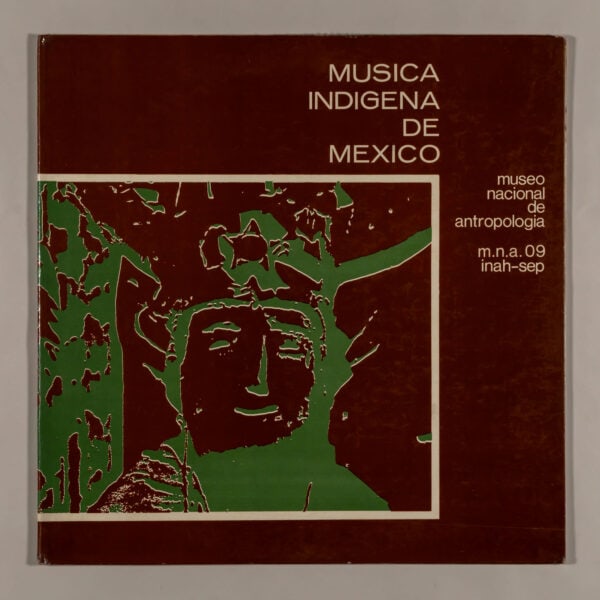

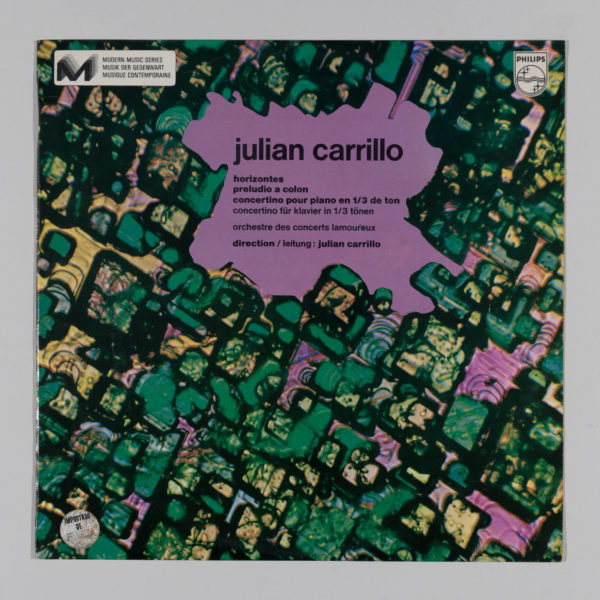

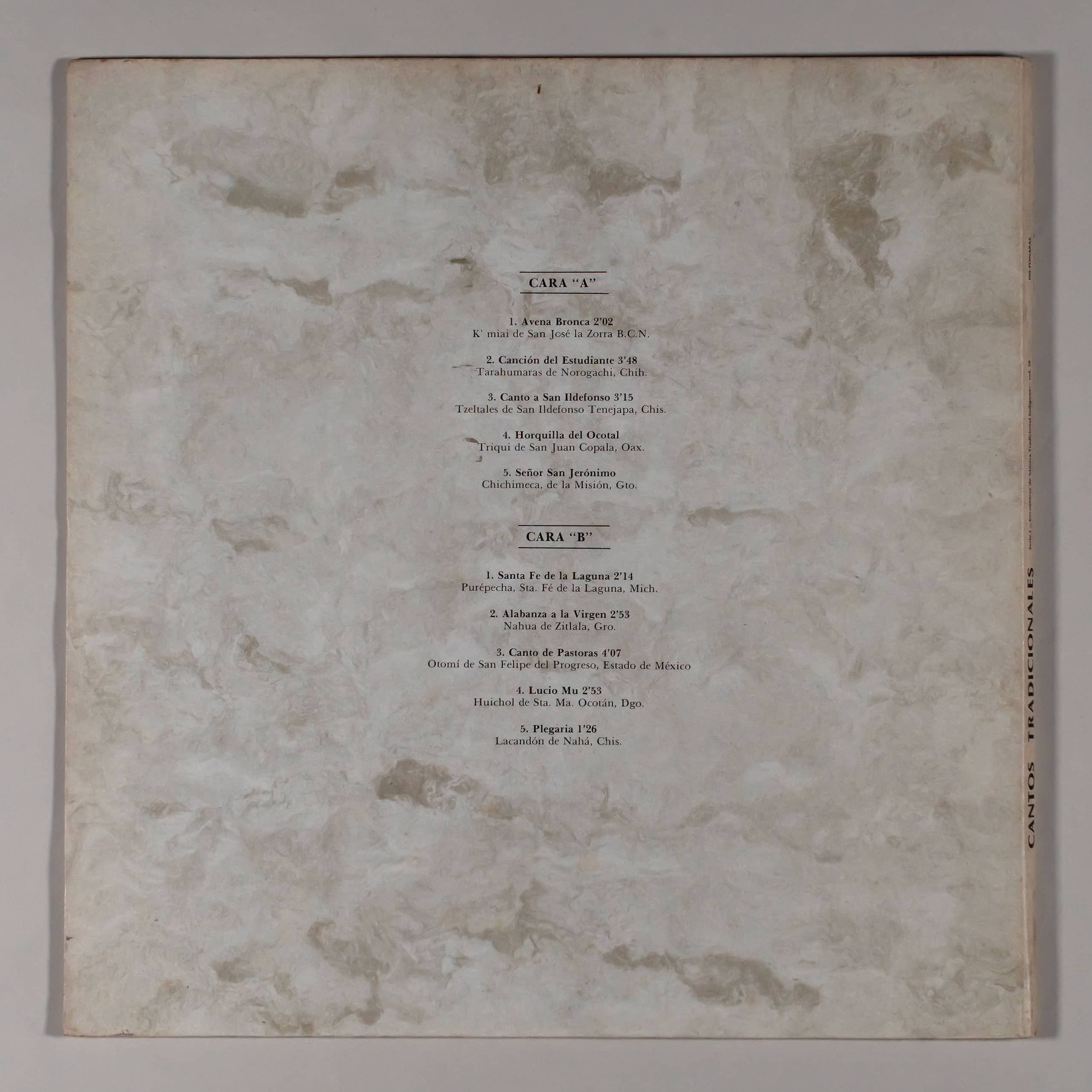

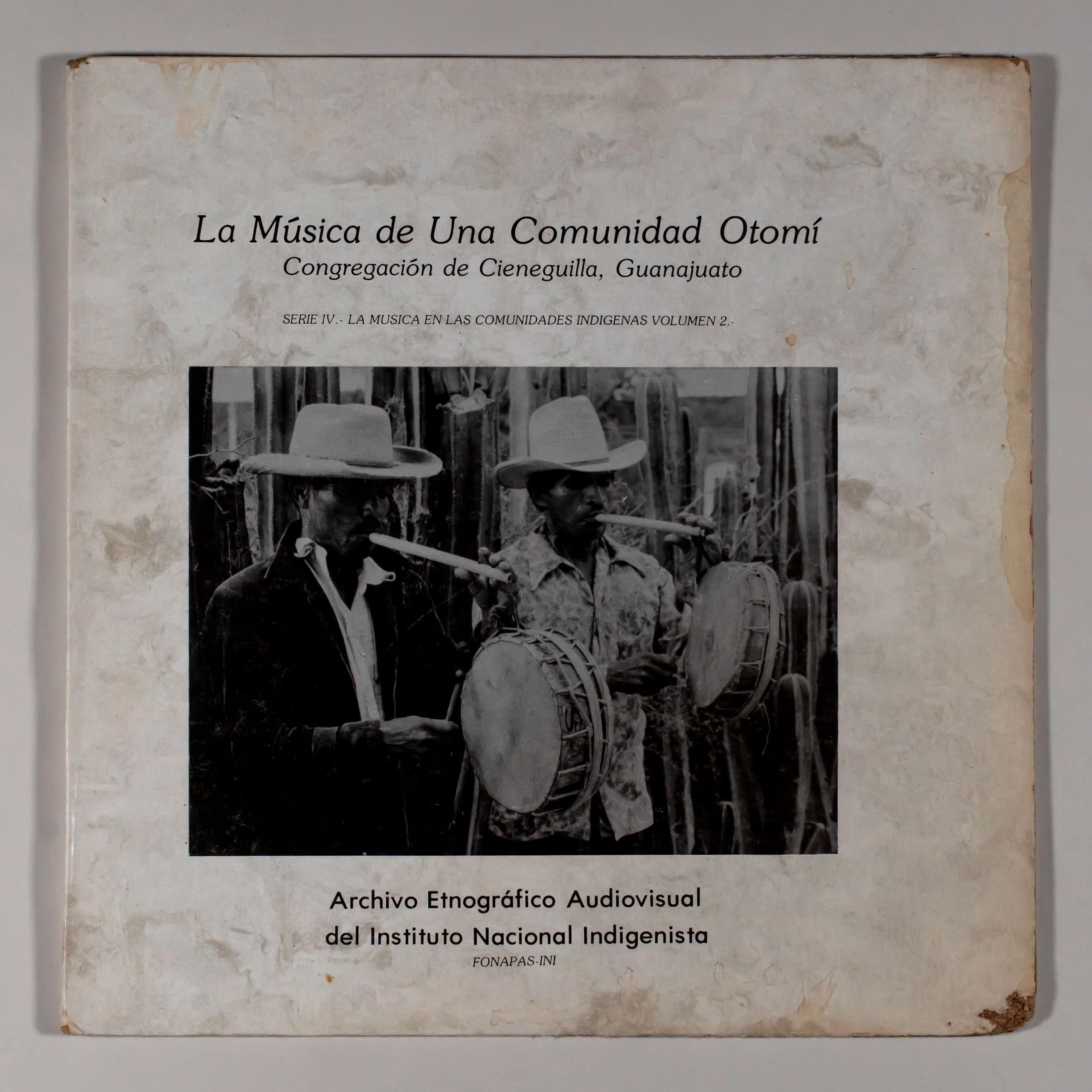

INTERETHNIC TRADITIONAL SONGS

Fonapas Ini

|

Label: FONAPAS-INI SERIES I, VOL. 10 Released: 1980 |

Country: Mexico Genre: Folk World & Country |

Info:

TRADITIONAL SONGS

Interethnic

Audiovisual Ethnographic Archive of the National Indigenous Institute

Series I –Meetings of Traditional Indigenous Music– vol. 10

INI-FONAPAS

Indigenous Songs

In all cultures, singing has been one of the first manifestations of ritual poetry, of the propitiatory rhythm that arose from the first priests to invoke the submission of the prey during the hunt, the growth of the plant or the appearance of favorable times. for agriculture. According to the conceptions of each people, the song has had a great variety of aesthetic, religious, funeral, curative and even war uses; however, it has never ceased to be one of the essential expressions of the human being.

Singing can be considered as a variation of speech, differing in that in singing the melodic intervals and rhythm are more marked; at the same time that one speaks, music is made, and in this case the mouth is the musical instrument. The sound is produced when the vocal cords vibrate due to the action of the air emitted by the lungs. These vibrations are amplified by the nasal and facial cavities or sinuses, which serve as a resonance chamber, giving the voice its quality.

According to the extent that people reach when singing, the voice has been academically classified as:

Coloratura, Soprano, Mezzosoprano, Contralto, Tenor, Baritone and Bass, from the highest to the lowest.

In Mexico, the oldest documents related to singing are found in ceramics, sculpture and painting, where there are countless motifs related to singing.

Let us remember, for example, the well-known hieroglyph that means to speak and that consists of a scroll coming out of the mouth of an individual. When this scroll has flower-like petals, it means that it is singing. In fact, some ancient Mexican cultures considered singing as a way to relate to the flowers of their own paradise, hence the term flower and song, which permeated the philosophy of Nahuatl-speaking peoples.

In a written way, the songs or religious songs of the ancient Mexicans contained in the manuscripts of Sahagún deposited in the National Library of Mexico are known. It is a collection of Nahua poems from Tlaxcala, Huejotzingo, Texcoco and Mexico, almost all of pre-Hispanic origin, although they were compiled between 1560 and 1570.

