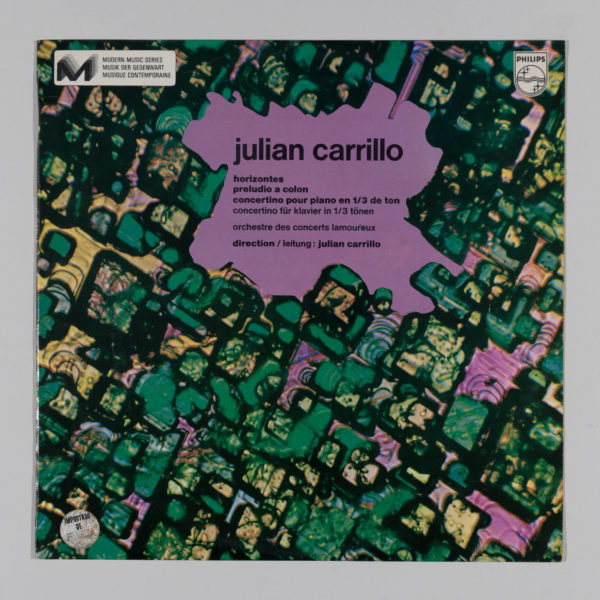

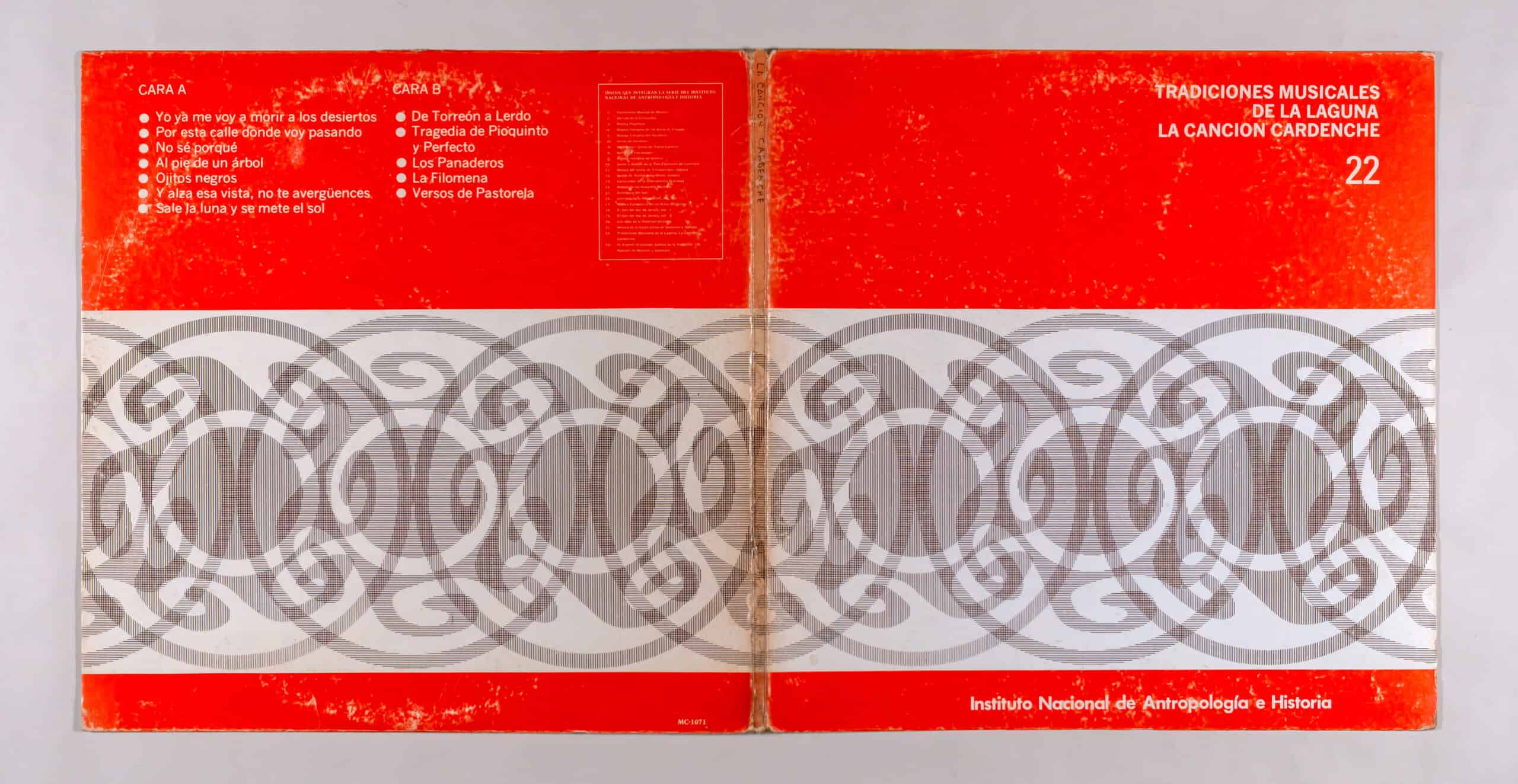

MUSICAL TRADITIONS FROM LA LAGUNA: THE CARDENCHE SONG

INAH SEP

|

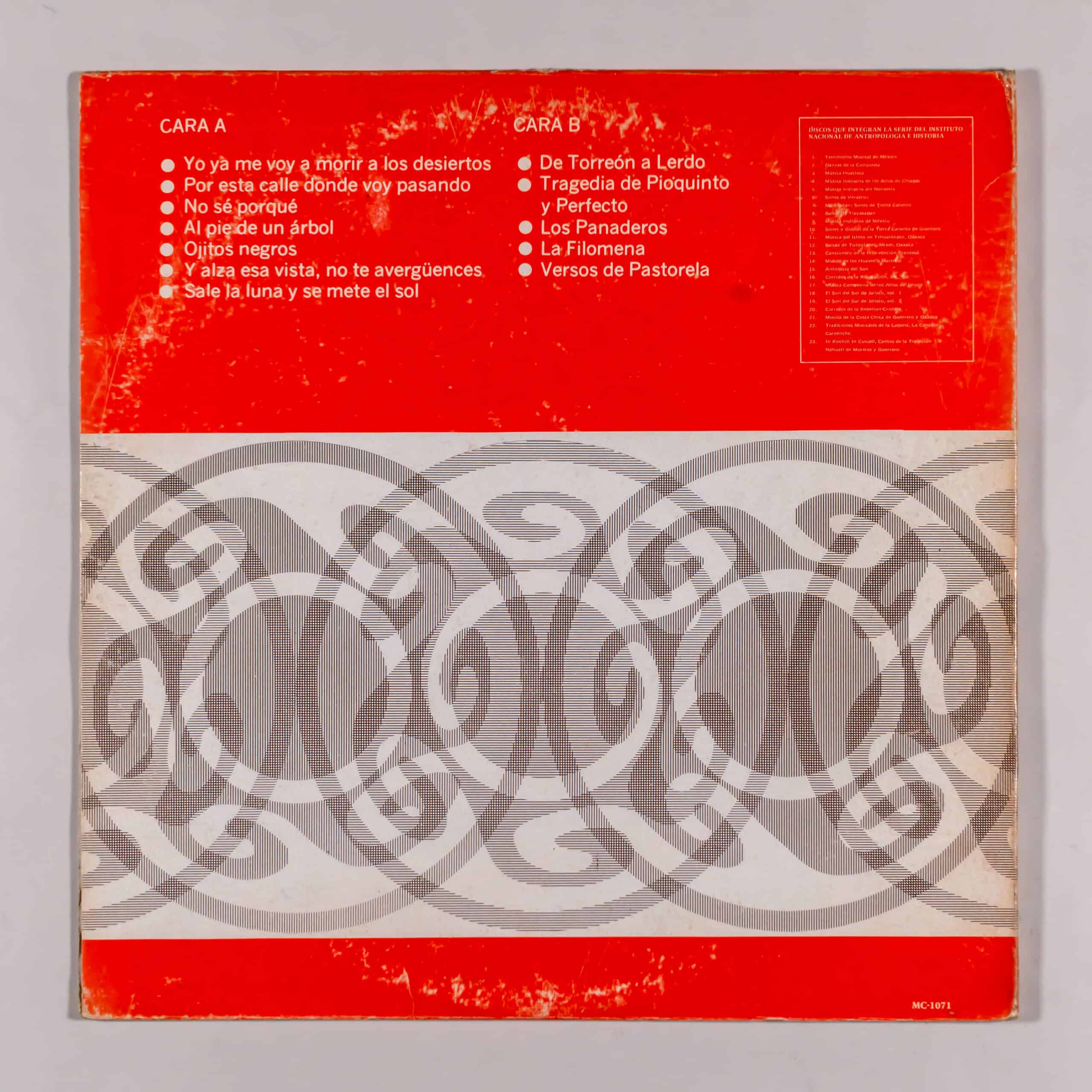

Label: INAH-SEP INAH-22, MC-1071 Released: 1978 |

Country: Mexico |

Info:

