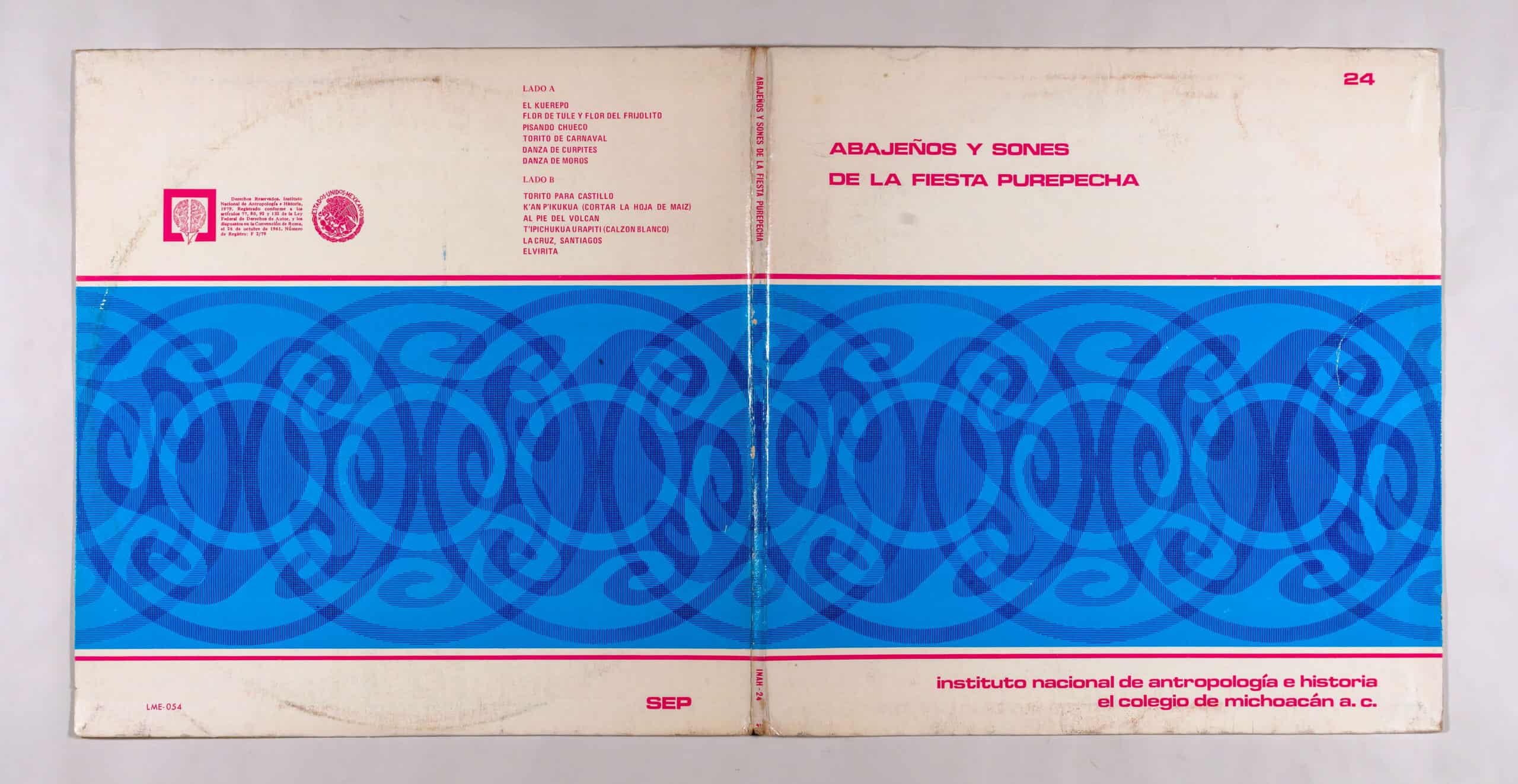

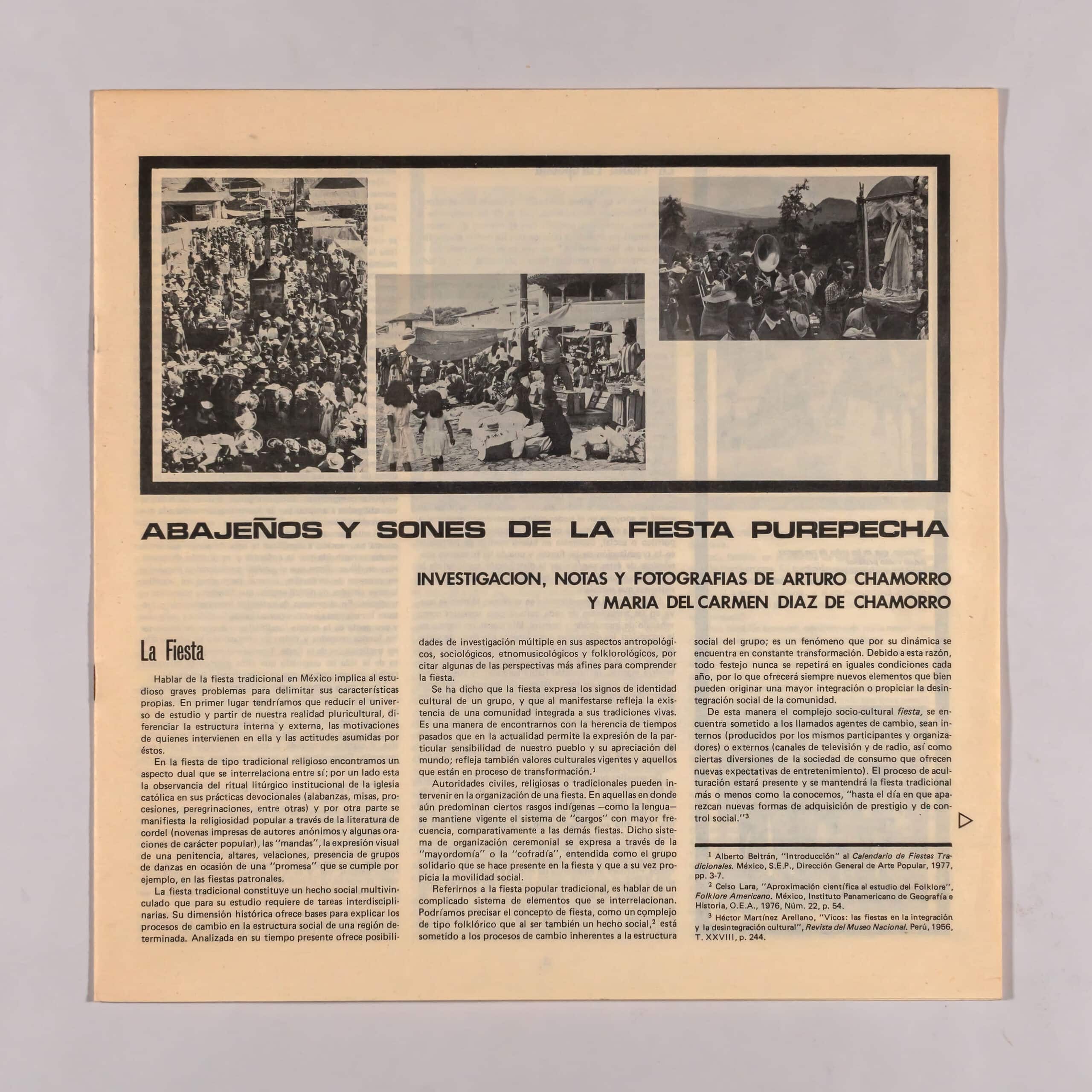

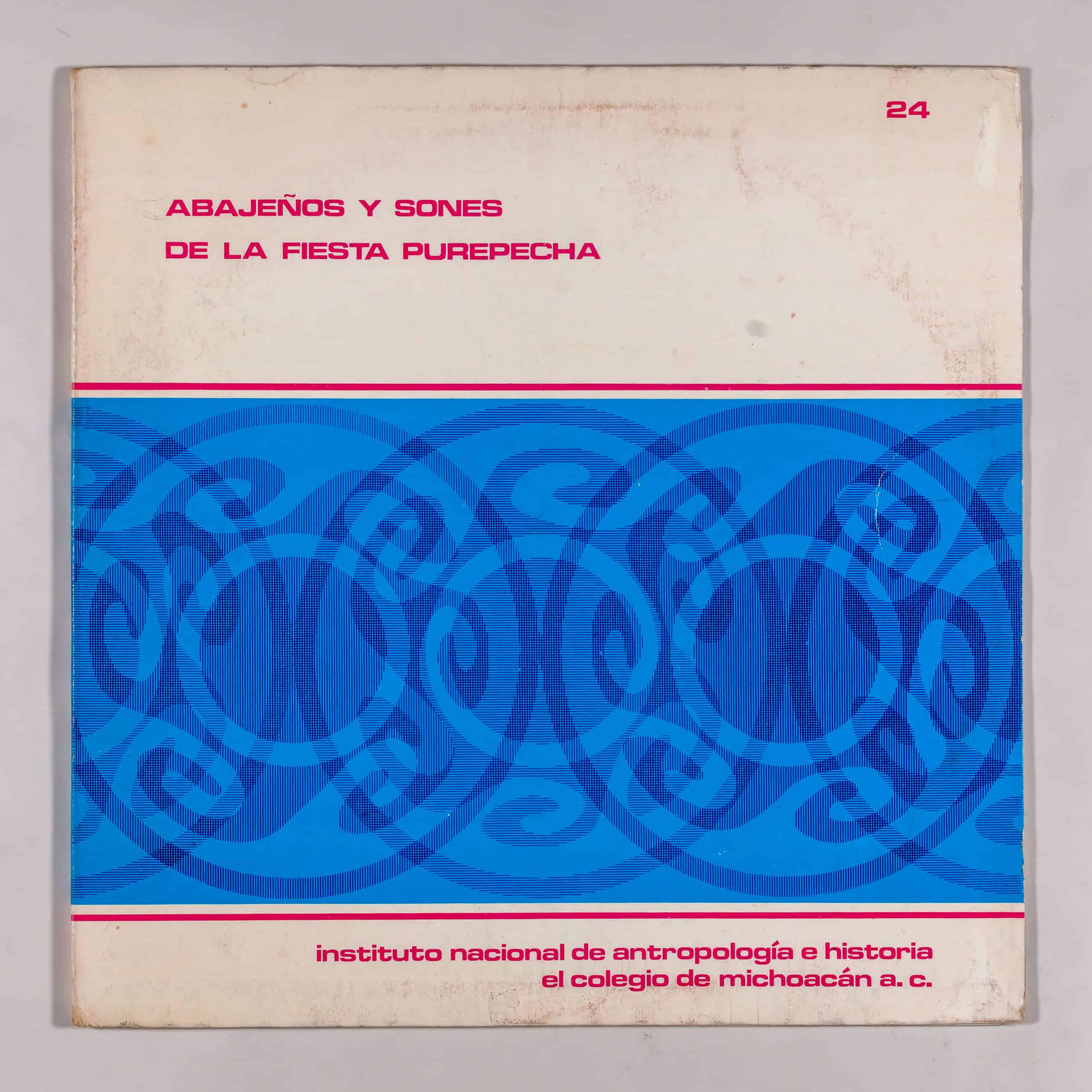

ABAJENOS AND SONES OF THE PUREPECHA PARTY

INAH SEP

|

Label: INAH-SEP INAH-24, LME-054 Released: 1981 |

Country: Mexico Genre: Abajeno Sound |

Info:

