|

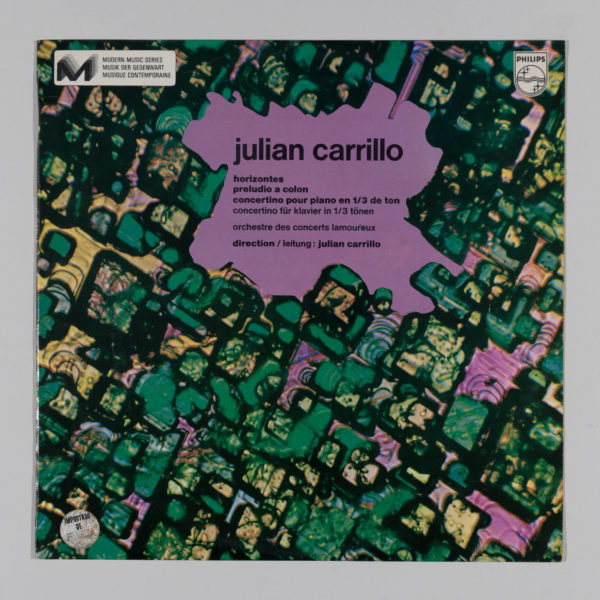

Label: FONAPAS-INI SERIES I, 1, MA-041 Released: 1980 |

Country: Mexico Genre: Folk World & Country |

Info:

