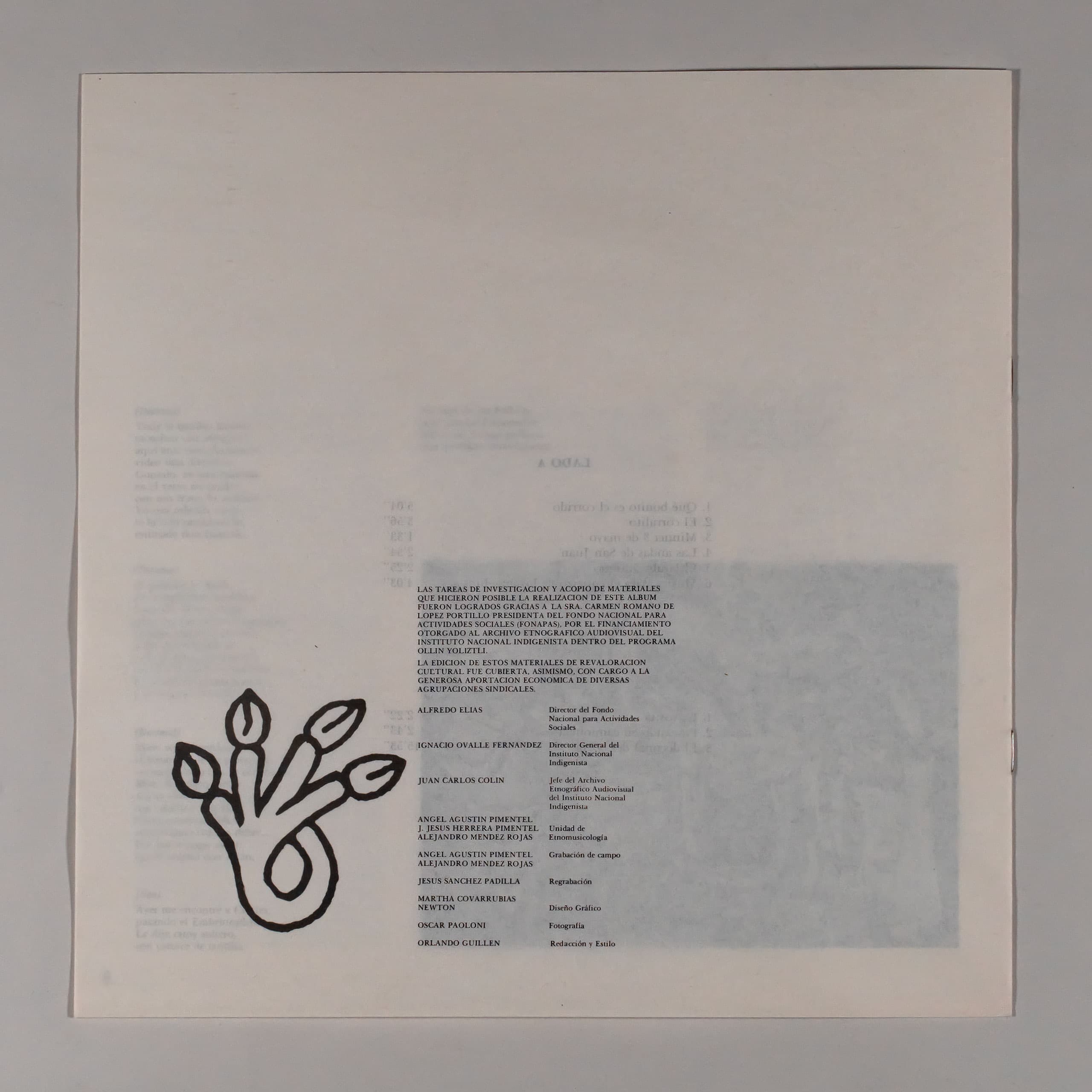

The most important ethnomusical manifestation that remains is the Chichimeca dance, a variant of the Moors and Christians dance. The dancers carry a machete as a choreographic element, whose sound when splitting the air and the clash is integrated into the general rhythm, modifying and enriching it, thus becoming a peculiar musical instrument.