ABAJENOS AND SONES OF THE PUREPECHA PARTY

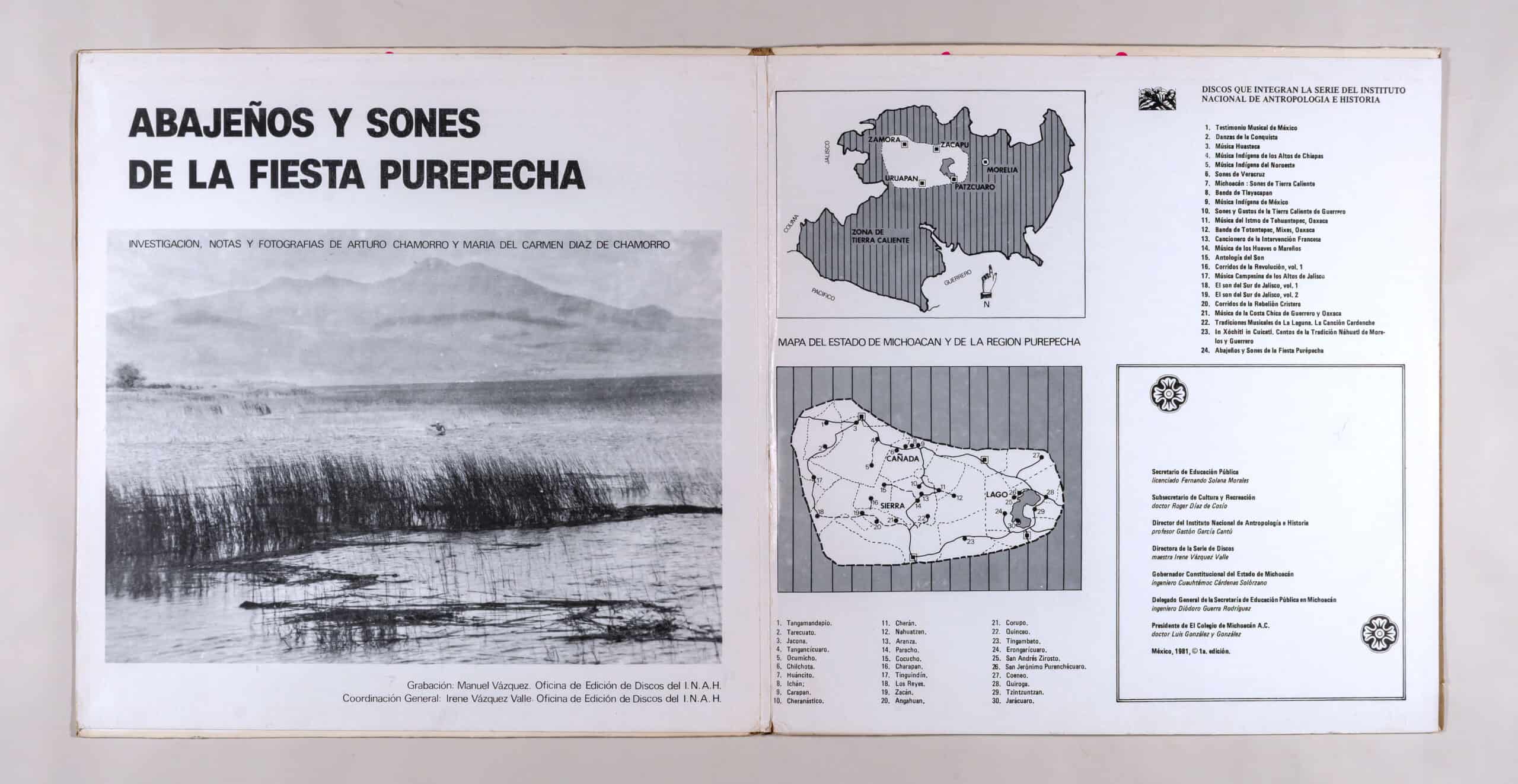

RESEARCH, NOTES AND PHOTOGRAPHS BY ARTURO CHAMORRO AND MARIA DEL CARMEN DIAZ DE CHAMORRO

The Festival

Talking about the traditional festival in Mexico involves serious problems for the scholar to delimit its own characteristics. In the first place, we would have to reduce the universe of study and start from our multicultural reality, differentiate the internal and external structure, the motivations of those who intervene in it and the attitudes assumed by them.

In the traditional religious festival we find a dual aspect that is interrelated with each other; On the one hand, there is the observance of the institutional liturgical ritual of the Catholic Church in its devotional practices (praises, masses, processions, pilgrimages, among others) and on the other hand, popular religiosity is manifested through cordel literature (printed ninths of anonymous authors and some prayers of a popular nature), the “mandas”, the visual expression of a penance, altars, vigils, presence of dance groups on the occasion of a “promise” that is fulfilled, for example, in the patronal festivals.

The traditional festival constitutes a multi-linked social fact that requires interdisciplinary tasks for its study. Its historical dimension offers bases to explain the processes of change in the social structure of a given region. Analyzed in its present time, it offers possibilities for multiple research in its anthropological, sociological, ethnomusicological and folklorological aspects, to mention some of the most related perspectives to understand the festival.

It has been said that the festival expresses the signs of a group’s cultural identity, and that when it manifests it reflects the existence of a community integrated into its living traditions. It is a way of encountering the heritage of past times that currently allows the expression of the particular sensitivity of our people and their appreciation of the world; it also reflects current cultural values and those that are in the process of transformation.¹

Civil, religious or traditional authorities can intervene in the organization of a party. In those where certain indigenous traits still predominate –such as language– the system of “charges” remains in force with greater frequency, compared to other festivals. Said system of ceremonial organization is expressed through the “stewardship” or the “cofradía”, understood as the solidarity group that is present at the festival and that in turn promotes social mobility.

Referring to the traditional popular festival is talking about a complicated system of interrelated elements. We could specify the concept of fiesta, as a complex of a folkloric type that, being also a social fact,² is subject to the processes of change inherent to the social structure of the group; It is a phenomenon that due to its dynamics is in constant transformation. Due to this reason, any celebration will never be repeated under the same conditions every year, so it will always offer new elements that may well lead to greater integration or promote the social disintegration of the community.

In this way, the sociocultural party complex is subjected to the so-called agents of change, whether internal (produced by the participants and organizers themselves) or external (television and radio channels, as well as certain entertainments of the consumer society that offer new entertainment expectations). The acculturation process will be present and the traditional festival will be maintained more or less as we know it, “until the day new ways of acquiring prestige and social control appear.”³

The Purepecha Festival

History tells us that the last wave of settlers in pre-Hispanic Michoacán was the Purepecha or Huanacase, also known as Tarascans, whose language was not related to the other Mesoamerican linguistic groups,⁴ although recent studies have it has found great similarity with other languages such as Zuni from the United States and Quechua from Peru.

The nominative Tarascan, apparently, is not accepted with great enthusiasm among the indigenous inhabitants of Michoacán who speak this language, as it is considered offensive. Despite the antiquity of this domination, some historians have preferred to use the demonym of Purepecha and, for the language, that of purembe or purhe. The concept of Purepecha tends to be associated with that of “common people”. As a gloss of the different meanings, the idea would come to be more or less: “people coming from other parts whose vocation is warrior and this has allowed them to acquire their own house where they move as a family.”⁵

People of divine origin coming from heaven, constituted on earth as a religious political state whose functions mainly attended the calendar of their religious festivals. “The festival in a certain sense comes to mark the rhythm of the existence of the Tarascan state… it has a religious character that is an expression of sacred time.”⁶

According to later studies based on the widely quoted Relación de Michoacán⁷, the name of the lunar months in their calendar coincided with that of a festival. Their social stratification was based on military, priestly, artisanal and commercial power; through which the acquisition of political or social prestige, depended to a large extent on participating in the organization of the festivities, and one of the economic functions of these came to be the communal distribution of accumulated wealth among the members of the locality and the visitors they receive.

The policy of evangelization in the New World is based on the traditions of each culture to take them as a vehicle for instruction and control. Michoacán is not the exception, the Michoacas or Purepechas throughout several generations that survived the catastrophe, had to hide a good part of their cultural past. The festival would remain in force, the purpose had also changed its officiants, but latently Curicaueri and Xaratanga accompanied by the other gods, still remained silent in the atmosphere of the new images and representations. Understanding the secular organization of the festival in Michoacán leads us to mention that depository institution for the organization of religious festivals: the brotherhood. Member of the traditional cargo system, which we will only approach superficially.