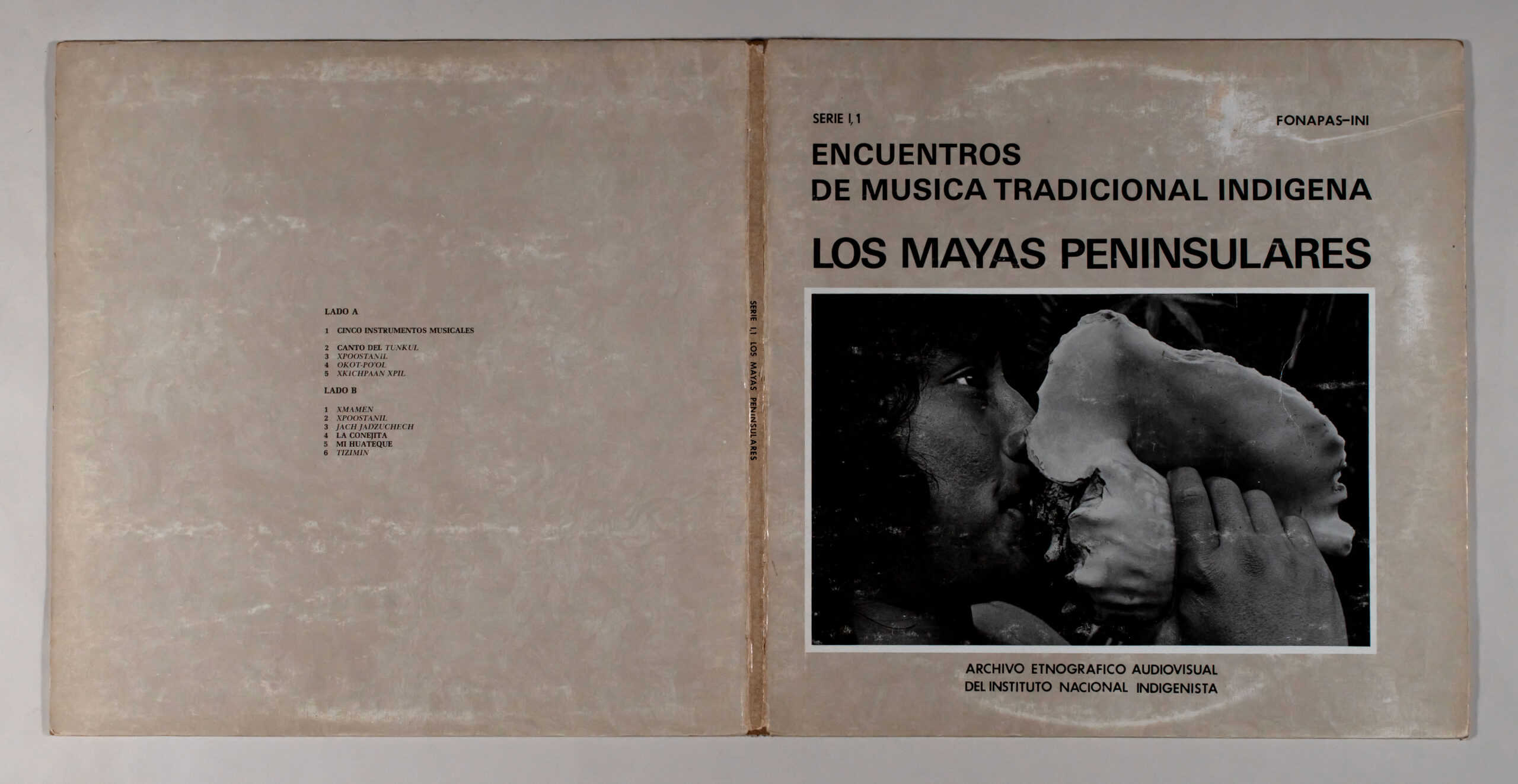

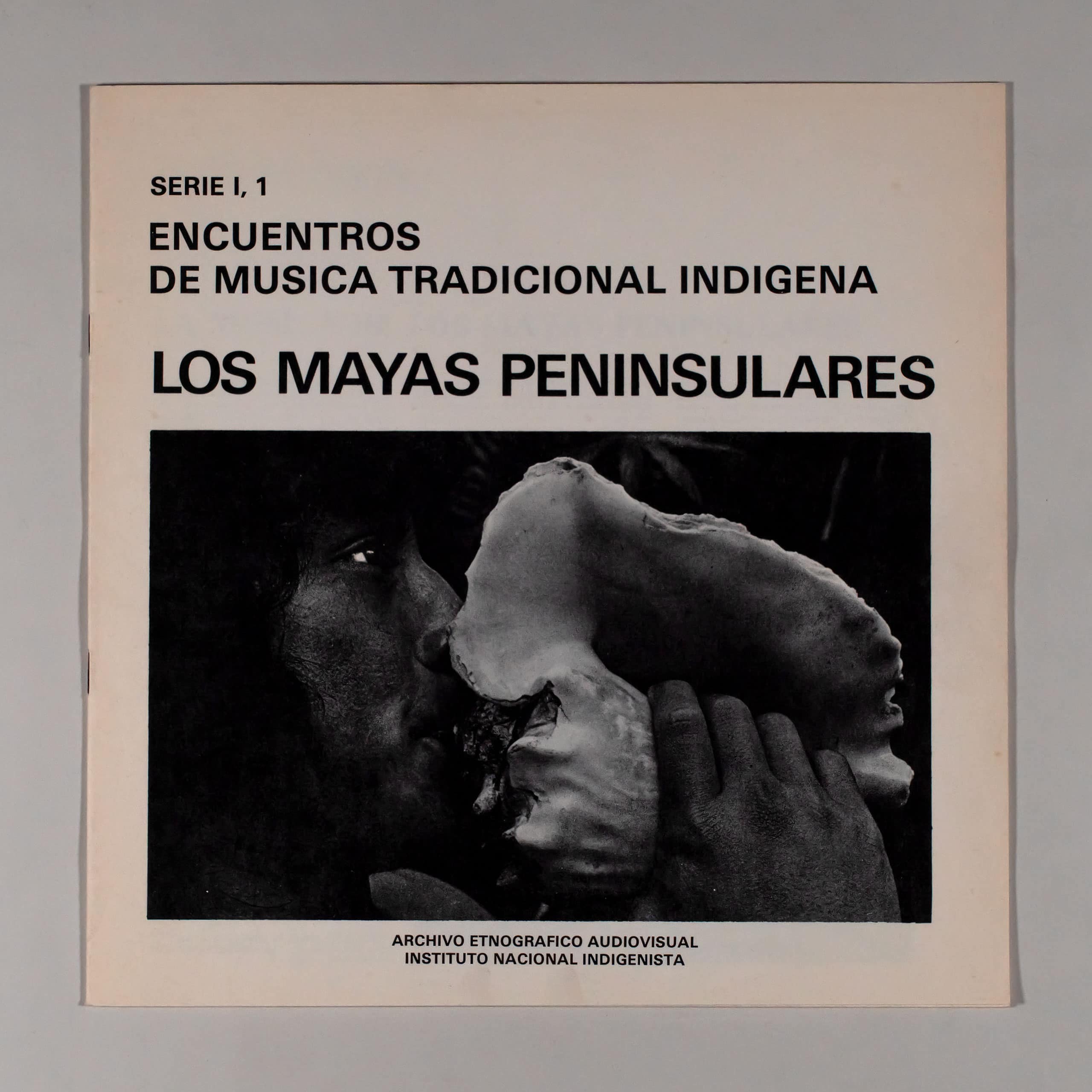

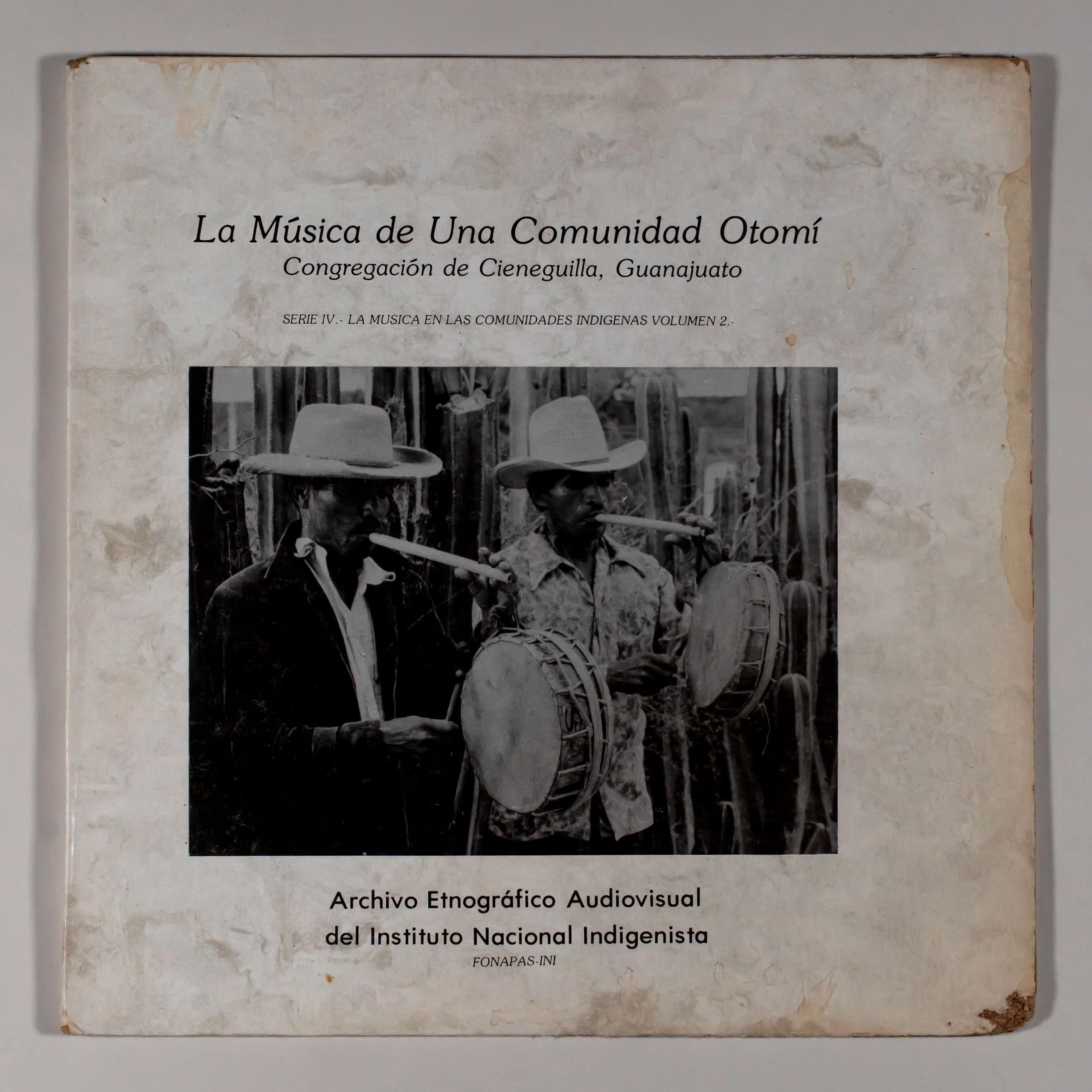

SERIES I, 1

MEETINGS OF TRADITIONAL INDIGENOUS MUSIC

THE PENINSULAR MAYAS

AUDIOVISUAL ETHNOGRAPHIC ARCHIVE NATIONAL INDIGENIST INSTITUTE

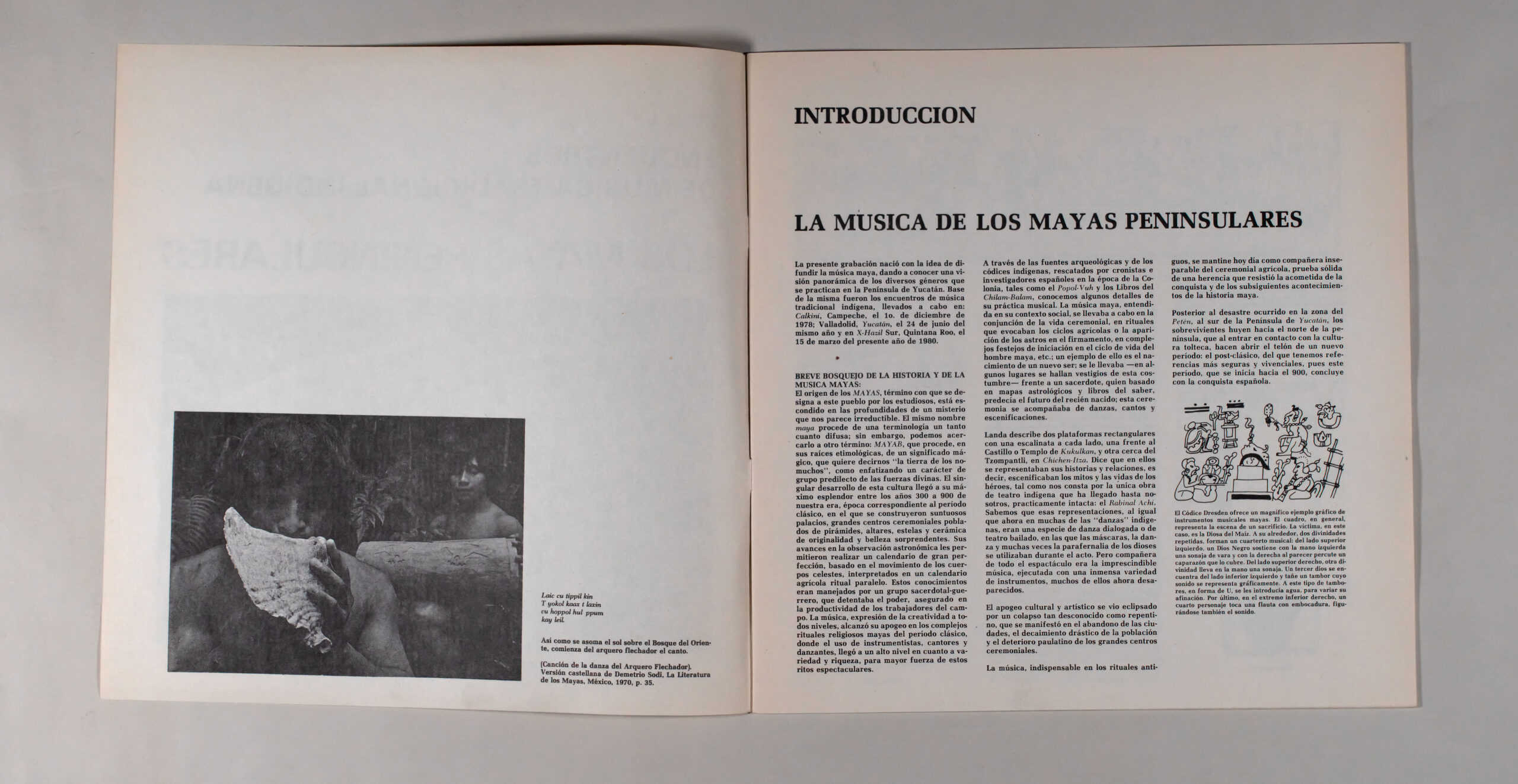

Laic cu tippil kin

T yokol kaax t laxin

cu hoppol hul ppum

kay leil

Just as the sun rises over the Forest of the East, the song of the archer with arrows begins.

(Song of the Archer Arrow Dance). Spanish version of Demetrio Sodi, The Literature of the Mayas, Mexico, 1970, p. 35.

INTRODUCTION

THE MUSIC OF THE PENINSULAR MAYAS

This recording was born with the idea of disseminating Mayan music, revealing a panoramic view of the various genres that are practiced in the Yucatan Peninsula. It was based on the meetings of traditional indigenous music, held in: Calkini, Campeche, on the 1st. December 1978; Valladolid, Yucatán, on June 24 of the same year and in X-Hazil Sur, Quintana Roo, on March 15 of this year, 1980.

BRIEF OUTLINE OF THE MAYAN HISTORY AND MUSIC:

The origin of the MAYAS, the term used by scholars to designate this people, is hidden in the depths of a mystery that seems irreducible to us. The Mayan name itself comes from a somewhat diffuse terminology; however, we can bring it closer to another term: MAYAB, which comes, in its etymological roots, from a magical meaning, which means “the land of the not-many”, as if emphasizing a character of a favorite group of divine forces. The singular development of this culture reached its maximum splendor between the years 300 and 900 of our era, a period corresponding to the classical period, in which sumptuous palaces, large ceremonial centers populated with pyramids, altars, stelae and ceramics of originality and amazing beauty. Their advances in astronomical observation allowed them to create a calendar of great perfection, based on the movement of celestial bodies, interpreted in a parallel ritual agricultural calendar. This knowledge was managed by a priestly-warrior group, which held power, assured in the productivity of field workers. Music, an expression of creativity at all levels, reached its apogee in the complex Mayan religious rituals of the classical period, where the use of instrumentalists, singers, and dancers reached a high level in terms of variety and richness, for greater force of these spectacular rites.

Through archaeological sources and indigenous codices, rescued by Spanish chroniclers and researchers in Colonial times, such as the Popol-Vuh and the Chilam-Balam Books, we know some details of his musical practice. Mayan music, understood in its social context, was carried out in conjunction with ceremonial life, in rituals that evoked agricultural cycles or the appearance of the stars in the firmament, in complex initiation festivities in the life cycle of the Mayan man, etc.; an example of this is the birth of a new being; He was taken – in some places there are vestiges of this custom – in front of a priest, who, based on astrological maps and books of knowledge, predicted the future of the newborn; this ceremony was accompanied by dances, songs and dramatizations.

Landa describes two rectangular platforms with a stairway on each side, one in front of the Castle or Temple of Kukulkan, and another near the Tzompantli, in Chichen-Itza. He says that their stories and relationships were represented in them, that is, they staged the myths and lives of the heroes, as we know from the only indigenous play that has come down to us, practically intact: the Rabinal Achi. We know that these representations, as now in many of the indigenous “dances”, were a kind of dialogic dance or danced theater, in which the masks, the dance and many times the paraphernalia of the gods were used during the act. . But a companion to the whole show was the essential music, performed with an immense variety of instruments, many of which have now disappeared.

The cultural and artistic heyday was eclipsed by a sudden and unknown collapse, which manifested itself in the abandonment of the cities, the drastic decline of the population and the gradual deterioration of the great ceremonial centers. Music, indispensable in ancient rituals, remains today as an inseparable companion of agricultural ceremonies, solid proof of a heritage that withstood the onslaught of the conquest and the subsequent events of Mayan history.

After the disaster that occurred in the Petén area, in the south of the Yucatan Peninsula, the survivors fled to the north of the peninsula, which, upon coming into contact with the Toltec culture, opened the curtain on a new period: the postclassic, of which we have more secure and experiential references, since this period, which began around 900, ended with the Spanish conquest.

The Dresden Codex offers a magnificent graphic example of Maya musical instruments. The painting, in general, represents the scene of a sacrifice. The victim, in this case, is the Maize Goddess. Around it, two repeated divinities form a musical quartet: on the upper left side, a Black God holds a stick rattle with his left hand and with his right, it seems, he strikes a shell that covers it. On the upper right side, another divinity holds a rattle in his hand. A third god is on the lower left side and beats a drum whose sound is represented graphically. Water was introduced into this type of drum, in the shape of a U, to vary its tuning. Finally, in the lower right corner, a fourth character plays a flute with a mouthpiece, also imagining the sound.

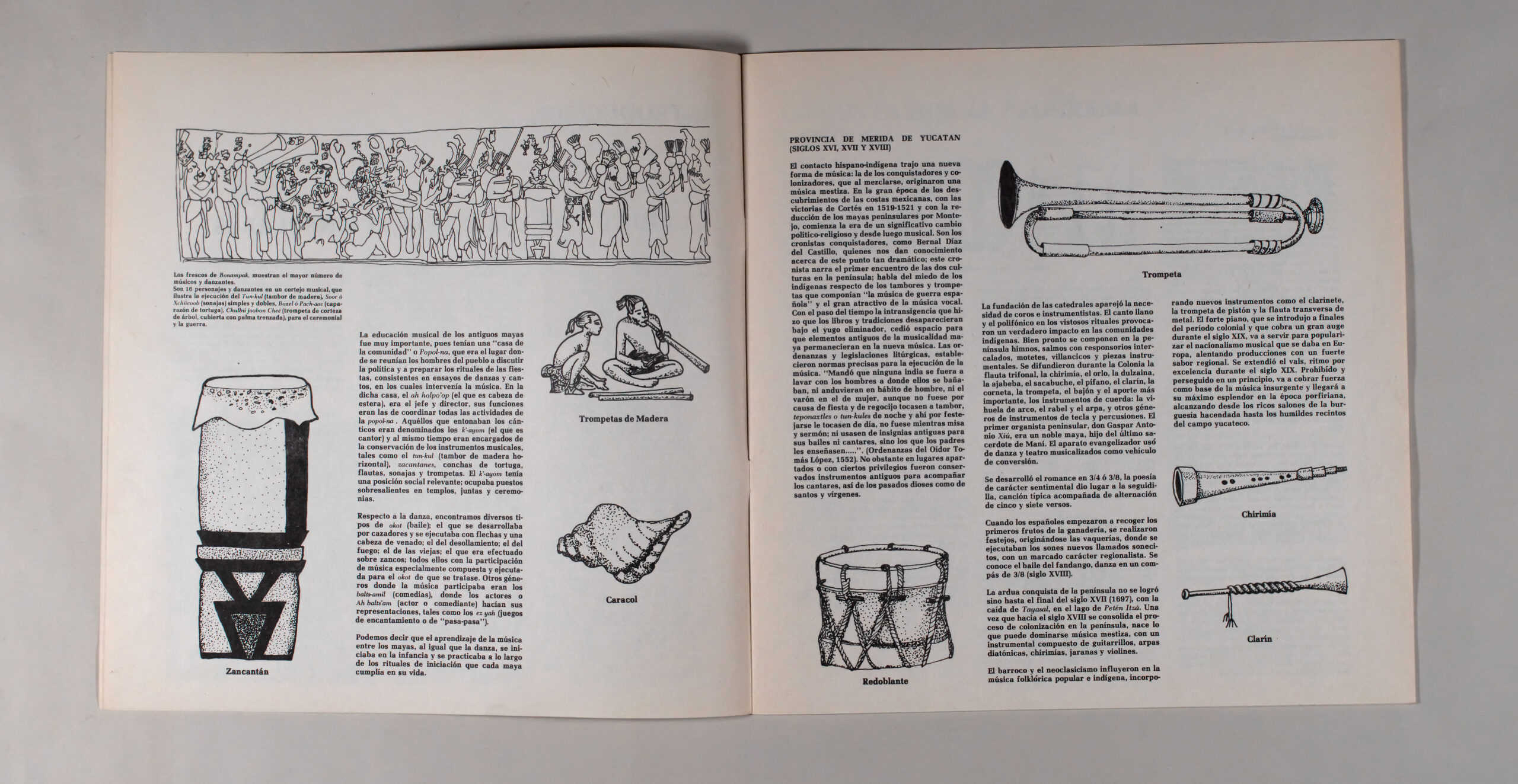

The Bonampak frescoes show the largest number of musicians and dancers. There are 16 characters and dancers in a musical procession, which illustrates the execution of the Tun-kul (wooden drum), Soor or Xchiicoob (rattles) simple and double, Boxel or Pach-aac (turtle shell), Chulbii joobon Cheé (trumpet of tree bark, covered with braided palm), for ceremonial and war.