MUSICAL TRADITIONS FROM LA LAGUNA: THE CARDENCHE SONG

IRENE VAZQUEZ VALLE

SEP NIAH

National Institute of Anthropology and History

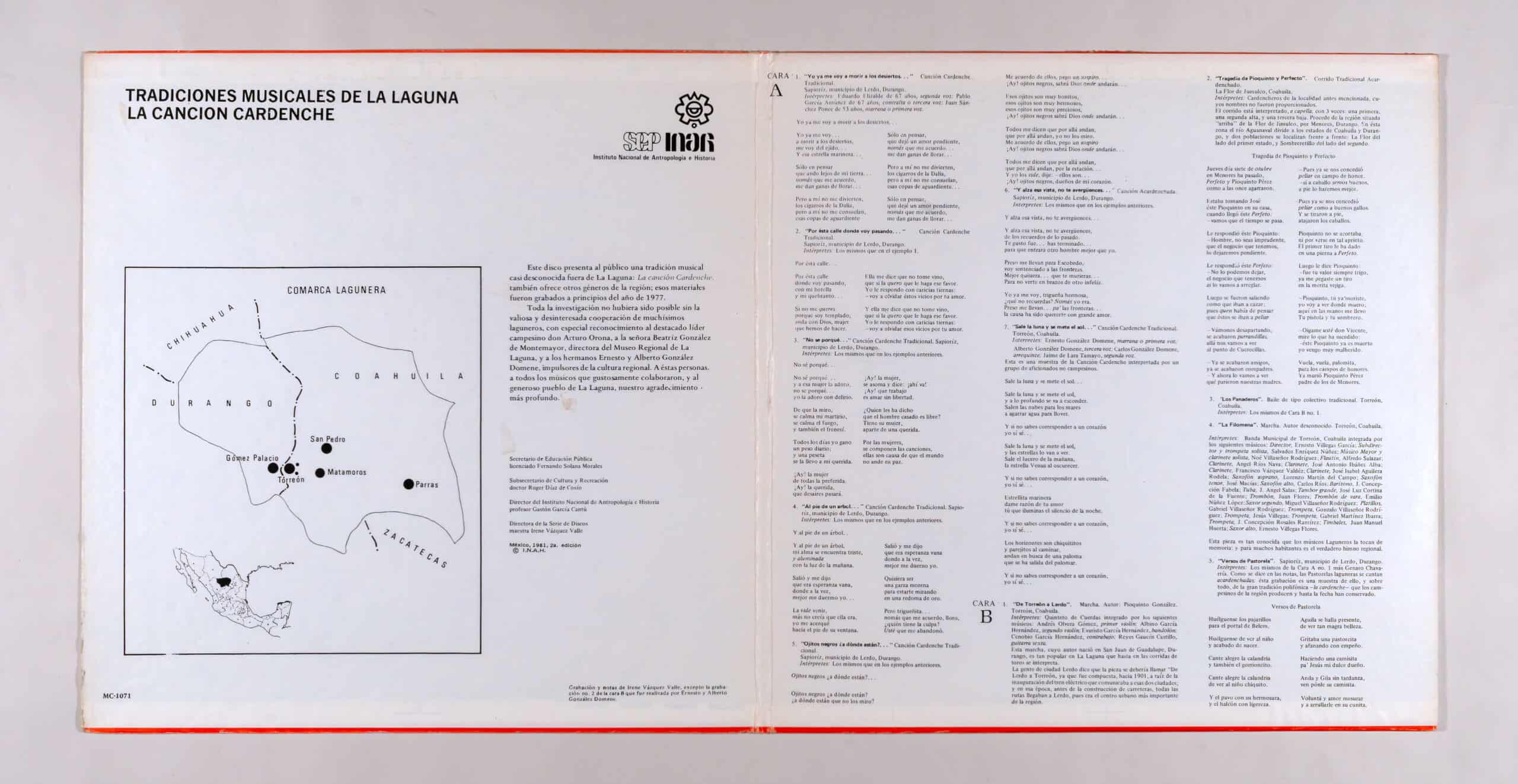

GEOGRAPHICAL DESCRIPTION

La Laguna is located in the extreme southwest and northeast, respectively, of the states of Coahuila and Durango. It has an average altitude of just over 1,000 meters above sea level, and is largely a plain. The main rivers are the Nazas and the Aguanaval; both have a torrential character and constitute a closed basin, since their waters do not have an outlet to the sea. The two rivers fertilize on their way, lands of La Laguna, because they carry organic matter and alluvium; On the other hand, the region has a very deep arable layer and the land, crumbly, is of extraordinary quality. However, the dry and extreme climate, the scant rainfall –which barely throws between 200 and 400 mm per year–, and the evaporation that is 11 times greater than the rainfall, mean that La Laguna, eminently agricultural, can only subsist thanks to irrigation. .

The flora and fauna are the same as those found in most of the semi-desert areas of the great Mexican highlands; for this reason, deer, hares, rabbits, snakes and numerous birds are original inhabitants of the region; In the same way, the gobernadora chaparral, the hojasén, the huizache, the blinding nopal, the cactus, the lechuguilla and the cardenche, among others, are plants that make up the lagoon landscape.

BRIEF HISTORICAL REVIEW

At the time of the Conquest, the current Comarca Lagunera was inhabited by the Irritilas, a tribe of hunter-gatherers divided into clans. These lagoon inhabitants had the Zacatecos and Tamazultecos as neighbors, both sedentary groups dedicated basically to agriculture. For their part, the Irritilas lived from fishing on the banks of the Nazas and Aguanaval rivers and from the Mayrán and Viesca lagoons, as well as from the crops grown in the lowlands of these rivers and from harvesting. Their existence was semi-nomadic with temporary establishments that depended, given the semi-desert character of the region, on springs, rivers, streams and permanent watering holes.

The definitive attempt of Spanish penetration and settlement in the territory of the Irritilas was carried out by the Jesuits in the final years of the 16th century, helped by people from Tlaxcala.

At the end of the 16th century, La Laguna –belonging ecclesiastical to the bishopric of Guadalajara, and politically and administratively to Nueva Vizcaya–, was beginning a new stage. As far as population is concerned, Spaniards and Tlaxcalan horticulturists managed to settle at the cost of the sharp reduction of the natives. However, during the 17th century, the new population did not prosper, basically due to the following factors: the constant attacks of the nomadic Indians, the new diseases, the resistance of the natives to congregate in towns, and the incipient development of the cattle ranch.

During the 17th and 18th centuries, the characteristic of La Laguna was the use of the land for cattle raising developed in large estates. This type of land use further disrupted the lives of the original inhabitants of this and surrounding regions, since on the one hand it reduced their natural resources by being evicted from their travel territories, and on the other hand, the destruction of the buffalo herds to take advantage of only the skins and tallow, determined to a large extent the aggressions of neighboring groups that tried to make up for the loss of the Cíbola cattle, their main food resource, with Spanish cattle, particularly horses, which were widely used both as delicate delicacy that as a horse for their mobilizations.

In the middle of the 19th century, the huge cattle ranches were broken up; multitude of lands were acquired by foreign companies that bought or rented them. Little by little, La Laguna was divided into numerous haciendas and ranches. Despite the fact that the land continued to be owned by few hands, the division brought with it a progressive increase in the population and cereals, cotton and fodder began to be cultivated. In other words, an economic change occurred in the region, since the agricultural era began.

SOCIOECONOMIC OVERVIEW

From the last quarter of the last century, until very recent years, the lands of La Laguna were used mainly for the cultivation of cotton. Until the 30s of our century, the agricultural land of La Laguna was divided, and the owners and tenants were grouped into joint-stock companies; These companies put the land up for auction to farmers who, by working it with the necessary capital, could answer for the lease; They also had all the technology for marketing cotton, and even came to own textile and clothing factories. On the other hand, foreign loan banks had also been established for cultivation, which later intervened in the harvest to collect their investments. This means that the land-owning companies and the banks had the entire regional production process in their hands and that no small farmer could compete with them. At this time, a vast and efficient -although not equitable- network of canals for the use of irrigation water was built. This network was established by the drilling of wells equipped with electric pumping machinery.