Of those medical care hospitals created for the indigenous sector towards the end of the 16th century, the foundation of the charitable-religious brotherhood is associated, both oriented with the double purpose of congregating Indians in one place and thereby facilitating their evangelization, at the same time that the required tribute was collected.

In the Province of Michoacán, the “hospital-fraternity” institution was implanted with singular results and beneficial fruits. The teaching of trades to Purepechas proliferates, which originates the grouping of guilds that in turn revolve around the brotherhood. The support is mutual, in the event of the death of one of its members, the funeral expenses are paid and the family is helped. Of the quota that they are obliged to cover, a large part is used to cover the expenses that the festivities entail in honor of the Patron Saint, to whom they were protected.

Of the most renowned celebrations due to the number of participating guilds, the Corpus stands out, prestigious for the huge processions with images carried on litters and the crowds that it brought together.⁸

The seed was sown, generation after generation the hierarchy of positions will be lived, from the elderly to the young the responsibility of attending to the titular and employer images is transferred. Despite the political changes that take place over time, the principle of organization that sustains the party continues. The brotherhood associated with the medical care hospital disappears to become a secular association, which in turn will come to be represented by the traditional council made up of the traditional authorities chosen for their wisdom or economic or social prestige.

Carrying out the position obtained is not easy, especially in times of political and economic crisis. On the other hand, the institution receives frequent attacks and criticism from the most radical priestly group, which tries to suppress “such waste” by collecting images and prohibiting the party, in order to disintegrate the council, not only because of its administration of the celebration, but also because it also represents a supportive group that exercises greater decision-making power among the community. If we add to this the poverty of the peasant and his debts inherited from father to son, many of those chosen for mayordomos or freighters, refuse to accept such responsibility knowing the heavy expenses that it entails; That is why there are cases of people who flee their community to avoid commitment, although some, despite everything, are forced to accept due to the strong social pressure to which they are subjected.

In many communities in the Purepecha region, the cargueros have come to mean the support base that was previously constituted by the brotherhood and its division of tasks. Nowadays it is affirmed that the traditional council is in the process of extinction; although it remains in those isolated places with difficult access, which tend to preserve their tradition. In the process of extinction, the attacks carried out by civil and religious authorities and by people from the same locality who accuse the collected funds of embezzling and brand the traditional organizers of the festival as drunkards intervene as factors. Also, the increase in the cost of living has caused them to refuse to receive a commitment that is already totally unaffordable.

There are places like Carapan and Huancito, corresponding to the Cañada de los Once Pueblos, where the organization of the festivities is done according to the division of neighborhoods, through the election of a commissioner in charge of making the collection, house by house; each neighborhood covers the expenses of the music, the castle, the food, the mass and the arrangement of the altar separately. Generally, those who participate are individuals of both sexes, who since childhood have always participated in activities of a traditional nature in the region and who in turn inherited the task and the “taste for fulfilling the saints” through the family line.

Rasgos Particulares

La fiesta tradicional purepecha actualmente está sujeta a presiones de diversa índole, sobre todo de tipo económico. Durante nuestro recorrido era muy común que los habitantes ancianos de la región recordaran tiempos pasados de bonanza, entusiasmo y respeto. Mucho se ha perdido a raíz de la desaparición del cabildo.

La porción circundante al lago de Pátzcuaro en su parte oriental, tal vez sea de las que más transformaciones haya tenido; el turismo le exige espectáculos a cambio del ingreso que aporta durante su estancia, sacrificando la tradición. Tal vez las riberas occidentales del Lago, sean las que por su aislamiento, aún presenten sus fiestas con buena parte de la tradición purepecha. Erongaricuaro por ejemplo, todavía conserva su carguero y capillas de culto. En su fiesta patronal del “Señor de la Misericordia”, el seis de enero, se contrataron dos bandas de música y se presentó una danza de Santiagos, que fue reforzada por otra igual procedente de Pátzcuaro. Hubo “castillo” y corrida de toros, también muchachas vestidas de uares (con blusa bordada y falda tableada de lana negra). Habló por sí solo el esfuerzo de su carguero en esta fiesta mestiza sin ceremonia indígena que refleja la tradición de la mayordomía; pese a que su población de pescadores y hablantes bilingües ya no se considera a sí misma indígena.

Y así podríamos seguir hablando de cada una de las fiestas que fueron registradas en el Lago de Pátzcuaro, la Sierra y la Cañada de los Once Pueblos, sin embargo, no podemos pasar por alto la variedad de rasgos culturales que se presentaron a lo largo del registro musical de la fiesta. Michoacán tal vez sea el estado que más fiestas tradicionales tenga en su geografía; tan solo la región purepecha tiene un promedio de tres a seis fiestas grandes al año por comunidad.

La crisis del cabildo tradicional se supera con el nombramiento del carguero y de los comisionados que deberán ayudarle a hospedar a los miembros de la banda y conseguir la comida en varias casas.

El peso económico se aligera un tanto por las colectas y ayudas en especie (maíz, frijol, carne) que otros vecinos “han prometido como manda mientras vivían para servir al santito.”

Si hay eficiencia entre los colaboradores de las “colectas” y apoyo de las autoridades civiles, se pueden organizar concursos. Estos concursos últimamente han adquirido mucha popularidad y aceptación en la zona, sus premios llegan de dos a tres mil pesos, y por lo general se orientan hacia la promoción de solistas y grupos de cantadores de pirekuas así como de orquestas.

El arreglo del templo es una tarea común, con anterioridad se delimitan responsabilidades y desde la víspera hombres y niños decoran el templo. Si aún pervive la cofradía de alguna imagen, los cofrades, tienen la obligación de arreglar su imagen. Para el día de la fiesta, la mayor parte de las imágenes de bulto estrenan vestido, y a veces dos o más (como ha sucedido en Urapicho, donde pusieron los cinco vestidos que le regalaron a la Virgen y sus respectivos mantos).

Aun cuando no haya un solo carguero, las comunidades se reparten el peso del compromiso por barrios. Así uno de los cuatro barrios o cuarteles costean la música de Banda, otro el castillo, otro el novenario y las misas y otro las comidas; nuevamente observamos como se presenta la participación comunitaria.