The musical education of the ancient Maya was very important, as they had a “community house” or Popol-na, which was the place where the men of the town met to discuss politics and prepare the festival rituals, consisting of rehearsals of dances and songs, in which music intervened. In said house, the ah holpo’op (the one who is the head of the mat), was the boss and director, his functions were to coordinate all the activities of the popol-na. Those who sang the songs were called the k’-ayom (the one who is a singer) and at the same time they were in charge of the conservation of musical instruments, such as the tun-kul (horizontal wooden drum), zacantanes, shells turtle, flutes, rattles and trumpets. The k’-ayom had a relevant social position; he held prominent positions in temples, meetings, and ceremonies.

Regarding dance, we find various types of okot (dance); the one that was developed by hunters and was executed with arrows and a deer’s head; that of the flaying; that of fire; the one of the old ones; the one that was carried out on stilts; all of them with the participation of music specially composed and performed for the okot in question. Other genres where music participated were the balts-amil (comedies), where the actors or Ah balts’am (actor or comedian) made their representations, such as the ez yah (enchantment or “pass-pass” games).

We can say that the learning of music among the Maya, like dance, began in childhood and was practiced throughout the initiation rituals that each Mayan fulfilled in his life.

PROVINCE OF MERIDA DE YUCATAN (16th, 17th AND 18th CENTURIES)

The Spanish-indigenous contact brought a new form of music: that of the conquerors and colonizers, who, when mixed, originated a mestizo music. In the great age of the discoveries of the Mexican coasts, with the victories of Cortés in 1519-1521 and with the reduction of the peninsular Maya by Montejo, the era of significant political-religious and, of course, musical change began. It is the conquering chroniclers, such as Bernal Díaz del Castillo, who give us knowledge about this dramatic point; this chronicler narrates the first meeting of the two cultures in the peninsula; he talks about the natives’ fear of the drums and trumpets that made up “Spanish war music” and the great appeal of vocal music. With the passage of time, the intransigence that made books and traditions disappear under the eliminating yoke, gave way for old elements of Mayan musicality to remain in the new music. The ordinances and liturgical legislation established precise norms for the execution of music. “He ordered that no Indian woman go to wash with the men where they bathed, nor should they wear a man’s habit, nor the man in a woman’s, even if it was not for the sake of partying and rejoicing, they should play the drum, teponaxtles, or tunkules. at night and there to celebrate by day, it was not during mass and sermon; nor did they use ancient insignia for their dances or songs, but those that their parents taught them….. “. (Ordinances of Oídor Tomás López, 1552). However, in secluded places or with certain privileges, ancient instruments were preserved to accompany the songs, both of the past gods and of saints and virgins.

The foundation of the cathedrals coupled the need for choirs and instrumentalists. Plainchant and polyphonic in colorful rituals had a real impact on indigenous communities. Very soon hymns, psalms with interspersed responses, motets, carols and instrumental pieces are composed in the peninsula. During the Colony, the triphonal flute, the shawm, the orlo, the dulzaina, the ajabeba, the sackbut, the fife, the clarion, the cornet, the trumpet, the bassoon and the most important contribution, the string instruments: the vihuela de arco, the rebec and the harp, and other genres of keyboard and percussion instruments. The first peninsular organist, Don Gaspar Antonio Xiú, was a Mayan nobleman, son of the last priest of Maní. The evangelizing apparatus used musicized dance and theater as a vehicle for conversion.

The romance was developed in 3/4 6 3/8, the sentimental poetry gave rise to the seguidilla, a typical song accompanied by alternation of five and seven verses.

When the Spaniards began to gather the first fruits of the cattle ranch, festivities were held, giving rise to the dairy farms, where the new sones called sonecitos were performed, with a marked regionalist character. The dance of the fandango is known, it dances in a 3/8 compass (18th century).

The arduous conquest of the peninsula was not achieved until the end of the 17th century (1697), with the fall of Tayasal, in Lake Petén Itzá. Once the colonization process in the peninsula was consolidated around the 18th century, what can be controlled was born: mestizo music, with an instrumental made up of small guitars, diatonic harps, shawms, jaranas and violins.

Baroque and neoclassicism influenced popular and indigenous folk music, incorporating new instruments such as the clarinet, piston trumpet, and metal transverse flute. The forte piano, which was introduced at the end of the colonial period and which gained great popularity during the 19th century, will serve to popularize the musical nationalism that existed in Europe, encouraging productions with a strong regional flavor. The waltz spread, the rhythm par excellence during the 19th century. Prohibited and persecuted at first, it will gain strength as the basis of insurgent music and will reach its maximum splendor in the Porfirian era, reaching from the rich halls of the landed bourgeoisie to the humble precincts of the Yucatecan countryside.

MUSIC SINCE INDEPENDENCE

The Seville-Havana-Mérida-Veracruz-Mexico musical route constitutes a cultural basin of great interest. In the first half of the 19th century, the peninsula denoted a strong brotherhood with Andalusian, Cuban and Caribbean music. At that time, genres such as the Cubanized 6 by 8 contradanza, which today is called clave, criolla and guajira, could be heard; the 2 by 4 dance that formed the habanera dance, the danzón and some mixtures of these. The conga and the rumba were also born from the contradanza. The blacks of the French portion of the island of Santo Domingo contributed a sensual element, the cinquillo of African origin, which passed into the danzón and the bolero. Other rhythms derived from the danzón, such as the guaracha and the son montuno, appeared then, as well as new musical instruments. especially saxophones and timpani, which are being added to the instrumental.

The execution of sones with an orchestra of winds became general in the dairy farms, which achieved great popularity in rural areas.

Sentimental songs born in the Altiplano and the Bajío began to be in vogue, which had an influence on the poets and songwriters of the peninsula, strengthening the composition of short lyrical works with a love theme.

Colombia contributes the bambucos and the claves, which definitively influenced the development of the bolero. It is important to point out the passage of the Spanish and Italian theater and opera companies, which came to the peninsula via Madrid, Seville, Havana, Mérida, Veracruz and Mexico. The arias of zarzuelas and operas by Verdi or Bellini were widely heard even in the streets, by virtue of the street organs and particularly with the arrival of the phonograph. These sentimental and catchy arias also left their mark on the romantic song.

As can be seen, since the middle of the 18th century, elements of the seguidilla and the fandango have been fused, resulting in new sones of a mestizo nature.

The jarana –dance music– has its origin in the sonecitos and sones grandes of the end of the 18th century. We believe that the term jarana is derived from the word jacaranda, which means a gathering of cheerful, graceful people, and at the same time it is derived from the word jácara, which refers to a type of romance that usually recounts events of angry life, with happy, noisy and street dance music.

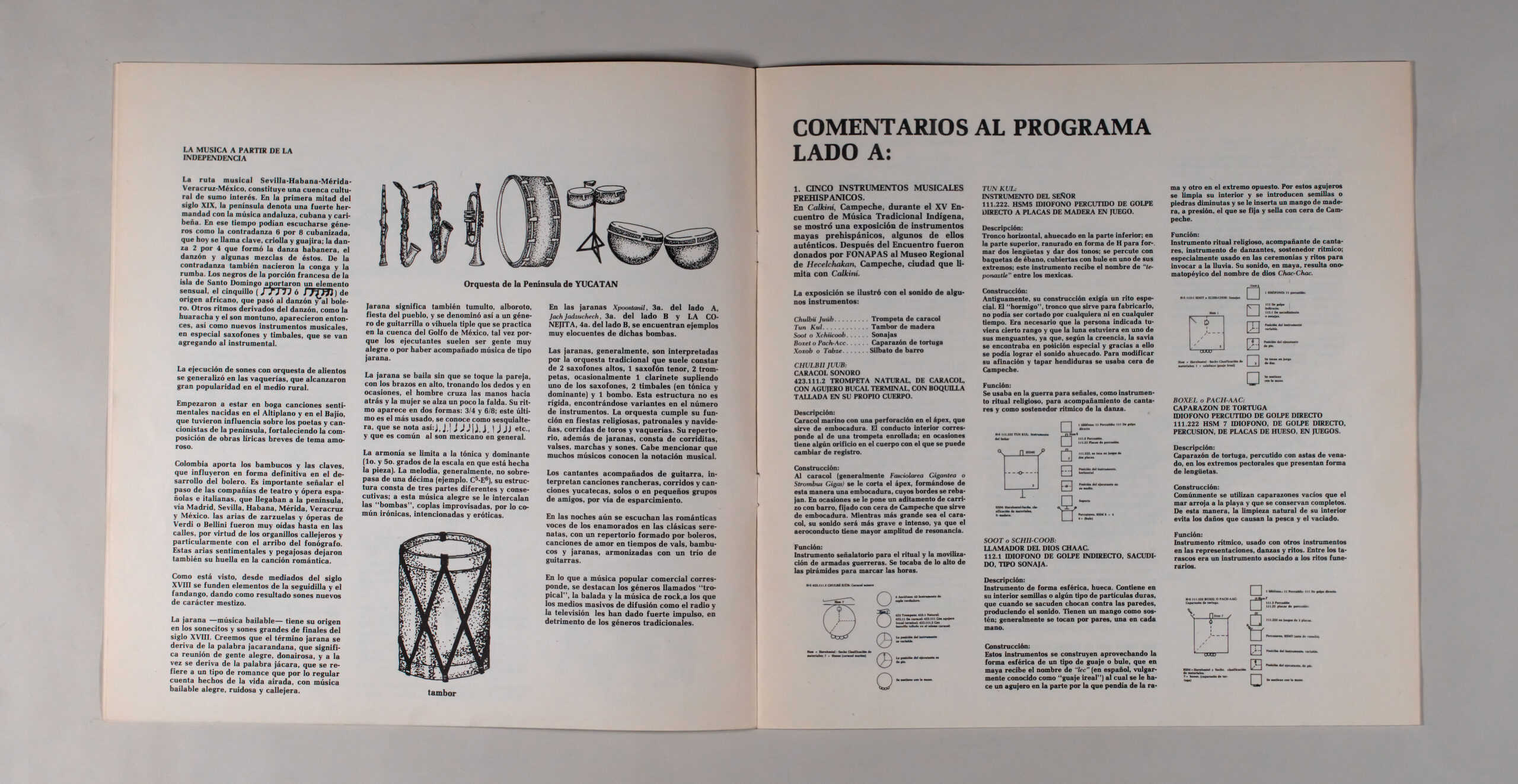

Orchestra of the YUCATAN Peninsula

Jarana also means tumult, uproar, festival of the people, and it was named like this to a genre of guitarrilla or tiple vihuela that is practiced in the Gulf of Mexico basin, perhaps because the performers are usually very happy people or because they have accompanied music by revelry type.

The jarana is danced without the partner touching, with their arms raised, snapping their fingers and sometimes, the man crosses his hands behind him and the woman raises her skirt a little. Its rhythm appears in two forms: 3/4 and 6/8; This last one is the most used, it is known as sesquialtera, which is noted like this: etc., and which is common to the Mexican son in general.

