Info:

“Le daré todo el dinero para los indios muertos, pero un rifle para los indios vivos”.

José Vasconcelos to Manuel Gamio, as told by Miguel León Portilla

What do we mean by Mexico?

Some approaches, usually related to nationalist agendas, think of Mexican as if it was a homogeneous territory owned by all who are covered by an appellation of origin: Mexico for the Mexicans!

This idea lead us to a paradox where racist, classist attitudes and systematic violence towards cultures in resistance often comes from the same people who sing about their recent visit to Oaxaca, who talk about the capital importance to preserve traditions and how these should keep unconverted. But let’s remember Charles Rosen words, what we call tradition is a mistake commonly accepted.

To feel really Mexican is the unique requirement to feel the desire of keeping safe a tradition?

Terminology as an extension of colonial thought —prehispanic music, folk music, etc.— turns problematic when we try to discuss, for an instance, about Mexican music.

Is it possible to talk about Mexican music without instantly overshadow any other cosmogony?

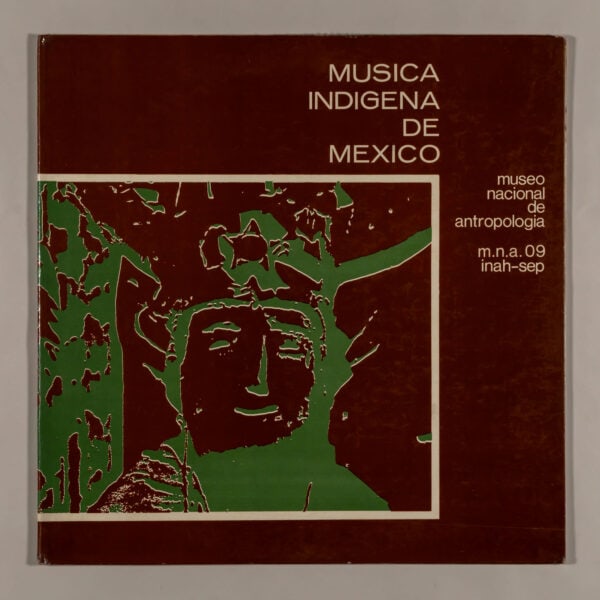

The multiple sound traditions of Mexico not only witnessed the meeting between Europe and Africa, nor can be reduced to a merely musical structure, it implies the knowledge of a context, history, geography, it is a sort of journal made by songs and music, an archive getting dissolved in a slow process, as the human body.

Many of such sound practices, which anyone could call deeply Mexican, intertwine with different festivities, rituals and habits. There is music that is played and taught the same way as Occidental music, still, it differs in its purposes. Instead of assuming the concert format as the central idea, its goal is to establish a way of communication with other spaces of reality or even for war purposes, as it is the case of Xochiyaoyotl (flower war) —music as intimidation, as a weapon. As well, for instance, it can be mentioned “La Paloma Blanca”, played by the Misioneros del Temporal or Tiemperos to get close to the spirits of the mountain temples, and the Xochipitzahuatl or “Flor Menudita”, popular song for marriages all around Puebla, Hidalgo and Tlaxcala. In addition, huapango, a capella, hip-hop, banda versions of these two particular songs can be easily found.

To fit the previous into the conception of Mexican tradition, something that identify all who live in Mexico, is just as try to fit the wrong piece into the wrong puzzle. These kind of rituals are not a piece of a homogeneous identity, despite we all feel we own the right to talk and give opinions when something seems not quite traditional nor Mexican.

Tradition is something that can pierce the pores of the present time.

Therefore, the idea of Mexican means a straightjacket for the multiplicity of cosmogonies and cultures living around the soundsphere, which, again paradoxically, has been appropriate by the mainstream national project without giving any credit.

The nation-state we talk about could be Mexico, and Peru, and Canada, and United States of America, etc., ad libitum.

To talk about Mexican music implies, as well, to talk about the history —our history— of slavery. And even though to mention it it’s a sort of beginning, there is still a long way to actually recognize the value of the contribution of African cultures, not only in the historical development of Mexican cultural products, but Mexico itself. If we look at Mexican Inquisition records, one of the first archives documenting African music, we could find allusions to Chuchumbé: a nocturnal dance celebration which every casta would attend to bunch up belly buttons; perhaps, this documents might be the first in take note of the celebration of sensuality and dissolute life of this continent, judge as harmful by de Catholic Church as a result of the questioning of the power structures implied in the dance and the music. Moreover, a short review of the development of baroque and XVII century Spanish music would suffice to perceive the complexity of rhythms is an evident African heritage.