The dance is divided into two groups: that of the French and that of the striped or Apaches. Both sides engage in a fight during which they show off their skill and agility, which the disturbing presence of the machete highlights, above all, by individualizing the fight. The dance is followed and supported by secondary characters called mascarudos, of an ethereal nature, like the character that represents death, who only performs surveillance functions.

When one of the dancers enacts the scene of his own death at the hands of the enemy, the masked men enter and pretend to eat him. Generally speaking, the dance represents the fight between good and evil.

The Chichimeca dance whose argument we summarized above, has a variant that is performed by children, in which the machetes are exchanged for rattles, and is considered a preparation dance to participate in that of adults. However, due to its structure, this children’s dance can be judged as a variant of shell shells, in which they only use rattles, indicating that the shells are no longer made in the region and it is particularly difficult to find them elsewhere.

The chichimecas dance is accompanied by violin and drums.

MUSICAL ENSEMBLES

Among the musical ensembles, the most characteristic is made up of one or two violins, a tambora and a snare drum made locally. His repertoire includes sones, syrups, minuets, corridos, polkas, waltzes, chotises, music for weddings, requiems and entertainment music of various inspirations, within a dispersed range of melodic interests.

Other types of ensembles of two or more elements incorporate instruments such as the guitarrón or double bass, the Huasteca jarana, the vihuela, the guitar, the bajo sexto, the violin and the bandolón into their sound activity.

COOS

Examples of which, unfortunately, we did not have the opportunity to record, can only be found in the memory of the elderly.

COMMENTS TO THE PROGRAM

SIDE A

How beautiful is the corrido

Violin, voice : Francisco López

Second violin : Andrés Garcia

Drum : Andrés Ramirez

Snare drum : Martín Garcia

Despite the fact that syrup was the Chichimeca genre par excellence, it is no longer played today. This example was obtained with the collaboration of scattered musicians who met without having previously rehearsed together and reconstructed the piece from memory. The singer (violinist at the same time), Francisco López, is the only one who remembered the complete texts of the couplets that are expressed. The letter is as follows:

With God’s blessing,

Oh!,

I’ll see if I can;

And if I can’t get there

Even if it’s night I arrive.

How beautiful is the corrido

when they know how to dance it;

the one who knows how to dance,

nor work is done to them.

How beautiful is the corrido.

I come from down there

Oh!,

to pray a novena

Now that I come holy,

give me a hug, brunette.

What a beautiful cloud

Oh!,

like it wants to rain…

I told my beloved:

what can happen to us?

How beautiful is the corrido

when they know how to dance it;

the one who knows how to dance,

nor work is done to them.

How beautiful is the corrido.

With this I say goodbye,

Ay, ay, ay, ay!,

We are already serving you…

How is it stacking up for them?

what are they saying?

And now I do the accounts,

and they even owe me.

The playpen

First violin, voice : Francisco López

Second violin : Andrés Garcia

Drum : Andrés Ramirez

Snare drum : Martin Garcia

This last example of syrup that we offer was recorded in exactly the same conditions as the previous one and with the same group that we put together. The text is as follows:

What a pretty playpen

Oh!,

curse the one who formed it…

What a pretty playpen

damn who formed it.

How beautiful is the corral,

to cast our cattle…

How beautiful is the corral,

to cast our cattle…

What a nice playpen.

From above a bull bellows,

Oh!,

going down to the corral…

From above a bull bellows,

going down to the corral.

Go out dancing guys

Oh!,

that there is no condemnation anymore:

death died in childbirth

and the capon devil.

With this I say goodbye,

I already sang the corralito…

With this I say goodbye,

I already sang the corralito.