The harmony is limited to the tonic and dominant (1st and 5th degrees of the scale in which the piece is made). The melody, generally, does not exceed one tenth (example. C⁵-E⁶), its structure consists of three different and consecutive parts; this happy music is interspersed with “bombs”, improvised couplets, usually ironic, intentional and erotic.

In the jaranas Xpoostanil, 3a. from side A, Jach Jadzuchech, 3a. from side B and LA CO. NEJITA, 4a. on side B, there are very eloquent examples of such bombs.

The jaranas are generally performed by the traditional orchestra that usually consists of 2 alto saxophones, 1 tenor saxophone, 2 trumpets, occasionally 1 clarinet substituting for one of the saxophones, 2 timpani (tonic and dominant) and 1 bass drum. This structure is not rigid, finding variations in the number of instruments. The orchestra fulfills its role in religious, patron saint and Christmas festivals, bullfights and dairy farms. His repertoire, in addition to jaranas, consists of corriditas, waltzes, marches and sones. It is worth mentioning that many musicians know musical notation.

The singers, accompanied by guitar, interpret ranchera songs, corridos and Yucatecan songs, alone or in small groups of friends, by way of recreation.

At night the romantic voices of lovers are still heard in the classic serenades, with a repertoire made up of boleros, love songs in waltz times, bambucos and jaranas, harmonized with a guitar trio.

As far as commercial popular music is concerned, the so-called “tropical” genres, ballads and rock music stand out, to which the mass media such as radio and television have given a strong boost, to the detriment of the traditional genres.

COMMENTS TO THE PROGRAM

SIDE A:

1. FIVE PREHISPANIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS

In Calkiní, Campeche, during the XV Meeting of Traditional Indigenous Music, an exhibition of pre-Hispanic Mayan instruments was shown, some of them authentic. After the meeting, they were donated by FONAPAS to the Regional Museum of Hecelchakan, Campeche, a city that borders Calkiní.

The exhibition was illustrated with the sound of some instruments:

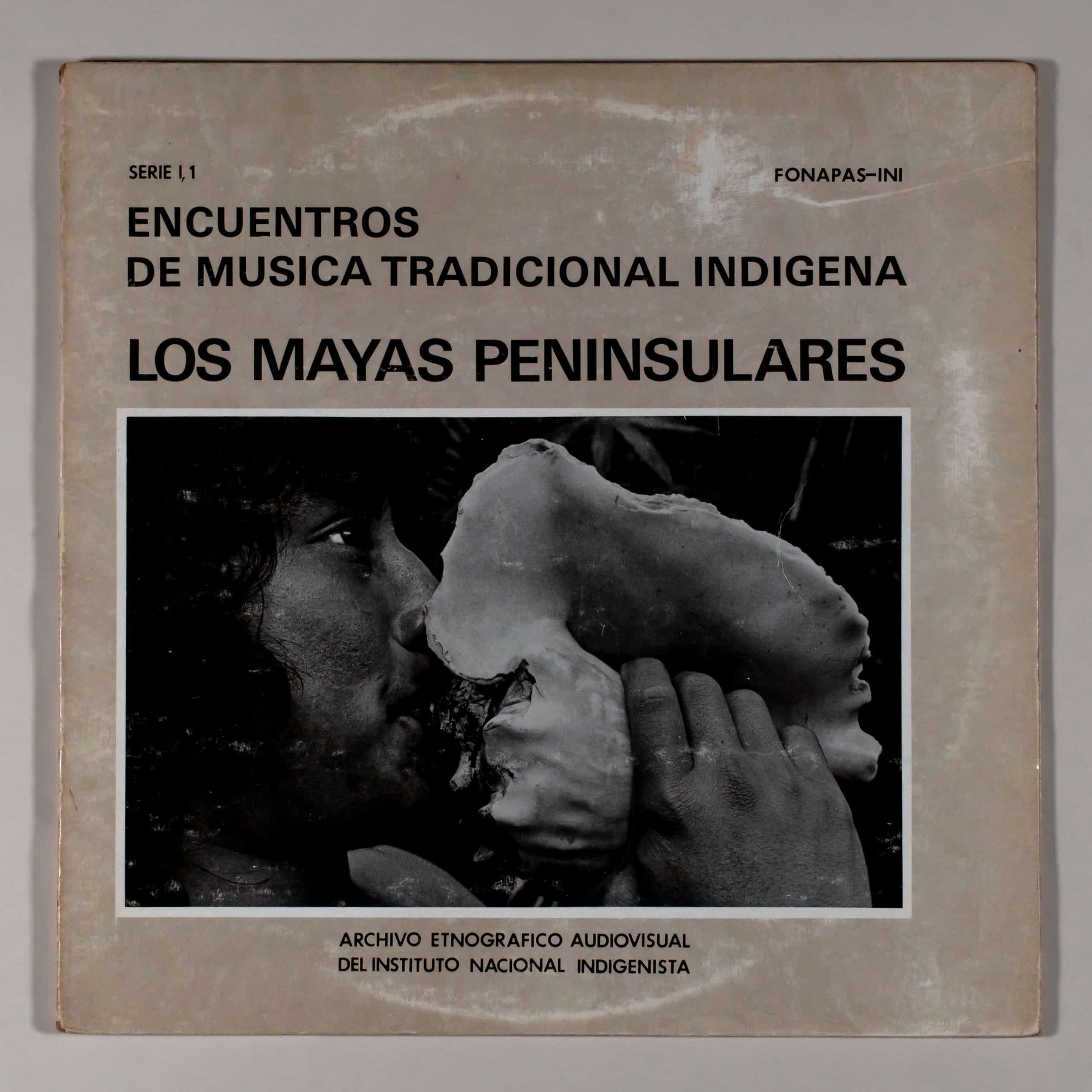

Chulbii Juúb….Snail trumpet

Tun Kul……Wooden Drum

Soot or Xchiicoob……Rattles

Boxet or Pach-Acc…….Turtle shell

Xoxob or Tabze…….Mud whistle

CHULBII JUUB:

SOUND SNAIL

423.111.2 NATURAL TRUMPET, SNAIL, WITH TERMINAL MOUTH HOLE, WITH MOUTHPIECE CARVED IN ITS OWN BODY.

Description:

Marine snail with a hole in the apex, which serves as a mouthpiece. The inner tube corresponds to that of a coiled trumpet; sometimes it has a hole in the body with which you can change register.

Construction:

The apex of the snail (generally Fasciolaria Gigantea or Strombus Gigas) is cut, thus forming a mouthpiece, whose edges are lowered. Sometimes a reed attachment with mud is added, fixed with Campeche wax that serves as a mouthpiece. The bigger the snail, the more serious and intense its sound will be, since the aero duct has a greater resonance amplitude.

Function:

Signaling instrument for the ritual and the mobilization of armed warriors. It was played from the top of the pyramids to mark the hours.

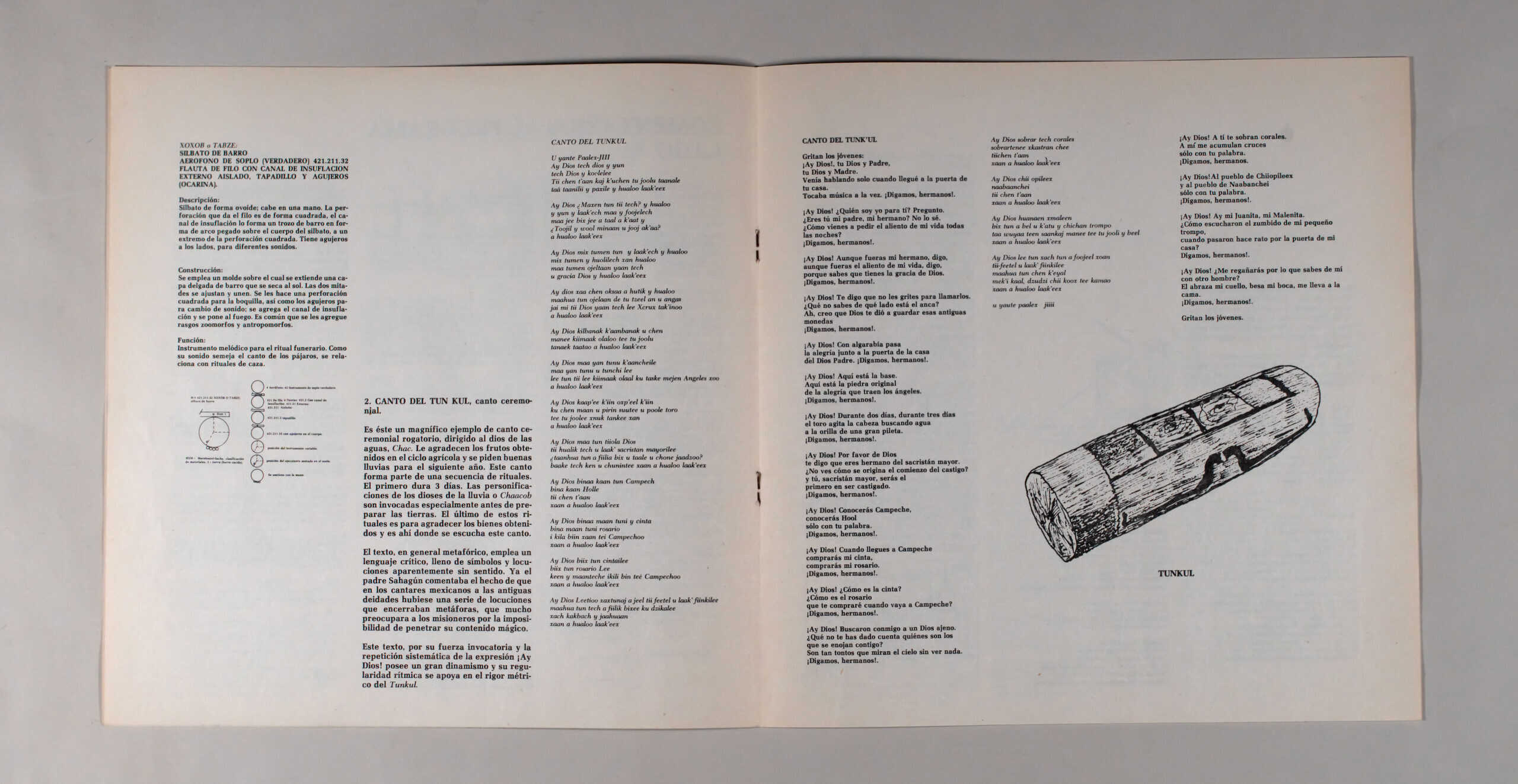

TUN KUL:

INSTRUMENT OF THE LORD

111,222. HSM5 PERCUSSION IDIOPHONE FOR DIRECT HIT ON WOODEN PLATES IN PLAY.

Description:

Horizontal trunk, hollowed out at the bottom; at the top, grooved in the shape of an H to form two tabs and give two tones; it is struck with ebony drumsticks, covered with rubber at one end; This instrument receives the name of “teponaztle” among the Mexicas.

Construction:

In the past, its construction required a special rite. The “ant”, the trunk used to make it, could not be cut by anyone or at any time. It was necessary that the indicated person had a certain rank and that the moon was in one of its waning, since, according to the belief, the sap was in a special position and thanks to this the hollowed-out sound could be achieved. Campeche wax was used to modify its tuning and cover cracks.

Function:

It was used in war for signals, as a religious ritual instrument, to accompany songs and as a rhythmic support for dance.

SOOT o SCHII-COOB:

CALLER OF THE GOD CHAAC.

112.1 IDIOPHONE OF INDIRECT SHOCK, SHAKEN, RATTLE TYPE.

Description:

Instrument spherical, hollow. It contains inside seeds or some kind of hard particles, which when shaken hit the walls, producing the sound. They have a handle as a support; they are usually played in pairs, one in each hand.