In ancient Mexico, the singers had a basically ritual function. Among the Aztecs they were called Cuicamatini (from cuicatl, song and matini, which he knows: “wise connoisseur of songs”). In an old description of the Nahua wise men (tlamatinime), it is expressly indicated that they were the ones who kept the books or codices of the song. This ancient tradition is still preserved among various indigenous peoples. Among the Huichol, for example, the singer belongs to the category of wise men (marakames) along with musicians, doctors and fortune tellers.¹

The friars used religious songs as one of the essential elements of catechism. But with them also came secular songs and old world instruments. Songs of love, war, lullaby and travel became popular quickly. It was customary to sing Christmas carols at the main festivals, many of them composed in Mexico such as those by Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, who has several compositions of this type in her work. The Christmas carol went from the religious to the secular, acquiring other names such as the serranilla.

As Bernal Díaz del Castillo and López de Gómara affirm, the Spanish ballads arrived in the new Spain with Hernán Cortés himself, the same as the corrido or the Andalusian bullfight, the younger sister of the ballad. From the Spanish Romance the corrido was derived: one of the most typical forms of Mexican popular song. The indigenous songs were preserved in the remote regions of the mountains in groups that managed to maintain their individuality; The rest, which can be considered as the mestizo population, adopted what was brought by the Spaniards, such as morning songs and Christmas carols, which acquired local forms. The Augustinian monks implanted the Christmas bonus masses with songs. The novena of the Child Jesus was also celebrated with songs of greetings, farewells, lullabies, and throughout the country the musical geography was dressed in “mixed genres.” This phenomenon was also influenced by the songs of troubadours and minstrels, of romanceros from all the Spanish provinces, as well as the indigenous ingredient was decisive in terms of the structure of the song, and according to Miguel M. Ponce:²

“By the second half of the 18th century, the Mexican popular song is divided into two parts: in the first, the frankly melodic phrase is exposed, ending in the same tonality in which it began.

The second is made up of two bars that are repeated to complete the musical phrase, and then the refrain, characteristic of the end of the first part. The chords that were used to harmonize are the natural ones on the tonic, the fifth and the fourth of the tonality”

At this time the national repertoire was filled with a large number of children’s songs, the best known being the lullabies that are generally the product of mothers, nannies and nurses who in turn transmit and preserve them.