La presencia o ausencia de un grupo de danza o teatro folklórico puede originarse por múltiples causas, la más común es la desintegración del grupo local. Hay casos como el de Erongarícuaro, en que el grupo formado para ese año, se reforzó con la invitación de los Santiagueros de Pátzcuaro, como referimos anteriormente. O bien, puede ser que se considere el lugar de visita obligada por una “manda”, como lo fue la pastorela de Paracho, que asistió a Cocucho para rendir culto a la Purísima. Cabe mencionar que a esta fiesta se le da una gran importancia en la región, pues, por ejemplo, desde la víspera se dieron cita aproximadamente 20 grupos de pastorelas y viejitos, que actuaron entre los casi tres mil visitantes que acudieron a esta fiesta indígena.

La mejor tarjeta de presentación de un grupo es el modo de actuación en una fiesta, así, las danzas y pastorelas se esmeran en estrenar ropa y contratar al mejor grupo para que ejecute los sonecitos; y en ese cuidado las bandas no son la excepción. Según sea la importancia del compromiso, algunas bandas se refuerzan con otros elementos de instrumentistas de la misma comunidad o por la relación de amistad, sobre todo si se menciona que estarán frente a otra banda; el prestigio del grupo tiene que mantenerse muy en alto, es común que durante las fiestas se enfrenten unos y otros en las competencias o encuentros.

Uno de los dos grupos le “tiene que poner la mano” –musicalmente hablando– a su oponente. Esta competencia señala la hora de mayor afluencia de visitantes a la comunidad y generalmente sucede antes de la quema del “castillo”. Se sabe de antemano que del éxito del grupo dependen algunas invitaciones para tocar en otras fiestas. Es el momento en que la tradición musical aflora sin presiones, abajeño tras abajeño, exigen de una entrega absoluta. Es el clímax de la fiesta, finaliza así el primer día con el torito de luces pirotécnicas y el “castillo” de más de quince metros de altura.

Cada familia, en la medida de sus posibilidades, trata de vivir la fiesta en casa. Es tradición estrenar para ese día sobre todo las jóvenes casaderas. Hay quienes estrenan rebozo, zapatos, el uanengo o blusa, y si es comunidad indígena, se presenta la ocasión de lucir el mejor rollo tableado (falda de lana plegada).

Ellos también estrenan, posiblemente sea la mejor oportunidad de encontrar quien será su compañera.

En las casas indígenas, los preparativos empiezan desde una semana antes; los dos o tres días anteriores a la fiesta llegan las sobrinas o ahijadas a ayudar en la cocina. En toda fiesta purepecha no faltan las Korundas (tamales sin carne) y el sabroso churipo (caldo rojo enchilado que lleva perejil, col hervida y carne de res en trozos). Se preparan grandes cantidades, puesto que ese día llegarán los familiares y amigos de otros lugares y tal vez, aquel conocido que salió a la frontera o vive en otras regiones del país. También son recibidos los inesperados, según un refrán tradicional de la región, porque “cuando hay fiesta todo mundo es pariente.”

A lo largo de nuestras experiencias en el campo, iniciadas en la región purepecha desde la Semana Santa de 1980, hemos comprobado la permanencia de valores tradicionales que integran más a las comunidades indígenas que a las no indígenas, en estas últimas impera más la adquisición de prestigio a través del cargo; las diversiones de tipo mecánico, de azar y otras más que dejan buenos ingresos. Se constituye así uno de los procesos que transforma a la fiesta tradicional; con cabildo o sin él, tal vez con reminiscencias de lo que antaño era la ceremonia de sus ancestros. De la fiesta purepecha aún podemos afirmar que su transformación será lenta y tal vez el siguiente año dé un giro más. Lo que es un hecho es la permanencia de la ayuda solidaria ante las responsabilidades, como una tarea comunal.

Purepecha Music, its origins

The oldest references to Purepecha music have been found through archaeological finds from Chavinda, San Pedro Caro and Tzintzuntzan (capital of the Old Tarascan Empire). Numerous collections have been formed from these finds that preserve Preclassic copper and clay specimens of whistles, rattles, snails, ocarinas and flutes. A large part of this pre-Hispanic heritage is currently preserved in the Michoacano Museum of Morelia and the Municipal Museum of Uruapan.

Daniel Castañeda⁹ contributes a valuable study to the knowledge of clay flutes, described by him as aerophones equipped with tubes with four holes, from which scales of the pentatonic range (with five sounds) are derived. This characteristic has been identified not only in Purepecha specimens, but also in certain flutes from the Aztec and Inca cultures.

The chronicles and documents of the 16th century also tell us about the music and instrumental endowment in our area of study. In particular, La Relación de Michoacán¹⁰ mentions the existence of sound instruments in the festivities and ceremonies in honor of the Cazonci or King Purepecha, who was venerated with the music of snails, flutes, pavilion aerophones (rudimentary trumpets), turtle shells and drums. made of wood or kuiringuas.¹¹ The latter were identified in the Hispanic world under the name of “atabales”.

A fragment of La Relación de Michoacán, in which the details of the ceremony on the occasion of the death of the Cazonci are described, highlights the importance of musical instruments in ritual function:¹²

“Chapter XVII. How the cazonci died and the ceremonies with which they buried him………………… And he also brought a dancer and a player from their drums and a carpenter of his drums. And other his servants wanted to go and they would not let them go; they said that they had eaten his bread and that perhaps he would not treat them like him, the lord that he would be.

They all put garlands on their heads of clover and their faces turned yellow and they went tolling in front: one, some alligator bones, others some turtles”.

The Mesoamerican Purepecha society always maintained its full festive and ceremonial tradition in sound manifestations with an artistic-musical touch. When establishing contact with the Hispanic world, the European ear must have associated the playing of instruments with its own conception of “music”, a term that does not appear in the Spanish translations of the oldest words of the Purepecha language, for which reason He believes that the sound element of musical instruments has actually been identified as a synonym for party¹³ and ceremony, transformed into Christian worship services during the Colony.

The manufacture of musical instruments has been one of the most important tasks of the Purepecha artisan, who not only designed flutes, ocarinas, whistles, rattles and wooden drums in his pre-Hispanic period, but also devoted himself to the tasks of learning the construction of European instruments, in which he became a notable performer and composer.

Robert Stevenson¹⁴ refers to the first artisan centers founded around the year 1586, one in Pátzcuaro, which stood out for the manufacture of bells, trumpets, flutes and oboes, distributed throughout New Spain; the other center in Tzintzuntzan that specialized in the manufacture of trumpets and shawms.

Some colonial paintings from the 17th and 18th centuries, which can be seen in the vaults of the oldest Catholic temples in the region, also refer us to the introduction through worship and religious services of other instruments learned and designed by the indigenous hand, such as vihuelas de arco, vihuelas de mano, guitars, violas, violins, rebec, harps, lutes and lyres.

The old master luthiers from the old world, left the seed in the times of Don Vasco de Quiroga’s Michoacán, which sprouts in the Purepecha disciples, who from the Colony have developed in their own style, the art of tolling and the construction of instruments.