Minuet May 3

First violin : Manuel Martinez

Second violin : Aquilino Mendoza

Snare drum : Cristóbal Ramirez

Drum : Jesús Ramirez

This piece is made up of parts A and B, which alternate. The melody is sustained by two violins in parallel thirds, while the harmony is replaced and the rhythm is provided by the tambora and the snare drum. In the first part, the tambora accentuates the bars; in the second, when hit with a ring, they become more sweet. It is music that is interpreted in religious festivities.

The litter of San Juan

First violin : Manuel Martínez

Second violin : Aquilino Mendoza

Snare drum : Cristóbal Ramírez

Drum : Jesús Ramirez

Like the previous one, this piece constitutes a religious variant of the minuet. When used by Apache and French dancers, it is useful to accompany their rhythmic movement within an itinerary that starts from Misión de Chichimecas and ends in San Luis de la Paz. When the walk of the icon of San Juan is carried out, it returns to collect religious utility. This event occurred in the early morning of June 24.

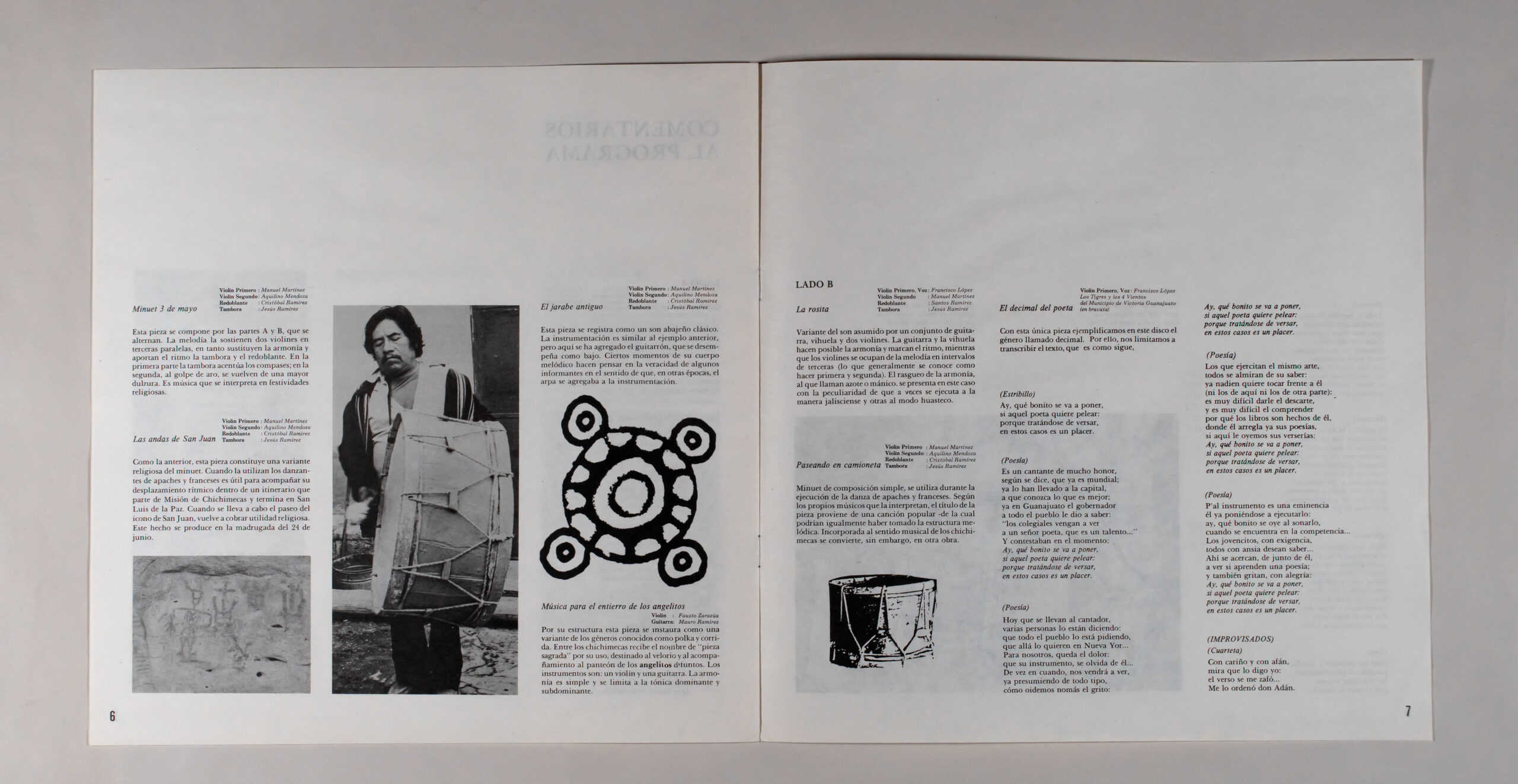

The ancient syrup

First violin : Manuel Martinez

Second violin : Aquilino Mendoza

Snare drum : Cristóbal Ramírez

Drum : Jesús Ramírez

This piece is recorded as a classic son abajeño. The instrumentation is similar to the previous example, but here the guitarrón has been added, which serves as a bass. Certain moments of his melodic body suggest the truth of some informants in the sense that, in other times, the harp was added to the instrumentation.

Music for the burial of angels

Violin : Fausto Zarazúa

Guitar : Mauro Ramírez

Due to its structure, this piece is established as a variant of the genres known as polka and corrida. Among the Chichimecas it is called a “sacred piece” because of its use, intended for wakes and accompaniment to the pantheon of the deceased angels. The instruments are: a violin and a guitar. The harmony is simple and limited to the dominant and subdominant tonic.

SIDE B

The little rose

First violin, voice : Francisco López

Second violin : Manuel Martinez

Snare drum : Santos Ramírez

Drum : Jesús Ramírez

Variant of the son assumed by a group of guitar, vihuela and two violins. The guitar and vihuela provide harmony and set the rhythm, while the violins handle the melody in intervals of thirds (generally known as doing first and second). The strumming of harmony, which is called whipping or manic, is presented in this case with the peculiarity that it is sometimes performed in the Jalisco manner and other times in the Huastec manner.