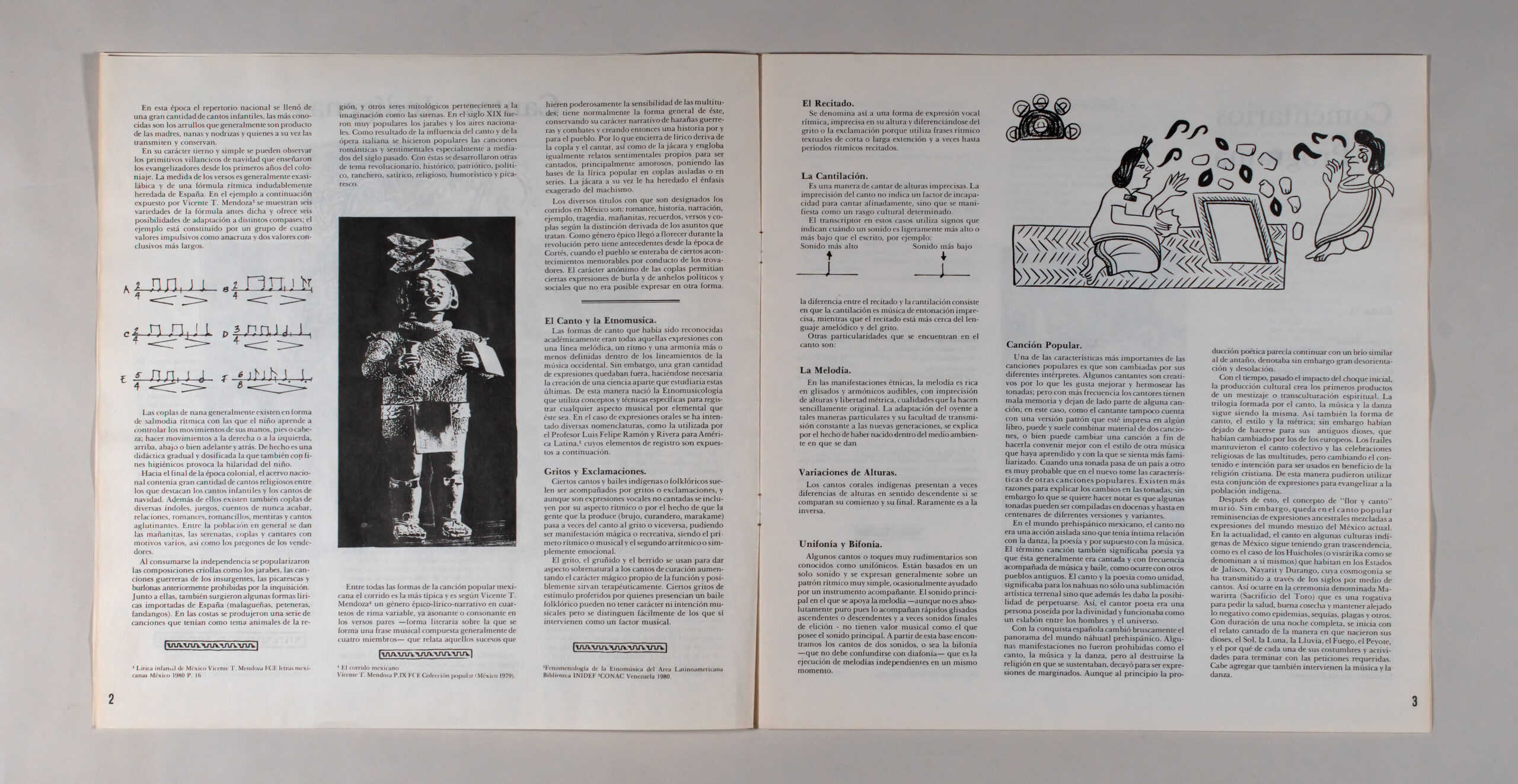

In its tender and simple character you can see the primitive Christmas carols that the evangelizers taught from the first years of colonial times. The measure of the verses is generally exasyllabic and of a rhythmic formula undoubtedly inherited from Spain. In the example below exposed by Vicente T. Mendoza³ six varieties of the aforementioned formula are shown and offer six possibilities of adaptation to different compasses; the example is made up of a group of four impulsive values as upbeat and two longer conclusive values.

Lullaby couplets generally exist in the form of rhythmic chants with which the child learns to control the movements of his hands, feet, or head; make movements to the right or to the left, up, down or forward and backward. In fact, it is a gradual and dosed didactic that also for hygienic purposes causes the hilarity of the child.

Towards the end of the colonial era, the national heritage contained a large number of religious songs, among which children’s songs and Christmas songs stand out. In addition to them there are also verses of various kinds, games, never-ending stories, relationships, romances, ballads, lies and binding songs. Among the population in general there are mornings, serenades, songs and songs with various motives, as well as the vendors’ proclamations.

When independence was consummated, Creole compositions such as syrups, the war songs of the insurgents, the picaresque and mocking songs previously prohibited by the inquisition, became popular. Along with them, some lyrical forms imported from Spain also arose (malagueñas, peteneras, fandangos). On the coasts, a series of songs were produced that had animals from the region as their theme, and other mythological beings belonging to the imagination such as mermaids. In the 19th century, syrups and national airs were very popular. As a result of the influence of Italian singing and opera, romantic and sentimental songs became popular, especially in the middle of the last century. With these, others of revolutionary, historical, patriotic, political, ranchero, satirical, religious, humorous and picaresque themes were developed.

Among all the forms of the Mexican popular song, the corrido is the most typical and is according to Vicente T. Mendoza⁴

an epic-lyrical-narrative genre in quatrains with variable rhyme, either assonant or consonant in the even verses –literary form on which a musical phrase generally composed of four members is formed– that recounts those events that powerfully hurt the sensibilities of the multitudes ; It normally has the general form of the latter, preserving its narrative character of war exploits and combats and thus creating a story by and for the people. As far as lyric is concerned, it derives from the couplet and singing, as well as from the jácara and also includes sentimental stories to be sung, mainly love stories, laying the foundations of popular lyrics in isolated couplets or in series. The jácara in turn has inherited the exaggerated emphasis of machismo.

The various titles by which corridos are designated in Mexico are: romance, history, narration, example, tragedy, morning, memories, verses and couplets according to the distinction derived from the issues they deal with. As an epic genre it flourished during the revolution but it has antecedents since the time of Cortés, when the people learned of certain memorable events through the troubadours. The anonymous nature of the couplets allowed certain expressions of mockery and political and social desires that could not be expressed in any other way.

Singing and Ethnomusic.

The forms of singing that had been recognized academically were all those expressions with a more or less defined melodic line, rhythm and harmony within the guidelines of Western music. However, a large number of expressions were left out, making it necessary to create a separate science that would study the latter. In this way, Ethnomusicology was born, which uses specific concepts and techniques to record any musical aspect, however elementary it may be. In the case of oral expressions, various nomenclatures have been tried, such as the one used by Professor Luis Felipe Ramón y Rivera for Latin America,⁵ whose registration elements are exposed below.

Shouts and Exclamations.

Certain indigenous or folkloric songs and dances are usually accompanied by shouts or exclamations, and although they are non-sung vocal expressions, they are included because of their rhythmic aspect or because the people who produce them (witch, healer, marakame) sometimes go from I sing to the cry or vice versa, being able to be a magical or recreational manifestation, being the first rhythmic or musical and the second arrhythmic or simply emotional.