Construction:

These instruments are built taking advantage of the spherical shape of a type of gourd or bule, which in Maya is called “lec” (in Spanish, commonly known as “irreal gourd”), to which a hole is made in the part where the which hung from the branch and another at the opposite end. Through these holes its interior is cleaned and seeds or tiny stones are introduced and a wooden handle is inserted, under pressure, which is fixed and sealed with Campeche wax.

Function:

Religious ritual instrument, accompanist of songs, instrument of dancers, rhythmic sustainer; especially used in ceremonies and rites to invoke the rain. Its sound, in Maya, is onomatopoeic of the name of the god Chac-Chac.

BOXEL o PACH-AAC:

DIRECT HIT IDIOPHONE TURTLE SHELL

111.222 HSM 7 IDIOPHONO, DIRECT STRIKE, PERCUSSION, MADE OF BONE PLATES, IN SETS.

Description:

Turtle shell, percussed with deer antlers, on the pectoral ends that have the shape of tabs.

Construction:

Empty shells that the sea throws up on the beach and which are preserved complete are commonly used. In this way, the natural cleaning of its interior prevents damage caused by fishing and emptying.

Function:

Rhythmic instrument, used with other instruments in performances, dances and rites. Among the Tarascans it was an instrument associated with funeral rites.

XOXOB o TABZE:

CLAY WHISTLE AEROPHONE BLOWING (REAL) 421.211.32 EDGE FLUTE WITH ISOLATED EXTERNAL INSUFLATION CHANNEL, COVER AND HOLES (OCARINA).

Description:

Ovoid shaped whistle; fits in one hand The perforation that gives the edge is square, the insufflation channel is formed by a piece of clay in the shape of an arc glued on the body of the whistle, at one end of the square perforation. It has holes on the sides, for different sounds.

Construction:

A mold is used on which a thin layer of clay is spread and dried in the sun. The two halves fit together. A square hole is made for the mouthpiece, as well as the holes for changing the sound; the insufflation channel is added and it is put on the fire. It is common for zoomorphic and anthropomorphic features to be added to them.

Function:

Melodic instrument for the funeral ritual. As its sound is similar to the song of birds, it is related to hunting rituals.

2. SONG OF THE TUN KUL, ceremonial song.

This is a magnificent example of a ceremonial prayer song, addressed to the god of the waters, Chac. They thank him for the fruits obtained in the agricultural cycle and ask him for good rains for the following year. This chant is part of a sequence of rituals. The first lasts 3 days. The personifications of the rain gods or Chaacob are specially invoked before preparing the land. The last of these rituals is to give thanks for the goods obtained and that is where this song is heard.

The text, generally metaphorical, uses a critical language, full of symbols and phrases that appear to be meaningless. Father Sahagún already commented on the fact that in the Mexican songs to the ancient deities there was a series of locutions that contained metaphors, which greatly worried the missionaries due to the impossibility of penetrating their magical content.

This text, due to its invocative force and the systematic repetition of the expression ¡Ay Dios! It has great dynamism and its rhythmic regularity is supported by the metrical rigor of the Tunkul.

SONG OF THE TUNKUL

U yante Paalex-JIII

Ay Dios tech dios y yun

tech Dios y koelelee

Ti chen t’aan kaj k’uchen tu joolu taanale

taá taanilii y paxile y hualoo laak’eex

Ay Dios Maxen tun tii tech? y hualoo

y yun y laak’ech maa y foojelech

maa jee bix jee a taal a k’aat y

¿Toojil y wool minaan u jooj ak’aa?

a hualoo laak’eex

Ay Dios mix tumen tun y laak’ech y hualoo

mix tumen y huolilech xan hualoo

maa tumen ojeltaan yaan tech

u gracia Dios y hualoo laak’eex

Ay dios xaa chen oksaa a hutik y hualoo

maahua tun ojelaan de tu tzeel an u angas

jai mi tii Dios yaan tech lee Xcrux tak’inoo

a hualoo laak’eex

Ay Dios kilbanak k’aanbanak u chen

manee kiimaak olaloo tee tu joolu

tanaek taatao a hualoo laak’eex

Ay Dios maa yan tunu k’aancheile

maa yan tunu u tunchi lee

lee tun tii lee kiimaak olaal ku taske mejen Angeles xoo

a hualoo laak’eex

Ay Dios kaap’ee k’iin oxp’eel k’iin

ku chen maan u pirin suutee u poole toro

tee tu joolee xnuk tankee xan

a hualoo laak’eex

Ay Dios maa tun tiiola Dios

tii hualik tech u laak’ sacristan mayorilee

¿taanhua tun a fiilia bix u taale u chone jaadzoo?

baake tech ken u chunintee xaan a hualoo laak’eex

Ay Dios binaa kaan tun Campech

bina kaan Holle

tii chen t’aan

xaan a hualoo laak’eex

Ay Dios binaa maan tuni y cinta

bina maan tuni rosario

i kila biin xaan tei Campechoo

xaan a hualoo laak’eex

Ay Dios biix tun cintailee

biix tun rosario Lee

keen y maanteche ikili bin teé Campechoo

zaan a hualoo laak’eex

Ay Dios Leetioo xaxtunaj a jeel tii feetel u laak’ fiinkilee

maahua tun tech a fiilik bixee ku dzikalee

xach kakbach y jaahuaan

xuan a hualoo laak’eex

Ay Dios sobrar tech corales

sobrartenee xkastran chee

tüchen t’aan

xaan a hualoo laakeex

Ay Dios chii opileex

naabaanchei

tii chen t’aan

xaan a hualoo laak’eex

Ay Dios huanaen xmaleen

bix tun a bel u k’atu y chichan trompo

taa wuyaa teen saankaj manee tee tu jooli y beel

xaan a hualoo laak’eex

Ay Dios lee tun xach tun a foojeel xoan

tii-feetel u laak’ fiinkilee

maahua tun chen k’eyal

mek’i kaal, dzudzi chii koox tee kamao

xaan a hualoo laak’eex

u yaute paalex jiiii

SONG OF THE TUNKUL

The youths shout:

Oh God, your God and Father,

your God and Mother.

He was talking alone when I got to the door of

your house.

He played music at the same time. Let’s say, brothers!

Oh my God! Who I am for you? Asked.

Are you my father, my brother? Don’t know.

How do you come to ask for the breath of my life all

the nights?

Let’s say, brothers!

Oh my God! Even if you were my brother, I say,

Even if you were the breath of my life, I say,

because you know you have the grace of God.

Let’s say, brothers!

Oh my God! I tell you don’t yell at them to call them.

Don’t you know which side the haunch is on?

Ah, I think that God gave you to keep those old

coins

Let’s say, brothers!

Oh my God! with merriment passes

joy at the door of the house

of God the Father. Let’s say, brothers!

Oh my God! Here is the base.

Here is the original stone

of the joy that angels bring.

Let’s say, brothers!

Oh my God! For two days, for three days

the bull shakes his head looking for water

on the edge of a large pool.

Let’s say, brothers!

Oh my God! please god

I tell you that you are the brother of the elder sacristan.

Don’t you see how the beginning of punishment originates?

and you, senior sacristan, will be the

first to be punished.

Let’s say, brothers!

Oh my God! You will know Campeche,

you will meet hool

only with your word.

Let’s say, brothers!

Oh my God! When you arrive in Campeche

you will buy my tape,

you will buy my rosary

Let’s say, brothers!

Oh my God! How is the tape?

How is the rosary

What will I buy him when I go to Campeche?

Let’s say, brothers!

Oh my God! They searched with me for an alien God.

What have you not realized who are the

who are mad at you?

They are so stupid that they look at the sky without seeing anything.

Let’s say brothers!

Oh my God! You have too many corals.

I accumulate crosses

only with your word.

Let’s say brothers!

Oh my God! To the town of Chiiopileex

and the people of Naabanchei

only with your word.

Let’s say, brothers!

Oh my God! Oh my Juanita, my Malenita.

How did you hear my little buzz

top,

when they passed by my door a while ago

home?

Let’s say, brothers!

Oh my God! Will you scold me for what you know about me

with another man?

He hugs my neck, kisses my mouth, he takes me to the

bed.

Let’s say, brothers!

The youths shout.

3. XPOOSTANIL (makeup), revelry 3/4.

This interesting example of a jarana in 3/4 time, performed by a single singer who alternately glosses interludes with the harmonica, corresponds to a genre of jaranas that contain elements of social criticism, as in this case the exaggerated use of makeup.

La bomba, picaresque and humorous verse that is interspersed in the piece. stopping the musical discourse, has here the function of ridiculing some attitudes of young people.

“XPOOSTANIL”

Le tune xch’upalaloboó tu taloó lé chaán tung

Saak’aán tunu u chichan okoó biné

Le’xmamadziloboó tu b’noó tu pak’choobin

Pak’ach, pak’ach, pak’ach

Tu pak’achoó tun tu jantikoó tuné

U tialu yuúlex bakeraoboo

Lét xch’upalaoboó tu dzaik tunu u polvoi tun u gichoo

Yeetel tun u pintalabio, yeetel u colorete

yeetel u xpoostanil u yichoó.

MAKE-UP

Women come to enjoy

They feel itchy in their little feet.

The mothers are making tortillas.

Making, making, making tortillas

eating and making tortillas

For the jaraneras that arrive.

All the women make up their faces.

They also paint their lips and use rouge

And they exaggerate with so much dust in the face.

Bomb

Lé ká luú tune xch’upaló

Jakchaá tie lé lúmoo

ká lik’ yaakabee

Maá letie echeetaab si no ke luúkoo

U pool xpoostanchai u dzeel tii tu jool tux luú boó

Koox dzaik u laá jump’el música maestro

Tumen leloó Kimak-ol baax ka betik eteel

Lé tune xtatakmek’o ti mix baá tií usartabi

toán tun u mansikoó tun u k’ab lé xch’upalalabod

Yeetel tun u cruzartik tun u yook’otoó

Ken tuún u tiaál u yook’otobeé

Lé tuné xch’upalaloboó tu tatakmek’oó

Lé ká taloó tune lé xmamadzilobeé

Tu cheetitoo baax ku beetik u hijao bin

Yeetel y rebozo azul, yeetel u terno azul,

Yeetel u cinta azul, yeetel u tup de dublé.

BOMB

when the girl fell

she to the ground she came to give

and she on the spot she stopped.

They didn’t laugh at his fall

but because of the dust that she stuck to it

from the hole where she fell.

Let’s play music, teacher,

because what you do is joy with us!.

But the violent hugs

they were not used at all.

Girls hold hands

and they cross between the dance.

When are they going to dance?

they give violent hugs.

When the mothers arrived

they laughed to see what their children do.

With his blue shawl and his blue suit

With her blue ribbon and her filigree earring.

4. OKOT-POOL (head dance), dance 4/4.

In the peninsula there are mayordomias known as “societies”. They are organized especially for the novenas and patronal festivals of the Saints. One of the partners is chosen to raise a piglet, which the following year will have grown enough to be eaten. The pig is slaughtered, its body sold, and its head placed in a large basket. This head is surrounded with bread, a bottle of liquor and fruit, the whole is decorated with colored ribbons, all the members in the entourage make a procession headed by a group carrying banners; then the musicians, with 2 violins, a bass drum and a snare, precede them. In Calkiní there is no one who plays the violin, so they improvise instruments with combs covered with paper or oilcloth, put them on their lips and sing the melody. They are accompanied by guitars.

The rest of the partners and the people who want to dance with the pig’s head raised, go through the main streets of the town and arrive at the house of another partner who must live as far away as possible from the first one so that the act lasts longer. Upon arrival, the last prayer is performed, which culminates with a dance with an orchestra, where revelry is danced, while the pig’s head is cooked to serve as a banquet for the guests. This example is interpreted with the classic instrumental for this type of dance, especially in Quintana Roo: violin, bass drum and a snare drum, direct hit membranophones, cylindrical tubular with two skins (211.212), one large and one small. These instruments are sacred and are kept in the church (fig.).