It can be noticed that Mexican also suggest colonial issues. The appropriation of the music of cultures in resistance justified by a hypothetical “return to our common origin”. What is the difference between this and the design theft committed by cool whitexican clothes brands?

Which are the terms and conditions of the cultural exchange in such a heterogeneous territory? How power is distributed in our relations?

Modulation

In the wake of experimental music —whatever it means— concepts surrounding rare become preconceived.

Would be innocent to assume there is an exclusive definition about what is experimental. An exercise like this should be aware of the particular notions of experimentalism of the context in question.

The era of experimental music conceived as something rare is over. We are about to witness how a former laboratory become into a music genre by itself, supported by its own platforms, international, medium size and local labels, and its own press and critics thinking about its formal and technological current needs. It is not just anything.

This is not an attempt to save music form its historical sedimentation. It is, as much, an attempt to go back to a constant hunt through the whole soundsphere.

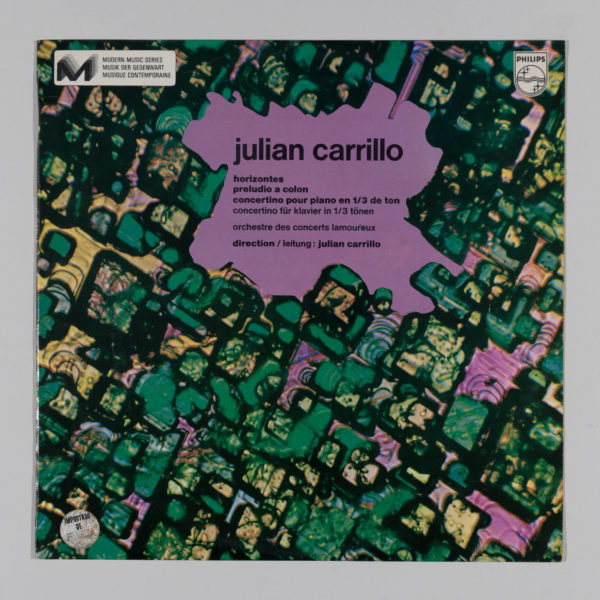

If we think about music recorded in Mexico, which pieces would be considered as rare?

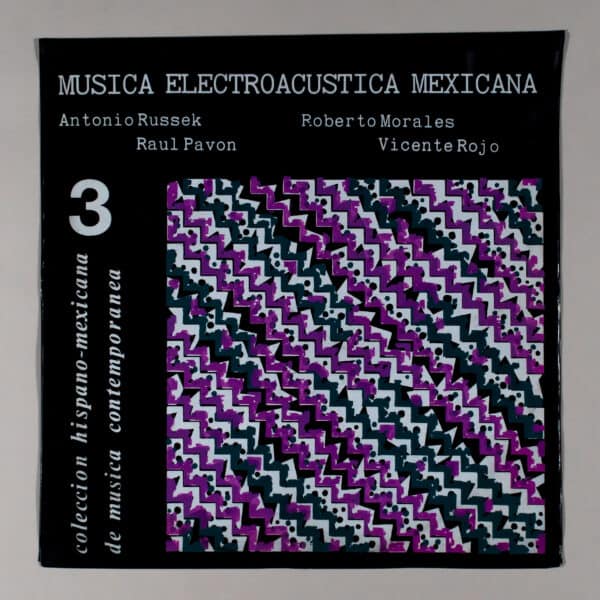

If we think about music recorded before digital era, there are many extramusical characteristics we must keep in mind in order to guide us through our path in rareness: first editions; non-commercial editions; signed editions; editions that once belong to someone in particular; the way an edition arrived at somebody hands; DIY editions; unpublished editions; unwrapped editions; editions in perfect conditions; non-musical work; interviews; archives and forgotten artists; ethnographic documentation; imported editions; handmade…

The task of create a collection around rareness is to point at its sonorous qualities, format, recording techniques, particular notions of the context, every characteristic related to sound as well as to the market values that makes something desirable.

Suddenly, we find ourselves in a crossroad.

Blue pill offers an ethic collection. An adventure quest trough the history of music genres, its protagonists, their emotional relations, as well as the sounds that characterize them. It is to identify the difference.

Red pill guide us though market values, related to speculation.