The scream, growl and howl are used to give healing chants a supernatural aspect, increasing the magical character of the function and possibly serving therapeutically. Certain shouts of encouragement uttered by those who witness a folkloric dance may not have a musical character or intention, but they are easily distinguished from those that do intervene as a musical factor.

The Recited.

This is the name given to a form of rhythmic vocal expression, imprecise in its height and differing from the cry or exclamation because it uses short or long rhythmic-textual phrases and sometimes even recited rhythmic periods. The Cantillation. It is a way of singing of imprecise heights. The imprecision of the song does not indicate a factor of incapacity to sing in tune, but it manifests itself as a certain cultural trait. The transcriber in these cases uses signs that indicate when a sound is slightly higher or lower than the written one, for example: Higher sound Lower sound The difference between reciting and cantillation is that the cantillation is music with imprecise intonation , while the recitation is closer to the melodic language and the cry. Other particularities found in the song are:

The Cantillation.

It is a way of singing of imprecise heights. The imprecision of the song does not indicate a factor of incapacity to sing in tune, but it manifests itself as a certain cultural trait. The transcriber in these cases uses signs that indicate when a sound is slightly higher or lower than the written one, the difference between the recited and the cantillation is that the cantillation is imprecise intonation music, while the recited is closer to the melodic language and scream.

Other particularities found in the song are:

The melody.

In ethnic manifestations, the melody is rich in audible glissandos and harmonics, with imprecise pitches and metric freedom, qualities that make it simply original. The listener’s adaptation to such particular ways and his faculty of constant transmission to the new generations, is explained by the fact of having been born within the environment in which they occur.

Height Variations.

Indigenous choral songs sometimes have pitch differences in a descending direction if their beginning and end are compared. It is rarely the other way around.

Unifonia and Biphony.

Some very rudimentary songs or touches are known as unifonic. They are based on a single sound and are generally expressed on a very simple rhythmic pattern, occasionally aided by an accompanying instrument. The main sound on which the melody rests –although it is not absolutely pure as it is accompanied by fast ascending or descending glissandos and sometimes final elision sounds– does not have a musical value like the one possessed by the main sound. From this base we find the songs of two sounds, that is, the biphony –not to be confused with crosstalk– which is the execution of independent melodies at the same time.

Popular song.

One of the most important characteristics of popular songs is that they are changed by their different interpreters. Some singers are creative so they like to enhance and beautify the tunes; but more often the singers have a bad memory and leave out part of a song; in this case, as the singer also does not have a standard version that is printed in a book, they can and often do combine material from two songs, or they can change a song to make it better fit the style of other music they have learned and with which you feel most familiar. When a tune passes from one country to another, it is very likely that in the new one it will take on the characteristics of other popular songs. There are more reasons to explain the changes in tunes; however, what is to be noted is that some tunes can be compiled into dozens and even hundreds of different versions and variants.

In the Mexican pre-Hispanic world, singing was not an isolated action but was closely related to dance, poetry and, of course, music. The term song also meant poetry since poetry was generally sung and often accompanied by music and dance, as is the case with other ancient peoples. Song and poetry as a unit, meant for the Nahuas not only an earthly artistic sublimation but also gave them the possibility of perpetuating themselves. Thus, the poet-singer was a person possessed by divinity and functioned as a link between men and the universe.

With the Spanish conquest, the panorama of the pre-Hispanic Nahuatl world changed abruptly. Some manifestations were not prohibited, such as singing, music and dance, but when the religion on which they were based was destroyed, they declined to be expressions of the marginalized. Although at first the poetic production seemed to continue with a verve similar to that of yesteryear, it nevertheless denoted great disorientation and desolation.

Over time, after the impact of the initial shock has passed, cultural production creates the first products of spiritual crossbreeding or transculturation. The trilogy formed by the song, the music and the dance continues being the same. So also the way of singing, the style and the metric; however, they had ceased to be made for their old gods, which had changed to those of the Europeans. The friars maintained the collective singing and religious celebrations among the crowds, but changing the content and intention to be used for the benefit of the Christian religion. In this way they were able to use this conjunction of expressions to evangelize the indigenous population.

After this, the concept of “flower and song” died. However, reminiscences of ancestral expressions mixed with expressions of the mestizo world of present-day Mexico remain in the popular song. At present, the song in some indigenous cultures of Mexico continues to have great importance, as is the case of the Huicholes (or visrárika as they call themselves) who live in the States of Jalisco, Nayarit and Durango, whose cosmogony has been transmitted through the centuries through songs. This is the case in the ceremony called Mawarirra (Bull Sacrifice) which is a prayer to ask for health, a good harvest and to keep away the negative such as epidemics, droughts, plagues and others. Lasting a full night, it begins with the sung story of the way in which their gods were born, the Sun, the Moon, the Rain, the Fire, the Peyote, and the reason for each of their customs and activities for finish with the required requests. It should be added that music and dance are also involved.

¹ Enciclopedia de México (1978) Tomo II.

² Escritos y Composiciones Musicales (1917)

³ Lirica infantil de México Vicente T. Mendoza FCE letras mexicanas México 1980 P. 16

⁴ El corrido mexicano Vicente T. Mendoza P.IX FCE Colección popular (México 1979).

⁵ Fenomenología de la Etnomúsica del Área Latinoamericana Biblioteca INIDEF CONAC Venezuela 1980.

