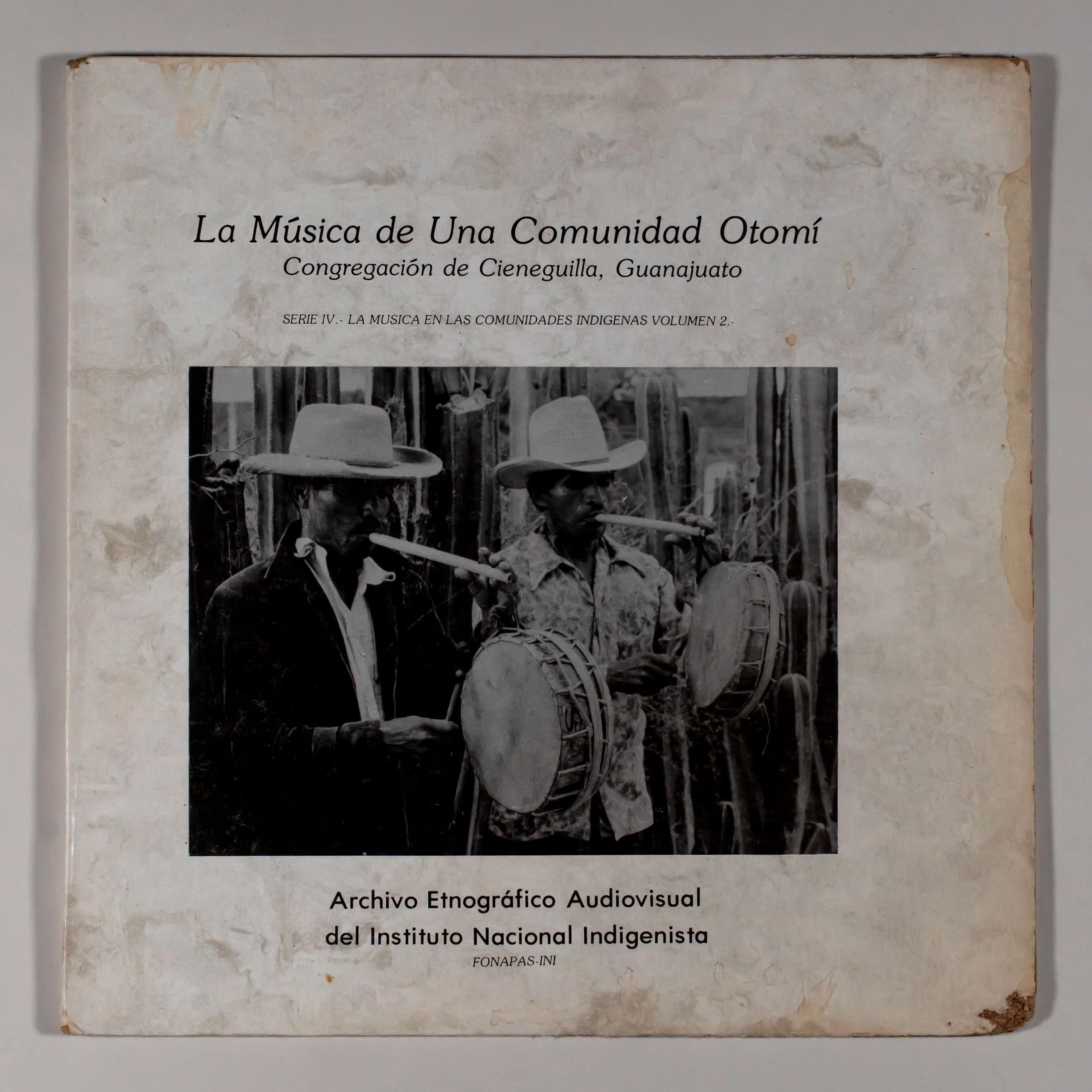

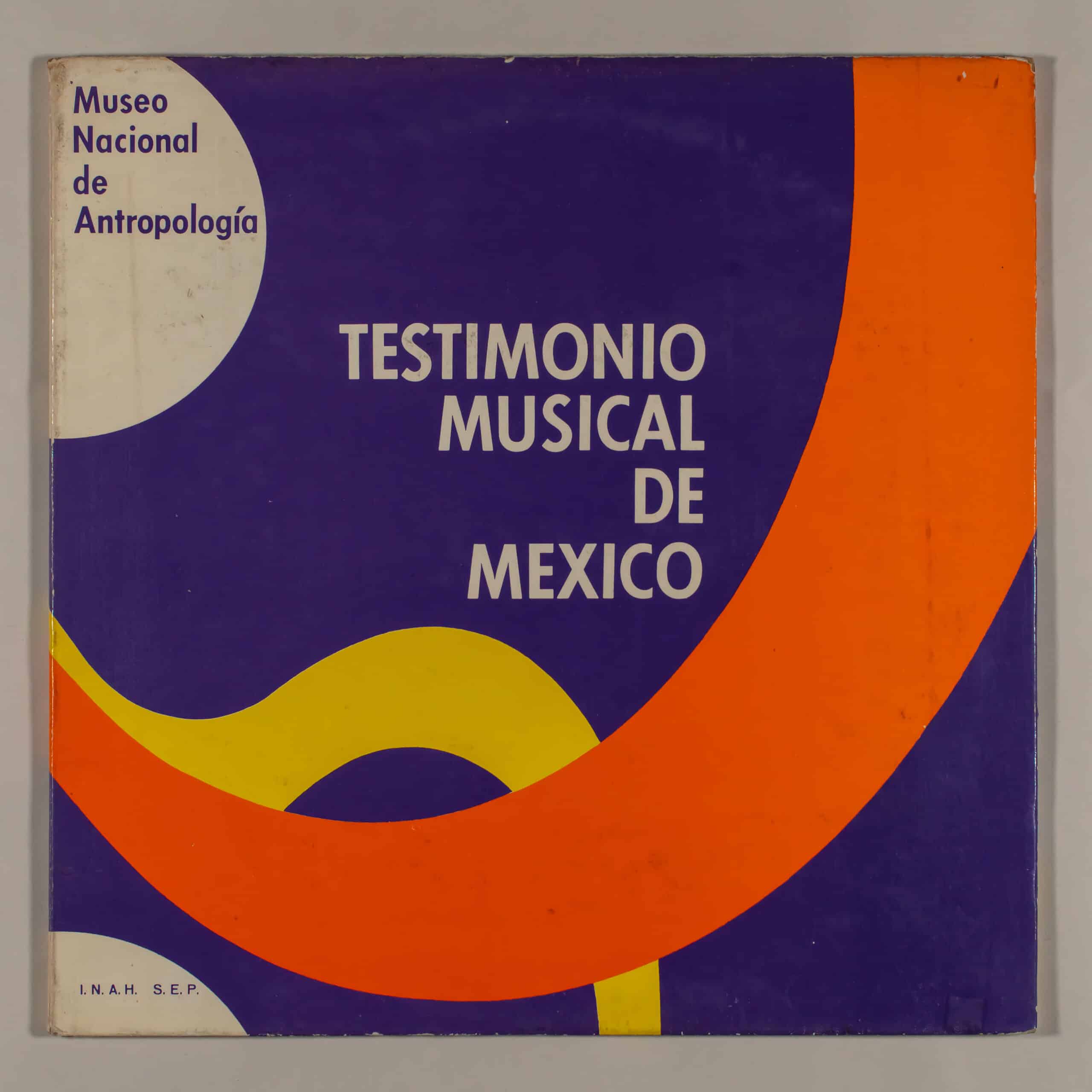

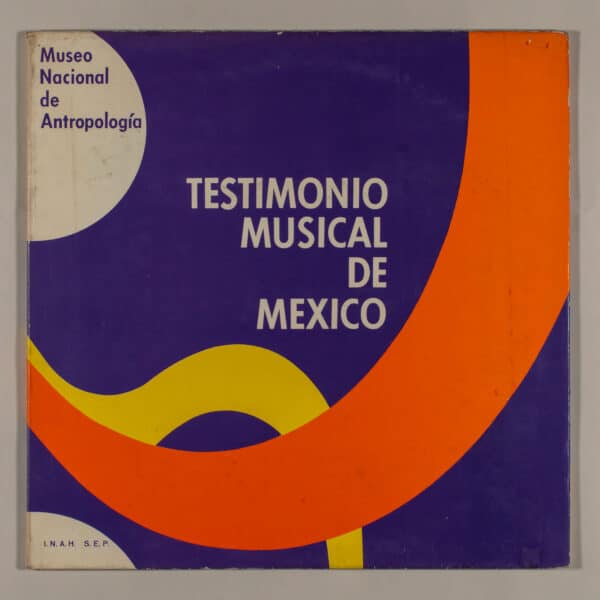

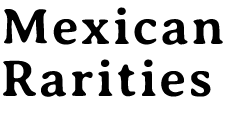

MUSICAL TESTIMONY OF MEXICO

INAH SEP

|

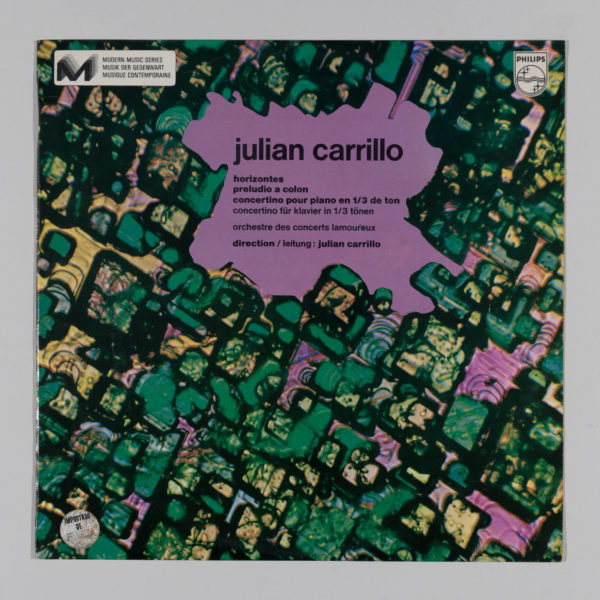

Label: INAH-SEP MNA-01 Released: 1964 |

Country: Mexico |

Info:

ANTHROPOLOGY NATIONAL MUSEUM

MUSICAL TESTIMONIAL of MEXICO MUSICAL TESTIMONIAL OF MEXICO

INAH-SEP

The album consists of two parts: one dedicated to the traditional music of contemporary indigenous cultures and the other to the heritage of mestizo musicians. Between both traditions there is no clear difference, since, in reality, they are interrelated.

However, it can be said that indigenous music is more conservative. The relative isolation in which these groups have remained by will or by force determines that elements of ancient origin are preserved in their traditions. These can go back in some cases to pre-Hispanic times, although the most frequent and dominant are of colonial origin and European affiliation. There are also more recent and still contemporary elements.

Much of the repertoire of indigenous groups has an obvious social purpose that is performed in religious festivities and although a good part of the music is frankly profane, it is practiced associated with the