None is better than the other. Both represent positions in an imaginary chessboard made by records instead of chess pieces.

It is curious to notice the fact that many people involved in sound experimentation doesn’t identify themselves as a part of the hegemonic culture of their place of origin. What kind of identity is created by a music, apparently, without identity?

We are talking about a tribal relationship. People disperse along a virtual geography, people that share ways of thinking about sound, technology, materials, locations and rituals not necessarily appealing to the traditions of the place they are located.

Once again we found ourselves in a paradox: the construction of cultural identity in contrast to counterculture and spaces devoted to the creation of an alternative identity. If our sexuality, our class, our political position, are elements that determine the way we relate to the world, is it possible to speak of another identity, a Rare Mexican identity?

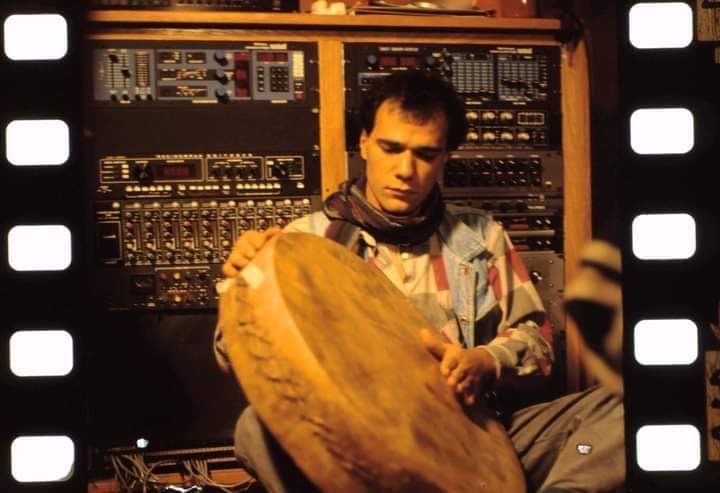

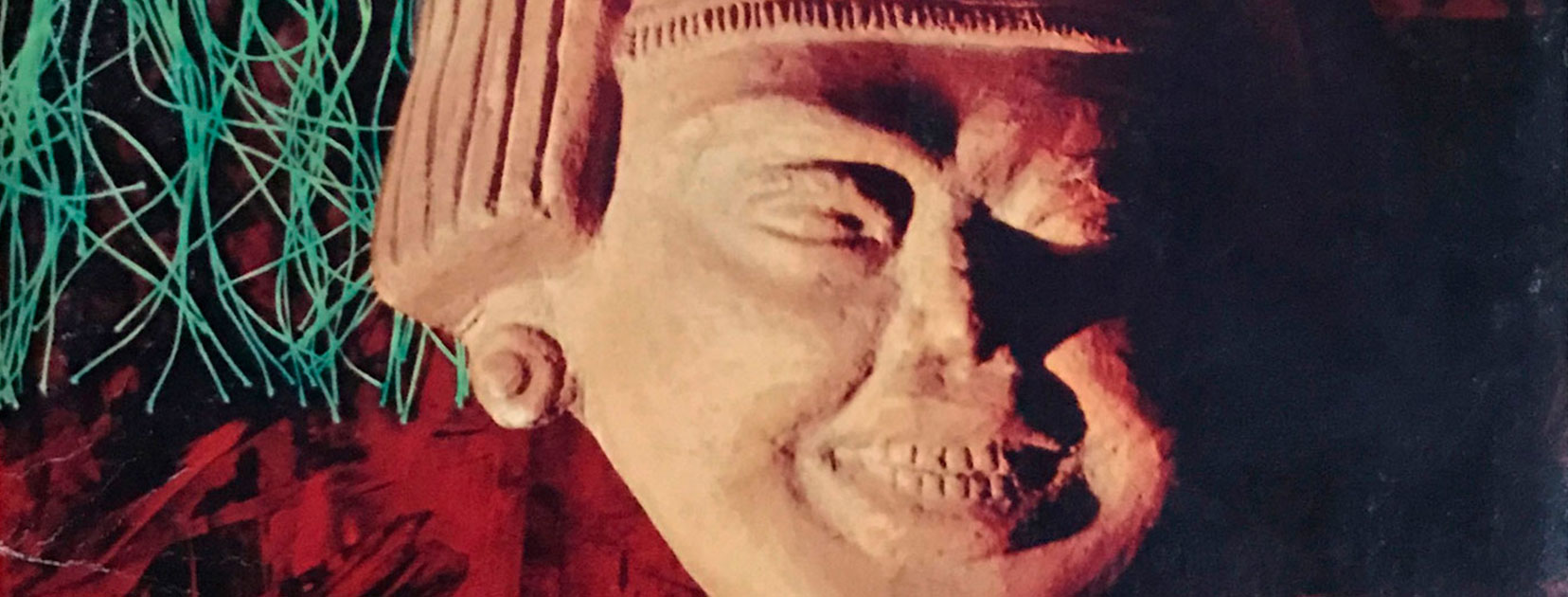

Jorge Reyes y Grupo TRIBU (Año y autor desconocido). Imagen tomada del FB de Humberto Álvarez

There is a particular phenomenon that has not been properly investigated as experimental music and Mexican counterculture: etnorock. This term covers groups as TRIBU and individuals as Jorge Reyes, Antonio Zepeda, Luis Pérez Ixonextli, Mamá Malinalli, Coyotzin, Príncipe Azteca, among others who try to return to the imaginary of the Nahuatl culture as a hyperstitional identity. Something quite similar to some afrofuturist sound fictions like Sun Ra, Parliament or Dr. Octagon —among many other examples widely studied by Kodwo Eshun—, etnorock makes use of electronic sounds emanated from the international music vanguard —something Jorge Reyes is really close to: after visiting Germany during krautrock booming, he came back and brought with him a new palette of electronic sounds and synthesizers— so as Mesoamerican objects. On the other hand, it’s possible to consider TRIBU the first