The agricultural era of cotton, also boosted by the growth of urban centers and communication routes, especially railways, which connected the region with the center of the country, the main market for yarns and textiles, attracted a large working population to La Laguna. and peasant woman who took root and multiplied. In the countryside, all this growing labor force was divided into two categories: those who had permanent employment on the haciendas and ranches, who had a secure home and sustenance, and who formed small groups, and the other category that was represented by all the people who had temporary employment, hired during the irrigation and harvest season, without a permanent home and who formed the vast majority.

Starting in the second decade of our century, strong capital was invested again in La Laguna; this time they were earmarked for the introduction of modern agricultural machinery that reduced the costs of growing and marketing cotton. Along with the above, the hacendados took measures to expel from the towns of the haciendas and ranches all the peasants who did not have a permanent job, who were not “casillados”.

The expulsions, and the poor general conditions of the agricultural workers forced them to organize and exert pressure through strikes, which became more and more frequent, until, in 1936, a general strike broke out to obtain the collective contract that implied a series of requests among which are: reduction of the working day, increase of wages and rest of the seventh day.

However, the refusal of tenants and landowners to improve working conditions, and government support for peasant organizations contributed to the latter changing their goals: instead of better working conditions, the distribution of large farms among peasants without Earth.

With the agrarian distribution begun in 1936 by the Cardenista regime, the distribution of land and water in La Laguna became more equitable, at least in intention.

Due to the cost of the technology required for cotton, the main crop in La Laguna, the new endowments of ejido lands were made collectively. It was thought that it was profitable to organize the purchases of machinery necessary for the entire marketing process of agricultural products in a collective way, for this, the federal government granted official credit, rearranged the provision of water, undertook irrigation works. Despite the good intentions, over time the official credit collective societies were subdivided into small groups, until today, the atomization of the ejido plot is the most frequent, and the operation of the collective ejido is rare. The reasons for the failure of collectivization were very complex, but the following can be mentioned: corruption in the credit system and official provision, lack of politicization in the collective groups and, subjugation, due to better economic conditions, of the agricultural land owned by private.

Currently, the so-called small property is the most successful economic form in La Laguna, that is, it has a more productive and diversified agriculture; and this, in part, thanks to the drilling of wells, which 60% cover the water needs of agricultural land.

However, the extraction of subsoil water has brought about new and serious problems, among them are the following: annually the extraction exceeds by a considerable margin the natural recovery of the groundwater tables, the cost of water from the waterwheel is constantly increasing, for this reason , and due to a lack of credit support, few ejidatarios and small owners can improve the conditions of their crops. All of the above shows that in La Laguna water determines agriculture (their main livelihood), the extension of crops, the type of them, and ultimately the number of people who can live with the minimum conditions necessary in the region.

MUSICAL TRADITIONS OF LA LAGUNA

Those associated with religious manifestations

A panoramic review of the most relevant traditions cannot fail to include the Colloquios and the Pastorelas. The first are religious representations interpreted in honor of a certain Saint; For example, one dedicated to San Isidro, the main patron of La Laguna, and another to the Holy Kings were interpreted. This genre, almost extinct in the region, was completely sung. For their part, the Pastorelas, which are still represented, have “their part of story and their part of song.” They are generally performed on December 24 and 25, and on January 6, although in the region it is said that they used to be seen, until very recently, on February 2. The characters involved in this genre are the same ones included in other regions of the country that maintained or maintain this tradition. Its singularity lies in the way of interpreting “the sung part”, since in La Laguna it is done with 4 voices that are combined in a polyphonic way, without any instrumental accompaniment, and in a cardinal style, a style that will be explained later.

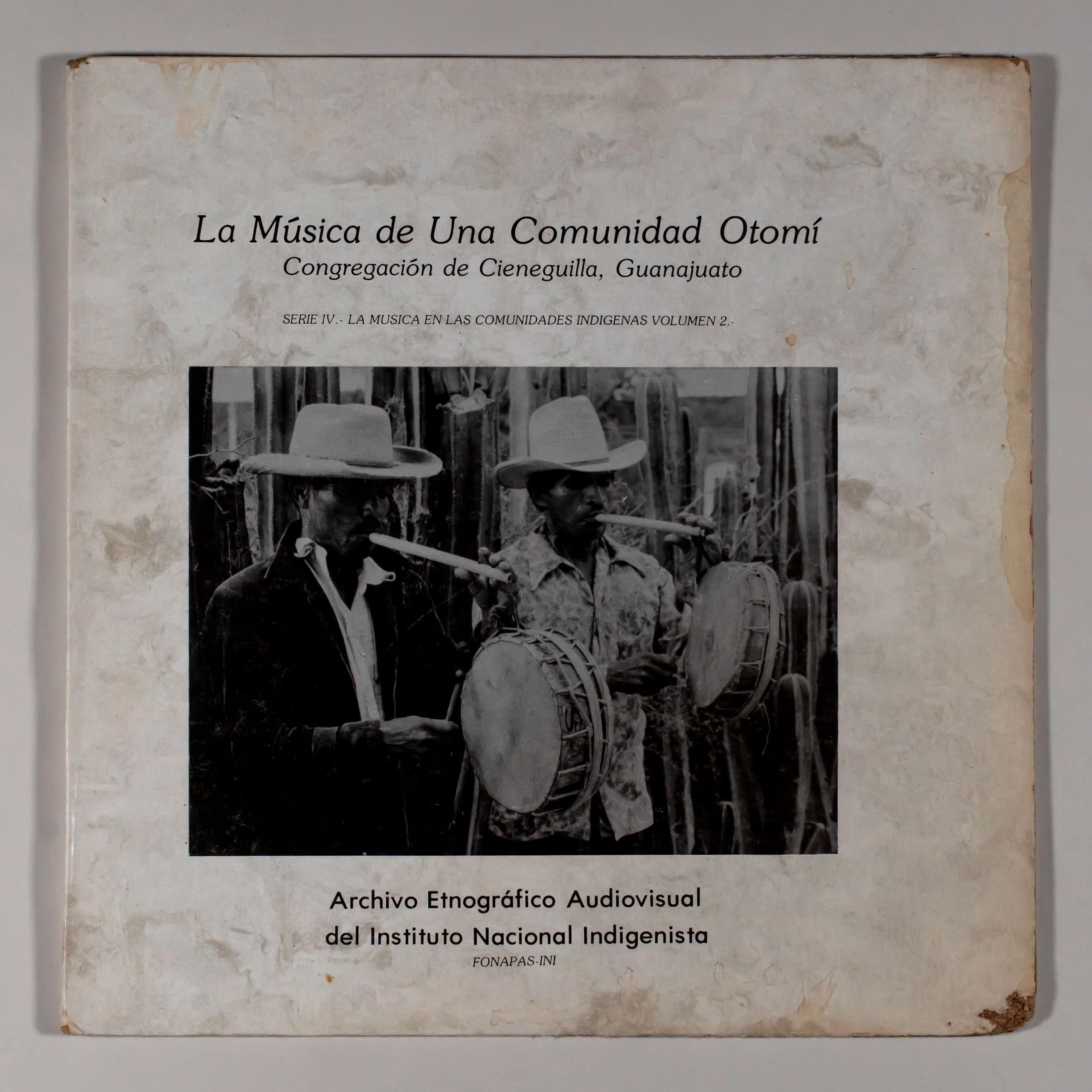

In addition to performances, various dances associated with religious festivities are practiced in the region. Among the most widespread is that of Matachines -which perhaps has its origin in the colonial period-, since all those in this cycle date from that time. Previously the dancers of this dance covered their faces with rows of beads; Not anymore, but they still wear a red skirt adorned with reeds and pierced peach seeds. The Matachines accompany themselves with a reed flute and a large “tambora” with two heads that hangs from the neck and shoulder, and is played with a vaquetón.

Another dance that is practiced in the region is that of La Pluma or La Conquista. This dance is essential in the festival of the patron saint of La Laguna, San Isidro Labrador. In it, as in all those of that cycle, “El Cortés” intervenes as the main characters. “La Malinche” and “El Monarca”; In addition to these, all the dancers who, in rows, stand behind the “Cortes” or the “Monarch” are counted. The dancers do not have special clothing, although they carry a feather fan in their right hand. The dance of La Pluma is accompanied by a violin and a tambora; the music is made up of several “sones” for the different evolutions of the “danzantes”.

In addition to the aforementioned dances, the following were practiced in the region until very recent times: Morismas, Paloteadas, Rattles, Arcos, and La Danza del Indio.