festivities of the ritual calendar, around which almost all of the music revolves. the life of the indigenous community. This religiosity, although definitively and profoundly Catholic, is far from orthodoxy and is a frankly popular phenomenon.

To a lesser degree, indigenous cultures practice personal music: songs of love, sadness or mockery. Rarely, on the other hand, is the presence of secular festive genres recorded, such as couple dances.

Economically, indigenous musicians and dancers are rarely professionals; perhaps at parties they receive some additional income, although more often than not they will be invited to those who are entertained with food and drink. Instead, they will always gain prestige, fame and respect -status- within their group, and will be able to climb the social ladder through their performance as musicians. Hence, in terms of quality, the indigenous musician is eminently professional.

Mestizo music is formally less conservative. Many of its genres begin their evolution from Spanish models in the last years of the colonial period and are set towards the middle of the 18th century or even later. As a consequence of the closer contact of the mestizo group with urban society, its repertoire is subject to a more rapid evolution than the indigenous heritage.

Ultimately, mestizo music is an integral part of that complex poorly defined as national culture.

In mestizo music, a profane character prevails. The music incorporated into religious ceremonies does not represent, as in indigenous cultures, the foundation of the repertoire. On the contrary, the festive, epic and lyrical genres are the best exponents of this traditional heritage. Their social function is less obvious, as there are few institutionalized pretexts for the practice of most genres, which are used on a variety of occasions. But in general terms this social function is similar to that of indigenous cultures.

In the mestizo group, economic professionalism is more widespread, and the number of musicians who play it full time is considerable. There is also the musician by vocation, who preserves an enormous wealth of popular heritage that has escaped registration, and whose rescue is as urgent as it is necessary.

Between these two ideal types —indigenous and mestizo music— the examples that we offer in this disc are located.

NOTE:

All the examples included were recorded in their places of origin and in the conditions in which they are usually practiced. This material was previously published by the Seminary of Anthropological Studies for the course on the folklore of Mexico, in the year 1963.