Riding in a van

First violin : Manuel Martinez

Second violin : Aquilino Mendoza

Snare drum : Cristóbal Ramírez

Drum : Jesús Ramirez

Minuet of simple composition, it is used during the execution of the dance of Apaches and French. According to the musicians who perform it, the title of the piece comes from a popular song from which they could also have taken the melodic structure. Incorporated into the musical sense of the Chichimecas, however, it becomes another work.

The poet’s decimal

First violin, voice : Francisco López

Los Tigres y los 4 Vientos from Municipality of Victoria Guanajuato (in bravado)

With this unique piece we exemplify on this album the genre called decimal. Therefore, we limit ourselves to transcribing the text, which is as follows.

(Chorus)

Oh, how beautiful it’s going to be

if that poet wants to fight:

because when it comes to verse,

in these cases it is a pleasure.

(Poetry)

He is a singer of much honor,

it is said that he is already worldwide;

They have already taken him to the capital,

that he knows what is best;

already in Guanajuato the governor

He told all the people:

“the schoolboys come to see

to a gentleman poet, who is a talent…”

And they answered at the moment:

Oh, how beautiful it’s going to be

if that poet wants to fight:

because when it comes to verse,

in these cases it is a pleasure.

(Poetry)

Today they take the singer,

several people are saying it:

that all the people are asking for it,

that they want it there in New York…

For us, the pain remains:

that the instrument of him, he forgets about him …

From time to time, he will come to see us,

already boasting of all kinds,

how can we just hear the cry:

Oh, how beautiful it’s going to be

if that poet wants to fight:

because when it comes to verse,

in these cases it is a pleasure.

(Poetry)

Those who exercise the same art,

everyone admires the knowledge of him:

no one wants to play in front of him anymore

(neither from here nor from elsewhere):

it is very difficult to discard it,

and it is very difficult to understand

why books are made of it,

where he already arranges his poetry,

Here we hear his verses:

Oh, how beautiful it’s going to be

if that poet wants to fight:

because when it comes to verse,

in these cases it is a pleasure.