to use field recordings as a part of an investigation as well as an element for music composition; meanwhile, Antonio Zepeda could be considered one of the persons who has fully explore prehispanic objects, due, perhaps, his education involving free jazz and improvisation, and his close roommate relation with Ana Ruíz and Henry West —artists behind Atrás del Cosmos.

Comala by Jorge Reyes, A la Izquierda del Colobrí by Reyes & Antonio Zepeda, or TRIBU’s Cuauhtémoc Águila Solar: fusión etnorock are futurist projects made of supersonic petates and psychedelic mushrooms. Sound projects for the future listening, without filters and definition. A return to magic and sensory faith of the world.

Tercer Mundo/ Tercer Ojo

In Necuepaliztli In Aztlan

People usually think that the closer we get to an Occidental canon, the closer we are getting to the real experimentation. People think that nothing has ever happen in Mexico, we still doing badly. Poor of us.

It is curious to notice that general appreciation usually don’t recognize projects like the described above as any sort of experimentation, they appear to be too ethnic, too native to be part of the Occidental canon. There is a blindness created by the racism deposited in the core of the Mexican social subject.

It is innocent to assume there is not such political and economic structure that supports rock music as an ideology in places like Europe or the U.S.A. Another paradox. While music is a way of living for the youth, it is a niche, and, at least in these latitudes, a reason to be shaved and abused by police. (A.C.A.B.)

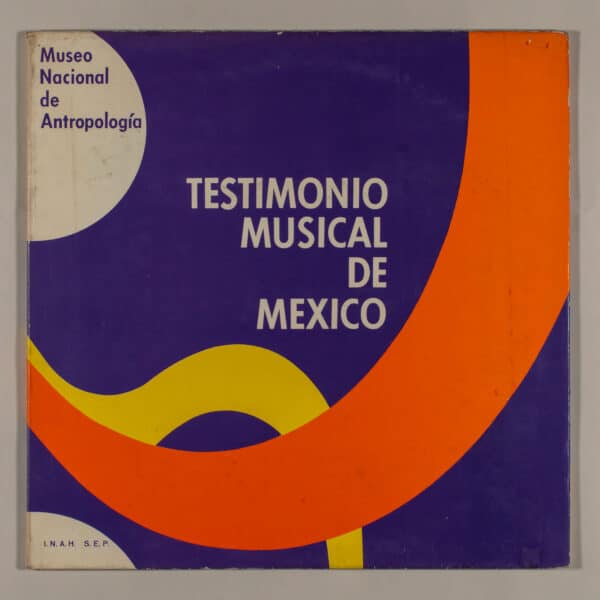

The Mexican Rarities proposal is to unveil the diverse relief of the territory named Mexico. It is not enough to return to the roots, it’s necessary to go through it. Maybe, if we question the conditions that every independent record in Mexico have had to overcome, maybe, we could learn about the value of the Historiography of the XX century Mexico.

In order to do that, to talk just about music is an understatement.