Non-religious musical traditions

Dances of Couples. By mentions of old locals, both musicians and people belonging to different professions and social status, also by printed repertoires and manuscripts of pieces for piano, for small orchestras, and bands, as well as by some newspaper news, it can be affirmed that there were dances singles of mixed couples and dance-games of a collective type that were widely accepted in the region. Among the latter are the following: Las Cuadrillas and Los Panaderos (The bakers). The dance of the bakers, of a collective type, allowed the game, since the musicians, through the copla, indicated the various actions that the couples should carry out. For its part, the dance-game of the squares, within which the dancers arranged themselves in two separate and facing rows, one for men and the other for women, was directed by a man who held a long stick, which when struck on the floor , pointed out the choreographic changes. The dancers at the ends of the rows – ends called the heads – guided the rest of the participants. The cuadrillas, musically, consisted of various pieces that were played successively; many of them were polkas. A cuadrilla, when the environment favored it, used to last up to 2 hours; however, this dance-game generally consisted of 5 parts, each of which had two or three pieces. As for the loose danceable genres, the following can be listed, which were very popular in the region: Polkas, waltzes. varsovianas, jacks, marches, chotises, masurcas, danzones, dances, gallops, parades and two steps.

Songs. There is a series of traditional songs from the region that come from very different eras; Among them are the following: “The Warsaw”, “The barzon”, “Mama Charlotte”, “The Forsaken”, “The machaquito”, “The dove”, “Carrasco’s Goodbye”, “Alborada”, ” The Willow and the Palm” In addition to those mentioned, various zarzuela songs were very popular, as well as various little sonnets and satirical songs, although the most liked were romantic songs composed locally, and others that were known throughout the Republic. Towards the 1920s, many songs that were known in wide regions of the country became popular; many of them came from the mouths of the “bonanceros”, the migrant workers who came to the pinch and who came from various states.

Romances and Corridos. These genres are very popular in the region. Among the Romances that are known are two of the most widespread in the country: That of “Doña Elena”, and “The Delgadina”. During the Mexican Revolution, La Laguna produced many Corridos –Tragedias they are called–, like so many other regions of the country, among the best known of local production the following can be mentioned: “The Battles of Torreón”, “Departure of the gachupines from the city of Torreón”, “Of the Taking of San Pedro”, etc. Many corridos that come from other regions are also sung; some of them were brought to the region “by those of the theater”, others circulated in the mouths of the troops that militated in the different sides in conflict of those so violent years.

Musical instruments used in the region

As solo instruments, the most used in the region were the following: harp, violin, 6th guitar, harmonica, concertina -small accordion- the large drum called tambora, and the triangle, which, like the drum, is used as accompaniment. rhythmic. In the small towns the cylinder was sometimes heard, called in the region “celestine”…

The harp was used as an accompaniment to the song, and apparently it came from Zacatecas; This instrument was used above all by the “singers” who from town to town spread tragedies with local or national themes, the old Romances, and romantic and satirical songs. Nowadays, the harp has been replaced by the 6th guitar, as the instrument preferred by popular performers, although until a few years ago it was not uncommon to hear the two instruments together accompanying the voice. The use of the 6th guitar, used in La Laguna, has a peculiarity: the extended use of the metal strings and the plectrum or nail, placed on the thumb.

Another widespread instrument is the violin, which has been essential to accompany “sones de danzas” and syrups.

Instrumental ensembles.

Nowadays, the instrumental ensemble called the pitacoches, more widely known as the “northern accordion ensemble”, dominates the entire region. However, until very recent times for the dances of the ranches a clarinet, the harp and the violin, or the violin and the accordion were used; although in the “good dances” the pieces were accompanied by an orchestra or a band. In addition to the aforementioned ensembles, the typical ones and the string quintets were widely accepted.

In the 3 cities –Lerdo, Gómez Palacio and Torreón–, centers of economic activity in La Laguna, the tradition of the brass band supported by the Municipality has been maintained. The tradition of string quintets has also been continued; there is, for example, the “Club Verde” Quintet that plays in various parts of that city, and is located in a cantina in Gómez Palacio that bears the same name as the Quintet; There is also another Quintet in Torreón that, like the one mentioned above, plays in a cantina, the one made up of the García brothers, maestro Olvera and maestro Gaucín. These quintets have the following instrumentation: 2 violins, a double bass, a bandolón and a 6a guitar. The bandolón is a string instrument in the shape of a paunchy guitar, with 6 triple strings, all made of steel, played with a pick. The guitar 6a. which includes the lagoon quintets shares the regional tradition of being used with steel strings and played with a fingernail or plectrum. It is worth noting that the quintets play lyrically, and that a part of the bands’ repertoire is also played in this way.

THE CARDENCHE SONG

The name of this genus is the same as that of a very thorny cactus that is part of the region’s flora, and that, despite its rough appearance, is said to be “full of water” inside.

The cardenche songs are also called “garbage dump”, since those who sang them used to do it on top of the hacienda garbage cans, which were sometimes higher than the houses.

This genre is of eminently peasant origin; in La Laguna it was interpreted by and for the laborers; At present, this tradition is preserved precisely by the former laborers and current ejidatarios, and also by landless agricultural workers.

The oral information collected establishes that the cardenche song was already heard, at least, since the end of the last century, and that it was maintained as a tradition in all the lagoon communities. There are those who say that this genre was born in Flor de Jimulco – a town located on the Coahuila side, on the Aguanaval, precisely in the place where this river divides the aforementioned state and Durango. However, many other people affirm that the genus goes beyond La Laguna and that it also exists in other parts of the states of Durango, Coahuila and Zacatecas. It is added that the cardenche song, as a tradition, was still alive and flourishing in the 1930s. At present the genre is being lost as it is practiced almost exclusively by people who exceed half a century. On the other hand, it is very possible that the confluence in the region of people coming from very diverse and sometimes distant places, has provided the genre with various influences; Well, we must not forget that La Laguna mestizo was populated very slowly.

This genre has been so deeply rooted in the region that it has scarred others. That is to say, genres such as the Corrido, the so-called Mexican Song and the songs of Pastorelas lost their own style to adopt in the region, that of the cardenche.

The cardenche song is a polyphonic genre that is always sung in 3 or 4 different voices and a cappella. It is said that in past times it was sung with 5 voices. The groups of cardencheros distribute the voices according to their range. Each of the voices has a popular name; thus, those who sing the lowest voice –called in the region the fundamental–, are known as those who make the marrana or the drag. Another voice, the highest pitched in the ensemble, is known by the name of the contralta, sometimes also called arrequinte or requinto. It is said that the requinto is used above all in Pastorelas songs, and in this case it represents the fourth voice, even higher than the contralta. It is added that when the fourth voice does not exist, the third, that is to say the contralta, takes its place. Another voice is the second, middle voice that frequently carries the melody. third, that is to say the contralta, takes its place. Another voice is the second, middle voice that frequently carries the melody.

The way of playing with the 3 voices differs from one interpretation to another, although according to the cardencheros the biggest changes occur in the sow that, depending on the song, enters before or after the other voices. It is also said that there are songs that “need” to start with the contralta, or with the second voice, while there are others that “must” alternate the contralta and the second voice. It is also said that in the past the contralta was the voice that carried the melody and sang the “verses” of the song, while the other voices only made sounds that served as harmonic accompaniment. It is also said that this happened when very large groups of cardencheros were able to gather.

The current custodians of the tradition, the old peasants, current ejidatarios and former hacienda laborers, keep the lyrics of cardenches in notebooks, since the melody and ornaments of the different voices are preserved in their memory.

The peasants who liked to get together to sing cardenches – that is, the cardencheros – did so every afternoon and evening “after work”. It is said that it was quite an event to listen to them at the time of the cotton picking, when some of the “bonanceros” who came to it also joined the group, and all the other workers listened while playing cards; at this time it was common for him to have a “little drink” to tone the voices.

The cardenche song almost always has a lyrical-love letter, although from time to time it includes in the repertoire, thematic of double meaning, “picosa”, as they say in the region.

Another characteristic of this genre is the inclusion of silences, sometimes quite long, that are inserted throughout each performance; these silences generally do not fall at the end of a melodic phrase or a couplet, on the contrary, they occur in the middle, interrupting the lyrical musical discourse. Such a feature gives great emotionality to the genre.

MUSICAL CONTENT OF THE CARDENCHE SONG

Roberto Portillo

The finding, within our popular traditions, of a form that can be called without a doubt polyphonic, will call the attention and interest of musicologists, anthropologists, historians… and the general public.

The importance of this encounter with the polymelody in a popular context, specifically peasant, suggests the high development that popular manifestations reached in colonial times and is one more example of the capacity for assimilation and artistic expression of Mexicans.

Interpreting polyphony or polymelody requires the skill provided by the trade, and this is only obtained with the combination of experience and ability. The case of the musician whose specialty is singing in poly-melodic choirs is not common, even though he is from an academy. Well, it is rarer to find musicians dedicated to traditional popular manifestations, with that skill and facility to play a second, third or fourth voice.