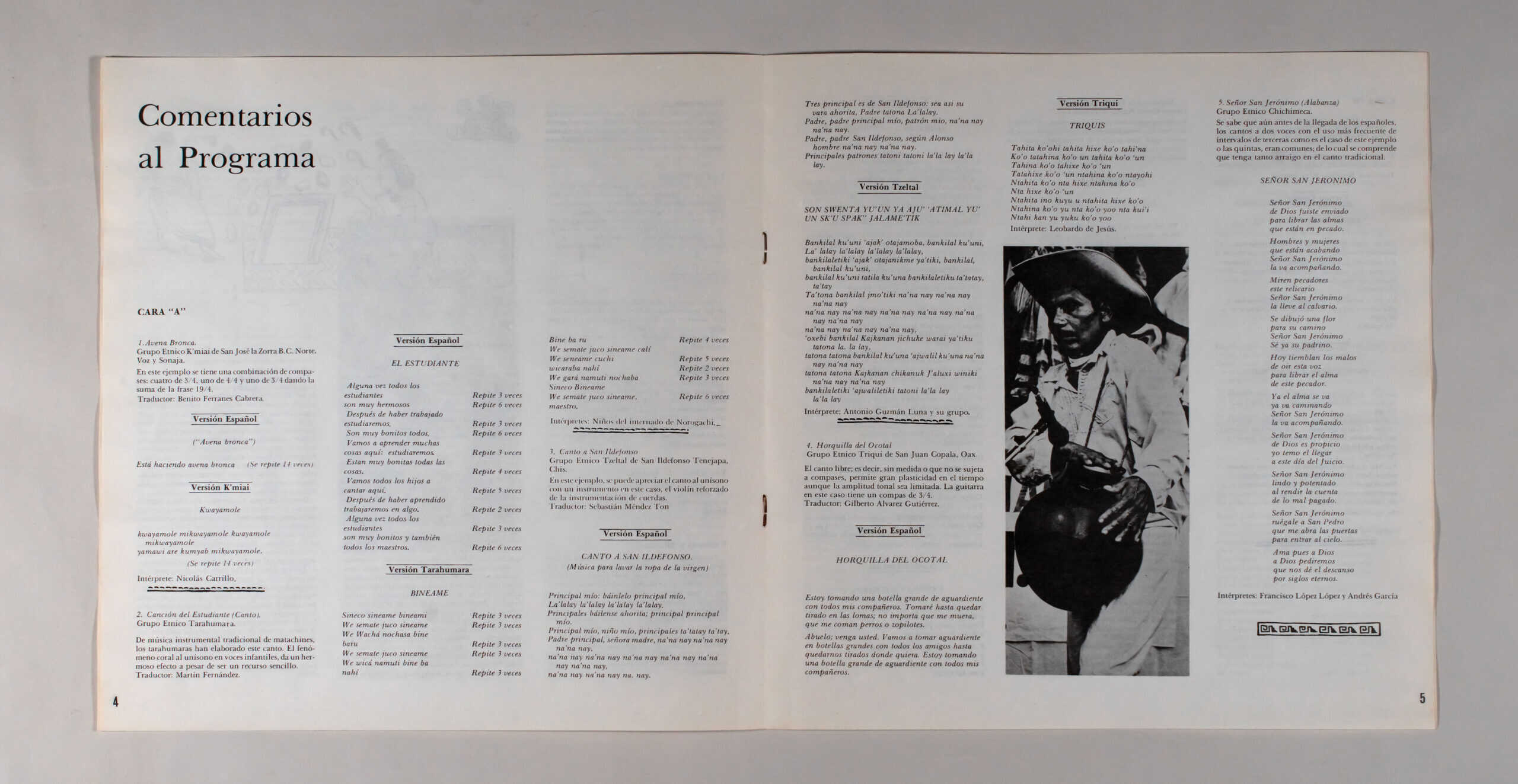

Comments to the Program

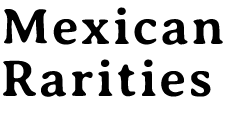

SIDE “A”

1. Rough Oats.

K’miai Ethnic Group from San José la Zorra B.C. North. Voice and Rattle.

In this example we have a combination of measures: four in 3/4, one in 4/4 and one in 3/4 giving the sum of the phrase 19/4.

Translator: Benito Ferranes Cabrera.

English version

(“Rough Oats”)

He is making rough porridge (Repeats 14 times)

K’miai version

Kwayamole

kwayamole mikwayamole kwayamole

mikwayamole

yamawi are kumyab mikwayamole.

(Repeats 14 times)

Performer: Nicolas Carrillo.

2. Student Song (Song).

Grupo Etnico Tarahumara.

From traditional matlachine instrumental music, the Tarahumara have elaborated this song. The unison choral phenomenon in children’s voices gives a beautiful effect despite being a simple resource.

Translator: Martin Fernandez.

English version

THE STUDENT

Ever all

students

repeat 3 times

they are so beautiful

repeat 6 times

after having worked

will study.

repeat 3 times

They are all very pretty

repeat 6 times

We are going to learn a lot

things here: we will study.

repeat 3 times

They are all very beautiful

things.

repeat 4 times

Let all the children

sing here.

repeat 5 times

after having learned

We’ll work on something.

repeat 2 times

ever all

students

repeat 3 times

they are very beautiful and also

all teachers.

repeat 6 times

Tarahumara Version

JOIN ME

Sineco sineame bineami

Repeat 3 times

We semate juco sineame

Repeat 3 times

We Wachá nochasa bine

baru

Repeat 3 times

We semate juco sineame

Repeat 3 times

We wicá namuti bine ba

nahi

Repeat 3 times

Bine ba ru

Repeat 4 times

We semate juco sineame calí

We seneame cuchi

Repeat 5 times

wicaraba nahi

Repeat 2 times

We gará namuti nochaba

Repeat 3 times

Sineco Bineame

We semate juco sineame,

Repeat 6 times

master.

Performers: Children from the Norogachi boarding school.

3. Singing to San Ildefonso

Tzeltal Ethnic Group of San Ildefonso Tenejapa, Chis.

In this example, you can see the singing in unison with an instrument in this case, the violin reinforced by the string instrumentation.

Translator: Sebastián Méndez Ton.

English version

SINGING TO SAN ILDEFONSO.

(Music to wash the clothes of the virgin)

Main mine: bathe it main mine,

La’lalay la’lalay la’lalay la’lalay.

Principales dance right now; main main mine.

Principal mine, my child, principales ta’tatay ta tay.

Principal father, lady mother, nå’na nay na’na nay na’na nay,

na’na nay na’na nay na’na nay na’na nay na’na nay na’na nay,

na’na nay na’na nay na, nay.

Three principal is from San Ildefonso: so be your altar right now, Tatona Father La’lalay.

Father, my principal father, my patron, na’na nay na’na nay.

Father, father San Ildefonso, according to Alonso man na’na nay na’na nay.

Main patterns tatoni tatoni la’la lay la’la lay.

Tzeltal Version

SON SWENTA YU’UN YA AJU’ ‘ATIMAL YU’ UN SK’U SPAK” JALAME’TIK

Bankilal ku’uni ‘ajak’ otajamoba, bankilal ku’uni,

La’ lalay la’lalay la’lalay la’lalay,

bankilaletiki ‘ajak’ otajanikme ya’tiki, bankilal, bankilal ku’uni,

bankilal ku’uni tatila ku’una bankilaletiku ta’tatay, ta’tay

Ta’tona bankilal jmo’tiki na’na nay na’na nay na’na nay

na’na nay na’na nay na’na nay na’na nay na’na nay na’na nay

na’na nay na’na nay na’na nay,

‘oxebi bankilal Kajkanan jichuke warai ya’tiku tatona la. la lay,

tatona tatona bankilal ku’una ‘ajwalil ku’una na’na nay na’na nay

tatona tatona Kajkanan chikanuk l’aluxi winiki na’na nay na’na nay

bankilaletiki ‘ajwaliletiki tatoni la’la lay la’la lay

Performer: Antonio Guzmán Luna and his group.

4. Ocotal Fork

Triqui Ethnic Group from San Juan Copala, Oax.

The free song; that is to say, without measure or that is not subject to compasses, it allows great plasticity in time even though the tonal amplitude is limited. The guitar in this case has a 3/4 time signature.

Translator: Gilberto Alvarez Gutiérrez.

English version

OCOTAL FORK

I’m drinking a big bottle of brandy

with all my colleagues. I’ll drink until I stay

lying on the hills; It doesn’t matter if I die

Let dogs or vultures eat me.

Grandfather; come you. Let’s drink brandy

in big bottles with all the friends up

stay stranded wherever. I’m drinking

a large bottle of brandy with all my

companions.

Triqui Version

TRIQUIS

Tahita ko’ohi tahita hixe ko’o tahi’na

Ko’o tatahina ko’o un tahita ko’o ‘un

Tahina ko’o tahixe ko’o ‘un

Tatahixe ko’o ‘un ntahina ko’o ntayohi

Ntahita ko’o nta hixe ntahina ko’o

Nta hixe ko’o ‘un

Ntahita ino kuyu u ntahita hixe ko’o

Ntahina ko’o yu nta ko’o yoo nta kui’i

Ntahi kan yu yuku ko’o yoo

Performer: Leobardo de Jesus.

