|

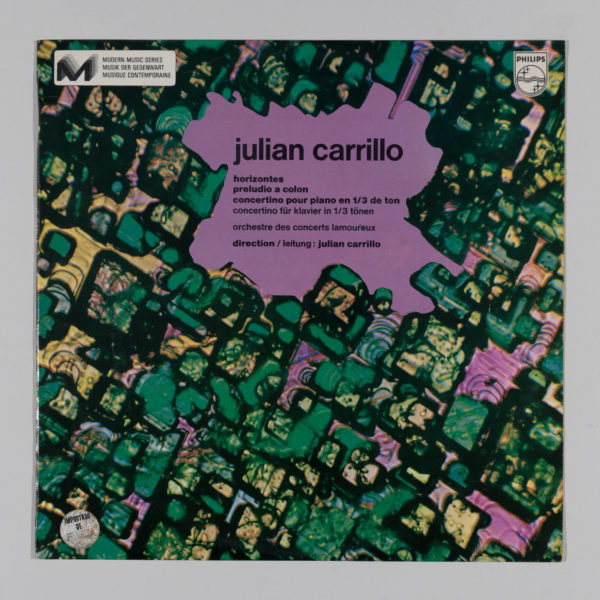

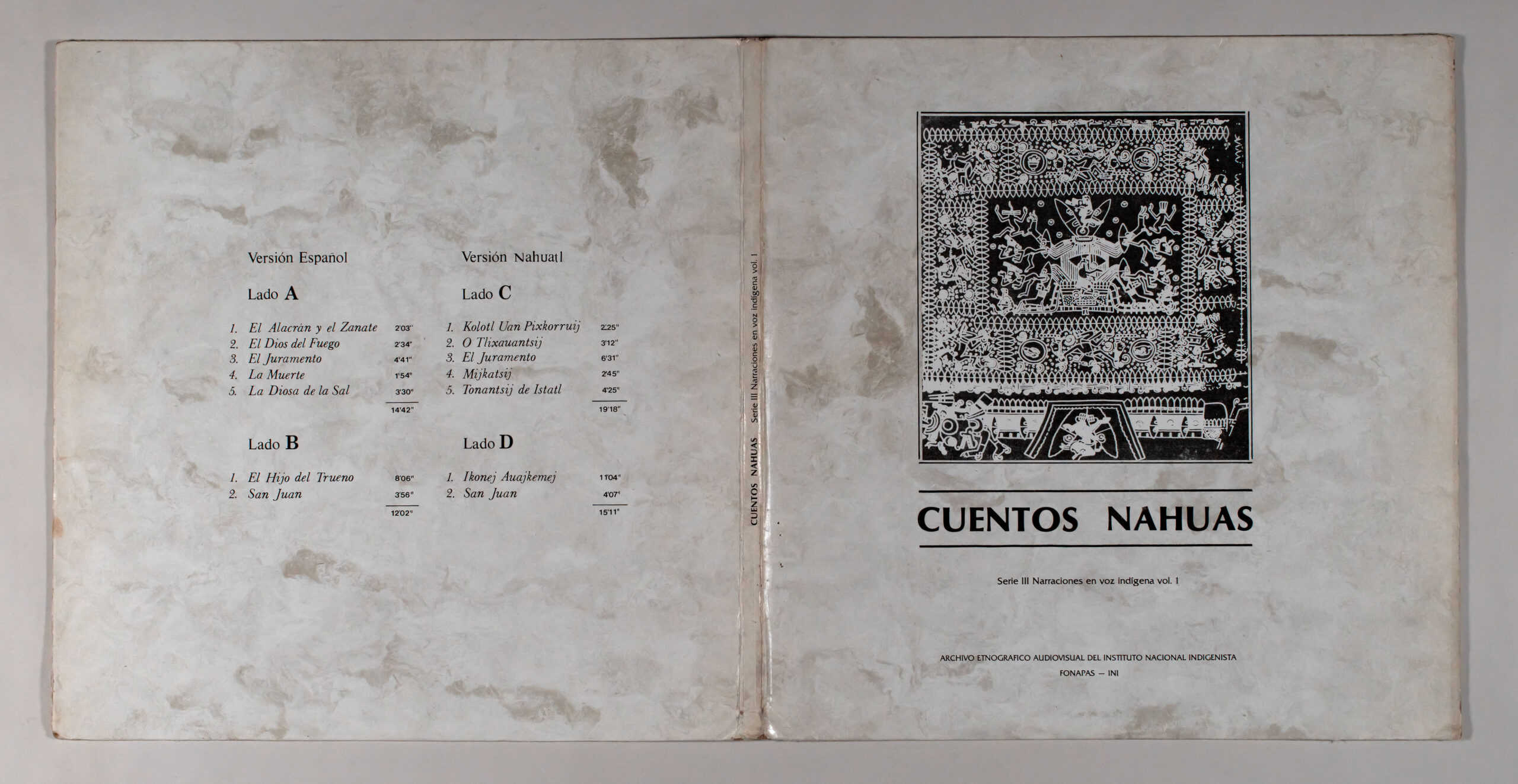

Label: FONAPAS-INI SERIES III, VOL. 1 |

Country: Mexico Genre: Folk World & Country |

Info:

NAHUA TALES

Series III Narrations in indigenous voice vol. 1

AUDIOVISUAL ETHNOGRAPHIC ARCHIVE OF THE NATIONAL INDIGENIST INSTITUTE

FONAPAS – INI

INTRODUCTION

The literary tradition teaches us that the story –without a doubt after the ritual and propitiatory poem– is one of the oldest forms of language products.

Probably to introduce role models, the guides of each community extracted explanations and usable consequences of natural phenomena and everyday experiences, and preserved them in the form of stories.

Nobody is unaware, but let us repeat it once more, that writing systems are relatively recent, compared to the extremely rich human experience that for the most part has been lost to us due to the lack of recording systems, or because man does not know how to decipher them when he discovers them. , already without the corresponding keys. In this regard, it is enough for us to recall the promises of Mayan writing.

Due to the foregoing, none of the contributions of oral transmission should be neglected, even if one is aware that a new way of penetrating into man’s past is not inaugurated, but that a process constantly enriched by the diligent collection of information continues. unbiased researchers, as every researcher should be, who disseminate their findings with the desire that new data appear to understand the past.

The stories gathered here have venerable precedents, from the traditions that Sahagún obtained from his Nahua informants, and the versions that Don Angel María Garibay and Doctor Miguel León Portilla have made in this century, to artistic recreations, even if they are from the Zapotec world. , by Oaxacan Andrés Henestrosa and Gabriel López Chiñas, if we limit ourselves only to the essential example.

Oral literature, the closer it is to the circumstances that originate it, does not attach importance to form. This is often naive, repetitive, even contradictory. The author, understood as a collective author, is not concerned about the use and even the abuse of copulative conjunctions and temporary adverbs to establish the sequences of the story. There are other things that matter: stimulating the imagination –no matter what level–, explaining the origin of a custom, the trait of an animal species, the usefulness of a vegetable, the moral quality of a human being.

It is almost useless to point out the inevitable contamination suffered by the ideas of the pre-Hispanic world. No one is surprised by the similarities, which are rather interpolations of Judeo-Christian religious thought, that we suddenly find between a myth from the Old World and another from the New.

It is evident that in the stories gathered here we cannot highlight the usual values that stem from the way of narrating (narrative rhythm, time management, lexical polyvalence, etc.), but rather the magical significance of the themes.

But, on the other hand, it would not be very sensible to demand that the men of one latitude think and feel diametrically opposed to those of another. There are many phenomena and experiences that are common: time –perhaps measured with the passing of the planets–, the spatial relationship, the life-death struggle, etc.

Magic numbers

For reasons that it would be long to point out now, all cultures grant magical value to certain numbers: three, seven, nine. In these stories, seven is the number loaded with powers: seven days of fasting, seven days after death one returns to life, etc. Why the seven? We do not believe that it is a choice of the pre-Hispanic world, since its week was organized in another way, but rather a transcript of the Semitic seven.

In order not to stay with the single statement, we could review the Nahua myths of creation, or those of the Popol-Vuh. We would verify, without a doubt, that symmetry is always important in the number of tests that a hero has to overcome, in the number of auxiliary animals, in the number of antagonists to defeat, etc. Generally, these cases are resolved with number four.

Kinship of myths

For mentalities loaded with magical elements, the manifestations of nature –animals or phenomena– do not have an independent origin from the divine will: the grackle squeals because it lessened the scorpion’s sting, the armadillo has seams because its gluttony made it burst, the turtle is squared in its shell by the antics of a child, etc.

In a comparative study – of which there are already many – surprising similarities are discovered between the myths of the Mesoamerican ethnic communities and those that occupied the territory of the United States of America.

The God of fire, a curious version of Xipe Totec, is subjected here to a domestic experience, with ill-treatment from his brothers-in-law, in which he is only recognized by his wife, and by the auxiliary animals that are never lacking in these stories of a special nature. wonderful.

The miracle, only one, occurs before the armadillo that eats an inexhaustible meat, as inexhaustible is the purifying nature of the fire, which destroys the scratches in the corn fields to give rise to the new birth.

With “El juramento” we can discover another interpretation of the eternal game of promises, fulfilled or not, with which human beings fight their ephemeral condition, and, furthermore, the hint of a heroic fight against the kingdom of death. The reader believes, for a moment, that he is facing a version of Orpheus, but the story takes a direction opposite to that of the Greek myth, although in both cases it is death that triumphs.