The interpreters, in the case of the cardenche song, are not limited to the brief execution of one of the voices; they also flaunt a rich knowledge and spontaneity in the ornamentation of the time that corresponds to them.

Due to the characteristics that we will say later, we can anticipate that we are facing an evident testimony of MEXICAN POPULAR POLYPHONY.

Essential detuning

In the recordings it can be noticed that the pitch of the sounds sometimes varies to the point of reaching a slight detuning. The performers perform their melodies to the best of their ability, but for various reasons – old age, illness, the natural exhaustion on returning from work, etc. – they do not achieve the precision that a well-tuned instrument can achieve. However, that characteristic so common in other of our popular genres, that essential detuning, makes it possible to identify (in most cases) authentic regional music.

Characteristics and influences

Once the polyphony is recognized, the first characteristic that stands out in the recordings is the lack of instrumental accompaniment. The slow weather is also noticeable, a reflection of the long sunny days and the great spaces that the earth offers to the eye, the body and the spirit. The solemn character, sometimes passionate, other times religious, and always emotional, provokes subtle contrasts that satisfy the demanding music lover.

The great silences that separate each phrase are determined by the mood and the circumstances in which the performers find themselves, however, those are an integral part of the characteristics of the cardenche song.

Another very important feature is the appearance of the FABORDON. M. Brenet in his music dictionary (Barcelona 1962), tells us:… “The meaning of this name must have come from the substitution of a higher voice than that of the tenor, which would be designated as false, as a characteristic of a false bass (FAUX-BOURDON) transposed to the soprano. Other authors have thought they found the etymological meaning of this word in the presumed use of the falsetto voice for the execution of the upper part of a composition”.

The monk Guillaume speaks of the fabordon as “a manner of the English” who sang it in three voices in sixth chords, with thirds whose starting and ending point always consisted of fifth and eighth chords.

These characteristics of the fabordon, mentioned above, are almost exactly the same as those that appear in the cardenche song, with the exception that the latter can combine up to four voices placed at different heights.

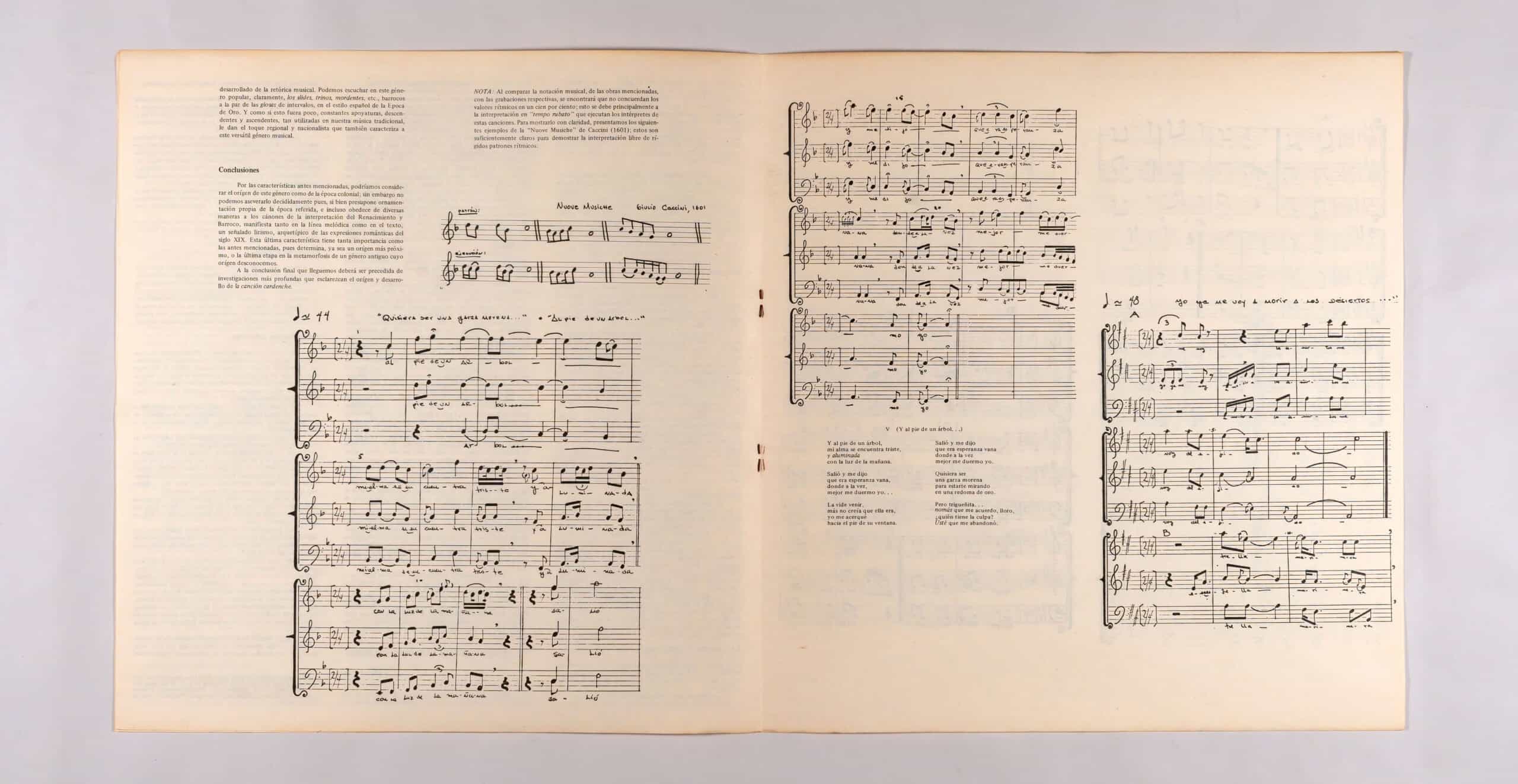

As previously mentioned, the cardenche song has a rich ornamentation in each voice, which essentially belongs to the European Baroque and specifically to the Spanish Renaissance, spanning from the 16th to the 18th century. (–) In the European dances of these centuries, it was common to vary the repetition of each one of the parts, for which it was established to decorate the second time of these dances. Distinguished interpreters, that is, those with the greatest skill, improvised said ornamentation while the others required the Treatises on Gloss and Ornamentation published at the time for this purpose.

The improvisation of the gloss and ornamentation in the cardenche song is very interesting; one can hear that these ornaments are not straightforward, they imply a well-developed empirical knowledge of musical rhetoric. We can clearly hear in this popular genre the baroque slides, trills, mordents, etc. along with interval glosses, in the Spanish style of the Golden Age. And as if this were not enough, constant appoggiatura, descendants and ascendants, so used in our traditional music, give it the regional and nationalist touch that also characterizes this versatile musical genre.

Conclusions

Due to the aforementioned characteristics, we could consider the origin of this genre to be from the colonial era; However, we cannot definitively assert it because, although the period in question presupposes its own ornamentation, and even obeys in various ways the canons of Renaissance and Baroque interpretation, it manifests both in the melodic line and in the text, a marked lyricism, archetypal of the romantic expressions of the 19th century. This last characteristic is as important as the aforementioned ones, since it determines either a closer origin, or the last stage in the metamorphosis of an ancient genus whose origin we do not know.

The final conclusion that we reach must be preceded by deeper investigations that clarify the origin and development of the cardenche song.