5. Lord Saint Jerome (Praise)

Chichimeca Ethnic Group.

It is known that even before the arrival of the Spaniards, songs for two voices with the more frequent use of intervals of thirds, as in the case of this example or fifths, were common; from which it is understandable that it has so much roots in traditional singing.

LORD SAINT JEROME

Lord Saint Jerome

you were sent from God

to free the souls

that they are in sin.

Men and women

that they are ending

Lord Saint Jerome

he is accompanying her.

look sinners

this locket

Lord Saint Jerome

take her to Calvary.

a flower was drawn

for your way

Lord Saint Jerome

I already know her godfather.

Today the bad guys tremble

to hear this voice

to free the soul

of this sinner

the soul is leaving

he’s already walking

Lord Saint Jerome

he is accompanying her.

Lord Saint Jerome

of God is propitious

I fear arriving

to this Judgment Day.

Lord Saint Jerome

cute and potent

when rendering account

of how badly paid

Lord Saint Jerome

pray to Saint Peter

open the doors for me

to enter heaven.

So he loves God

we will ask God

may he give us rest

for everlasting centuries.

Performers: Francisco López López and Andrés García

SIDE “B”

1. Santa Fe de la Laguna

Purépecha Ethnic Group from Santa Fe de la Laguna, Michoacán.

The song or pirecua as the Purépechas call it is generally made in two voices in thirds.

Translator: Benedina Silva Jimenez

English version

“SANTA FE DE LA LAGUNA”

Those from Santa Fé de la Laguna are going to sing a

abajeño that says pretty.

That lady that comes there, she hurt me

heart. That lady who comes there, a lot

she a lot she made me cry.

(Is repeated.)

I was going to speak to him between those two corners, and

she comes to me with the pitcher in her hand and leaves

by the way.

(Is repeated.)

Purepecha Version

“SANTA FE DE LA LAGUNA”

Santa fé de la laguna anápuecha,/ Nireshinishi

ma pireni,/ abajenio enga sháni sése arhihka./

(Is repeated)

Indé marikua inde enga jini jurhéhka,/ inderini

jindini mintsita atachisti,/ indé marikua indenga

jiní jurhahka inderini jindeni kanikua kanikua

uekua phikustia./

(Is repeated)

Noshka ji khoru nirasham uandahpani tzimani

eskinechani jimbó,/ ka indé jini jurhashini

kamukua tirhihtatini ka jinderini iskurini

uanotama sani.

(Is repeated)

(Everything is repeated.)

Performers: Dimas Brothers

2. Praise to the Virgin

Nahua Ethnic Group of Zitlala, Gro.

In this example we observe few tones and the phenomenon known as canonical heterophony in which people sing as best they can and in a natural way

Translator: Toribio Pascual Muñoz, form harmonicas.

English version

PRAISE TO THE VIRGIN

- You lady you if you hear from your aunt.

Mother, you will even fix your heart

and your pickets The blood is coming down.

If you hear from your aunt I’m yelling at you

and crossing our words and hands and fingers.

Wait, they already cooked in the sun: we are sad

and he is also seeing us that here we cry.

You tell them to walk on their knees.

Come with us. Bring us our blessing.

- We are really many, we are going to shout here on earth.

Here he has to tell us come with us you too.

I’m going out as the theme says to your waist

With all due respect, pretty little girl.

Holy Mary pray for us

hour hour we are also going to say

her words to our Lord Jesus Christ

for her to come down here with us.

- God her little mother, she formed us so that we could live.

God your little mother, where are you going?

You go to the land of Jerusalem

What are you going to do?

I’m going to look for your honest little son.

What grace is our father like this, my honest son?

God honored Jesus Nazareno where do you live alone?

I found it already. He was coming to the land of Jerusalem.

They are already playing the instruments that we will bring.

- We already brought them here, they are already standing here.

The stars are also shining.

Also the flowers are blooming.

Honored little mother of God. She formed us so that we could live.

It is not true that the honest one is your son.

Honored is the God.

And we will take him to the land of Jerusalem

and we’ll leave it there.

Nahualt Version

PRAISE TO THE VIRGIN

- Mosiualtilis mo si mokakil de tia

totetlayokolis nansini y toyolisisi

intla tesopinilisi in tena temo telisi

ma si mokakil de tia timisonsasilia

in totlatotoksin in tipilua nika

moisikan in tonalsisiui siknolistikan

iuan chokistika y nikan chokis

ma ikile tosipan tlatokasinin

matoueikpan tesamouikili motetlayokolis

- Y tonalansisin la iuan sankis y nikan tlaltipan

totototokan tetlamouikili iuan in senkiska in

teneualonikisas y tlakilia mosilansin

moknauakasintli senkiska ichpokasintli

Santa Maria matopan si motlatolti

nansinansinin iketi kinochiluiski y

tlateneualsi in totiki Dios y Jesucristo

maimochiua.

- Dios y maui nansını tlasosiuasili

Dios y maui nansini kanika timouika

ompa nimouikan Jerosalen Tlalpan

tlinon timochiuilis nimotetemouilis momauis

mosentekonesin

tlinimauis totasin momauis sentekonesin

y mauis totasin Jesus Nazareno kasauel yeuasin

monikmonamikili yo nasiltitika Jerosalen Tlalpan

yo kimouikiliki tlasosonalistika iuan

Tlapisilistika.

- Yo kimoyekanilika. ompa yenutika

sitlal kueponalistika sochi tlaseselistika

Dios y maui nansini tlasosiuasili

amo simamansinon momauis sentekonesin

yo kimouikiliki Jerosalen Tiuapan

yo kimosalouilito yo kimo

Performers: Women of Zitlala, Guerrero.

3. Song of Shepherds.

Otomí Ethnic Group of San Felipe del Progreso, Edo. from Mex.

In this example, heterophony is also presented. It is also worth noting the great participation of women in terms of singing in the indigenous world.

Translator: Juvencio Enríquez Calixto.

English version

SONG OF SHEPHERDS.

Come on come on father Jesus Christ

We are going to see Bethlehem.

Come on come on father Jesus Christ

We are going to see Bethlehem.

And then my father will be here

and in the skies.

And then my father will be here

and in the skies.

My mother Mary has sent us

to come here.

My mother Mary has sent us

to come here.

My father Salvador has sent us

to come see

my father Salvador has sent us

to come see

Mother Elena has sent us

to come here.

Mother Elena has sent us

to come here.

And mother Guadalupe has sent us

to see you here

and mother Guadalupe has sent us

to see you here

And the Virgin of Carmen has sent us

to see you here

and the Virgin of Carmen has sent us

to see you here

And our father Joseph has sent us

to see you here

And our father Joseph has sent us

to see you here

Oh! Virgin Mary, we retire to

Our home.

Oh! Virgin Mary, we retire to

Our home.

Give us the blessing that we are leaving

to our home.

Give us the blessing that we are leaving

to our home.

Let’s walk, let’s walk and we’ll go

because the afternoon is coming.

Let’s walk, let’s walk and we’ll go

because the afternoon is coming.