Recordings made by:

Tomás Stanford, I.N.A.H.:

Face A: examples 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 9;

Face B: examples 2, 3, 4 and 6.

Irene y Arturo Warman: Face A: examples 2, 7 and 8;

Face B: examples 1 and 5.

Notas de Arturo Warman.

Rights reserved by the National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico, 1967.

Distribution: Educational Services Section

Anthropology National Museum

De la Milla street,

Chapultepec Forest,

Mexico, D. F.

Face: A

indigenous music

1.—MUSIC OF THE SAINTS. Venustiano Carranza, Chiapas

On the occasion of the great religious festivities of this town in the highlands of Chiapas, an instrumental group is installed in the atrium of the church that through this music pays homage to the Saints, at the same time that it announces the celebration and the continuity of the tradition. It is played by a reed flute with three holes —pito chiquito— which alternates with three bugles of different tonality; the rhythmic accompaniment is performed by two drums of different sizes. It consists of eight sections or movements, of which only the first is included.

Performers: Cornets: Manuel Velasco and Domingo Gómez; flute: José de la Torre; big drum: Manuel Hidalgo Vázquez; small drummer: Manuel Calvo.

2.—BIG DANCE. Tampate, San Luis Potosí

It derives its name —pulitson in Huaxteco— from the instrument with which it is played: a harp with 31 strings, which is called large to differentiate it from another with only 29. Usually, it is accompanied by a small two-stringed violin or rabelito that develops the rhythm and that in this recording is absent. These instruments are of European origin and are believed to have been introduced no later than the 17th century. This dance also has a religious purpose and is danced in honor of the Saints during the whole night of the eve of the festivity. It has more than 100 different sounds identified with a name, almost always that of an animal. The included son is called “the hive fly” (bee).

Performers: Francisco Guzmán.

3.—DEER DANCE. La Playa, El Naranjo, Sinaloa

Also with a religious purpose, this dance of the Mayo group is danced in honor of the Saints of the Catholic pantheon. There is a flute and a patch drum, a water drum and scrapers to which are added rattles, bells and strings of seeds tied to the dancers’ ankles. This dance, that of the deer itself, invariably alternates with that of the pascolas, which is accompanied by harp and violin, to form, in fact, a single choreographic unit. Some instruments of this dance, such as the water drum and the scrapers, seem to have a pre-Hispanic origin, while the others originate in Europe; for what constitutes a good example of musical syncretism.

4.—DANCE OF THE BULLS. San Pedro Atoyac, Oaxaca

The dances of this region are in charge of a society formed expressly for that purpose. It is called “los tejorones” and takes its name from a character —the tejoronero— from the tiger dance. The character of the character gives the dances a satirical and mocking intention towards the mestizos. Despite this, it is incorporated into the great festivities of San Pedro and San Nicolás.

Performers: Reed flute: Ángel Jiménez; Drum: Toribio Vázquez.

5.—HUECANIAS. Xoxocotla, Morelos

Song of a profane nature and lyrical intention, a genre that has been widely developed among the Nahuatl-speaking population of the State of Morelos. Due to its musical structure, this genre reveals reminiscences of the “syrup” of the last century. The example included is a love song, in a bilingual Nahuatl-Spanish version, performed by a 12-year-old girl.

Performers: Zenaida Vargas.

6.—HOLY WEEK MUSIC. San Juan Bautista, Tuxpan, Jalisco

It serves to announce the feast of the Church, the Greater Week of the Catholic calendar. The use of the shawm, an instrument of European origin spread in the areas of Mexican or Nahuatl influence such as Tuxpan, recalls the intemperate bugle with which the representation of the Calvary and death of Jesus Christ was announced in Europe. The rhythmic accompaniment is in charge of a drum.

Performers: Shawm: Cesáreo Guzmán; Drum: Carmelo Ruiz Martinez.

7.—TIGRILLO DANCE. Mata del Tigre, Tantoyuca, Veracruz

Mimic dance in which a couple of dancers covered with the skin of an tigrillo, and with rattles and bells, imitate movements and attitudes of this animal. It is performed with a teponastle —a horizontal wooden drum of pre-Hispanic origin— and a reed flute with a turkey feather mouthpiece. It once had a magical content; then it was incorporated into the religious festive tradition of Catholic content, from which it was banished because the clergy considered it profane.