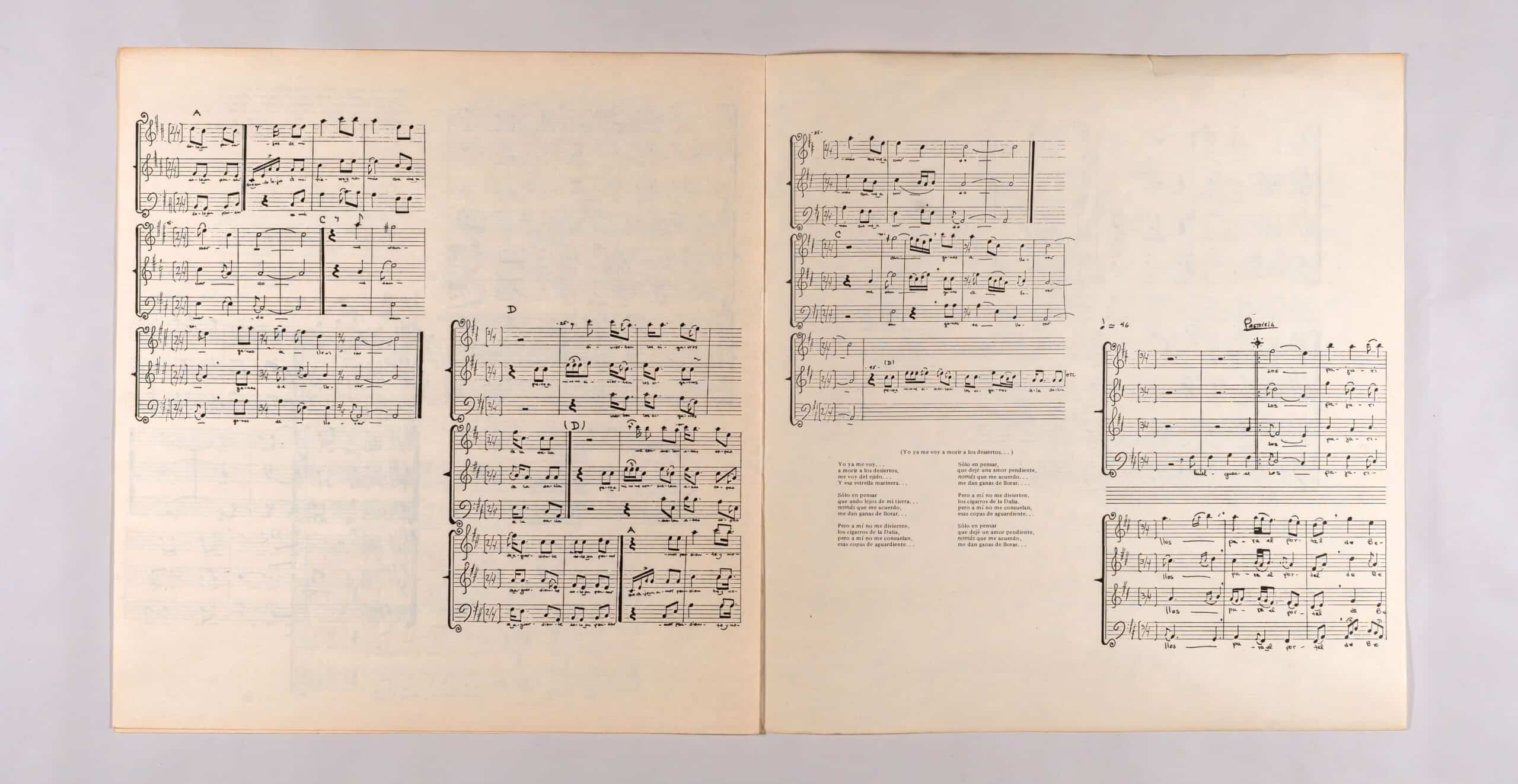

(–) See as an example of a Spanish gloss (in the transcriptions that appear at the end of these notes) Numbers 40 and 21 of the songs “Yo ya me voy…” and “Quisiera ser…” respectively. And as an example of baroque ornamentation 4 and 5 of the “Pastorela” and 21 of “Yo ya me voy…”

NOTE: When comparing the musical notation of the works mentioned, with the respective recordings, it will be found that the rhythmic values do not agree one hundred percent; this is mainly due to the “rubato tempo” interpretation performed by the performers of these songs. To show it clearly, we present the following examples from Caccini’s “Nuove Musiche” (1601); these are clear enough to demonstrate free interpretation of rigid rhythmic patterns:

V (And at the foot of a tree…)

And at the foot of a tree

my soul is sad

and illuminated

with the morning light.

she came out and told me

that it was a vain hope,

where at the same time

I better sleep…

I saw her coming

but I did not believe that she was,

I approached

to the foot of her window.

she came out and told me

it was a vain hope

where at once

I better sleep.

I would like to be

a brown heron

to be looking at you

in a golden vial.

But brunette…

As soon as I remember, I cry

Who is guilty?

You who abandoned me

(I’m going to die in the deserts…)

I’m leaving…

to die in the deserts,

I’m leaving the common…

And that sea star…

Just thinking

that I left a pending love,

I just remember…

It makes me want to cry…

But I don’t have fun

Dalia cigars,

but they do not comfort me,

Those glasses of brandy…

Just thinking

that I left a pending love,

I just remember

makes me want to cry…

But I don’t have fun

Dalia cigars,

but they do not comfort me,

those glasses of brandy…

Just thinking

I’m far from my land…

I just remember

makes me want to cry…

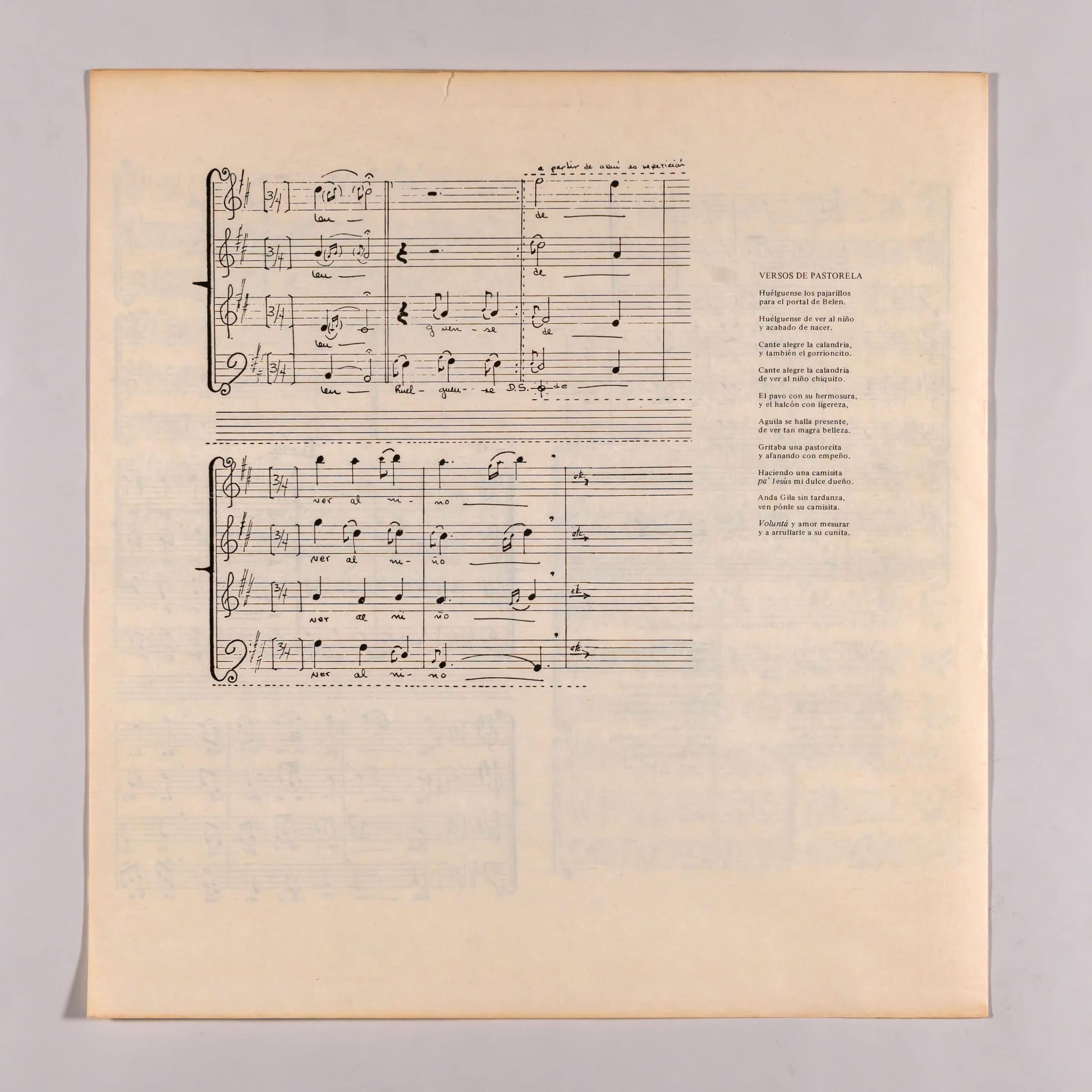

VERSES OF PASTORELLA

Strike the little birds

for the portal of Bethlehem.

Strike to see the child

and just born.

The calandria sing joyfully,

and also the little sparrow.

The calandria sing joyfully

to see the little boy.

The turkey with his beauty,

and the falcon with lightness,

Eagle is present

to see such lean beauty.

A shepherd girl was screaming

and working hard.

Making a shirt

for Jesus my sweet owner.

Go Gila without delay,

come put her shirt on.

Will and love to measure

and to lull her cradle to sleep.