Since father Salvador

It’s waiting for us, yeah

Because already the father Salvador

he is already waiting for us, now

Let’s walk, let’s walk, we’re leaving

because our home is far away.

Let’s walk, let’s walk, we’re leaving

because our home is far away.

because the virgin Elena

she’s going to separate us.

because the virgin Elena

she’s going to separate us.

We already ask you to thank you.

We are going to our home.

We already ask you to thank you.

We are going to our home

As long as I have life

I have to see you again.

As long as I have life

I have to see you again.

Otomi Version

SONG OF SHEPHERDS.

Maha maha tata cita

ja nu Belen nuju de

Maha maha tata cita

ja nu Belen nuju de

Ya xum-u numa zi ndatha

Nuua zi mataa mahet-si

Ya xum-u numa zi ndatha

nuua zi mataa mahet-si

Nu ma mee ga Emali xpa

pencaguá ga ecahe

Nu ma mee ga Emali xpa

pencaguá ga ccahe

Nu ma tada Salvadó xa

Pencaguá ga nua-hé

Nu ma tada Salvadó xa

pencaguá ga nua-hé

Nu ma mee ga Elena xpa

pencaguá ga Ecahé

Nu ma mee ga Elena xpa

pencaguá ga Ecahé

Nu ma mee ga Elupe xa

pencaguá ga nua-hé

Nu ma mee ga Elupe xa

pencaguá ga nua-hé

Nu ma mee ga Ecarme xa

pencaguá ga nu-ahe

Numa mee ga Ecarme xa

pencaguá ecahé

Numa tada Ejuse xa

Pencagua ga nua-he

Numa tada Ejuse xa

pencagua ga nua-he

Numa mee ga Emalilla ga

magahe ma nguhé

Numa mee ga Emalilla ga

magahé ma nguhé

Daje ni xi japi ya ga

magahe ma nguhé

Daje ni xi japi ya ga

magahé ma nguhé

Noju ñoju ga maha

porque ya vi zuju nu ndeé

Noju ñoju ga maha porque

ya vi zuju nu ndeé

Ya que ya ma tada Salvador

Ya mi tobgahú

porque ya ma tada Salvador porque

ya mi gue bi tobgahú

Noju ñoju ga maha

porque randa ya manguhú

Noju ñoju ga maha

porque randa ya manguhú

Ya ma mee ga Elena

porque ya ga güecahú

porque ya ma mee ga Elena

porque ya ga güecahú

Ya di apa njamamadi ya ga

magahé manguhé

Ya dí apa njamamadí ya ga

magahé ma nguhé

Nugui que da nja ma nzaqui

pa ga pengaja ga nu-i

Nugui que da nja ma nzaqui

pe ga pengaga ga hu-i

Performers: The Dance of San Felipe del Progreso, State of Mexico.

4. Lucio Mu

Huichol Ethnic Group of Sta. Ma. Ocotán, Dgo.

The use of modern and ancestral elements in the texts of the songs reflect in some way a process that can in some cases like this be very rich.

Translator: Eliseo Castro Villa

English version

LUCIO MU

Lucio Lucio mu

Lucio Lucio mu

Lucio Lucio mu

In the center of Tepic

In the center of Tepic

In the center of Tepic

In the bank you have

In the bank you have

In the bank you have

In the center of Tepic

In the center of Tepic

In the bank you have

Lucio Lucio Mu

Small money

In the bank you have

In the center of Tepic

In the center of Tepic

In the bank you have

Lucio Lucio Mu

Lucio Lucio Mu

Small money

Small money

In the center of Tepic

What do you care

Lucio Lucio Mu

Lucio Lucio Mu

In the center of Tepic

In the center of Tepic

In the center of Tepic

Small money

What do you care

In the bank Lucio mu

Small money

Small money

Small money

Lucio mu in the center

From Tepic

In the center of Tepic

Lucio Lucio Mu

Lucio Lucio Mu

Lucio Lucio Mu

We have money

In the center of Tepic

We have money

Small money

Small money

What do you care

In the center of Tepic

Lucio Lucio Mu

Small money

What do you care

Lucio Lucio Mu

Small money

Small money

Small money

What do you care

In the center of Tepic

In the bank you have

Lucio Lucio Mu

Lucio Lucio Mu

Lucio Lucio Mu

Cio Lucio

Lucio Lucio Lucio mu

Money Lucio Lucio mu

Lucio Lucio Mu

In the center of Tepic

In the center of Tepic

Lucio Lucio Mu

Small money

Small money

Lucio Lucio Mu

Lucio Lucio Mu

Lucio Lucio Mu

Huichol Version

LUCIO MU

Lucio Mu

Lucio Lucio Mu

Lucio Lucio Mu

Lucio Lucio Mu

Tepequi jisrrapamu

Tepequi jisrrapamu

Tepequi jisrrapamu

banco pemesreyamu

banco pemesreyamu

banco pemesreyamu

Tepequi jisrrapamu

Tepequi jisrrapamu

banco pemesrrayamu

Lucio Lucio mu

tumini tulisrri

banco pemesreyamu

Tepequi jisrrapamu

Tepequi jisrrapamu

banco pemesreyamu

Lucio Lucio mu

Lucio Lucio mu

tumini turisrrimu

tumini turisrrimu

Tepequi jisrrapamu

alipemezreyamu

Lucio Lucio Mu

Lucio Lucio mu

tepequi jisrrapamu

tepequi jisrrapamu

tepequi jisrrapamu

tumini tulisrri Mu

alipemezreyamu

banco Lucio Mu

tumini tulisrrimu

tumini tulisrrimu

tumini tulisrrimu

Lucio Mu Tepequi jisrrapamu

tepequi jisrrapamu

Lucio Lucio Mu

Lucio Lucio Mu

Lucio Lucio Mu

temestreya tumini

tepequis jisrrapamu

temestreya tumini

tumini turisrrimu

tumini turisrrimu

alipemezro yamu

tepequi jisrrapamu

Lucio Lucio Mu

tumini tulisrrimu

alipemezregamu

Lucio Lucio M

tumini turisrrimu

tumini turisrrimu

tumini turisrrimu

alipemezreyamu

Tepequi jisrrapamu

banco pemesreyamu

Lucio Lucio Mu

Lucio Lucio Mu

Lucio Lucio Mu

Lucio Lucio

Lucio Lucio Lucio Mu

Tulisrri Lucio Lucio Mu

Lucio Lucio Mu

Tepequi jisrrapamu

Tepequi jisrrapamu

Lucio Lucio Mu

tumini tulisrrimu

tumini tulisrrimu

Lucio Mu

Lucio Lucio Mu

Lucio Lucio Mu

Lucio Lucio Mu

Performers: Group of Banks of Calitique Nayarit.

5. Prayer

Lacandon Ethnic Group of Nahá, Chis.

The a cappella voice, that is, without instrumental accompaniment, is undoubtedly the easiest way to participate in music. This song, little influenced by the West, conveys the personality of an ethnic group, and a simple but beautiful way of singing.

Translator: K’ayum Mash

Spanish version

PRAYER

Call him, eh call that Chob (Akinchob)

so she gave it to “I’tsah Noh K’uh” to taste.

Here, that’s why it’s the offering,

(so that) you call the heart of Heaven a little bit, you will call it.

It’s the same. Still the same.