The hawk, as the totemic helper of the character in “El juramento”, does not fulfill his promise, since it only facilitates the arrival in the realm of death, but the recovery of the beloved does not occur. The story seems unfinished. The scarf is an interesting symbol that escapes those of us who lack specialized information.

Unusual feminine rebellion, in this world of indisputable subjugation, appears in “The Goddess of Salt”. In addition to having achieved a poetic account of insightful interpretation of the transforming task of nature, the relationships of the characters go beyond their function as mere symbols to assume that of living beings, capable of passions such as tenderness and resentment. At the same time that femininity is exalted, the vanity of the male is punished with the abandonment of the vexed wife.

“The son of thunder” juxtaposes various legends, including Mariana.

The miraculous fertilization, as miraculous as that of the earth, has multiple versions. In the Popol Vuh the maiden conceives because the skull of a hero who wishes to perpetuate himself spits it into her hand; Huitzilopochtli’s mother conceives him by her contact with a feather; The maiden in this story-The Son of Thunder-which is none other than Coatlicue reinterpreted, gives birth as a result of a cosmic pregnancy. Instead of envious brothers, the child will have an evil grandmother. In the successive destructions of the newborn we cannot avoid recognizing the solar evolutions. The turtle, carrier and protector of the child-sun, is none other than the earth.

The evil flies that sprout from the grandmother’s ashes deserve the reflections of a specialist in pre-Hispanic myths. For now, we are surprised by the coincidence between the box that the toad carries, and Pandora’s. But we know that the explanation of this case responds to other elements.

What we would like not to err in is the identification, once again, of the miraculously engendered child as the solar god, since the ascension to the heavens, with the lizard’s tongue to send rays, clarifies everything.

But his relationship with corn as a miraculous food capable of granting immortality assimilates the sun god with the god of this grass. There is a deep symbolism in this similarity, for what is corn if not transformed solar energy?

Finally, does the destruction of the grandmother represent the uprooting of a time of matriarchy?

The most recent contributions from literary research tell us, to the surprise of many, that man, throughout his poetic work, has handled a few basic themes, very few actually. What seemed like a very rich range of diverse subjects, with the deep examination has been reduced to essential questions: birth, old age, improvement or worsening of fortune, erotic fulfillment, etc.

What wonder, then, that these reported tales not invented by a peasant have a limited framework? However, as we will see, several attitudes and permanent concerns of the human being already appear.

There are two essential areas for man: livelihood and home. In the Nahuatl tales, preserved and recalled to the productive rhythm of the land, the milpa is the almost constant point of reference in which the latest achievements of the characters converge. The house, reduced only to preparing food and carrying out some cleaning tasks, remains in the background. Here human beings have no time except to make the land reproduce corn; and women, the man who will perpetuate the species. There is no time for entertainment, there is no room for metaphysical or eschatological inquiries.

Death is the other shore, that’s why it appears with them, the ones with the most surprising ending, they conclude in a different mask in these stories, that’s why two of a pile of bones.

The land of these men is fertile, hence they do not complain about it. However, happiness does not find the slightest welcome, it does not exist as an end or even foreseen. The collapse to which living beings are subjected is present in all angles of reality. He who loves doubts that he is reciprocated, and he kills love; the one who lives pleasantly because his food has flavor destroys his well-being with misunderstanding and violence; Parents who see the end of their long sterility lose their child because they could not channel it.

Let’s not confuse naivety with superficiality. What is thoughtfully elaborated is not always deep, nor what is spontaneous, incapable of penetration.

The stories still reflect a strong subjection of individual freedom to collective ends. The idea of the divine predominates in “The God of Fire”, in “The Goddess of Salt”, and, with different incarnations. in the “Son of Thunder”. In the absence of parents, who prevent the couple’s relationships, there are brothers-in-law and sisters-in-law as unmistakable villains.

If the man keeps the land in order so that sustenance is not lacking, the woman only reaches, as also happens in more sophisticated levels, the rank of slave who fulfills the tasks that cannot be postponed. Even after death she is stung by the obligations she failed to fulfill. That is why she returns to promote the well-being of her children.

Finally, we believe that it is still violent to submit oral narrative to the conventional form of the written language. It is well known that they are two different experiences. If here we have resorted to the presentation of texts, subject to the molds of the “literary” narrative, allow us the quotation marks, it is for reasons of clarity.

Just as the musicologist learns new transcription systems to record the different manifestations offered by his field, the oral literature researcher has to invent and apply forms of written language that do not betray the nature of the oral narrative.

Obviously, with these notes, and the sample of only seven Nahua tales, a hypothesis that involves all the tales of this tradition is not intended.

They are offered as a testimony that could help the specialist to obtain results, or approaches, of a more general nature.

The scorpion and the grackle

When the scorpion came into the world, it came with the intention of killing whoever it stung, but for this to be possible it had to fast for seven days. He was already on the sixth day of his abstinence, when flying flying he came to stand there on the ground a Grackle. The scorpion was lying next to a stone. Although afraid, the Grackle asked him:

–What are you doing little scorpion?

And the scorpion answered:

–Well, here I am fasting.

–And because? asked the Grackle.

–Ah!, because whoever I sting has to die. And for that I have to fast seven days. That is the mission that I fulfill. I no longer have a day left.

The Zanate said to him:

–Hmm…! I don’t think you’ll make it because you’re very small. Better what you should do is eat like me. If you could see how happy I am when I’m full! But the scorpion looked for reasons and defended itself.

Then the Grackle had an idea and said:

Let’s see, sting me better on one leg, let’s see if you really sting hard.

The scorpion, annoyed, stung his leg, but the Grackle told him:

–I did not feel anything. Better already eat, you are no longer suffering.

And the scorpion began to eat from his leg. It was just finishing, when the Grackle flew up to the branch of a tree, screaming loudly because the scorpion’s stings were tremendous.

It is since then that wherever the Zanate walks you can clearly hear how he screams. Strong was the real picket. But the Zanate saved the man of this world from being stung by a scorpion.

Nahuatl version

KOLOTL UAN PIXKORRUIJ

Kemaj kolotl ualki ipan ni tlaltipaktli, uala-

yaya kiualikayaya tlanauatili, para aki kitsa-

kanis mikiskia; pero para inoj … kipia para

moayunaroskia, mosauskia chikome tonatij

… ya youiyaya chijuasej tonatij … kemaj

patlantok ualki moseuiko iixtenoj se tetl,

kampa uetstoya nopa tototl, se pixkorruij;

ika maskej ika majmajtli kiijlijki tlenijki ki-

chiua nopanoj, kiijlia para ya moayurarojti-

kaj, mosajtikaj, –kiijli– ¡aaaj!, uan para

tlen –kiijli–, ¡jaaaj!, pos na aki nijtsakanis

–kiijli–, mikis… ¡aaaj!, axnijneltoka, –ki-

ijli–, tlauel tikuekuetsij para kan titetsakanis

mikis se tleueli, … kena –kiijli– san ya san

se tonatij nechpoloua, –kiijli– ¡axneli!

–kiijli– mejor ya xitlakua, –kiijli– para

tlen titlaijyuoijtikaj, –kiijli– si tijmachiliskia

na kemaj niixuitok… kontento nimomachilia,

mejor ya xitlakua, para tlen titlaijyouijtikaj,

–kiijli– uan ya modefenderoyaya nopa pil-

kolotsij, uankinoj pixkorruij kiijlijki,… –haber

xinechtsakani ipan noikxi, –kiijli– nijma-

chilis tlaj nelia tlauel chikauak titekua –kiij-

li– uankinoj kualanki nopa kolotl, kontsa-

kanik ipan iikxi nopa pixkorruy, –kiijli–

¡mmm!…ax tlen nijmachilik –kiijli– kampa

tinechtsakanik –kiijli–; mejor ya xitlakua

–kiijli– para tlen titlaijyouijtikaj –kiijli–

uankinoj nopa kolotsij ya pejki tlakua tlakua,

kemaj ya ixuitiyouiyaya uankinoj nopa pix-

korruy patlantejki moseuito ipan se kuauitl,

pejki tsajtsi tsajtsi chikauak… yeka namaj,

kemaj tsajtsi pixkorruij kuali tijkakij, para

kikokojki kampa kikuajki nopa kolotl; pero

tech salvarok tojuantij de ipan ni tlaltipaktli.

De timikiskiaj de piquete, yaya nopa kolotl.

The God of Fire

This was a man who just spent his time at home, sitting near the fire, and he didn’t even go out to work. But since his wife knew the powers she had, she never told him anything. When the time came to fell the forest, to burn and make cornfields, from early morning his brothers-in-law would go out to fell the forest. And almost to finish the slashing, they went to visit his brother-in-law and told him when he was going to start slashing, that time was passing and what would his sister eat if he didn’t work. And not content with this scolding, they still hit him with a rope. One day later, the lord of the fire told his wife to make him tortillas because she was going to go to her land to work.

When he arrived, the first thing he did was make a path around the cornfield, and around noon she set fire to it. From the great flames that went up to the sky, she was clouded by smoke. And everyone in town was scared.

When he returned home, he told his wife that the next day he was going to plant, and that as long as she put a liter of corn in it, and that he killed a chicken, it was fine.