This album presents to the public a musical tradition almost unknown outside of La Laguna: The Cardenche song, also offers other genres from the region; these materials were recorded at the beginning of 1977. All the research would not have been possible without the valuable and disinterested cooperation of many lagoon workers, with special recognition to the prominent peasant leader Mr. Arturo Orona, Mrs. Beatriz González de Montemayor, director of the Museum Regional de La Laguna, and the brothers Ernesto and Alberto González Domene, promoters of regional culture. These people. To all the musicians who gladly collaborated, and to the generous people of La Laguna, our deepest thanks.

Secretary of Public Education

Mr. Fernando Solana Morales

Undersecretary of Culture and Recreation

Doctor Roger Díaz de Cosío

Director of the National Institute of Anthropology and History

Professor Gaston Garcia Cantu

Disc Series Director

teacher Irene Vázquez Valle

Mexico, 1981, 2nd. edition

© N.I.A.H. (National Institute of Anthropology and History)

Recording and notes by Irene Vázquez Valle, except recording no. 2 of side B that was made by Ernesto and Alberto González Domene.

FACE A

1. “I’m going to die in the deserts…” Traditional Cardenche Song.

Sapioriz, municipality of Lerdo, Durango.

Performers: Eduardo Elizalde, 67, second voice: Pablo García Antúnez, 67, contralta or third voice; Juan Sánchez Ponce, 53 years old, sow or first voice.

I’m going to die in the deserts…

I’m leaving…

to die in the deserts,

I’m leaving the common…

And that sea star…

Just thinking

I’m far from my land…

I just remember

makes me want to cry…

But I don’t have fun

Dalia cigars,

but they do not comfort me,

those glasses of brandy.

Just thinking

that I left a pending love,

I just remember…

It makes me want to cry…

But I don’t have fun

Dalia cigars,

but they do not comfort me,

those glasses of brandy…

Just thinking

that I left a pending love,

I just remember

makes me want to cry…

2. “On this street where I am passing…” Traditional Cardenche Song.

Sapioriz, municipality of Lerdo, Durango.

Performers: The same as in example 1.

Down this street…

Down this street

where am I going,

with my bottle

and my broken…

If you don’t love me

because I am temperate,

walk with God, woman

what we have to do

She tells me not to drink wine

that if I love her that I do her that favor.

I answer him with tender caresses:

I will forget these vices for your love.

And she tells me not to drink wine

that if I love her that I do her that favor.

I answer him with tender caresses:

I’m going to forget those vices for your love.

3. “I do not know why…” Traditional Cardenche Song.

Sapioriz, municipality of Lerdo, Durango.

Performers: The same as in the previous examples.

I do not know why…

I do not know why…

And I adore that woman

I do not know why…

I adore her madly.

That I look at her,

my martyrdom calms down,

the fire calms down,

and also the frenzy.

Every day i win

a daily weight;

and a peseta

I take it to my dear.

Oh! The woman

Of all, her favorite.

Oh! The dear,

what a snub will happen.

Oh! The woman,

she leans out and says: there she goes!

Oh! What work

is to love without freedom.

Who told them

that the married man is free?

He has his wife

apart from a loved one.

For the women,

songs are composed

they are the cause of the world

don’t walk in peace.

4. “At the foot of a tree…” Traditional Cardenche Song.

Sapioriz, municipality of Lerdo, Durango.

Performers:The same as in the previous examples.

At the foot of a tree…

And at the foot of a tree

my soul is sad

and illuminated

with the morning light.

She came out and told me

that it was a vain hope,

where at the same time

I better sleep…

I saw her coming

but I did not believe that she was,

I approached

to the foot of her window.

She came out and told me

it was a vain hope

where at the same time

I better sleep.

I would like to be

a brown heron

to be looking at you

in a golden vial.

But brunette…

As soon as I remember, I cry

Who is guilty?

You who abandoned me.

5. “Black eyes, where are they?…” Traditional Cardenche Song.

Sapioriz, municipality of Lerdo, Durango.

Performers: The same as in the previous examples.

Black eyes, where are they?…

Black eyes, where are they?

where are they that I don’t look at them?

I remember them, I take a breath…

Oh! Little black eyes, God knows where they will go…

Those eyes are very pretty

Those eyes are very beautiful

Those eyes are very precious

Oh! Little black eyes God knows where they will go…

Everyone tells me that they are there

They go there, I don’t look at them.

I remember them, I take a breath

Oh! Little black eyes God knows where they will go…

Everyone tells me that they are there

That’s where they go, by the station…

And I saw them, I said: they are…

Oh! Little black eyes, owners of my heart.

6. “And look up, don’t be ashamed…” Cardenchado song.

Sapioriz, municipality of Lerdo, Durango.

Performers: The same as in the previous examples.

And look up, don’t be ashamed…

And look up, don’t be ashamed,

of the memories of the past.

You liked it was… you’re done…

So that another man better than me would enter.

Prisoner they take me to Escobedo.

I am sentenced to the borders.

I would rather… that you die…

To not see you in the arms of another unhappy.

I’m leaving now, beautiful brunette

what don’t you remember? I was just

They take me prisoner… to the borders…

The cause has been to love you with great love.

7. “The moon rises and the sun sets…” Traditional Cardenche Song.

Torreón, Coahuila.

Performers: Ernesto Gonzalez Domene, sow or first voice; Alberto González Domene, third voice; Carlos González Domene, arrequinte; Jaime de Lara Tamayo, second voice.

This is a sample of the Cardenche Song performed by a group of non-farmer fans.

The moon rises and the sun sets…

The moon rises and the sun sets,

and deep down it will hide.

The clouds leave for the seas

to catch water to rain.

And if you don’t know how to correspond to a heart

I know.

The moon rises and the sun sets,

and the stars will see it.

The morning star comes out,

the star Venus at dusk.

And if you don’t know how to correspond to a heart,

I know…

Sailor star

give me reason for your love

you who illuminate the silence of the night.

And if you don’t know how to correspond to a heart,

I know.

The horizons are tiny

and couples when walking,

they are looking for a dove

that has left the dovecote.

And if you don’t know how to correspond to a heart,

I know…

FACE B

1. “From Torreon to Lerdo”. March. Author: Pioquinto González.

Torreon, Coahuila.

Performers:String Quintet made up of the following musicians: Andrés Olvera Gómez, first violin; Albino García Hernández, second violin; Evaristo García Hernández, bandolón; Cenobio García Hernández, double bass; Reyes Gaucín Castillo, sixth guitar.

This march, whose author was born in San Juan de Guadalupe, Durango, is so popular in La Laguna that it is even interpreted in bullfights. The people of Ciudad Lerdo say that the piece should be called “De Lerdo a Torreón”, since it was composed, around 1901, as a result of the inauguration of the electric train that connected those two cities; and at that time, before the construction of highways, all the routes arrived at Lerdo, since it was the most important urban center in the region.

2. “Tragedy of Pioquinto and Perfecto”. Acardenchado Traditional Corrido.

The Flower from Jimulco, Coahuila.

Performers:Cardencheros from the aforementioned locality, whose names were not provided.

The corrido is interpreted, a cappella, with 3 voices: a first, a second high, and a third low. It comes from the region located “above” the Flor de Jimulco, by Menores, Durango. In this area, the Aguanaval River divides the states of Coahuila and Durango, and two populations are located face to face: La Flor on the side of the first state, and Sombreretillo on the side of the second.

Tragedy of Pioquinto and Perfecto

Thursday, October 7

in Minors has passed,

Perfeto and Pioquinto Perez

about eleven o’clock they grabbed.

I was drinking Jose

this Pioquinto in his house,

when this Perfecto arrived:

Come on, time is passing.

This Pioquinto answered him:

“Man, don’t be reckless.

that the business we have,

we will leave it pending.

This Perfect One answered him:

-We can’t leave it.

The business we have

oh we’re going to fix it.

Then they left

like they were going hunting;

Well, who was to think?

That they were going to fight.

-Let’s go dispersing,

no more barbecues,

we will see each other there

to the point of Cuerecillas.

-It’s over, friends.

It’s over mates.

And now we are going to see

What did our mothers give birth to?

“Well, it’s been granted to us.”

Fight on the field of honour.

–If we are good on horseback,

on foot we will do better.

Well, we have already been granted

fight like good roosters.

And they jumped on foot

they stopped the horses.

Pioquinto was not shortened,

nor for being in such a bind.

The first shot has given him

on one leg to Perfecto.

Then Pioquinto tells him:

–was your courage always wheat,

you already shot me

in the worthy bladder.

–Pioquinto, you already died,

I’m going to see where I die;

here in the hands I take

your gun and your hat.

-Listen to me, Don Vicente,

look what happened:

–This Pioquinto is already dead

I come very badly hurt.