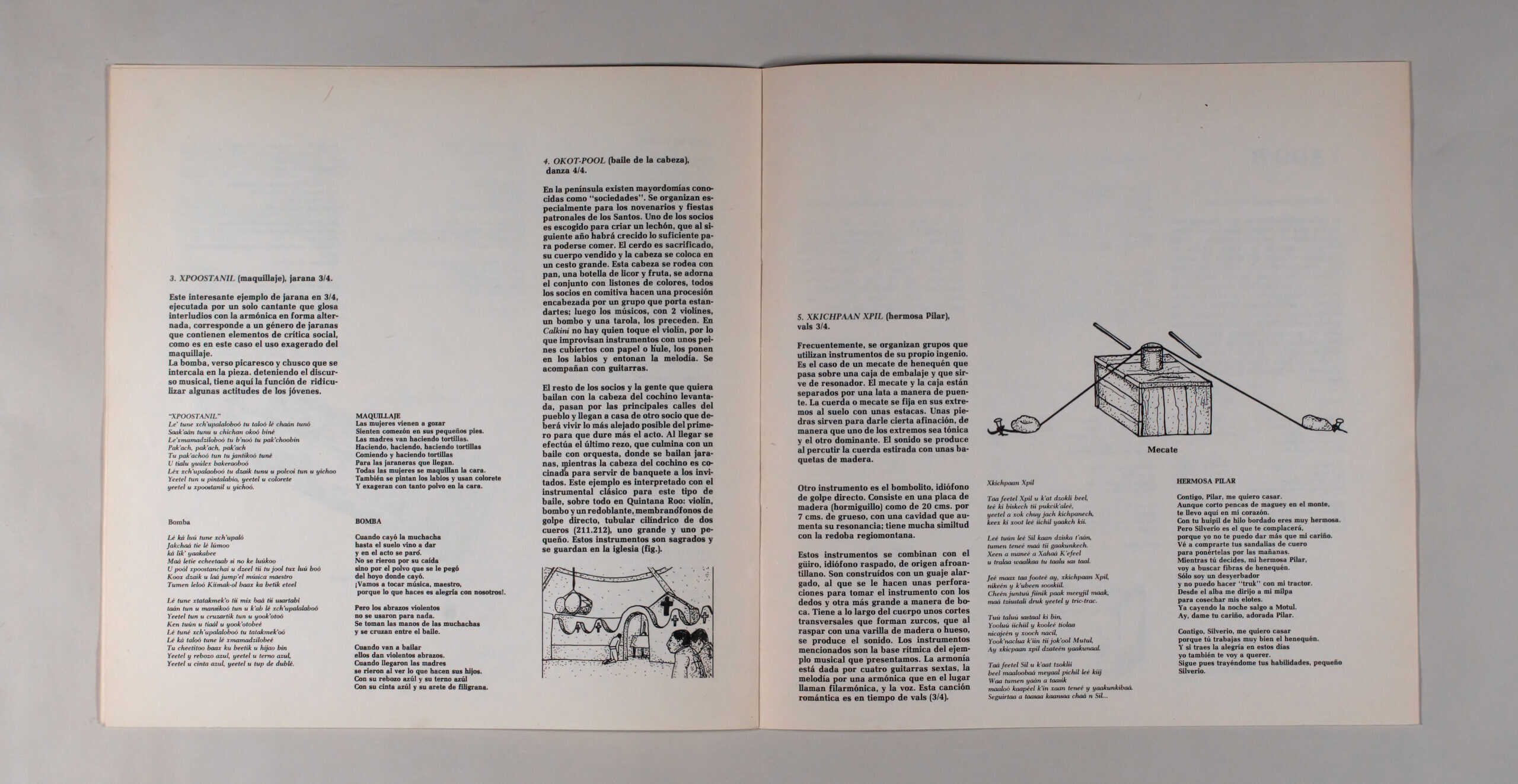

5. XKICHPAAN XPIL (beautiful Pilar), waltz 3/4.

Frequently, groups are organized that use instruments of their own ingenuity. This is the case of a henequen rope that passes over a packing box and serves as a resonator. The rope and the box are separated by a can as a bridge. The rope or mecate is fixed at its ends to the ground with stakes. Some stones are used to give it a certain tuning, so that one end is tonic and the other is dominant. The sound is produced by hitting the stretched string with wooden drumsticks.

Another instrument is the bombolito, a direct hit idiophone. It consists of a wooden plate (hormiguillo) about 20 cms. by 7 cm. thick, with a cavity that increases its resonance; It is very similar to the Monterrey redoba.

These instruments are combined with the güiro, a scratched idiophone of Afro-Antillean origin. They are built with an elongated gourd, to which some perforations are made to hold the instrument with the fingers and another larger one as a mouth. It has transversal cuts along the body that form grooves, which when scraped with a wooden or bone rod, produces a sound. The mentioned instruments are the rhythmic base of the musical example that we present. The harmony melody by a harmonica that in the place is given by four sixth guitars, they call it philharmonic, and the voice. This romantic song is in waltz time (3/4).

Xkichpaan Xpil

Taa feetel Xpil u k’at dzokli beel,

teé ki biskech tii pukcik’aleé,

yeetel a xok chuy jach kichpanech,

keex ki xoot leé ichil yaakch kii.

Leé tuún leé Sil kaan dziska t’aán,

tumen teneé maá tii gaakunkech.

Xeen a maneé a Xahaá K’efeel

u tralaa waalkaa tu taalu sas taal.

Jeé maax taa footeé ay, xkichpaan Xpil,

nikeén y k’ubeen sooskiil.

Cheen juntuú fiinik paak meeyjil maak,

maá tziustali druk yeetel y tric-trac.

Tuú taluú sastaal ki bin,

Yooluú ichiil y kooleé tíolaa

nicajeén y xooch nacil,

Yook’naclua k’iin tii jok’ool Mutul,

Ay xkicpaan xpil dzateén yaakunaal.

Taá feetel Sil u k’aat tzoklii

beel maaloobaá meyaal pichil leé kiij

Waa tumen yaán a taasik

maaloo kaapéel k’in xaan teneé y yaakunkibaá.

Seguirtaa a taasaa kaansaa chaá n Sil…

BEAUTIFUL PILLAR

With you, Pilar, I want to get married.

Although I cut maguey leaves in the mountains,

I carry you here in my heart.

With your embroidered thread huipil you are very beautiful.

But Silverio is the one who will please you,

Because I can’t give you more than my love.

Go buy your leather sandals

to put them on in the morning.

While you decide, my beautiful Pilar,

I’m going to look for henequen fibers.

I’m just a weeder

And I can’t “truk” my tractor.

Since dawn I go to my milpa

to harvest my corn.

As night falls I go out to Motul.

Oh, give me your love, beloved Pilar.

With you, Silverio, I want to get married

because you work very well with henequen.

And if you bring joy these days

I’m going to love you too.

So keep bringing me your skills, little one.

Silverio.

SIDE B

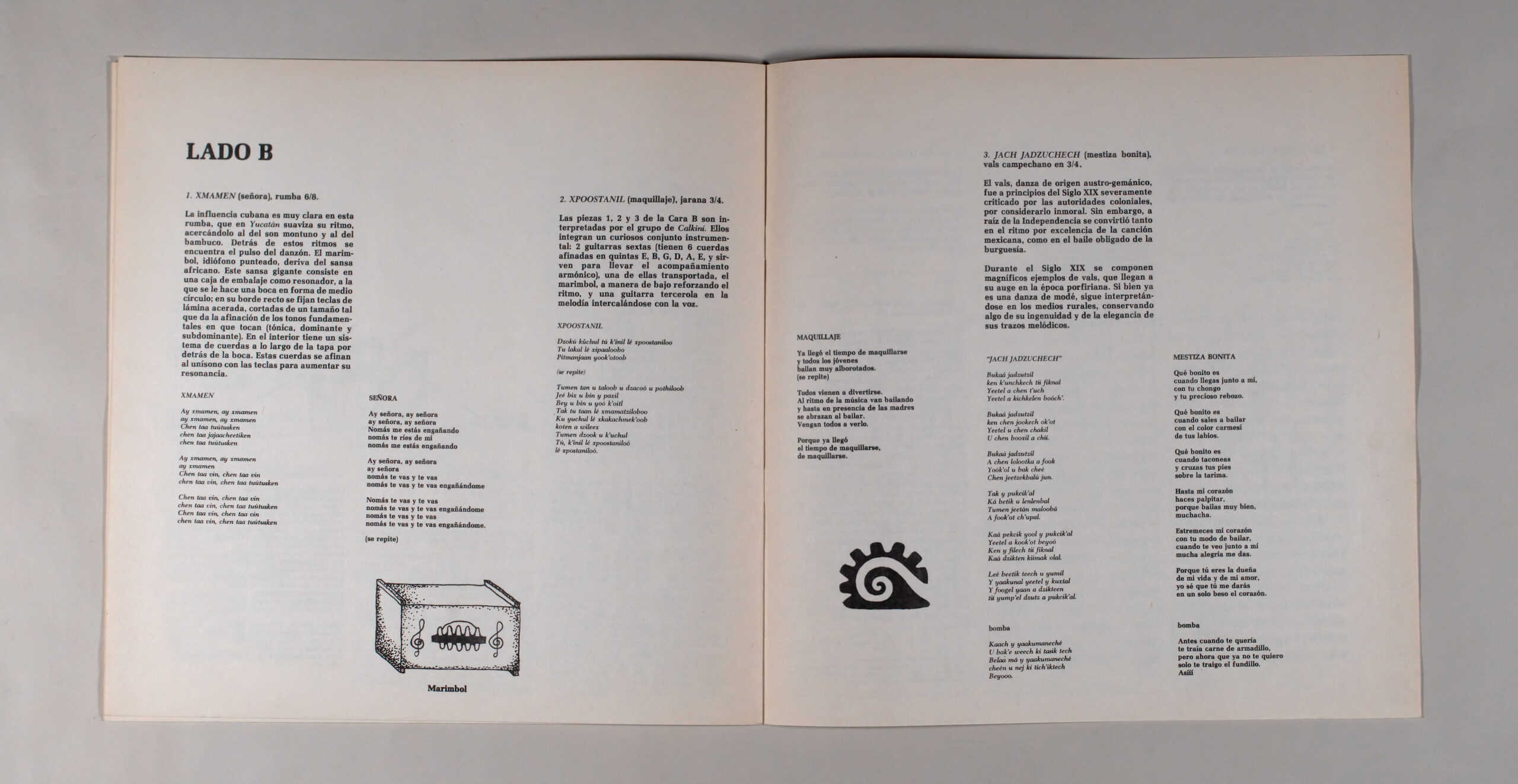

1. XMAMEN (lady), rumba 6/8.

The Cuban influence is very clear in this rumba, which in Yucatán softens its rhythm, bringing it closer to that of son montuno and bambuco. Behind these rhythms is the pulse of the danzón. The marimbol, a dotted idiophone, derives from the African sansa. This giant sansa consists of a packing box as a resonator, to which a mouth is made in the shape of a half circle; On its straight edge, steel plate keys are fixed, cut in such a size that it gives the tuning of the fundamental tones in which they play (tonic, dominant and subdominant). Inside it has a system of strings along the lid behind the soundhole. These strings are tuned in unison with the keys to increase their resonance.

XMAMEN

Ay xmamen, ay xmamen

ay xmamen, ay xmamen

Chen taa tuútusken

chen taa jajaacheetiken

chen taa tuútusken

Ay xmamen, ay xmamen

ay xmamen

Chen taa vin, chen taa vin

chen taa vin, chen taa tuútusken

Chen taa vin, chen taa vin

chen taa vin, chen taa tuútusken

Chen taa vin, chen taa vin

chen taa vin, chen taa tuútusken

MISTRESS

oh lady, oh lady

oh lady, oh lady

you’re just cheating on me

you just laugh at me

you’re just cheating on me

oh lady, oh lady

oh lady

you just go and you go

you just go and you go cheating on me

you just go and you go

you just go and you go cheating on me

you just go and you go

you just go and you go cheating on me.