The next day, when planting, the grackle, the parrot, the pich-pi, the peacock, the wild boar, the rabbit, the armadillo, the deer, the badger, the raccoon, and… other animals came to help him.

When the workers arrived, his wife had already set the table and they immediately sat down to eat. The food was excellent and plentiful to all except the armadillo. There was a piece of meat on each plate, and chilito and tortillas for everyone. But the armadillo began to make fun of the master of the house, and said that the piece he had received was too small for him, and that he was not going to fill it up with that. Then the Lord of the Fire told him to eat, and if he wanted more, to ask. And the armadillo began to eat and eat and the meat did not run out. And he ate and ate and the meat did not end, until he burst his belly. And then among the others they had to sew it on. And that’s why armadillos to date have wrinkles, like a rolling scar, on their belly.

Nahuatl version

GOD OF FIRE OR TLIXAUANTSIJ

Ni eliyaya se tetata tlen ax kinekiyaya tekitis,

mojmostlaj san itstoya ichaj, san tlitenoj lo-

kotstoya, ax pankisayaya para tekititi, asik

tiempo para kitlauisosej kuatitlaj gentes…

uan ya amo tekitiyaya, kualkaj kipeualtijkej

itexuaj tekitij tekitij, uan ya tlantiyouiasej

tekitij kipaxalotij inintex; uankinoj kiijliyaj

tlen horas kipeualtis tekitis uan tiempoj ya

panotikaj, kuali kiajuakej uan ax san inoj,

kuali kimakilijkej ika se lasoj.

Uankinoj kiijlijki isiuaj para tonilis makitlax-

kalchiueli, kej ya no yas kitlachiliti ikuatitlaj,

tonilik nelia yajki, kiyoualkotonato ikuatitlaj

kampa milchiuas, tlajkotona majkante kitli-

kuiltik temajmatij kej… kichijchijki se tlitl

kej kuaj nochi ¡puebloj nomajmatijkej!.

Kemaj mokuepato kiijlia isiuaj para tonilis

ya tookas, makinexketsa se litro sintli uan

teipaj makimikti se piyo ika inoj ya kuali.

Kintlanejki para tookanej… tsana, pixpix,

pavo real, kuapitsotl, kuatochij, ayitochej,

masatl, mapachej, tejón uan sekijnok.

De mokuepatoj tookatoj, aki isiuaj ya mochix-

toya ika mesa, ya tlateejtektoya tlakualistli,

motenkej, tlakuajkej kuali, pero ni ayitochij

ya kena kualanki pampa san se achitsij ina-

kayo kitlaluilijkej ipan platoj uan pilkentsij

chiltsij uan se ome tlaxkaltsitsij, ijkinoj pejki

kualani kiixkouik iteko; uan ya kiijlijki para

matlakua matlakua… uan tlaj ax kitlamia

kimakasej sekij; uankinoj ya pejki tlakua tla-

kua, tlakuajki tlauel, asta kej kuitlatsayanki,

uankinoj ¡compañeros kipaleuijkej para moij-

tiijtsonki sampa; uan yeka namaj kiualika

muestras nopa ayitochij de arrugas kuijkui-

lichtik iijti pampa ya inoj ax kitlepanitak

Tlixauantsij.

The oath

This was a young couple who loved each other. And although the love between the two was reciprocal, the husband wanted to test if his wife’s feeling towards him was true. One day he told his wife:

–I love you so much! I love you more than myself. I love you more than all the gold in the world. And I want to swear to you that if you die I will have to die too.

And his wife replied:

–I believe you, because I love you the same way too. And your sincere words make me very happy. I can’t live without you either.

And so they established an oath forever.

Then one day her husband went out to work in the bush, where she was with her laborers, delimbing trees, the largest trees. The young man climbed onto one of these and tied himself up so as not to fall to work. And since he had already reached an agreement with his workers, he yelled at them from above:

–Now they go to my house together and tell my wife that I fell from a tree and killed myself, to get everything ready in the house for when you take me.

The pawns did so. They all came with sad faces to give the bad news to her wife, who burst into tears. They immediately withdrew to go and bring the false deceased. Remembering her oath, without further thought, the woman looked for a rope and hung herself.

When the peons returned carrying her husband, they found the corpse of her wife hanging from a beam, with her tongue sticking out.

The man regretted his attitude a thousand times, but he had no choice but to bury his wife.

The husband, who was an orphan and had no one else in the world, every time he went to the milpa he lost interest in working. He just kept thinking about his wife, and he would start crying at the foot of a tree. And one of those days when he went to the cornfield to work and couldn’t, and he sat down to cry at the foot of the tree, a hawk flew up and stopped and asked him why he was crying. The man looked up, saw the hawk standing on a branch and replied that he suffered great sadness for the loss of his wife. And he told her what happened. And so, for several days, the hawk accompanied the man who mourned his misfortune. One of those days the hawk told him not to cry so much anymore, that if he loved his wife so much, that if he really couldn’t forget her and wanted to see her again, that he could help him and that he could find her in… a certain place .

Then he gave her a red handkerchief and told her that she had to fast for seven days, and that if she ate in those seven days, she would stay there forever, where she was.

–Go away! –She told him. With this scarf you will start your way. First you will find small crosses, but when you find a big one there is your wife. When you arrive, give him the handkerchief. She already knows what she means.

The man did what the hawk told him, and when he saw a large cross, he did indeed find his wife there, and he handed her the handkerchief. Right away he told her that he loved her very much and that he missed her and that’s why he had come to see her. But now they could go back and live together.

The woman was cooking, very busy, and she replied that she didn’t even know him, that she lived very happily with her husband. That’s when the lady’s new husband arrived and asked her who that man was. And she replied that he was her uncle. “Ah! said the husband, then give him something to eat because he must be tired and hungry.”

After eating, the new husband, who was a muleteer, went out again to harvest. And he returned at night, with his beasts loaded with corn.

The muleteer and his wife went to sleep in a room and they gave him another room. When the muleteer had fallen asleep, the first husband looked for a rope and went over to where she was sleeping and began to tie her up to take her away. But when he wanted to carry her, a bunch of bones fell to the ground.

Then the man saw that he was alone with death in the cemetery.

Nahuatl version

OATH

Ni eliyaya se telpokatl uan se ichpokatl, mo-

namiktijtoyaj, itstoyaj ya sansejko, tlauel

moileuiyayaj, tlauel moamatiyayaj, pero tla-

katl ax eltoya conforme para kiijliya ya isiuaj

tlauel kiileuia, uan se tonatij kiijli tlaj neli

tlauel kineki; –kiijli–, para kena, “tlauel ni-

mitsneki,” – “pues na nojki igualmente, nij-

neki nimitsijlis para tlaj tlauel tinechneki…

si tlaj ta timikis, na no nimikis” –kiijli–

“pampa tlauel nimitsileuia; jaaaj! -pos na

nojki” –kiijli– “nojki, ¡cuando niitstos sin

ta!” –kiijli– uankinoj mojuraruilijkej para

nochi tiempo monekisej.

Se tonatij kistejki tekitito nopa tlakatl, ika

¡peones, kuatitlaj… ya inijuantij ya motla

altoyaj de acuerdo, uankinoj ya tlejkok ipan

se kuauitl, kuajkapaj para kimaximati, moil-

pik ika se lasoj, para ax uetsis kemaj temos,

uankinoj desde uejkapaj kintsajtsilik ¡peones,

para mayakaj ichaj kiijlitij isiuaj para ya

mokuatepexouik uan momiktik, –nelia–;

nopa ¡peones yajkej nochi tristes asitoj, pam-

pa kiuikaj mala noticia, kemaj kiijlijkej isiuaj

tsajtsitejki choka… uankinoj kiijlamijki nopa

Juramento tien moitokej, nopa peones nimaj

mokuapkej para kikuitij nopa difunto, uan

nikanij, isiuaj ya kiteemok se lasoj uan mo-

kuauiyonik, momiktik; kemaj nopa peones

mokuapatoj ika nopa difunto kiitako nopa

tlakatl, para neli isiuaj momiktijtok; kuaui-

yontok ipan se viga, asta nenepilkistok, motsi-

majmatik uan moarrepentirok mil veces pero

ax kipixki mas remedio ke san kittokas, de

uankinoj mokuesok; youiyaya tekiti imilaj,

ayok ueliyaya tekiti, pampa san ya inoj ki-

seemejtok, uan peua mochokiliya, ijkinoj pa-

nok miak tonatij, itsintlaj se kuauitl moseui-

yaya choka kemaj youiyaya tekiti, panok se

ome tonatij, uan ijkinoj kipasarouiyaya, ayok

tekitiyaya, pampa nopa telpokatl eliyaya ik-

notsij, ax akij kipiyaya… uan se tonatij teki-

tito imilaj… ax tekitik… moseuito itsintlaj

nopa kuauitl ika ipan moseuiya, kemaj pa-

tlantok ualki se kuajtli moseuiko itsontlaj;

uankinoj kiijliya, (nopa kuajtli),-“para tlen

tichoka”, kiijli, uankinoj ya nopa ajkoitak

kitlachilik nopa lokotsijtok se kuajtli, “jaaaj!”