(Poetry)

P’al instrument is an eminence

he already starting to execute it:

oh, how beautiful it sounds when you sound it,

when he finds himself in the competition…

The youngsters, demandingly,

everyone eagerly wants to know…

There they approach, next to him,

Let’s see if they learn a poem;

and they also shout, with joy:

Oh, how beautiful it’s going to be

if that poet wants to fight:

because when it comes to verse,

in these cases it is a pleasure.

(IMPROVISED)

(quatrain)

With love and eagerly,

Look what I say:

the verse slipped away…

Don Adán ordered me to.

(Decimal)

The whole Montes family,

Listen carefully:

here before these horizons,

see a fun

Gonzalo: in this meeting,

in the verse I do not stop:

I finished it with my sentences.

I with good reason

I give you preference

Dear Don Gonzalo.

(Decimal)

The public said so

to fulfill a duty:

Gonzalo: I’ll let you know

that today that my chest gorgue

(although he sees me in a hurry,

so much so I clarify,

because so I was ordered):

I will leave with pleasure and content…

I give you applause

and the verse slipped away from me.

(Decimal)

Look: I’m going to finish

the verse that I have raised

– Complying with the order.

Look: I want to sing to you…

This is how it came to order,

lovingly and eagerly:

correct phrases will say,

fulfilling a duty…

That’s why I let you know:

Don Adán ordered me,

(Son)

Yesterday I met Cecilia,

passing the Embrincadero.

I told him I’m single

with fourteen family.

I came from the Fallitas,

I passed through the Bowers:

I came to see these chicks

that they were devastated.

I really like Esther

because she is a peasant woman:

to give me pleasure

and kitchen chores.

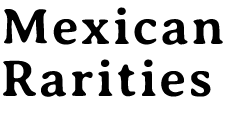

SIDE A

- How beautiful is the corrido 5’04”

- The playpen 3’56”

- Minuet May 3 1’33”

- The litter of San Juan 2’34”

- The old syrup 2’25”

- Music for the burial of the little angels 4’03”

SIDE B

- The pink ball 2’22”

- Riding in a truck 2’43”

- The poet’s decimal 15’53”

THE RESEARCH TASKS AND COLLECTION OF MATERIALS THAT MADE THE REALIZATION OF THIS ALBUM POSSIBLE WERE ACHIEVED THANKS TO MRS. CARMEN ROMANO DE LOPEZ PORTILLO PRESIDENT OF THE NATIONAL FUND FOR SOCIAL ACTIVITIES (FONAPAS), FOR THE FINANCING GRANTED TO THE AUDIOVISUAL ETHNOGRAPHIC ARCHIVE OF THE NATIONAL INDIGENOUS INSTITUTE WITHIN THE OLLIN YOLIZTLI PROGRAM.

THE EDITION OF THESE CULTURAL REVALUATION MATERIALS WAS ALSO COVERED WITH THE GENEROUS FINANCIAL CONTRIBUTION OF VARIOUS TRADE UNIONS.

ALFREDO ELIAS

Director of the National Fund for Social Activities

IGNACIO OVALLE FERNANDEZ

General Director of the National Indigenous Institute

JOHN CARLOS COLIN

Head of the Audiovisual Ethnographic Archive of the National Indigenous Institute

ANGEL AGUSTIN PIMENTEL

JESUS HERRERA PIMENTEL

ALEJANDRO MENDEZ ROJAS

Ethnomusicology Unit

ANGEL AGUSTIN PIMENTEL

ALEJANDRO MENDEZ ROJAS

Field recording

JESUS SANCHEZ PADILLA

Re-recording

MARTHA COVARRUBIAS NEWTON

Graphic design

OSCAR PAOLONI

Photography

ORLANDO GUILLEN

Writing and Style

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.