Regarding Paracho, as the third artisan center of great importance for the musical history of Michoacán, it should be noted that its production has been maintained since the Colonial Era.

We have not precisely identified the opening of the luthiery workshops, however we will mention that one of the most prolific stages of this art in San Pedro Paracho, dates back to the 18th century, in which there is talk of the existence of 204 indigenous tributaries experts in the tasks of designing vihuelas and violins.¹⁵

Festive Background of the Son in Mexico

The Dictionary of the Royal Spanish Academy, states that they are, comes from the Latin sonus and defines it as “arranged (organized) noise that we perceive with the ear, especially that which is made with art or music.”¹⁶

This idea of concerted noise is also associated with the term “tune” or execution of an instrument and apparently is equivalent to the Latin sonus, which is also sound, an essential element of music.

In Mexico, the son is understood as a form of song and dance music, in whose structure organizations of instruments, verses or couplets and the elemental tap dance of dance are appreciated.

The origin of this genre goes back to the Colony, from which the traditions and customs of three worlds, the Hispanic, the African and the indigenous, were shaped, resulting in a hybridization of lyrical, instrumental and choreographic forms, considered for the European taste and the Inquisition as “obscene and anticlerical”, for which reason they were frequently prohibited, both at the level of the colonial government and by the religious authorities.

It is perhaps this official prohibition, which motivated a greater acceptance and deep roots of the collective and public manifestations of music, song and dance, among the exploited people of New Spain.

Apparently, these demonstrations, which were called “popular sounds”, have played an important role in the festive life of the colony, with different nominations.

Towards the end of the 16th century, for example, the sones were introduced in religious-popular festivities called colloquiums and towards the second half of the 17th century, massive groups of blacks and mestizos were also incorporated into a certain type of celebrations, called oratorios, where allowed them to carry out their religious events, with the accompaniment of prayers, dances and instrumental groups with harps and guitars.¹⁷

In this same period, other types of festivals arose, known as scapulars, which were in charge of ridiculing saints, through certain insinuating dances. It is to be expected that they have received the heavy hand of the Inquisition. It was not until the end of the 18th century, when the religious authorities gave up a little on their prohibitions, to accept the festive gatherings, in which mestizos, blacks and indigenous people participate, and in which the music of sones and syrups is incorporated.

Apparently, the African influence was felt with great power in the music of sones and jarabes, especially in what refers to the incorporation of the combined rhythms that were derived from the ancient sarabandas or sarabandas dances, introduced in Spain during the Moorish domination and later transferred to Mexico. From these dances, the rhythms known as sesquialteros are born, which result from the combination of measures in 6 by 8 and 3 by 4, which constitute the very basis of the Mexican son.¹⁸

Regarding the role of the son, in other types of collective manifestations of a festive nature, Vicente T. Mendoza places special emphasis on the close relationship it has with the scenic tune, of which there is news from the second half of the 18th century.¹⁹ We can understand this representation as a form of popular theater that included an intermission with music.

The forms of popular theater have received different names. For example, those performances that did not have music were known as sainetes or hors d’oeuvres, but when the son was incorporated, they were called tonadillas,²⁰ which are believed to have arisen as a reaction of Spanish-speaking people against the Italian Opera who became famous among the aristocracy.

In the period of Independence, a new stage in the evolution of the son is marked, since it becomes part of the national soul, as a result of the popularity it had through theater in the Spanish language. This is how the first piano transcriptions of the distinctive sounds of each region emerged in the 19th century, which were called “national airs”.²¹

With the Revolutionary Movement of 1910, the son became definitively integrated into the Mexican essence of the peasant in struggle, in contrast to the Mexican upper classes who persisted in their taste for European fashion. As a result of this period of conflict, the son continues its march towards the encounter with the mestizo soul, represented in the most popular ensembles such as the mariachi and the large harp ensemble, among others, from which spring the new regional styles of our century.