–kiijli– “na nipjpia se ueyi kuesoli” –kiijli–

“pampa nijpolojki nosiuaj”-kiijli- “mijki

ya” –kiijli– “¡mmm!” nochi kitlapouiltik

tlen ipantitoya. Bueno… panok miak tonatij…

uan nopa kuajtli kiitak para tlauel mokuesoua,

se tonatij kiijlijki, para maayok mokueso, …

si tlaj nelnelia tlauel kineki kiitas isiuaj, tlaue!

kiijlamiki, kej ya kipaleuis; uankinoj kikixtik

se payoj chichiltik kimakak uan kiijlijki– “ya

inij, ya inij ika tias” -kiijli- “xijkonana

moojui” –kiijli– “pero amo titlakuas chi-

kome tonatij” –kiijli– “porque si tlaj titla-

kuas, uankinoj ax timokuepati kampa tiasiti”,

kejnopa kichijki nelia… kikonanki iojui nopa

tlakatl, uan kiijlijki… “timelajtias miak krus-

tsitsij” –kiijli– “kampa tikasiti se ueyi krus,

nopanoj itstok mosinaj” –kiijli– neliya …

asito kampa nopa eltok se ueyi krus, nopanoj

itstok isinaj, lo kej primero kichijki kimakak

nopa payoj chichiltik uan kiileuito nimaj sam-

pa, pampa kiitato tlauel yejyektsij; –kiijli–

“jaaaj!” –kiijli– “pero na ayok nimitsijla-

miki, na niitstok contento, nikanij” –kiijli–

“na ax nimitsixmati” -kiijli- “pero na

nijneki nimitsuikas”-kiijli- uankinoj asiko

iueuej se arriero tekiti kisakatikaj sintli… asiko

kitlajtlanilij ajkia nopa tlakatl, “jaaaj!”

–kiijli– “ne notlayi” –kiijli– “aaaj!”

xijtlamaka” –kiijli– “ualaj siyajtok uan

mayantok” –kiijli–; tlakuajki uan nopa

arriero sampa yajki para imilaj sinkuito, ya

ualato ya asta tlayoua, uankinoj tlajuajkej

uan ya kochitoj, uan nopa ten achtoui iuenej

kimakakej se kuartojtsij sejkanok, uan ya

nopa arriero nimaj kochki; uan nopar tlakatl

ax kochki, kiteemok se lasoj uan yolik

moechkauijtiyajki kampa uetstokej inijuan-

tij, uan nopanoj kiilpito nopa isinaj: pero ya

kemaj… para kitlalanas kikechpanos, uanki-

noj tepejki nochi nopa iomiyo, uankinoj mo-

makak kuentaj para itstoya uan mijkatsij

kampa santo.

Death

There is a belief that in the past one did not die forever, but came back to life after seven days. This was precisely what happened to a man whose wife died young and she left her little children helpless.

When that man went to work in his milpa, the deceased would come back to life, and would show up at his house and sweep and wash and bathe and comb the children and make tortillas, and, finally, leave everything in order. before noon when her husband returned to eat. And she would leave then, recommending to the children that they not tell anyone that she was the one who did the housework, much less her father.

The man did not stop being surprised by what was happening in his house, since he himself had buried his wife and there was no one to do the chores.

One day he asked his children, and they told him that his mother came in the morning.

So the husband was vigilant the next day, and he surprised her wife making her food, and he saw her very beautiful. When she noticed her, he told her not to get close to her and not to touch him, because if she did, he would never see her again.

But the man replied that he saw her very beautiful and that he wanted to hold her in her arms. And without thinking about it anymore, the man went to embrace her, but as soon as he had touched her, her bones scattered on the ground, and he had to bury them again. And the lady never came back.

Nahuatl version

DEATH OR MIJKATSIJ

Achtoui moneltokayaya kej tojuantij ax ti-

mikiyayaj tlen nelnelia, sino kej de ya timik-

tokej timokuapayayaj ipan chikome tonatij;

uan de inoj se tlakatl mijki iichpokaj siuatl;

akej nopa isiuaj eltoya… uan kinkajtejki iko-

neuaj kuekuetsitsij, uan kemaj nopa tlakatl

youiyaya tekiti imilaj uankinoj isiuaj mokua-

payaya… ika kualkaj tlachpanayaya, kinal-

tiyaya ikoneuaj, kintsikauasuiyaya… uan tei-

paj tlaxkalchiuayaya uan kintlamakateuayaya;

kemaj asiyaya iueuej ya onkaj tlaxkali uan

kali tlasenkauali… pero teipaj kikuesok, uan-

kinoj kintlajtlanilik ikoneuaj, ajkia kejnopa

ualaj kichiua tekitl ipan nopa kali, uan isinaj

ya ya miktok, uan ya kitoktok, uankinoj kiijlij-

kej para ualaj ininana, ipan se kualkaj ya

ualaj kichiua nopa tekitl, uankinoj tonilik

kipijpixki, tlejkok ipan se tlapaj… kemaj kiits-

tejki nopa ualaj isiuaj, kalakiko kalijtik, pejki

kichiua tekitl, tlaxkaloyaya, uankinoj temok;

kinojnotski, –kiijli– “jaaaj!… ya tiualki”

–kiijli–, “pero namaj ayok tias”–kiijli–

–kiijli– “porque uankinoj kena nimikis”

–kiijli– “pero na nijneki, ximokaua” –kiij-

li– “porque ya tlauel nimitsileuiya, uan tlauel

nimitsijlamiki”, uan sin pensarlo más nejnen-

tikiski kinajnauato, pero kemaj kinajnauato

nepa tepeuito iomiyo, uankinoj kena ax kipi-

xki mas remedio kej kitookato, pero de uan-

kinoj ayok kemaj mokuapki mas isiuaj.

The goddess of salt

In very ancient times, man ate his food, either cooked or raw, but without salt. In those days there was a man who worked his cornfield every day. And he was the only one who had the happiness of eating cooked and salted. Only he was lucky to eat the flavored food, but he didn’t know that his wife took the salt out of his own body.

One day his wife invited the sisters-in-law to eat mole, and since the food seemed very tasty, they asked her how she did to make the food flavorful. She refused to tell them the truth, but the sisters-in-law insisted on the matter so much that she finally told them that when she bathed, she rubbed the droplets of water that remained on her body, with her hand downwards, and cut them off with a fret, while fall into which they became lumps of salt. And that with that she made the food.

The salt lady had told them the truth, but she also asked them to keep the secret, because if her husband found out she was going to hit him.

Then the sisters-in-law ran to tell her brother, but he did not believe them. So they returned to the lady and asked her to give them some lumps of salt so that they too could make the food flavorful, but it was just a lie. They took the lumps of salt to her husband, who was thus convinced.

One day, then, he set out to watch her wife when she went to bathe, and verified that what her sisters had told him was indeed true.

When her wife finished bathing, she carved her body with her hands, caught the drops of water with a plate and filled it with pure salt.

The man walked away from her from the place and went to wait for her at her house. There he scolded her and scolded her and then he brutally quartered her, while he told her how could he feed her dirt from her body, how could her woman be so filthy.

She began to cry and cry and cry until the man took pity on her and began to comfort her. But everything he did was in vain, because she kept crying and crying.

Then her brothers-in-law came and also begged her to shut up about her, but they couldn’t comfort her either.

Then the salt lady said to her husband:

–I fed you everything well prepared and with flavor, they ate to your liking, and no one ate like you. but since you’ve hit me, since you’ve brutally quartered me, and since I don’t want you to do the same to me again, I’m going to leave forever, I only ask you to bring me my punt.

The sky had clouded over from the moment she started crying. And immediately it began to thunder and lightning and suddenly there came a tremendous downpour and the streams and rivers swelled. And then she took her punt from her husband’s hands, climbed on it and went into the water, and her husband and her sisters-in-law begged her to come back. But her pleas were useless, because she got into the water and went into the sea forever.

For this reason, when one cries, the tears taste of salt, and the sea is also salty like tears, because the goddess of salt is there.

Nahuatl version

GODDESS OF SALT OR TONANTSIJ DE ISTATL

Achtoui tlakamej yanejya tlakuayayaj iksitok

o xoxouik, pero amo tlakuayayaj poyek, pero

se tlakatl kena tlakuayaya poyek, tekitiyaya

imilaj, ualayaya tlakua tlajkotona, siempre

poyek; pero ax kimatiyaya para isiuaj kikix-

tiyaya nopa istatl ipan mismo itlakayo… uan

se tonatij nopa isiuaj kininvitakok iuesuaj se

tlakuali, uankinoj kiijlijkej inijuantij, para

kenijkatsaj kichiua nopa tlakuali tlauel ajuiak,

ya ax kinekiyaya kinijlis, pero tanto tlaue!

kinrogaruilijki, kinijlijki, para ya kemaj yout

omaltiya, nopa apojpoloktli tlen mokaua ipan

itlakayo ya inoj kiuajuatania ika imak uan

kitsakuilia ipan se plato, uetstinemi ya eli

istatt; “¡eeej!” uankinoj, kiijlijki iniknij, para

isiuaj kitlamaka poyek, pero de ipan mismo

itlakayo kikixtia nopa istatl; uan ax kineltokak

ya, sampa yajkej kiitatoj para makinregalaro

se pilkentsij, para no motlakualchiuisej po-

yek, inijuantij no;… uankinoj kinmakak, pero

kinijlijki, para ax akaj makiijlikaj, porque si

tlaj kimatis iueuej kimakilis kuajkualtsij.