(is repeated)

2. XPOOSTANIL (makeup), revelry 3/4.

Pieces 1, 2 and 3 of Side B are performed by the Calkiní group. They make up a curious instrumental ensemble: 2 sixth guitars (they have 6 strings tuned in fifths E, B, G, D, A, E, and serve to carry the harmonic accompaniment), one of them transported, the marimbol, in the manner bass reinforcing the rhythm, and a tercerola guitar in the melody interspersed with the voice.

XPOOSTANIL

Dzokú kůchul tú k’inil lé xpoostaniloo

Tu lakal lé xipaaloobo

Pitmanjaan yook’otoob

(is repeated)

Tumen tan u taloob u dzacoó u pothiloob

Jeé bix u bin y paxil

Bey u bin u yoó k’oitl

Tak tu taan lé xmamatziloboo

Ku yuchul lé xkakachmek’oob

koten a wileex

Tumen dzook u k’uchul

Tú, k’inil lé xpoostaniloó

lé xpostaniloó.

MAKE-UP

It’s time to put on makeup

and all the young

they dance very rowdy.

(is repeated)

They all come to have fun.

To the rhythm of the music they dance

and even in the presence of mothers

they embrace while dancing.

Everyone come see it.

because it has arrived

makeup time,

to put on makeup

3. JACH JADZUCHECH (pretty mestiza), country waltz in 3/4.

The waltz, a dance of Austro-Gemanic origin, was severely criticized at the beginning of the 19th century by the colonial authorities, considering it immoral. However, as a result of Independence, it became both the quintessential rhythm of the Mexican song and the obligatory dance of the bourgeoisie.

During the 19th century, magnificent examples of waltzes were composed, which reached their peak in the Porfirian era. Although it is already a modern dance, it continues to be performed in rural areas, preserving some of its ingenuity and the elegance of its melodic lines.

“JACH JADZUCHECH”

Bukaá jadzutzil

ken k’unchkech tií fiknal

Yeetel a chen t’uch

Yeetel a kichkelen boóch’.

Bukaá jadzutzil

ken chen jookech ok’ot

Yeetel u chen chakil

U chen booxil a chií.

Bukaá jadzutzil

A chen lolootka a fook

Yoók’ol u bak cheé

Chen jeetzekbalú jun.

Tak y pukcik’al

Ká betik u lenlenbal

Tumen jeetán maloobá

A fook’ot ch’upal.

Kaá pekcik yool y pukcik’al

Yeetel a kook’ot beyoó

Ken y filech ti fiknal

Kaá dzikten kiimak olal.

Leé beetik teech u yumil

Y yaakunal yeetel y kuxtal

Y foogel yaan a dzikteen

ti yump’el dzutz a pukcik’al.

PRETTY MIXED

How beautiful it is

when you come next to me,

with your chongo

and your precious rebozo.

How beautiful it is

when you go out dancing

with the crimson color

of your lips.

How beautiful it is

when you heel

and cross your feet

on the platform

To my heart

you make throb,

because you dance very well

girl.

You shake my heart

with your way of dancing

when i see you next to me

You give me a lot of joy.

Because you are the owner

of my life and my love,

I know that you will give me

in a single kiss the heart.

bomb

Kaach y yaakumaneché

U bak’e weech ki tasik tech

Belaá má y yaakumaneché

cheén u nej ki tich’iktech

Beyooo.

bomb

Before when I loved you

I brought you armadillo meat,

but now that I don’t love you anymore

I only bring you the bottom.

Sooo

4. THE LITTLE BUNNY, revelry 6/8.

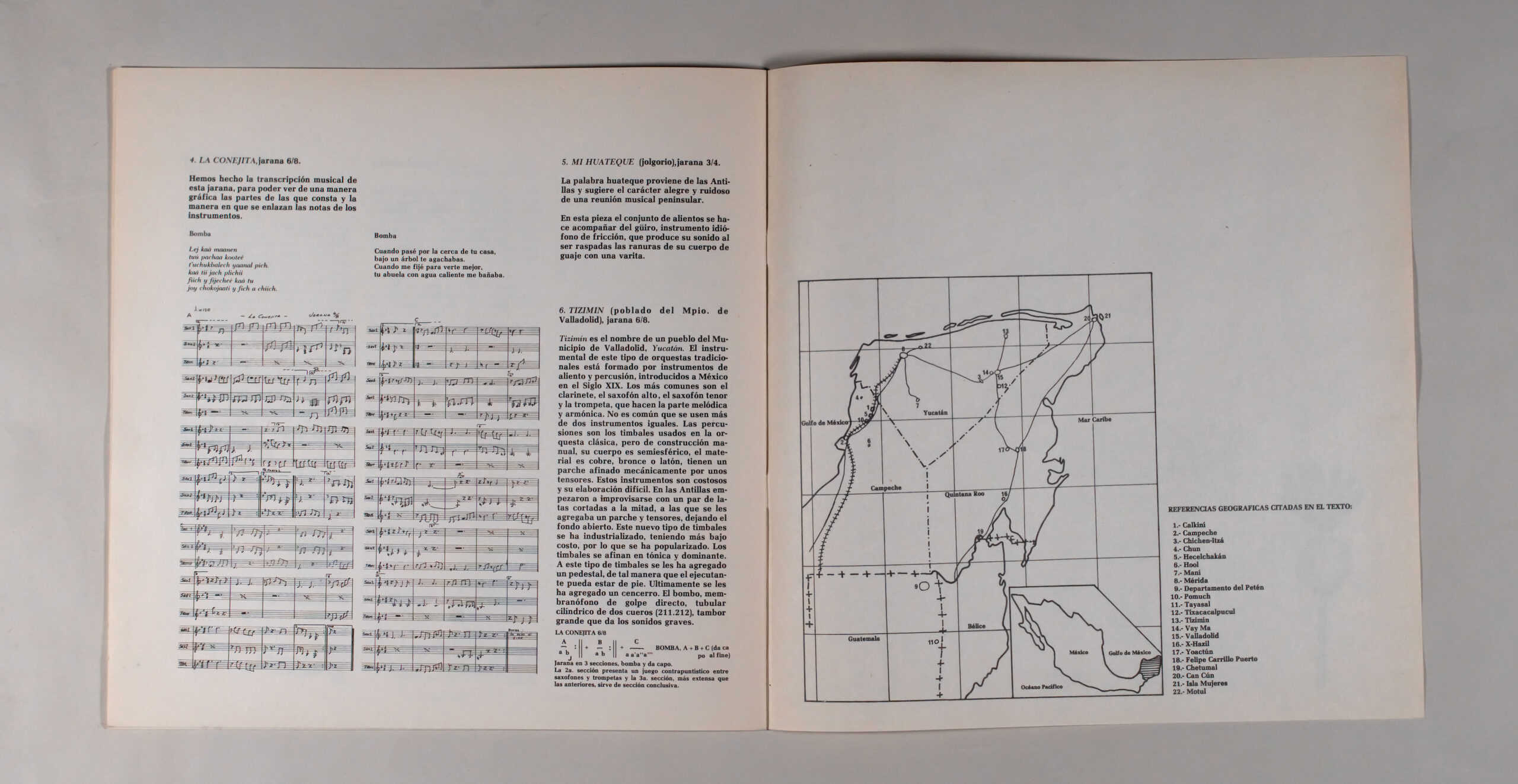

We have made the musical transcription of this jarana, to be able to see in a graphic way the parts of which it consists and the way in which the notes of the instruments are linked.

Bomb

Lej kaá maanen

tuú pachaa kooteé

t’uchukbalech yaanal pich.

kaá tii jach plichii

fiich y fijecheé kaá tu

joy chokojaati y fich a chich.

Bomb

When I passed by the fence of your house,

under a tree you crouched.

When I looked to see you better,

Your grandmother bathed me with hot water.

5. MY HUATEQUE (fun), revelry 3/4.

The word huateque comes from the Antilles and suggests the cheerful and noisy character of a peninsular musical gathering.

In this piece, the set of woodwinds is accompanied by the güiro, an idiophone friction instrument, which produces its sound by scraping the grooves in its gourd body with a wand.

6. TIZIMIN (town of the Municipality of Valladolid), revelry 6/8.

Tizimín is the name of a town in the Municipality of Valladolid, Yucatán. The instrumental of this type of traditional orchestras is made up of wind and percussion instruments, introduced to Mexico in the 19th century. The most common are the clarinet, the alto saxophone, the tenor saxophone and the trumpet, which make the melodic and harmonic part. It is not common for more than two identical instruments to be used. The percussions are the timpani used in the classical orchestra, but of manual construction, its body is hemispherical, the material is copper, bronze or brass, they have a patch mechanically tuned by tensioners. These instruments are expensive and difficult to make. In the Antilles they began to improvise with a couple of cans cut in half, to which they added a patch and turnbuckles, leaving the bottom open. This new type of timpani has been industrialized, having a lower cost, which is why it has become popular. The timpani are tuned in tonic and dominant. A pedestal has been added to this type of timpani, so that the performer can stand up. Lately a cowbell has been added to them. The bass drum, direct hit membranophone, cylindrical tubular with two skins (211.212), large drum that gives bass sounds.

THE LITTLE BUNNY 6/8

Jarana in 3 sections, bomba and da capo.

The 2nd section presents a contrapuntal game between saxophones and trumpets and the 3rd. This section, longer than the previous ones, serves as a concluding section.

GEOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES CITED IN THE TEXT:

1.- Calkiní

2.- Campeche

3.- Chichen-Itza

4.- Chun

5.- Hecelchakan

6.- Hool

7.- Peanut

8.- Merida

9.- Department of Petén

10.- Pomuch

11.- Tayasal

12.- Tixacacalpucul

13.- Tizimin

14 – Go Ma

15.- Valladolid

16. X-Hazil

17.- Yoactún

18.- Felipe Carrillo Puerto

19.- Chetumal

20.- Can Cun

21.- Isla Mujeres

22.- Motul

THE RESEARCH TASKS AND COLLECTION OF MATERIALS THAT MADE THE REALIZATION OF THIS ALBUM POSSIBLE WERE ACHIEVED THANKS TO MRS. CARMEN ROMANO DE LOPEZ PORTILLO, PRESIDENT OF THE NATIONAL FUND FOR SOCIAL ACTIVITIES (FONAPAS), FOR THE FINANCING GRANTED TO THE AUDIOVISUAL ETHNOGRAPHIC ARCHIVE OF THE NATIONAL INDIGENIST INSTITUTE WITHIN THE OLLIN YOLIZTLI PROGRAM.

THE EDITION OF THESE CULTURAL REVALUATION MATERIALS WAS ALSO COVERED WITH THE GENEROUS FINANCIAL CONTRIBUTION OF VARIOUS TRADE UNIONS.

ALFREDO ELIAS

DIRECTOR OF THE NATIONAL FUND FOR SOCIAL ACTIVITIES

IGNACIO OVALLE FERNANDEZ

GENERAL DIRECTOR OF THE NATIONAL INDIGENIST INSTITUTE

JUAN CARLOS COLIN

HEAD OF THE AUDIOVISUAL ETHNOGRAPHIC ARCHIVE OF THE NATIONAL INDIGENIST INSTITUTE

JOSE ANTONIO GUZMAN

HEAD OF THE ETHNOGRAPHY AND ETHNOMUSICOLOGY UNIT

ANGEL AGUSTÍN PIMENTEL, J. JESUS HERRERA PIMENTEL AND ALEJANDRO MENDEZ ROJAS

ETHNOMUSICOLOGY UNIT

RODOLFO SÁNCHEZ ALVARADO, FIELD RECORDING; ENRIQUE “HEINI” KUHLMANN, EDITION; CECILIA DURÁN AND JEANNE DURÁN, DESIGN; GERMAN HERRERA, PHOTOGRAPHS; JOSÉ MANUEL PAINTED, WRITING AND STYLE.