Performers: Teponastle: Juan Santiago; flute: Cristobal Santiago.

8.—LOVE SONG. San Pedro, Nayarit

The Huichol group has one of the widest repertoires of personal music, especially with romantic intentions. The musical accompaniment is performed with a violin and a tiny regionally made guitar. The training and musical capacity of this group is to such a remarkable degree that the members take turns indistinctly handling the instruments and singing; so in this case it was not possible to identify the interpreters.

9.—MUSIC OF SAINT LUCIA. Tenejapa, Chiapas

It is performed at the titular festival of Santa Lucia, patron saint of Tenejapa, a Tzeltal town in the highlands of Chiapas. This example is remarkable for its musical characteristics, above all a constant rhythmic evolution is masterfully achieved. And the lack of a regular compass; this scheme makes melodic resolution more difficult, and yet it is masterfully achieved.

Performers: Reed flute: Alonso Guzmán Xitan; drummer: Pedro López Tza’atzi; Cornet: Alonso López Fuí.

FACE: B

mestizo music

1.—QUETZA, DANCE SONGS. Distrito Federal

This piece is part of the musical and choreographic tradition of the group called the conquest dancers or concheros; this last name derives from the main instrument they use: a 10-string guitar with an armadillo or shell shell, as a sounding board, to which are added mandolins, huehuetl and teponastle —percussions copied from pre-Hispanic models— and strings of tied seeds at the feet of the dancers. Due to their purpose, festive dates and organization, these groups can be assimilated to the religious tradition of the type of indigenous dances; while due to the origin and character of its members they are located in the mestizo group and even urban in this case. The name of the dance is an apocope of Quetzalcóatl, a pre-Hispanic deity, although it can be assumed to have been adopted very recently.

Performers: Mandolins: Ernesto Ortiz and Pedro Matús; shells and dance: Andrés Segura, Dolores Ortiz, Belén Rodríguez and Guadalupe.

2.—THE HUEHUETECO, CHILEAN. Huehuetan, Guerrero

The Chilean is a secular and festive genre derived from the Chilean cueca; This was introduced during the “gold rush”, in the last century, by South American sailors and miners who arrived in Acapulco on their way to northern California. Once adopted, this form has evolved into its contemporary style, in which one or more sixth guitars are used to accompany improvised verses. The included example is characteristic of an old fashion in interpretation.

3.—COMITÁN DE LAS FLORES, CANCIÓN. Comitán, Chiapas

Este ejemplo, de intención lírica y profana, pese a ser moderno, tiene la estructura de la chacona del siglo XVII. Se interpreta con una mandolina y una guitarra séptima de 14 cuerdas, instrumentos muy usuales hace unos 25 años en la ciudad que da el nombre a esta canción.

Intérpretes: Guitarra y canto: Horacio Monjarrez; mandolina, Antonio Monjarrez.

4.—CORNELIO VEGA, CORRIDO. Estación Vicam, Sonora

This example is a classic of the most widespread epic narrative genre in the country, which achieved its splendor in the last decade of the previous century. The corrido is undoubtedly a derivative of Spanish romance, although it has reached full originality in Mexico, where it was widely used as a vehicle for disseminating news and even myths of popular taste. The performers in this example are descended from a Yaqui family.

Performers: Guitars and voices: Molina Brothers.

5.—SAN LORENZO, HUASTECO SON. Ciudad Valles, San Luis Potosí

The son is a generic name that is applied to many regional varieties of festive music danced by couples that frequently use the zapateado, the Huasteca variety has reached remarkable development. It integrates true virtuosity in handling instruments within a complex musical structure; attached to the above is the song, often picaresque in intention, which is intoned using the short falsetto as adornment of the melody.

Performers: Ensemble “Alma de las Tres Huastecas”; violin: Dionisio Ramos; fifth or huapanguera guitar: José Navarro; jarana: Crescencio Martinez.

6.—THE HAPPY LITTLE MORNING, TIERRA CALIENTE SON. Apatzingán, Michoacán

This example is another variety of son, developed on the coast and warm lands of the State of Michoacán. Like our previous example, it is a musical form that has maintained a constant evolution for almost two centuries. This variant is interpreted by the “big harp ensemble” in which, in addition to the instrument that gives it its name, violins and jaranas take part.

Performers: Ensemble “Los Cardenales”.