Pero nopa istatl ax akaj kitekiuijki san kikaj-

kayajkej, sino kej kiuikilijkej iniknij uan uan-

kinoj kena kineltokak, tlen kiijlijkej iueltiuaj;

uan asik se tonatij kipijpiyato kampa maltia

uan nelnelia kiitak tlen kiijlia iniueltej, kiitak

para kemaj tlami maltia nopa apojpoloktli

mouajuatania uan kitskuilia ika se plato,

temi de puro istatl; uankinoj ya mojkuenik de

nopanoj. Kichiato kalijtik, asitinemi pejki

kiajua kiajua, uan asta kemaj kiijlik uan ya

pejki choka mejor, mokuesok para tlen kej-

nopa kichiua, uankinoj kiijlijki –”na nimits-

tlamakayaya ajuiak”, kiijlia– “nochi tiempo

san ta titlakuajki poyek”, –kiijli– “ax akaj

tlakua mas seyok komo ta, ajuiak”; –kiijli–

“pero namaj tinechmakilik kuajkualtsij”,

–kiijli– “tlauel tinechkokojtok”, –kiijli–

“uan komo ax nijneki sampa kej inoj xinech-

chiua, mejor nias de nikanij” –kiijli–; uan

pejki choka, –uan ya kiijli– “para maax

choka, mejor ya, mamoseselti” –kiijli–…

asikoj iuesuaj, nokikonsolaroyayaj, pero

cuando, ya kiseguiroyaya choka, uankinoj

kiijlijki iueuej, para makikuiliti ibatea; uan

komo pejki choka, tlamixtenki eluikak uan

pejki tlatomoni, pejki tlauitekij. Nopa iueuej

ax kipixki mas remedio kej kikuilito ibatea

uan nopanoj kalajki. Kiyakatsakuiliyayaj iue-

suaj, pero ax uelkej; iueuej tlauel lo mismo

kichiuayaya, uan ax kanaj; kiski, yajki kala-

kitoj ipan atl uan de nopanoj yajki asta ipan

mar. Yeka namaj tojuantij kemaj tiixchojcho-

kaj, poyek toixtenayo; uan mar nojkia poyek,

pampa nopanoj asito Tonantsij de Istatl.

The son of thunder

This was a very angry old woman who treated you beaten for anything at all. And this old woman had a very pretty daughter who was lucky enough to live martyred by her mother. The woman never let her daughter out or talk to anyone. And she watched her and scolded her.

When she went to wash at the creek, she would leave her locked in a large drawer, where she would fit very well. And since the stream was close to her, the woman heard her daughter laughing, and she would come back and open the box and ask her who was she laughing with, and her daughter would say no one. And so time passed and then the woman came to realize that her daughter was pregnant.

The woman threw rays of courage, but she could do nothing anymore. Some time later the son of that young woman was born.

Seeing her grandson, the first thing the grandmother thought of was killing him and eating him without the girl noticing. A few days later, the woman sent her daughter to wash in the stream, and told her to leave the child sleeping in her cradle. The witch grandmother killed him and made him into a mole.

Back from washing, at noon, the boy’s mother was already hungry. Then her mother, who was waiting for her with… rich mole! She told him:

-Sit down! He’s already eating, the child is still sleeping.

The mother sat down to eat, but as she put the morsel into her mouth, her meat spoke to her, telling her not to eat it, that it was her own child, and that if she ate it again she was really going to die.

The mother got up and went to her crib, and there she only found a table well covered with diapers and blankets that the grandmother had prepared so that she would not notice right away.

The mother became very sad and asked the grandmother why she had killed the child, and she told her that because she did not love him, because she did not have a father.

Then, since no one ate the food anymore, the mother picked it up and went to bury it in the patio.

Six days later, a corn plant was born. The grandmother, seeing her, got angry and ordered the rabbit to cut her up and eat her.

A few days later, the grandmother went out to see if the corn plant was still in the patio. There was a well-arrived ear of corn, and at the bottom, the dead rabbit.

The grandmother with one pull ripped the cob and shelled it. She then put the grain to boil, but the pot broke in two.

She then took the nixtamal to grind it to the metate, but the metate and the hand of the metate broke in half. And then she, very angry, took the nixtamal and threw it into the river for the fish to eat. But the nixtamal was the child again, and the fish only ate his meat, and the bones, on the river bank, began to cry.

The Virgin Mary, up in heaven, heard a child crying at the water’s edge. She went down to see and saw that he was a child, whose body the fish had eaten, and she called to them and told them to return the meat they had eaten.

And the fish obeyed him and the boy returned to his usual condition, as if nothing had happened to him.

The Virgin commissioned the turtle to take care of him and the turtle did so. She always carried the child on her back, and since he was very naughty, she scratched his shell. And that’s why turtles have so many stripes on their backs.

So the days passed and the boy grew up. And one day he wanted to visit her mother, and he asked the turtle, whom she called aunt, for permission, and she granted it. And she went to see her mother, whom she found sitting, very sad, sewing clothes at the door of her house.

The boy climbed a tree next to the house, and from there he began to throw leaves at his mother, and the leaves were going to fall on his seam. The mother looked up and saw her son. The boy told her not to make noise because her grandmother was going to listen to them. The mother told him that the grandmother was in the yard and afterwards they talked about everything that had happened. Then the boy said:

–I’m going to see my grandmother.

His mother replied:

–Better not go because she can kill you!

The boy reassured her by telling her not to worry about her, that she would see that she could do nothing to him. And he went to see his grandmother.

The grandmother had removed her scalp and was expelling it to remove the lice. The boy collected some dirt, climbed up on the loft and from there he threw the dirt on her head without her noticing it. When the grandmother wanted to put her scalp back on, there was no way she would hit her head again, and she burst into tears.

Then her grandson appeared and said:

–Don’t cry anymore, Grandma. I am going to help you. I’ll take the dust off your head.

And immediately it transformed into a mosquito and flying and flying in less than a minute it had already removed all the dust. And the grandmother was able to reattach the scalp to her head.

Then they stood face to face and the boy, very determined, told his grandmother:

–Even though I am a child and you are a lady, what do you think, grandmother, if we see who can do more?

And since his grandmother agreed, the boy said:

–I am going to spread a cup of sesame seeds on the ground, and when I return you will have collected all of it, without dirt and nothing.

When he returned he found that her grandmother had collected only a little, and even that, with dirt, and he made fun of her and said:

–Not like that, Grandma. You dumped a lot of trash.

Then the grandmother said:

–Okay, but now it’s my turn. I’m going to water a liter of joy, and then I’m going to bathe. By the time she comes back you’ll have it all together.

The boy called the birds to help him, and in a minute they had already collected all the joy.

When the grandmother returned, the boy told her:

–Now let’s see who wins. The two of us will bring water from the river in a net, and you will go first.

Grandma went and came back, but she brought the net empty, and she was all wet. And the boy made fun of her again, and went to the river and returned with the water inside the net.

Seeing him, the grandmother exploded with anger, because in everything, her grandson was winning, and she said:

–Now I’m going to burn you!

And she put wood in the oven, and when it was burning he put the child in. But, before entering the oven, the boy had already turned into a mosquito and flew away. The grandmother added more firewood, and when she heard that she thundered, she thought that the days of her grandson ended there.

The next day she got up early and took a tray and a knife, and she was about to uncover the oven when her grandson spoke to her behind saying:

–You were thinking of eating me dead and cooked, weren’t you? But here I am, and now it’s my turn.

And the boy put more firewood in the oven and when it was hot he threw it into it. Then he took out the ashes and told the toad to throw them into the water, warning him not to open the box in which he was carrying them.

But since the toad heard a noise inside the box, he uncovered it. And then all kinds of poisonous flies came out and began to bite him. Quickly, the toad closed the box and threw it into the sea.

The toad arrived all stinky from fly bites to tell the boy what had happened.

The next day the boy sharpened his knife and set out on the road to the sea, where he met a huge lizard that wanted to devour him. Then the boy said:

–If you want to eat me you need to open the trunk more.

The lizard opened its trunk further and in that the boy cut its tongue with his knife, and the lizard was mortally wounded and its tongue was left flashing. Then the boy said:

–This will serve to drop lightning.

And he took her up to heaven.

Nahuatl version

SON OF THUNDER OR KONEJ AUAJKEMEJ.