Can’t even (can) get up

“Sakapuk” is punishing her

Put your hand to heal her.

Put it on, go

Here is (the offering of) love for you.

Here is that. heal her a little

like this personally, so that her food may be composed,

so that she thus composed she may drink.

That one hasn’t touched anything (which she shouldn’t), “I’tsah Noh K’uh”

that, “Chob” (Akinchob), a little bit (please)

you shall call: Go up and call him, Chak Chob (title of Akinchob).

That! You go to (where) Chak Chob is

(It is) really an offering (to) your mouth.

Put your hand (and) heal it.

Put your hand to heal her, Chob.

Eh, you have to cure her for that,

Illness (chronic) rises

Put your hand to heal her,

put your hand oh “Chob”.

Therefore you will take your offering of “White Water” (ceremonial Atole)

(Please) just heal her, or Chob.

Forgive, there (in your) censer.

Forgive me, there in your censer.

Excuse me, so that you take

the offering… small gourds of baalché. (ceremonial)

That will be in the “Yak’in”

That (will be) at the “Navinen” ceremony.

Lacandon Version

PRAYER

Ka t’aneh, e t’aneh. La chob

tuneh uts’ah I’tsah Noh Kuh tu tantah

heeh, tunuh u bolih

Ka k’as t’aneh uyoli ka’an kat’aneh

Chaho kih. Chahoh a kih

Ma’ k’as lik’il

Sakapuk tu yok’ol

puleh ak’ab’ a kuneh

puleh, bineh

Tianuh hu’ unin tech

Ti’an lae. K’as kuneh

baih na wolol, ti’ yustal u hanan;

ti’ yustak yuk’ul

Le ma’ tu talah, I’tsah Noh K’uh

hela’ Chob, ka kas

t’aneh: naken t’aneh la’eh Chak Chob

heela’! Tech bin ti’ Chak Chob

Nen u bolih a chi’

pulah a k’ab a kuneh

puleh a k’ab’ a kuneh, Chob

e yan a kuneh tunun

Salak nak u lik’il

Pulah a k’ab a kuneh

pulen a k’abeh Choben!

Ti’ a ch’aik ubolih ti’ sakha’

k’as kunen Choben

Sasex, ta lakih

Sasex, ta lakilen

Sasex, ti’ a Ch’aik

u bolihmehen luchi u kih

La yak’in

La nabinen

Performer: Chan Kin Viejo

SIDE “A”

1. Brown Oats 2’02

K’ miai from San Jose la Zorra, B.C.N.

2. Student Song 3’48

Tarahumaras from Norogachi, Chih.

3. Singing to San Ildefonso 3’15

Tzeltales from San Ildefonso Tenejapa, Chis.

4. Ocotal Fork

Triqui from San Juan Copala, Oax.

5. Lord Saint Jerome

Chichimeca from la Misión, Gto.

SIDE “B”

1. Santa Fe de la Laguna 2’14

Purepecha from Sta. Fé de la Laguna, Mich.

2. Praise to the Virgin 2’53

Nahua from Zitlala, Gro.

3. Song of Shepherdesses 4’07

Otomi from San Felipe del Progreso, Estado de Mexico

4. Lucio Mu 2’53

Huichol from Sta. Ma. Ocotan, Dgo.

5. Prayer 1’26

Lacandon from Nahá, Chis.

THE RESEARCH TASKS AND COLLECTION OF MATERIALS THAT MADE THE REALIZATION OF THIS ALBUM POSSIBLE WERE ACHIEVED THANKS TO MRS. CARMEN ROMANO DE LOPEZ PORTILLO, PRESIDENT OF THE NATIONAL FUND FOR SOCIAL ACTIVITIES (FONAPAS), FOR THE FINANCING GRANTED TO THE AUDIOVISUAL ETHNOGRAPHIC ARCHIVE OF THE NATIONAL INDIGENIST INSTITUTE WITHIN THE OLLIN YOLIZTLI PROGRAM.

THE EDITION OF THESE CULTURAL REVALUATION MATERIALS WAS ALSO COVERED WITH THE GENEROUS FINANCIAL CONTRIBUTION OF VARIOUS TRADE UNIONS.

Alfredo Elias

DIRECTOR OF THE NATIONAL FUND FOR SOCIAL ACTIVITIES

Ignacio Ovalle Fernandez

GENERAL DIRECTOR OF THE NATIONAL INDIGENIST INSTITUTE

Juan Carlos Colin

HEAD OF THE AUDIOVISUAL ETHNOGRAPHIC ARCHIVE OF THE NATIONAL INDIGENIST INSTITUTE

Angel Agustin Pimentel Diaz

Jesus Herrera Pimentel

Alexander Mendez Rojas

ETHNOMUSICOLOGY UNIT: RESEARCH, EDITING AND PRODUCTION

Ethnomusicology Unit/

Jesus Sanchez Padilla

Rodolfo Sanchez Alvarado

FIELD RECORDING

Troje Workshop

DESIGN

Oscar Paoloni

PHOTOGRAPHY

Jose Manuel Pintado

WRITING AND STYLE

Tracklist:

INTERETHNIC TRADITIONAL SONGS

SIDE 1

- A1 Brown Oats 2:02

Performer(s): Nicolás Carrillo. - A2 Student Song 3:48

Performer(s): Norogachi boarding school children - A3 Song to San Ildefonso 3:15

Performer(s): Antonio Guzmán Luna and his group. - A4 Ocotal hairpin

Performer(s): Leobardo de Jesus. - A5 Lord Saint Jerome

Performer(s): Francisco López López and Andrés García

SIDE B

- B1 Santa Fe de la Laguna 2:14

Performer(s): Dimas Brothers - B2 Praise to the Virgin 2:53

Performer(s): Women of Zitlala, Guerrero. - B3 Song of Shepherdesses 4:07

Performer(s): The Dance of San Felipe de Progreso, State of Mexico. - B4 Pike Mu 2:53

Performer(s): Group of Banks of Calitique Nayarit - B5 Prayer 1:26

Performer(s): Chan Kin Viejo

Credits:

Alfredo Elias

Director of the National Fund for Social Activities

Ignacio Ovalle Fernandez

General Director of the National Indigenous Institute

Juan Carlos Colin

Head of the Audiovisual Ethnographic Archive of the National Indigenous Institute

Angel Agustin Pimentel Diaz

Jesus Herrera Pimentel

Alexander Mendez Rojas

Ethnomusicology Unit: Research, Edition and Production

Ethnomusicology Unit/

Jesus Sanchez Padilla

Rodolfo Sanchez Alvarado

field recording

Troje Workshop

Design

Oscar Paoloni

Photography

Jose Manuel Pintado

Writing and Style

Notes:

The research tasks and collection of materials that made the realization of this album possible were achieved thanks to Mrs. Carmen romano de lopez portillo, president of the national fund for social activities (fonapas), for the financing granted to the audiovisual ethnographic archive of the national indigenous institute within the ollin yoliztli program.

The edition of these cultural reassessment materials was also covered by the generous economic contribution of various union groups.

Links:

Sold For:

Highest Price:

$1250 MXMedium Price:

$1080 MXCondition:

Media Condition:

Mint (M)Sleeve Condition:

Mint (M)Other Versions:

INTERETHNIC TRADITIONAL SONGS made by the CENZONTLE label.