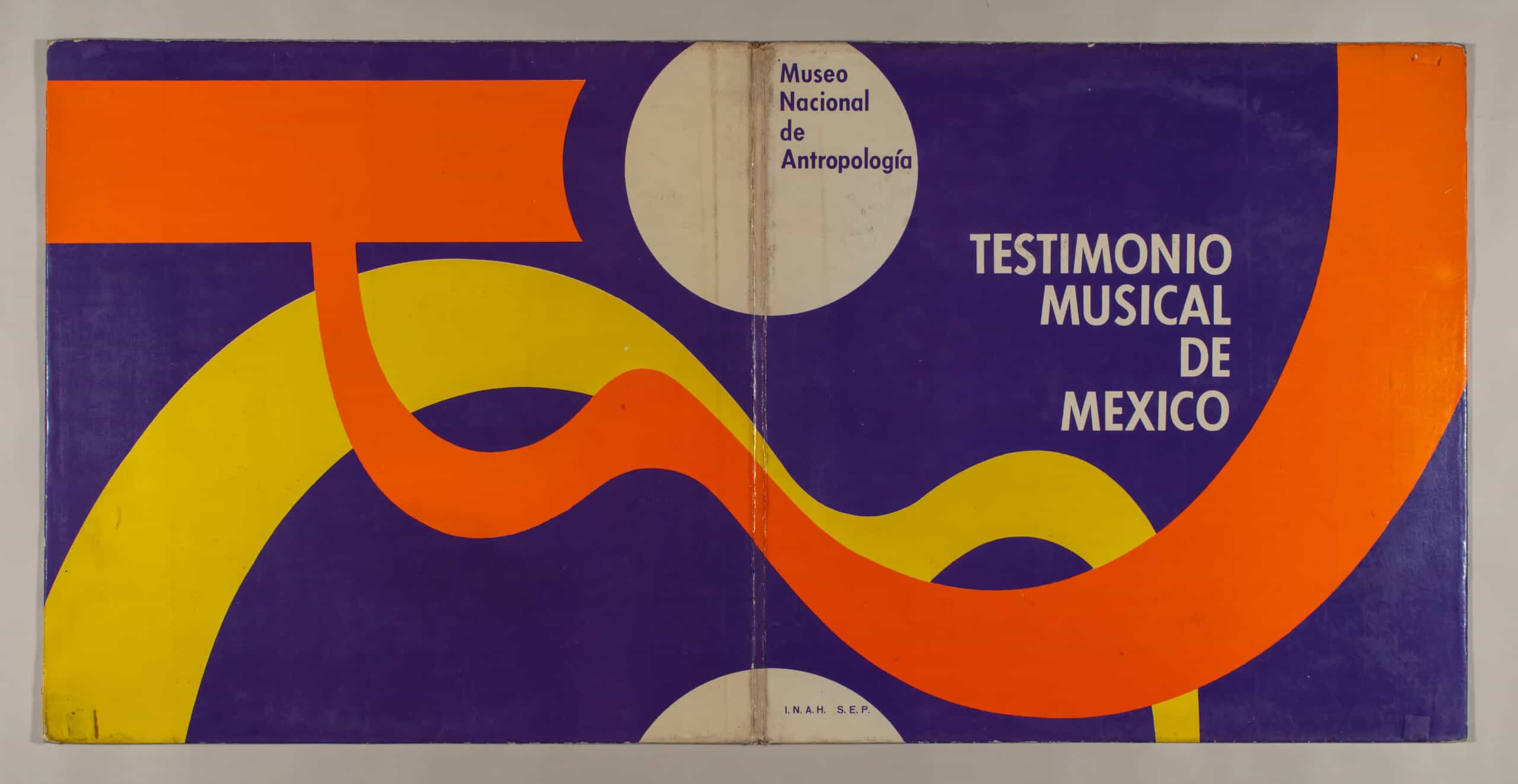

Tracklist:

MUSICAL TESTIMONY OF MEXICO

SIDE 1

INDIGENOUS MUSIC

- A1 Music Of The Saints.– Venustiano Carranza, Chiapas

Performers: Cornets: Manuel Velasco and Domingo Gómez; flute: José de la Torre; big drum: Manuel Hidalgo Vázquez; small drummer: Manuel Calvo. - A2 Big Dance.– Tampate, San Luis Potosí