Ni eliaya se tesisi, tlauel mosisiniyaya kej

por se tleueli nochi tlanauatiyaya mosisinij-

tok; uan kipiyaya se iichpokaj tlauel yejyek-

tsij uan ax kemaj kikauiliaya maajkia kika-

maui, nochi tiempo kiajuayaya uan tlauel

kimokuitlauiyaya; kemaj youiyaya tlachikue-

niti atlajko kikaltsakteuayaya ipan se ueyi

kajo kampa ikatiyaya kuajkualtsij; pero ke-

maj… ya kikajki tlachikuenijtikaj, kikajki

iichpokaj uan ajkia inoj uan uetska; uala

kitlachilia ya ax akaj itstok tlaijtik, kikajla-

poko –kiijlia– “ajkia uan tiuetskayaya”

–kiijlia– “ax akaj na niitstok noseltsitsij

jaaaj!” panok tiempoj kemaj kiitsteejki iichpo-

kaj ya ya tlanemiltia, kualanki tlauel para

kej inoj eltok, pero tlen ijki kichiuas; ax uaj-

kajki kipixki se okichpiltsij; kualanki pero ya

kipensorok komo kiera para kimiktis uan

kikuas. Uan se ueltaj kititlanki jichpokaj

para mayoui tlachikueniti, ya yajki, kiijlijki

makikajteua ikonej ya kimokuitlauis, ya yaj-

ki tlachikuenito; kemaj ya mokuapato tlaj-

kotona, ualajki ika… ya mayantok, kiijlia

tlaj ya tlakuas, kiijlia inana para maya moseui

matlakua, kej okichpiltsij kochtok, ijkinoj

kena moseuijki para tlakuas, pero antes de

kikuas nopa tlakuali, uankinoj tlatojki ikonej,

para maax kikua, porque tlaj kikuas uankinoj

kena mikis; moketstikiski inana nopa okich-

piltsij kitlachilito touajtli… tlen ijki touajtli,

san se pedazo kuauitl eltok kuali piktok ika

pestetl uan ika pilisali, tsajtsitejki uan kire-

clamarouilito inana para tlen para tlen kimik-

tik para tlen ijkinoj kichijki uan iixuij, uan

kiijlia ya para ax kineki kiitas pampa ax

kipia itata, uankinoj… komo ax akaj kikuaj-

ki nopa tlakuali, inana nopa okichpiltsij kiui-

tejki kitookato ipan kaltenoj, ipan patioj;

ipan chikuasej tonatij ixuak se tsontli toktli,

¡aaaj!… nopa tesisi kualanki para para kiita-

to eltok nopa toktli, kimuuatik kuatochij para

makitsonteki uan makikua, panok se ome

tonatij, sampa kitlachilito nopa toktli ya…

ya eltok se ueyi sinmolotl san kontilanki,

kixipejki uan kioxki uan tlanki kinexketski,

pero nopa nexkomitl kuitlatsiyanki, nepa te-

peuito nextamali; ijkinoj kualanki kinejki ki-

tisis, postejki metlapili uan metlatl tlatlapa-

kak; uan komo ax uelki kitisi, uankinoj kikui-

tejki nopa nextamali kikauato ipan se ueyi

atlajtli, para makikuakaj michimej, pero no-

panoj sampa mokuapki okichpiltsij, nopa…

nopa nextamali, pero komo kuekuetsij eliaya

ya kikuajkej michimej uankinoj mokaajki san

iomiyo, uankinoj nopa inmiyotsitsij pejkej

chokaj, uankinoj Tonantsij desde eluikak ki-

kajki para tsajtsitikaj se okichpiltsij; temok

kitlachiliko, ya kiitako para nopa okichpiltsij

san iomiyo tentok, uankinoj kinnauatik nopa

michimej para makikuapakaj tlen kikuajtokej,

nimajantsij kichijkej lo ke tlen kinauatijki,

uan al momento okichpiltsij sampa elki de

nuevo, uankinoj Tonantsij kinauatik tortuga

para makimokuitlaui, mano… kiiskalti ya,

uankinoj nelia ya nochi tiempo kimaamajtine-

miyaya, pero komo ni ya pilokichpiltsij tra-

vieso, kipanuauatstinemiyaya, uan yeka namaj

nopa tortuga tlauel panuauasatik; ya kichi-

uelik. Panok tonatij kiijlia nopa tortuga (o

iaui) –kiijlia ya–, para ya kitlachiliti inana,

tlen ijki kichiua; ya kimakak permiso, uanki-

noj yajki nopa okichpiltsij kitlachilito inana,

kitlachilito ya tlajtsontikaj puertajtenoj, uan-

kinoj ualtlejkoto ipan

kuauitl uan de

noj kuaixko pejki kitepeuilia tlasoli; uan ya

ajkoitak inana, nimaj, kiitak para ikonej;

uan kiijlik para maax kichiua ruido, porque

kikakis isisi ne kaltenoj itstok, kiijlia kiijlia

para maax kipia cuidado “komo kiera na

nias nikitati” –kiijlia– uan nopanoj tlauel

kuali motlapouilijkej de lo ke tlen kinpasaroj-

tok, buenoj… –kiijlia– “namaj nijtlachiliti

nosisi” –kiijliaya kiitato mokixtilijtok ikua-

kuetlaxo, moyejyektiltikaj, pampa kinpiyaya

atimimej; uankinoj ya tlejkok tlapaj, ika se

kentsij tlalkuanextli nopanoj kikuapopote-

chuelik; uan kemaj nopa tesisi kinekiyaya

mokuatlaluelis ikuakuetlaxo, ayok ikan uelki;

uan ijkinoj kiijli ya para para, ijkinoj ya

kipaleuis; mokuapki sayoltsij, pejki no patla-

ni ikuayayaualkaj, kitlamokuilik nopa tial-

kuanextli; uan uankinoj ya mokuatialuelik

ikuakuetlaxo, teipaj mokaajkej mosentlachil-

tokej, uankinoj kiijli nopa okichpiltsij, “na-

maj kena” kiijlia, “sisi matimotlanikaj”

–kiijlia– uan komo ya kualantok, kiijlijki

para kena, “bueno”… –kiijlia– “pos namaj

na nimitstepeuilteuas se litro ajolij uan na

nias nopeka ninejnemiti uan kemaj niasiki ta

ya tipejpentos, pero amo ika tlasoli” –kij-

lia– ya onyajki nopeka nejnemito, ualato ax

tlen, kentsij kipejpentok, kipejpenki kentsij,

pero ika tlasoli, ika nochi tlali; ualato –kiij-

lia– “¡mmm!” tlaj ax tlen, ax tlen tipejpenki”

–kiijlia– “uan tipejpenki asta ika tlali”

–kiijlia– “bueno…” –kiijlia–, “pero na-

maj na nias” kiijlia isisi, nankinoj kitepeuil-

tejki se tasa uajtli “uan na nionmaltiti” kiijlia,

“uan kemaj niualati ya titlantos tipeipentos”

–kiijlia– yajki uan san ne ompoliuito ya

kinojnotski tototsitsij, ipan se ratito kitla-

mipejpenkej nopa uajtli, kemaj ualato nelia

kualaniyaya isisi, “bueno…” kiilia, “pero

amo xikualani sisi”, kiijlia, “porque namantsij

timotlanisej sampa”, kiijlia, “namaj tiomej

tijkuitij att ipan ni ayat!”, kiijlia, “pero namaj

achtoui tias ta”, kiijlia, “tijualiks atl ipan

nopa ayatl”, kiijlia, yajki nelia, se ratoj nopa

tlantok xoloni uan ax tlen kiualika ipan nopa

ayatl, “namaj na nias”, kiijlia, nelia, san

kontilanato nopa atl, nopa kiualika, “juuum!”

pero nelia kualaniyaya isisi para ya kena

kitlantikaj, uankinoj kiijtojki isisi “para na-

maj na nimitstlatis” kiijlia, kitemilik kuauitl

nopa hornoj uan kitlikuiltik, kemaj xauantoya

uankinoj kiitskik nopa iixuij uan kimajkajki,

pero antes de kalakiti ipan tlitl uankinoj ya

mokuapki sayoli, yon ax momakak kuentaj

kej kistejki yajki, tonilik nopa tesisi kualkaj

mejki ika ilavandeja uan ika se kochiyo; para

kikixtis iixuij uan kikuas, pero kikaktejki ya

kikamauia ika ikaj, kiijlia, “tijnekiyaya ti-

nechkuas niiksitok ax ke”, kiijlia, “pero na

nikaj nitstok”, kiijlia, “pero namaj na nimits-

majkauas nopanoj”, kiijlia, uankinoj no ki-

tlikuiltik nopa hornoj, uan se momento san

kuali tlikauantok ya uankonj ya kena kimaj-

kajki uan kena kimiktik, tonilik kikixtik ikua-

nexo uan kititlanik sapoj makimajkauati ipan

mar, pero kiijlijki maamo kitlapo nopa kaji-

taj kampa youi, maax kichiueli kuentaj; pero

komo ni sapoj kikajki para youi ruidos iijtik

nopa tlen kiuika, kitentlapok; kitentlapojti-

nemi, kiskej miak sayolime uan kitlamokuaj-

kej; kemaj mokuapato kitlapouilik okichpiltsij

lo ke tlen ipantik, uankinoj kualkantsij ipan

inoj tonatij motlatentilik no, uan yajki kitla-

chilito kampa kiijlijki sapoj, kampa kikauato

nopa kuanextli, ya nopanoj kiitato se lagartoj

uetstok ueyi; kemaj asito, kiten… mokamatla-

pok para kinekiyaya kikuas, uankinoj kiijlia,

“tlaj tijneki tinechkuas”, kiijlia, “xijtlapo

mokamak mas”, kiijlia, “uan nelia kitlapok

ikamak, uan ya san kontekilik inenepil, nepa

uetsito, pejki pepetlaka, uan nopa lagarto

yajki para ipan atl, ya casi miktiyaj; uan

inenepil komo pepetlakayaya, uankinoj kiij-

tojki ya nopa okichpiltsij, para inoj serviros

para kimajkauas rayos, uan kitlejkoltik para

eluikak, para Auajkemej.

Saint John

Once upon a time there was a family made up of a man and a lady who had no children. The gentleman was a very hard worker. And in the month of June he planted pumpkins. When they were given, he thought, he was going to eat them tender or solid. But the bush spread and spread, and spread, and gave nothing, until he finally gave a gourd. Since she was the only one, he took great care of her, and he didn’t want to cut her tender. He wanted me to rock well. because it was a big pumpkin, a little long.