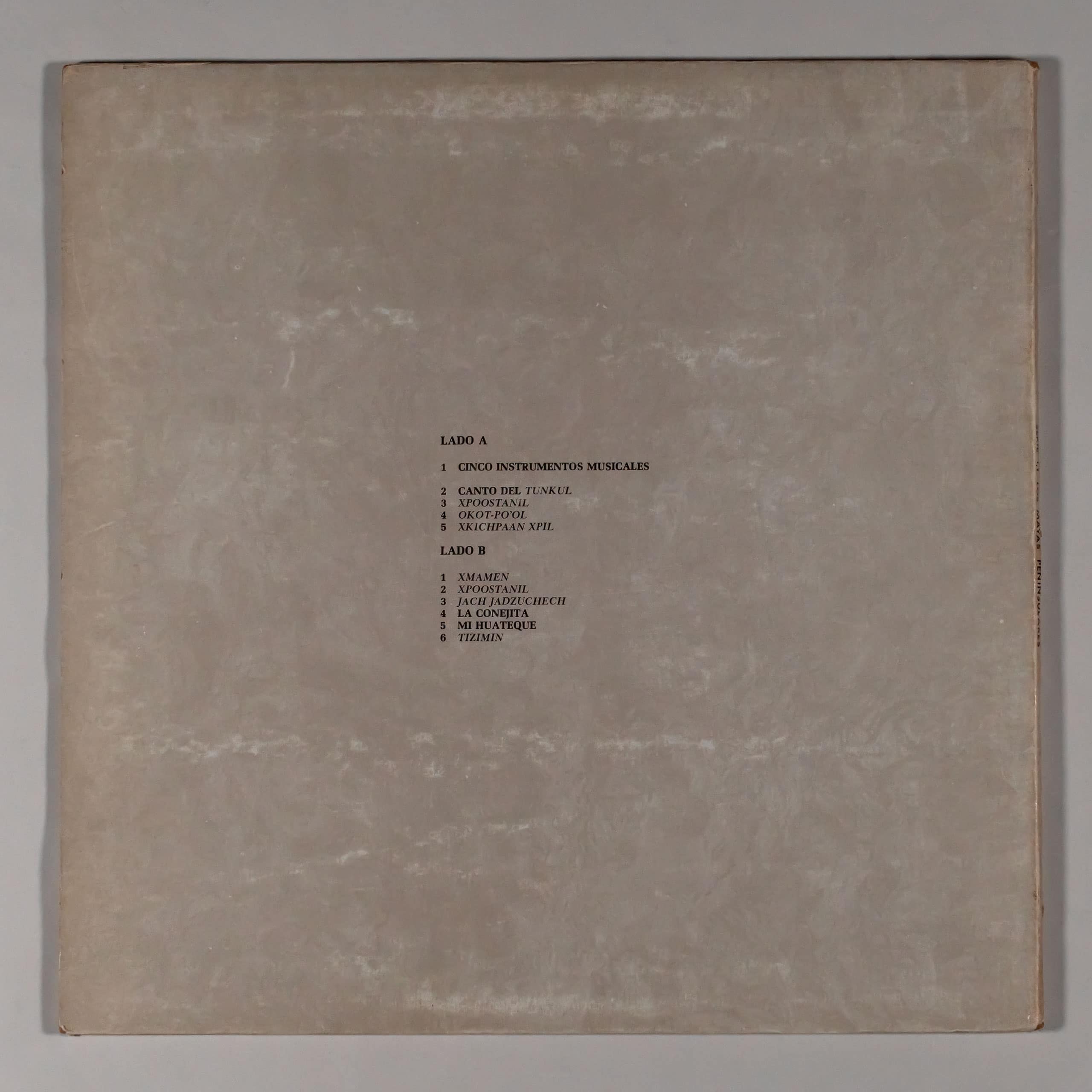

PROGRAM

SIDE 1

A1 FIVE PREHISPANIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS 3:05

Performer(s): CHULBIÍ-JUÚB – Snail trumpet; TUN-KUL – Wooden drum; SOOT or XCHIILCOOB – Rattles; BOXEL or PACH-AAC – Turtle shell; XOXOBO or TABZE – Clay whistle.

Recorded in the XV meeting in Calkiní, Campeche, on the 1st. December 1978.

A2 SONG OF THE TUN-KUL, Ceremonial Song 4:23

Performer(s): POMUCH GROUP. Instruments: Voices and Tunk-Kul.

Recorded in the XV meeting in Calkiní, Campeche, on the 1st. December 1978.

A3 XPOOSTANIL (Makeup), revelry ¾ 2:34

Performer(s): A MEMBER OF THE CHUN GROUP. Instruments: Harmonica and Singing.

Recorded in the XV meeting in Calkini, Campeche, on the 1st. December 1978.

A4 OKOT-PO’OL (Head Dance), dance 4/4 2:50

Performer(s): MAYAPASH FROM YOACTUN, CARRILLO PUERTO. Instruments: 2 Violins, Tarola, Bass Drum.

Recorded at the XXIX meeting in X-Hazil Sur, Felipe Carrillo Puerto, Quintana Roo, on March 15, 1980.

A5 XKICHPAAN XPIL (Beautiful pillar), Waltz ¾ 3:08

Performer(s): DZINUP GROUP, VALLADOLID, YUC. Instruments: Bombolito, Rope, 4 Guitars, Güiro, Harmonica.

Recorded at the XXIX meeting in X-Hazil Sur, Felipe Carrillo Puerto, Quintana Roo, on March 15, 1980.

SIDE 2

B1 XMAMEN (lady), Rumba 6/8 3:05

Performer(s):

B2 XPOOSTANIL (Make-up), Jarana 3/4 1:50

Performer(s):

B3 JACHJADZUCHECH (Mestiza Bonita), Country Waltz ¾ 2:20

Performer(s): CALKINÍ GROUP, MADE UP OF: TOMAS DZIB DZIB, JAIME EK-NAAL, ROLANDO EK-NAAL AND ADRIANO EK-NAAL. Instruments: 2 sixth guitars, tercerola guitar and Marimbol.

Recorded in the XV meeting of Calkini, Campeche, the 1st. December 1978. Rerecorded on Thursday, April 3, 1980 in Mexico, D.F.

B4 THE LITTLE BUNNY, Jarana 6/8 3:38

Performer(s): TIXACACALPUCUL GROUP. Instruments: Clarinet, Trumpet, 2 Saxophones, Timbales.

Recorded at the VIII meeting in Valladolid, Yucatán, on June 24, 1978.

B5 MI HUATEQUE (Dance, Jolgorio, Meeting), jarana ¾ 2:37

Author: Isidro May

Performer(s): UAY MA GROUP DIRECTED BY MASTER ABUNDIO TAC. Instruments: Clarinet, Trumpet, 2 Saxophones, Timbales, Güiro.

Recorded at the VIII meeting in Valladolid, Yucatán, on June 24, 1978.

B6 TIZIMÍN (Town of the Municipality of Valladolid), Jarana 6/8 3:27

Performer(s): GROUP FROM VALLADOLID, YUCATÁN, DIRECTED BY MASTER HÉCTOR CASTILLO NIETO. Instruments: Clarinet, 2 Trumpets, 2 Saxophones, Timbales.

Recorded at the VIII meeting in Valladolid, Yucatán, on June 24, 1978.

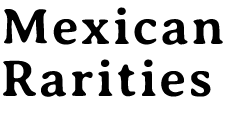

SIDE A

1 FIVE MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS

2 SONG OF THE TUNKUL

3XPOOSTANIL

4 OKOT-PO’OL

5 XKICHPAAN XPIL

SIDE B

1 X MOM

2 XPOOSTANIL

3 JACH JADZUCHECH

4 THE BUNNY

5 MY HUATEQUE

6 TIZIMIN

Tracklist:

THE PENINSULAR MAYAS

SIDE 1

- A1 FIVE PREHISPANIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS 3:05

Performer(s): CHULBIÍ-JUÚB – Snail trumpet; TUN-KUL – Wooden drum; SOOT or XCHIILCOOB – Rattles; BOXEL or PACH-AAC – Turtle shell; XOXOBO or TABZE – Clay whistle. - A2 SONG OF THE TUN-KUL, Ceremonial Song 4:23

Performer(s): POMUCH GROUP. Instruments: Voices and Tunk-Kul. - A3 XPOOSTANIL (Makeup), revelry ¾ 2:34

Performer(s): A MEMBER OF THE CHUN GROUP. Instruments: Harmonica and Singing. - A4 OKOT-PO’OL (Head Dance), dance 4/4 2:50

Performer(s): MAYAPASH FROM YOACTUN, CARRILLO PUERTO. Instruments: 2 Violins, Tarola, Bass Drum. - A5 XKICHPAAN XPIL (Beautiful pillar), Waltz ¾ 3:08

Performer(s): DZINUP GROUP, VALLADOLID, YUC. Instruments: Bombolito, Rope, 4 Guitars, Güiro, Harmonica.

SIDE 2

- B1 XMAMEN (lady), Rumba 6/8 3:05

Performer(s): - B2 XPOOSTANIL (Make-up), Jarana 3/4 1:50

Performer(s): - B3 JACHJADZUCHECH (Mestiza Bonita), Country Waltz ¾ 2:20

Performer(s): CALKINÍ GROUP, MADE UP OF: TOMAS DZIB DZIB, JAIME EK-NAAL, ROLANDO EK-NAAL AND ADRIANO EK-NAAL. Instruments: 2 sixth guitars, tercerola guitar and Marimbol. - B4 THE LITTLE BUNNY, Jarana 6/8 3:38

Performer(s): TIXACACALPUCUL GROUP. Instruments: Clarinet, Trumpet, 2 Saxophones, Timbales. - B5 MI HUATEQUE (Dance, Jolgorio, Meeting), jarana ¾ 2:37

Author: Isidro May

Performer(s): UAY MA GROUP DIRECTED BY MASTER ABUNDIO TAC. Instruments: Clarinet, Trumpet, 2 Saxophones, Timbales, Güiro. - B6 TIZIMÍN (Town of the Municipality of Valladolid), Jarana 6/8 3:27

Performer(s): GROUP FROM VALLADOLID, YUCATÁN, DIRECTED BY MASTER HÉCTOR CASTILLO NIETO. Instruments: Clarinet, 2 Trumpets, 2 Saxophones, Timbales.

Credits:

THE RESEARCH TASKS AND COLLECTION OF MATERIALS THAT MADE THE REALIZATION OF THIS ALBUM POSSIBLE WERE ACHIEVED THANKS TO MRS. CARMEN ROMANO DE LOPEZ PORTILLO, PRESIDENT OF THE NATIONAL FUND FOR SOCIAL ACTIVITIES (FONAPAS), FOR THE FINANCING GRANTED TO THE AUDIOVISUAL ETHNOGRAPHIC ARCHIVE OF THE NATIONAL INDIGENIST INSTITUTE WITHIN THE OLLIN YOLIZTLI PROGRAM.

THE EDITION OF THESE CULTURAL REVALUATION MATERIALS WAS ALSO COVERED WITH THE GENEROUS FINANCIAL CONTRIBUTION OF VARIOUS TRADE UNIONS.

ALFRED ELIAS

DIRECTOR OF THE NATIONAL FUND FOR SOCIAL ACTIVITIES

IGNACIO OVALLE FERNANDEZ

GENERAL DIRECTOR OF THE NATIONAL INDIGENIST INSTITUTE

JUAN CARLOS COLIN

HEAD OF THE AUDIOVISUAL ETHNOGRAPHIC ARCHIVE OF THE NATIONAL INDIGENIST INSTITUTE

JOSE ANTONIO GUZMAN

HEAD OF THE ETHNOGRAPHY AND ETHNOMUSICOLOGY UNIT

ANGEL AGUSTÍN PIMENTEL, J. JESUS HERRERA PIMENTEL AND ALEJANDRO MENDEZ ROJAS

ETHNOMUSICOLOGY UNIT

RODOLFO SÁNCHEZ ALVARADO, FIELD RECORDING; ENRIQUE “HEINI” KUHLMANN, EDITION; CECILIA DURÁN AND JEANNE DURÁN, DESIGN; GERMAN HERRERA, PHOTOGRAPHS; JOSÉ MANUEL PAINTED, WRITING AND STYLE.