General aspects of michoacano son

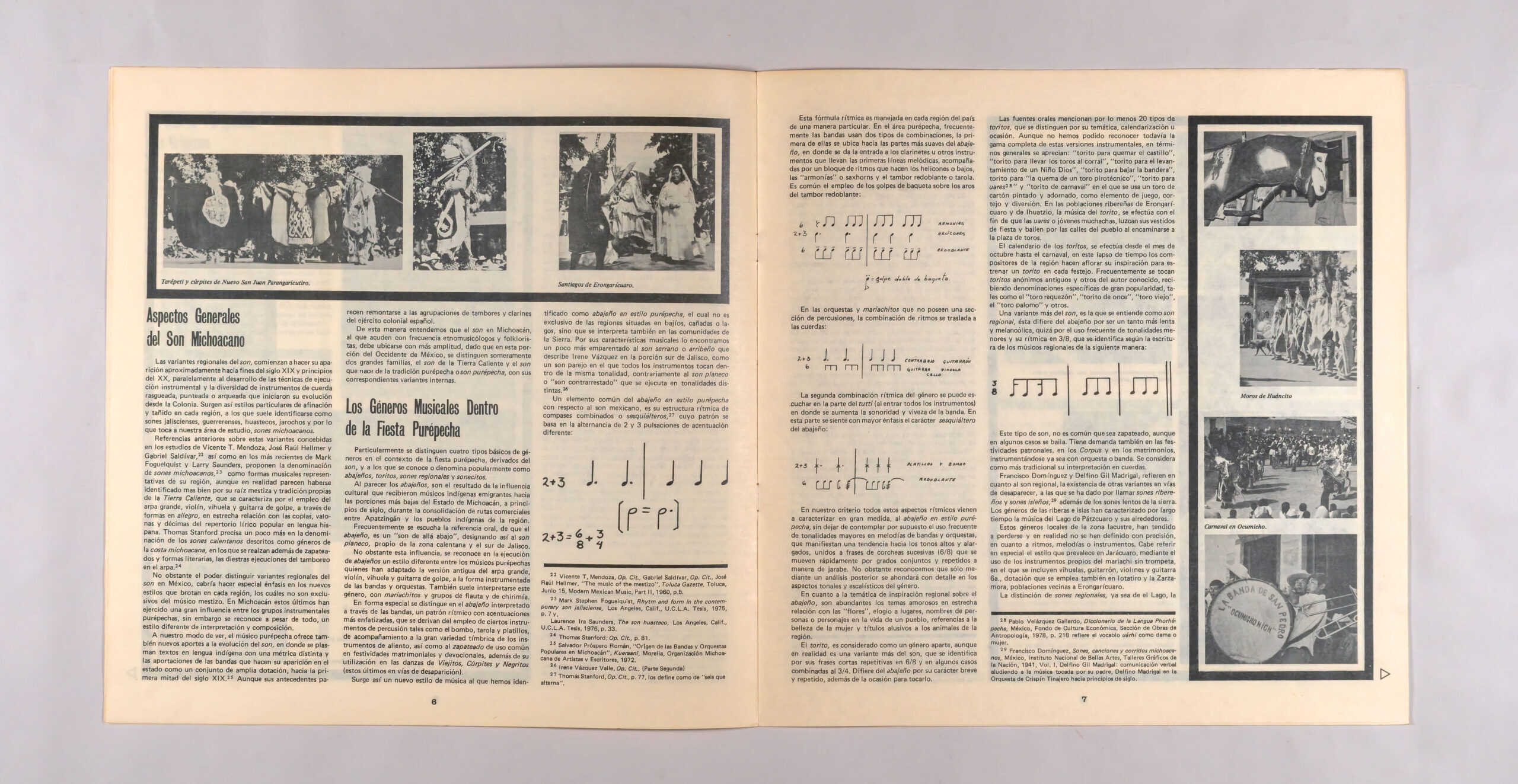

The regional variants of the son began to appear approximately towards the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, parallel to the development of instrumental performance techniques and the diversity of strummed, plucked or bowed string instruments that began their evolution from the Colony. . Thus, particular styles of tuning and tolling arise in each region, which are usually identified as sones from Jalisco, Guerrero, Huastecos, Jarochos, and as far as our area of study is concerned, sones from Michoacán.

Previous references on these variants conceived in the studies of Vicente T. Mendoza, José Raúl Hellmer and Gabriel Saldívar,²² as well as in the most recent ones by Mark Foguelquist and Larry Saunders, propose the denomination of Michoacan sones,²³ as representative musical forms of their region, although in reality they seem to have been identified rather by their mestizo roots and tradition typical of Tierra Caliente, which is characterized by the use of the large harp, violin, vihuela and guitarra de golpe, through forms in allegro, closely related with the coplas, valonas and tenths of the popular lyrical repertoire in the Spanish language. Thomas Stanford specifies a little more in the denomination of the calentanos sones described as genres of the Michoacán coast, in which the skilful executions of drumming on the harp are enhanced, in addition to foot-stomping and literary forms.²⁴

Despite being able to distinguish regional variants of the son in Mexico, special emphasis should be placed on the new styles that emerge in each region, which are not exclusive to the mestizo musician. In Michoacán the latter have exerted a great influence among the Purepecha instrumental groups, however, despite everything, a different style of interpretation and composition is recognized.

In our view, the Purepecha musician also offers new contributions to the evolution of the son, where texts in the indigenous language are captured with a different metric and the contributions of the bands that make their appearance in the state as a well-equipped ensemble. , around the first half of the 19th century.²⁵ Although its background seems to go back to the drum and bugle groups of the Spanish colonial army. In this way, we understand that the son in Michoacán, which is frequently attended by ethnomusicologists and folklorists, should be located more broadly, since in this portion of western Mexico, two great families can be distinguished, the son of Tierra Caliente and the son of Tierra Caliente. They are born from the Purepecha tradition or they are Purepecha, with their corresponding internal variants.

Musical genres within the purepecha festival

In particular, four basic types of genres are distinguished in the context of the Purepecha festival, derived from the son, and which are popularly known or called as abajeños, toritos, regional sones and sonecitos.

Apparently, the abajeños are the result of the cultural influence that emigrant indigenous musicians received towards the lower portions of the State of Michoacán, at the beginning of the century, during the consolidation of trade routes between Apatzingán and the indigenous peoples of the region.

Frequently the oral reference is heard, that the abajeño, is a “son from down there”, thus designating the son planeco, typical of the calentana zone and the south of Jalisco.

Despite this influence, a different style is recognized in the execution of abajeños among the Purepecha musicians who have adapted the old version of the large harp, violin, vihuela and guitarra de golpe, to the instrumental form of bands and orchestras. This genre is also usually interpreted, with mariachitos and flute and shawm groups.

In a special way, the abajeño interpreted through the bands is distinguished, a rhythmic pattern with more emphasized accentuations, which derive from the use of certain percussion instruments such as the bass drum, snare drum and cymbals, to accompany the great variety of timbres of breath instruments, as well as the tap dance commonly used in marriage and devotional festivities, in addition to its use in the dances of Viejitos, Curpites and Negritos (the latter in the process of disappearing).

Thus, a new style of music arises that we have identified as abajeño in the Purepecha style, which is not exclusive to the regions located in shoals, ravines or lakes, but is also performed in the communities of the Sierra. Due to its musical characteristics we find it a little more related to the serrano or arribeño son that Irene Vázquez describes in the southern portion of Jalisco, as an even son in which all the instruments play within the same tonality, contrary to the son planeco or “son countered” which is performed in different keys.²⁶

A common element of the abajeño in the Purepecha style with respect to the Mexican son is its rhythmic structure of combined or sesquialteros measures,²⁷ whose pattern is based on the alternation of 2 and 3 beats with different accentuation:

This rhythmic formula is handled in each region of the country in a particular way. In the Purepecha area, the bands frequently use two types of combinations, the first of which is located towards the softer parts of the abajeño, where the clarinets or other instruments that carry the first melodic lines are introduced, accompanied by a block of rhythms that make the helicones or basses, the “harmonies” or saxhorns and the snare drum or tarola. It is common to use the beats of the stick on the sides of the snare drum:

In orchestras and mariachi bands that do not have a percussion section, the combination of rhythms is transferred to the strings:

The second rhythmic combination of the genre can be heard in the tutti part (when all the instruments enter) where the sound and liveliness of the band is increased. In this part, the sesquialtero character of the abajeño is felt with greater emphasis:

In our opinion, all these rhythmic aspects come to characterize, to a great extent, the abajeño in the Purépecha style, without forgetting, of course, the frequent use of major tonalities in band and orchestra melodies, which show a tendency towards high and elongated tones. together with phrases of successive eighth notes (6/8) that move rapidly by joint and repeated degrees like syrup. However, we recognize that only through a subsequent analysis will the tonal and scale aspects of the genre be delved into detail.

Regarding the theme of regional inspiration on the abajeño, there are abundant love themes closely related to “flowers”, praise to places, names of people or characters in the life of a town, references to the beauty of women and titles alluding to the animals of the region.

The torito is considered a separate genre, although in reality it is one more variant of the son, which is identified by its repetitive short phrases in 6/8 and in some cases combined in 3/4. It differs from the abajeño because of its brief and repeated character, as well as the occasion to play it.