Fly, fly, little dove,

for the fields of honors.

Pioquinto Pérez has already died

father of the minors.

3. “The Bakers”. Traditional collective dance.

Torreon, Coahuila.

Performers:The same ones from Cara B no. 1.

4. “Philomena”. March. Unknown author.

Torreon, Coahuila.

Performers:Municipal Band of Torreón, Coahuila made up of the following musicians: Director, Ernesto Villegas García; Subdirector and solo trumpet, Salvador Enríquez Núñez; Major Musician and solo clarinet, Noé Villaseñor Rodríguez; Piccolo, Alfredo Salazar; Clarinet, Ángel Ríos Nava; Clarinet, José Antonio Ibáñez Alba; Clarinet, Francisco Vázquez Valdéz; Clarinet, José Isabel Aguilera Rodela; Soprano saxophone, Lorenzo Martín del Campo; Tenor saxophone, José Macías; Alto saxophone, Carlos Ríos; Baritone, J. Concepción Fabela; Tuba, J. Angel Salas; Big drum, José Luz Cortina de la Fuente; Trombone, Juan Flores; Rod trombone, Emilio Núñez López; Second Saxor, Miguel Villaseñor Rodríguez; Cymbals, Gabriel Villaseñor Rodríguez; Trumpet, Gonzalo Villaseñor Rodríguez: Trumpet, Jesús Villegas; Trumpet, Gabriel Martínez Ibarra; Trumpet, J. Concepción Rosales Ramírez; Timbales, Juan Manuel Huerta; Alto saxor, Ernesto Villegas Flores.

This piece is so well known that Laguneros musicians play it from memory; and for many inhabitants it is the true regional anthem.

5. “Verses of Pastorela”.

Sapioriz, municipality of Lerdo, Durango.

Performers:The same ones from Side A no. 1 more Genaro Chavarria.

As it is said in the notes, the Pastorelas laguneras are sung cardenchadas: this recording is an example of this, and above all, of the great polyphonic tradition –la cardenche– that the peasants of the region produce and have preserved to date.

Verses of Pastorela

Strike the little birds

for the portal of Belém.

Strike to see the child

and just born.

The calandria sing joyfully

and also the little sparrow.

The calandria sing joyfully

to see the little boy.

And the turkey with his beauty,

and the falcon lightly.

Eagle is present

to see such lean beauty.

a shepherd girl was screaming

and working hard.

making a shirt

for Jesus my sweet owner.

Go and Gila without delay,

Come put on his shirt.

Will and love measure

and to lull him to sleep in his cradle.

Tracklist:

MUSICAL TRADITIONS FROM LA LAGUNA THE CARDENCHE SONG

SIDE 1

- A1 I’m going to die in the deserts –Traditional Cardenche Song– Sapioriz, municipality of Lerdo, Durango.

Performers: Eduardo Elizalde, second voice; Pablo García Antúnez, contralta or third voice; Juan Sanchez Ponce, pig or first voice.

- A2 On this street where I am passing –Traditional Cardenche Song– Sapioriz, municipality of Lerdo, Durango.

Performers: Eduardo Elizalde, second voice; Pablo García Antúnez, contralta or third voice; Juan Sanchez Ponce, pig or first voice.

- A3 I do not know why –Traditional Cardenche Song– Sapioriz, municipality of Lerdo, Durango.

Performers: Eduardo Elizalde, second voice; Pablo García Antúnez, contralta or third voice; Juan Sanchez Ponce, pig or first voice.

- A4 At the foot of a tree –Traditional Cardenche Song– Sapioriz, municipality of Lerdo, Durango.

Performers: Eduardo Elizalde, second voice; Pablo García Antúnez, contralta or third voice; Juan Sanchez Ponce, pig or first voice.

- A5 Little black eyes –Traditional Cardenche Song– Sapioriz, municipality of Lerdo, Durango.

Performers: Eduardo Elizalde, second voice; Pablo García Antúnez, contralta or third voice; Juan Sanchez Ponce, pig or first voice.

- A6 And look up, don’t be ashamed –Traditional Cardenche Song– Sapioriz, municipality of Lerdo, Durango.

Performers: Eduardo Elizalde, second voice; Pablo García Antúnez, contralta or third voice; Juan Sanchez Ponce, pig or first voice.

- A7 The moon rises and the sun sets –Traditional Cardenche Song– Torreon, Coahuila.

Performers: Ernesto Gonzalez Domene, sow or first voice; Alberto González Domene, third voice; Carlos Gonzalez Domene, arrequinte; Jaime de Lara Tamayo, second voice.

SIDE 2

- B1 From Torreon to Lerdo –March. Author: Pioquinto González– Torreon, Coahuila.

Performers: String quintet made up of the following musicians: Andrés Olvera, first violin; Albino García Hernández, second violin; Evaristo García Hernández, bandolón; Cenobio García Hernández, double bass; Reyes Gaucín Castillo, sixth guitar.

- B2 Tragedy of Pioquinto and Perfecto –Corrido tradicional Acardenchado– The Flower from Jumulco, Coahuila.

Performers: Cardencheros from the aforementioned locality, whose names were not provided.

- B3 The bakers –Traditional collective dances– Torreon, Coahuila.

Performers: String quintet made up of the following musicians: Andrés Olvera, first violin; Albino García Hernández, second violin; Evaristo García Hernández, bandolón; Cenobio García Hernández, double bass; Reyes Gaucín Castillo, sixth guitar.

- B4 The Filomena –March. Unknown author– Torreon, Coahuila.

Performers: Municipal Band of Torreón, Coahuila made up of the following musicians: Ernesto Villegas García, director; Salvador Enríquez Núñez, assistant director and solo trumpet; Noé Villaseñor Rodríguez, senior musician and clarinet soloist; Alfredo Salazar, piccolo; Angel Ríos Nava, clarinet; José Antonio Ibáñez Alba, clarinet; Francisco Vázquez Valdéz, clarinet; José Isabel Aguilera Rodela, clarinet; Lorenzo Martín del Campo, soprano saxophone; José Macías, tenor saxophone; Carlos Ríos, alto saxophone; J. Concepción Fabela, baritone; J. Ángel Salas, tuba; José Luz Cortina de la Fuente, big drum; Juan Flores, trombone; Emilio Núñez López, rod drum; Miguel Villaseñor Rodríguez, second saxor; Gabriel Villaseñor Rodríguez, cymbals; Gonzalo Villaseñor Rodríguez, trumpet; Jesus Villegas, trumpet; Gabriel Martínez Ibarra, trumpet; J. Concepción Rosales Ramírez, trumpet; Juan Manuel Huerta, timbales; Ernesto Villegas Flores, alto saxor.

- B5 Verses of pastorela. Sapioriz, municipality of Lerdo, Durango.

Performers: Eduardo Elizalde, second voice; Pablo García Antúnez, contralta or third voice; Juan Sánchez Ponce, pig or first voice. Genaro Chavarria.

Credits:

Irene Váquez Valle

Ernesto and Alberto Gonzézlez Domene

Secretary of Public Education

Mr. Fernando Solana Morales

Undersecretary of Culture and Recreation

Doctor Roger Díaz de Cosío

Director of the National Institute of Anthropology and History

Professor Gaston Garcia Cantu

Disc Series Director

teacher Irene Vázquez Valle

Irene Vázquez Valle: Engraver, Adjunct Material Writer, Editor

Roberto Portillo: Associate material writer

Victor Acevedo Martínez: Editor

Martín Audelo Chícharo: Editor

Guadalupe Loyola Zárate: Editor

H. Alejandro Castellanos Garrido: Editor, Researcher

Mónica Zamora Garduño: Editor; Social service

Gabriela González Sánchez: Editor; Social service

Guillermo Pous Navarro

Alfredo Huertero Casarrubias: Illustrator; Map illustration

Guillermo Santana Ramírez: Designer

Benjamín Muratalla: Director

Lino Balderas: Musician; Guitar

Ginio Montes: Musician; Guitar

Juan Sánchez Ponce: Singer; First voice

Eduardo Elizalde: Singer; Second voice

Genaro Chavarría: Singer; Second voice

Pablo García Antúnez: Singer; Contralta or third voice

Torreón Voice Ensemble: Singer

Notes:

Recording and notes by Irene Váquez Valle, except recording no. 2 of side B that was made by Ernesto and Alberto Gonzézlez Domene.

Links:

otroSold For:

Highest Price:

$700 MXMedium Price:

$700 MXCondition:

Media Condition:

Mint (M)Sleeve Condition:

Very Good (VG)Other Versions:

MUSICAL TRADITIONS FROM LA LAGUNA THE CARDENCHE SONG with the CENZONTLE / INAH label made in 1990.