Performer: Francisco Guzmán. - A3 Deer Dance.– The Beach, El Naranjo, Sinaloa

- A4 Dance Of The Bulls.– San Pedro Atoyac, Oaxaca

Performers: Reed flute: Ángel Jiménez; Drum: Toribio Vázquez. - A5 Huecanias (Song).– Xoxotla, Morelos

Performers: Zenaida Vargas. - A6 Music Of Holy Week.– San Juan Bautista, Tuxpan, Jalisco

Performers: Shawm: Cesáreo Guzmán; Drum: Carmelo Ruiz Martinez. - A7 Tigrillo Dance.– Tantoyuca, Veracruz

Performers: Teponastle: Juan Santiago; flute: Cristobal Santiago. - A8 Love Song.– San Pedro, Nayarit

- A9 Music of Santa Lucia.– Tenejapa, Chiapas

Performers: Reed flute: Alonso Guzmán Xitan; drummer: Pedro López Tza’atzi; Cornet: Alonso López Fuí.

SIDE 2

MESTIZO MUSIC

- B1 Quetza (Dance Son).– Distrito Federal

Performers: Mandolins: Ernesto Ortiz and Pedro Matús; shells and dance: Andrés Segura, Dolores Ortiz, Belén Rodríguez and Guadalupe. - B2 The Huehueteco (Chilean).– Huehuetán, Guerrero

- B3 Comitan De Las Flores (Song).– Comitan, Chiapas

Performers: Guitar and singing: Horacio Monjarrez; mandolin, Antonio Monjarrez. - B4 Cornelio Vega (Corrido).– Vicam Station, Sonora

Performers: Guitars and voices: Hermanos Molina. - B5 The San Lorenzo (Huasteco son).– Ciudad Valles, San Luis PotosÍ

Performers: Ensemble “Alma de las Tres Huastecas”; violin: Dionisio Ramos; fifth or huapanguera guitar: José Navarro; jarana: Crescencio Martinez. - B6 La Mananita Alegre (Son From Tierra Caliente).– Apatzingan, Michoacán

Performers: Ensemble “Los Cardenales”.

Credits:

Field recordings by Tomás Stanford and Irene and Arturo Warman

Notes by Arthur Warman

Cover design by Constantino Lameiras

Mexico, 1967

Secretary of Public Education, Mr. Agustín Yáñez

Undersecretary for Cultural Affairs, Mr. Mauricio Magdaleno

Director of the National Institute of Anthropology and History, Doctor Eusebio Dávalos Hurtado

Director of the National Museum of Anthropology, Doctor Ignacio Bernal

Educational Services Section, Professor Ma. Cristina S. de Bonfil.

Field recordings by Tomás Stanford and Irene and Arturo Warman

Arturo Warman’s notes

Design of the cover by Constantino Lameiras

Mexico, 1967

Secretary of Public Education, Mr. Agustín Yáñez

Undersecretary for Cultural Affairs, Mr. Mauricio Magdaleno

Director of the National Institute of Anthropology and History, Doctor Eusebio Dávalos Hurtado

Director of the National Museum of Anthropology, Doctor Ignacio Bernal

Educational Services Section, Professor Ma. Cristina S. de Bonfil.