Time passed. And one morning, when the man arrived at his cornfield, he found the gourd cut in half. In the middle was a newborn child, crying and crying.

With delicate paternal tenderness, that gentleman lifted the child up, carried it, and took it to his wife to nurse it. But since the lady had no children, she did not know how to care for him. And she had also been very surprised that a child was born from a pumpkin.

Many people attracted by the great news began to gather at the family home.

The child cried and cried, and some women offered him their breasts to suckle. But the child did not want to suck. And he kept crying and crying. They looked for many ways to feed him so that he would stop crying. But the child resisted, and he kept crying.

Then they infused him with copal and that was how he fell asleep. And from there, every time she cried they put copal on her.

And so, that child who never wanted chichi grew little by little and soon, like everyone else, he began to walk. Since his parents loved him very much, they sent the boy to school. But at school he became very rebellious and very bully.

And then the man thought of baptizing him, and that his godfather would be the priest to pour him holy water. Let’s see if that’s how he composed himself, being in the house of God.

So they did. But the boy was still just as bad and mischievous. He only liked to go to the stream to bathe. And when he played with the water, the water grew and grew, and that was what he liked the most. That’s why, when he went to school, he’d better go to the river. And there was a day when he went with his companions, when they were all in the river, he began to play with the water, and the water grew and grew and his companions drowned.

Then the parents of the drowned children got very angry and went to claim the priest and the gentlemen who were his parents. But what could they do to Juan, if he was a creature. The most they did was scold him. But no matter how much they scolded him, he was as if nothing had happened.

Then his father, seeing that Juan didn’t care about everything, got angry and said:

Well, if you’re happier in the river than at home, go live by the river!

Then Juan said to his godfather:

–If what they want is for me to leave, then yes, I’m leaving. I just want to ask you a great favor: give me a cane for the road.

The priest gave him the cane, and the boy, walking, got into the water, and a great whirlpool was made, and a great noise was heard, until it disappeared. And in the water he made his house. That is why every June twenty-fourth it rains a lot, and there is a lot of thunder, because it is the day of San Juan, and that day the force and command that he has over the sea, which was his house, is heard.

Nahuatl version

SAINT JOHN

Ni eliaya se tetata uan se tenana, tlen ax

kipiyayaj ininkoneuaj, pero ni tlakatl tekitiya-

ya tlauel; uan tiempo de tokistlaj kitoojki

ayojtli, pero ni ayojtli san mopachanik san

mopachanik uan ax tlakiyaya; asta kej tlajki

setsij, uankinoj nopa iteko ax kanaj kinejki

kitekis pampa tlauel setsij; kikauilik machi-

kauia kuali, uan panok tonatij, nopa ayojtli

kimokuitlauiyaya kimokuitlauiyaya tlauel,

pampa eltoya ueyi uan kuaueueyak; pero se

kualkaj yajki tlachiato imilaj, kiitato nopa

ayojtli kuitlatsiyantok, uan de nopanoj uets-

tok se pilkonetsij, se pilokichpiltsij tsajtsiti-

kaj… momajmatik, pero ika maluili kitlalantej-

ki kiuikak para ichaj, para makichichiti isiuaj,

pero komo isiuaj ax kipiyaya ikoneuaj, ax

kimatki kenijkatsaj kichiuas, uan ijkinoj, asi-

koj miak gentes ipan nopa kali, pampa kima-

tijkej para nopa tlakatl kiasitok se okichpiltsij

ipan imilaj, uan nopa konetl pejki choka uan

choka… ax kinekiyaya moseseltis, kimaka-

yayaj ininchichi sekijnok siuamej uan ax tlen

kinejki, uan ya kimakaj choka; tlemach ki-

chiuilijkej uan ax tlen kinejki; asta kej solo

kikopaluijkej, uankinoj kena kochki nopa okich-

piltsij, uan cada vez kemaj kinekiyaya chokas,

san ya kichiuiliyayaj, ya kochiyaya; pero

komo nochi cristianos, ni okichpiltsij ya ika

inoj moskaltik, nimaj pejki nejnemi; itatauaj

nimaj kitlalijkej ipan escuela, pero ipan es-

cuela, tlauel mokuapki mosisinijketl, uan tla-

teuijketl, uankinoj lo he tlen kichijkej itatauaj

mejor kipensarojkej para mejor kikuaaltisej,

uankinoj kikamauijkej totajtsij, para ya ma-

kikuaateki haber tlaj ika ijkinoj mokualtilis

kentsij, jaaaj!, pero Juantsij kiseguirok igual,

ya solo kinekiyaya yas atenoj; kemaj ya youi-

yaya escuela solo nopanoj solo nopanoj youi-

yaya atenoj o atlajko; kemaj youiyaya escue-

la kinkuiteuiyaya icompañeros uan youiya-

ya nopa atlajko, uan kemaj ya kalaktokej

atlajko, ya peuayaya kiauiltia atl, uan nopa

atl posoniyaya, uan se ueltaj kintlami ami-

sauik icompañeros; initatauaj nopa konemej

kiajuatoj nopa itata Juantsij, pero tlen ijki

kiijlis ya, ikonej uan ya kuekuetsij; solo san

kuali kiajuak uan kuali kiajuak –kiijli–

“uan ijkinoj”, kiijtojki Juan, “si tlaj ax inkine-

kij inechitasej nikanij” –kiijtojki– mejor

nias, ¡aaaj! “kiijtojki nopa tetata; “kena”,

kiijtojki, “ax tijneki ax tijneki tiitstos nikaj

kalijtik; tlaj tijneki tiitstos mas ne atlajko’

–kiijli– “pos nepa mejor xiitstoti” – “pos

kena nias, san nomas nikijlis notiotaj ma-

nechmaka no bastón”. Uan nelia nopa totajtsij

kimakak ibastón San Juan, yajki kikonanki

iojui; kalakito ipan atl uan ika nopa ibastón

pejki komo kikuaneloua uan nimajantsij pejki

posoni uan pejki tlatomoni, nopa atl komo

kej mosisinik uan kej atsompoliuito; uan ye-

ka namaj ipan cada veinticuatro de junio

tlauel tlauitekij, tlauel tlatomoni, tlauel tla-

petlani; pampa nopanoj tlanauatia yaya nopa

San Juan; pampa nopanoj mochantito.

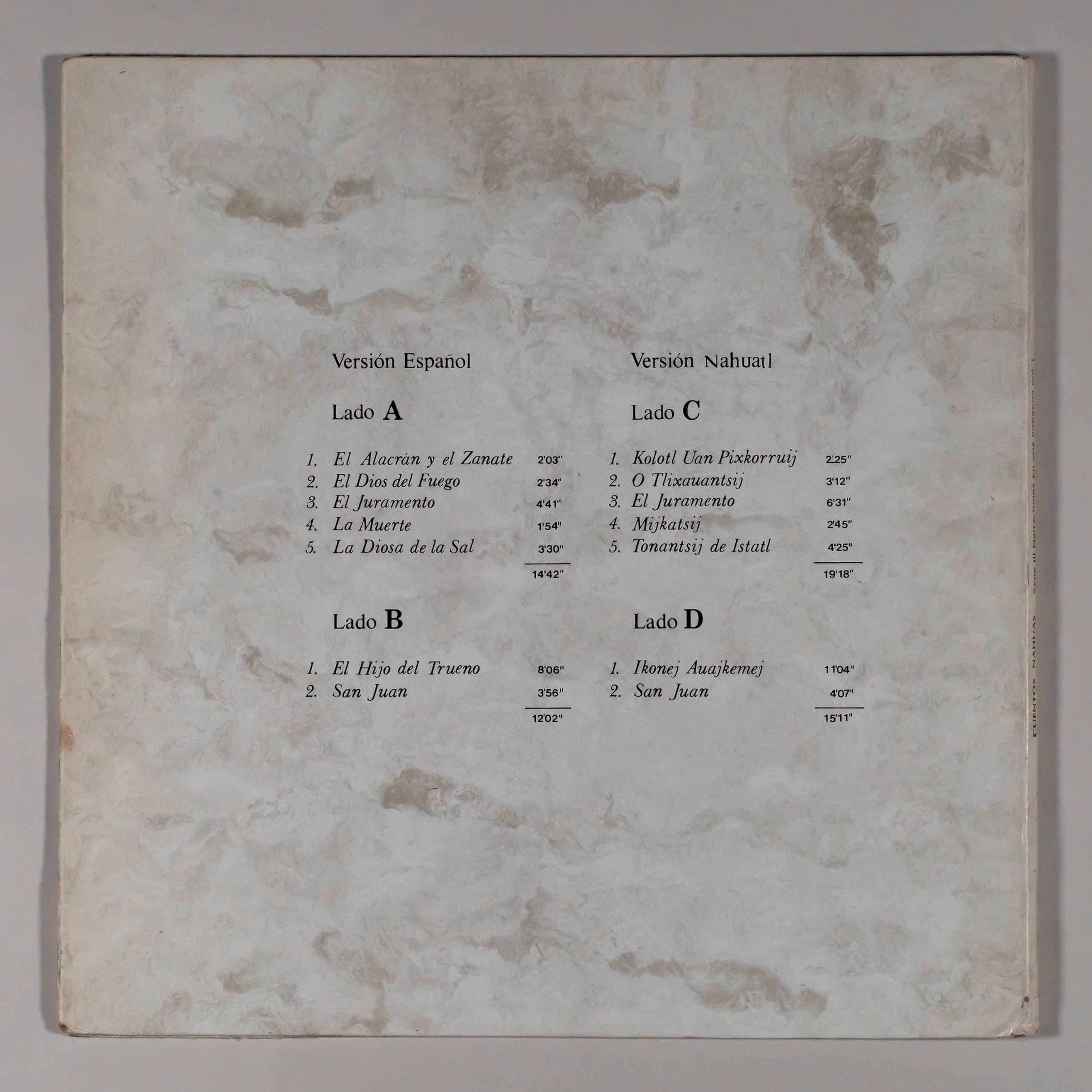

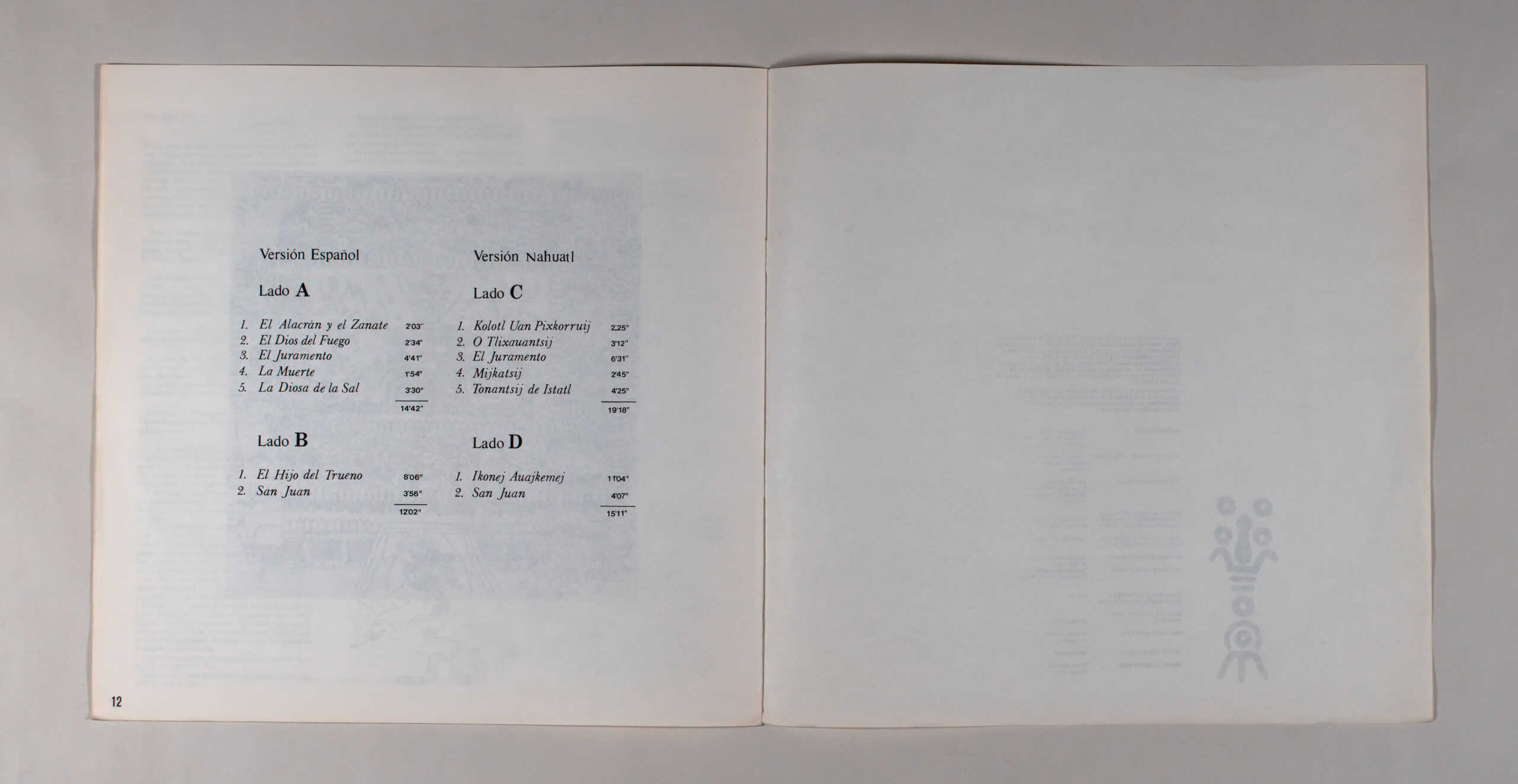

Spanish version

Side A

- The Scorpion and the Grackle 2’03”

- The God of Fire 2’34”

- The Oath 4’41”

- Death 1’54”

- The Goddess of Salt 3’30”

Side B

- The Son of Thunder 8’06”

- Saint John 3’56”

Nahuatl version

Side C

- Kolotl Uan Pixkorruij 2’25”

- O Tlixauantsij 3’12”

- The Oath 6’31”

- Mijkatsij 2’45”

- Tonantsij from Istatl 4’25”

Side D

- Ikonej Auajkemej 11’04”

- Saint John 4’07”

THE RESEARCH TASKS AND COLLECTION OF MATERIALS THAT MADE THE REALIZATION OF THIS ALBUM POSSIBLE WERE ACHIEVED THANKS TO MRS. CARMEN ROMANO DE LOPEZ PORTILLO PRESIDENT OF THE NATIONAL FUND FOR SOCIAL ACTIVITIES (FONAPAS), FOR THE FINANCING GRANTED TO THE AUDIOVISUAL ETHNOGRAPHIC ARCHIVE OF THE NATIONAL INDIAN INSTITUTE WITHIN THE OLLIN YOLIZTLI PROGRAM.

THE EDITION OF THESE CULTURAL REVALUATION MATERIALS WAS ALSO COVERED WITH THE GENEROUS FINANCIAL CONTRIBUTION OF VARIOUS TRADE UNIONS.

ALFRED ELIAS

Director of the National Fund for Social Activities

IGNACIO OVALLE FERNANDEZ

General Director of the National Indigenous Institute

JOHN CARLOS COLIN

Head of the Audiovisual Ethnographic Archive of the National Indigenous Institute

ANGEL AGUSTIN PIMENTEL

J. JESUS HERRERA PIMENTEL

ALEJANDRO MENDEZ ROJAS

Ethnomusicology Unit

ANGEL AGUSTIN PIMENTEL

ALEJANDRO MENDEZ ROJAS

field recording

Bonifacio Hernandez

Informant and Narrator in Nahuatl

ERNESTO GOMEZ CRUZ

Narrator in Spanish (Courtesy of Discos Peerless)

JESUS SANCHEZ PADILLA

ALEJANDRO MENDEZ ROJAS

Edition

MARTHA COVARRUBIAS NEWTON

Graphic design

ORLANDO GUILLEN

Literary version in Spanish

PROF. PEDRO OLEA

Introduction

PROF. GILBERTO DIAZ

Transcription and Translation

Tracklist:

NAHUA TALES

SPANISH VERSION

SIDE 1

- A1 The Scorpion and the Grackle 2:03

Performer(s): Ernesto Gomez Cruz

- A2 The God of Fire 2:34

Performer(s): Ernesto Gomez Cruz - A3 The Oath 4:41

Performer(s): Ernesto Gomez Cruz - A4 Death 1:54

Performer(s): Ernesto Gomez Cruz - A5 The Goddess of Salt 3:30

Performer(s): Ernesto Gomez Cruz

SIDE 2

- B1 The Son of Thunder 8:06

Performer(s): Ernesto Gomez Cruz - B2 St. John 3:56

Performer(s): Ernesto Gomez Cruz

NAHUATL VERSION

SIDE 3

- C1 Kolotl Uan Pixkorruij 2:25

Performer(s): Bonifacio Hernández - C2 O Tlixauantsij 3:12

Performer(s): Bonifacio Hernández - C3 The Oath 6:31

Performer(s): Bonifacio Hernández - C4 Mijkatsij 2:45

Performer(s): Bonifacio Hernández - C5 Tonantsij from Istatl 4:25

Performer(s): Bonifacio Hernández

SIDE 4

- D1 Ikonej Auajkemej 11:04

Performer(s): Bonifacio Hernández - D2 Saint John 4:07

Performer(s): Bonifacio Hernández

Credits:

Alfredo Elias

Director of the National Fund for Social Activities

Ignacio Ovalle Fernandez

General Director of the National Indigenous Institute

Juan Carlos Colin

Head of the Audiovisual Ethnographic Archive of the National Indigenous Institute

Ángel Agustín Pimentel, J. Jesús Herrera Pimentel and Alejandro Mendez Rojas

Ethnomusicology Unit

Angel Agustin Pimentel and Alejandro N. Mendez Rojas,

Field recording

Jesus Sanchez Padilla

Alexander Mendez Rojas

Edition

Martha Covarrubias Newton

Graphic design

Orlando Guillén

Spanish Literary Version

Prof. Pedro Olea

Introduction

Prof. Gilberto Diaz

Transcription and Translation

Notes:

The research tasks and collection of materials that made the realization of this album possible were achieved thanks to Mrs. Carmen Romano de López Portillo, president of the national fund for social activities (fonapas), for the financing granted to the audiovisual ethnographic archive of the national indigenous institute within the Ollin Yoliztli program.

The edition of these cultural reassessment materials was also covered by the generous economic contribution of various union groups.