Thomas Stanford: Engraver

Irene Vázquez Vale: Engraver

Arturo Warman: Engraver, Associate Material Writer

Victor Acevedo Martinez: Editor

Martin Audelo Chicharo: Editor

Guadalupe Loyola Zarate: Editor

Benjamin Muratalla: Editor, Director

Irene Vazquez Valle: Editor

H. Alejandro Castellanos Garrido: Editor, Researcher

Gabriela Gonzalez Sanchez: Editor

Jasmine Rangel Evaristo: Editor

Grandma Records

Alfredo Huertero Casarrubias: Illustrator

Guillermo Santana Ramírez: Designer

Manuel Velasco: Musician

Domingo Gomez: Musician

Jose De la Torre: Musician

Manuel Hidalgo: Musician

Manuel Calvo: Musician

Francisco Guzman: Musician

Angel Jimenez: Musician

Toribio Vazquez: Musician

Cesareo Guzman: Musician

Carmelo Ruiz Martinez: Musician

Juan Santiago: Musician

Christopher Santiago: Musician

Alonso Guzman Xitan: Musician

Pedro López Tza´atzi: Musician

Alonso López I was: Musician

Ignacio Magallón: Musician, Singer

Moises Vargas: Musician

Juvencio Vargas: Musician

Mariachi Anguiano: Musician

Horacio Monjarrez: Musician, Singer

Antonio Monjarrez: Musician

Molina Brothers: Musician

Soul of the Three Huastecas Set: Musician

Large Harp Ensemble The Cardinals: Musician

Zenaida Vargas: Singer

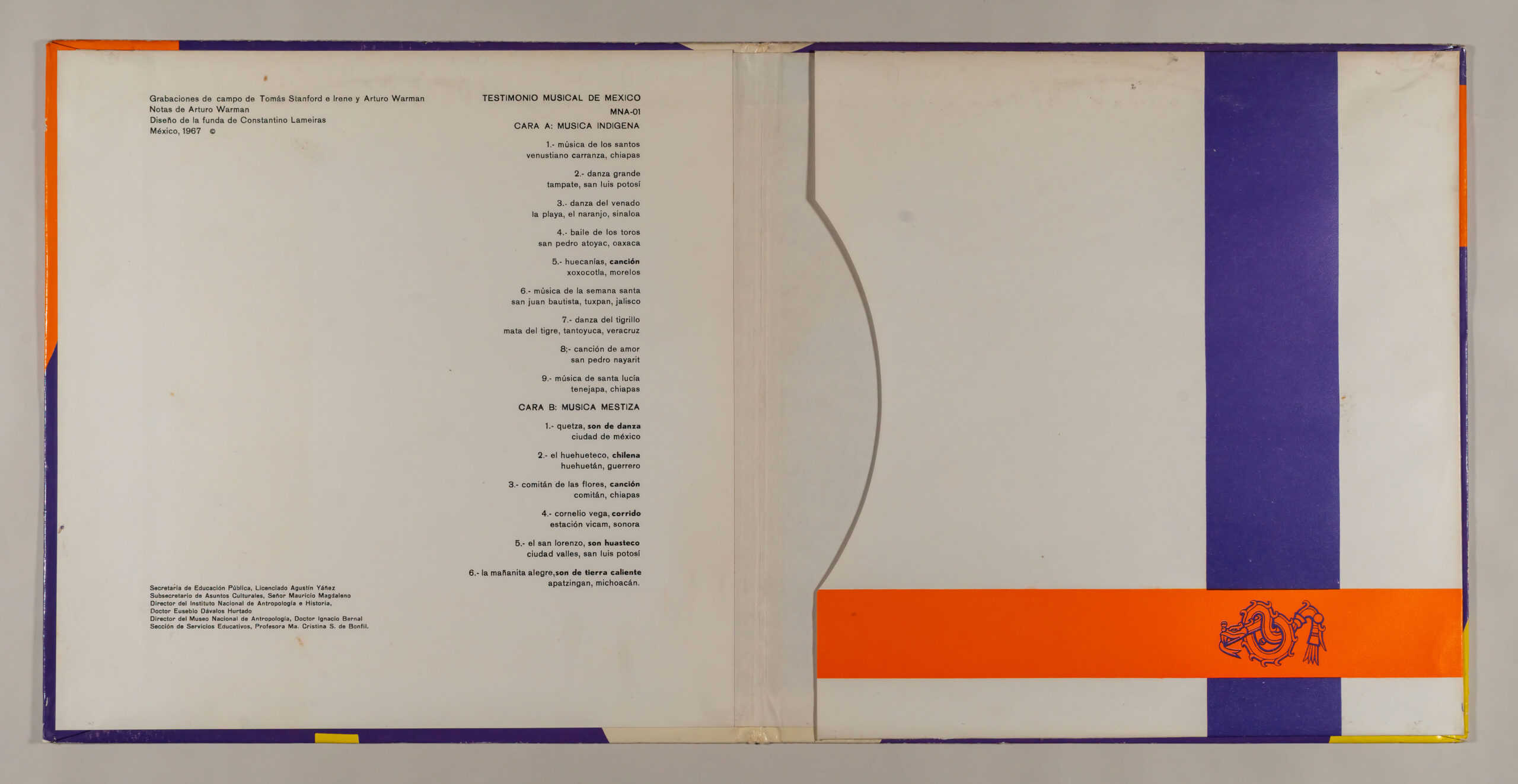

TESTIMONIO MUSICAL DE MEXICO Musica Indigena LP INAH SEP 1967 Museo Antropologia

TESTIMONIO MUSICAL DE MEXICO Musica Indigena LP INAH SEP 1967 Museo Antropologia