Oral sources mention at least 20 types of bulls, which are distinguished by their theme, calendar or occasion. Although we have not yet been able to recognize the full range of these instrumental versions, in general terms we appreciate: “little bull to burn the castle”, “little bull to take the bulls to the corral”, “little bull to raise a Child God”, ” bull to lower the flag”, bull for “the burning of a pyrotechnic bull”, “bull for uares”²⁸ and “carnival bull” in which a painted and decorated cardboard bull is used, as an element of play, courtship and fun. In the riverside towns of Erongaricuaro and Ihuatzio, the music of the little bull is performed so that the uares or young girls wear their party dresses and dance through the streets of the town on their way to the bullring.

The calendar of the bulls, takes place from the month of October until the carnival, in this period of time the composers of the region bring out their inspiration to release a bull in each celebration. Anonymous ancient bulls and others by a well-known author are often played, receiving specific names of great popularity, such as the “requesón bull”, “eleven bull”, “old bull”, the “pigeon bull” and others.

One more variant of the son, is the one that is understood as regional son, this differs from the abajeño because it is somewhat slower and more melancholic, perhaps due to the frequent use of minor tonalities and its rhythmic in 3/8, which is identified according to the writing of the regional musicians as follows:

It is not common for this type of son to be zapateado, although in some cases it is danced. It is also in demand at patron saint festivities, at Corpus Christi and at weddings, being instrumented either with an orchestra or a band. Its interpretation in strings is considered as more traditional.

Francisco Domínguez and Delfino Gil Madrigal, refer to the regional son, the existence of other variants in the process of disappearing, which have been called river sones and island sones,²⁹ in addition to the slow sones of the mountains. The genres of the shores and islands have long characterized the music of Lake Pátzcuaro and its surroundings.

These local genres of the lake area have tended to get lost and have not really been precisely defined in terms of rhythms, melodies or instruments. It is worth mentioning in particular the style that prevails in Jaracuaro, through the use of the typical instruments of the mariachi without trumpet, which include vihuelas, guitarrón, violins and 6th guitar, an endowment that is also used in Lotatiro and La Zarzamora, towns neighboring Erongaricuaro.

The distinction of regional sounds, whether from the Lake, the Cañada or the Sierra, is established by the musicians themselves under the concept of “the taste of each town”.

As for the little sonecito so called popularly, it is integrated into the repertoire of solo instruments such as the reed flute or the shawm, although it is also part of the orchestras, bands and mariachios that accompany “sones de corte de danza”, whose theme is derived of the choreographic movements, such as: “the cross”, “the reverence”, “the clapping”, “the chain”, “the snail”, etc.

Its musical structure tends to be of short melodies in 8-bar phrases, generally repeated constantly. For the little sonecito, binary measures are used in 2/4 or 4/4; 6/8 is used more for the repertoire of abajeños played on flute and shawm. It should be clarified that certain abajeños also accompany some dances and are similar to sonecitos due to their brief and repetitive structure, although due to their rhythm they are quite different. The sonecito rarely presents a sesquialtera combination.

This reduced genre is more associated with the religious ceremonial of the festival than with its profane aspect, usually the dances that carry sonecitos, are characterized by their “offering” or “promise”. On the other hand, the solo instruments of flutes and chirimiteros, who interpret the genre, are normally incorporated into the structure of Corpus Christi and patron saint festivities in church atriums. As for the Purepecha carnival, it has not been specified if it is absolutely profane, since manifestations of dance and music accompanied by little sounds are appreciated in it, which seem truly ritual.

Reviewing the theme of regional sones and sonecitos, a preferential use of titles alluding to the regional flower or TSATSA’Ki is discovered, differentiating its species and different denominations such as “flor de tule”, “flor del bean”, “flor de chicalote “, “dahlia flower”, “poppy flower”. “charanguini flower”, “cinnamon flower”, etc. This theme is also common in the pirekua³⁰ or traditional form of song in the Purepecha language in which the divine beauty of the flower with a deep spiritual meaning is highlighted.

We find in this symbolism of themes referring to flowers, ancient Mesoamerican roots of great similarity with the duality “flower song”, embodied in Nahuatl poetry and in some of the deities of the Aztec world such as Xochipilli-Macuilxóchitl, representative of music and dance. .

In conclusion, most of the Purepecha genres are interpreted within the scope of the festival, such as sones, tortos and abajeños by a well-known author, there are also those by an anonymous author, although they are truly rare. Socio-economic relations have somehow contributed to the enrichment of musical experiences between Purepechas and mestizos. The Purepecha musician in particular has used his great inventiveness and talent to develop the elementary techniques of harmony and rhythm.

The role of the regional composer is equally important, since he is in great demand in festive events of greater social and religious relevance. The fresh sounds that spring from each new son redound to the benefit of a social prestige eagerly sought by creators and performers before the Purepecha community.

Current Instrumental Organization

In our study region we have found five types of instrumental ensembles that remain in force, even when some of them are about to disappear. They are popularly identified as the band, the orchestra among the most numerous groups, continuing to a lesser extent the mariachi or mariachito and finally the small groups of solo and accompaniment instruments, made up of duos, trios and quartets better known as flute ensembles. and drum or pifaneros and shawm and drum or chirimiteros.

These small groups of aerophones are recognized as the oldest in Michoacán. With regard to the flute and drum ensemble, the influences of two cultures are obvious: the Hispanic one represented in the snare drum and the Mesoamerican one in the reed flute, despite its European name of fife.

In our fieldwork itineraries, we have found isolated references to the validity of this group and mainly to the survival of the reed flute in San Andrés Tziróndaro, Jarácuaro, Cucuchucho, Zopoco, Carapan and Cherán Atzícurin. The most common examples of this type of aerophones are provided with 6 holes, which normally reproduce pentatonic scales (with 5 sounds) through thick and thin tubes manufactured with the reed or p’atamu (Arundo Donax L.)³¹ that grows in the lake area of Pátzcuaro.

The musicians of the region distinguish at least two types of flutes for festive use, differentiated as “first” by its high-pitched tone and thin tube, which alternates with the “second” with a lower or lower tone and wide tube.

Generally, the musicians who play this type of aerophones are also manufacturers and learn to build and play them as children, forming part of their game and pastime. Later, when going through adolescence and maturity, the function of the flute changes when it becomes an instrument for ritual use, thus completing an important phase in the indigenous life cycle.

As for the snare drum, it is a type of membranophone with a wide wooden or sheet metal box, provided with two skins made of calf or goat skin, with an addition of guitar strings. These serve as a snare that is vibrated by resonance as seen in military or war drums.

It is also known as snare or “tarolita”, depending on the thickness or width of the sound box. It is struck with a pair of drumsticks or sticks and is held by a leather or ixtle strap to the performer’s body. The tuning is done by means of a tension system provided by the tied ixtle ropes, said tuning is generally in high pitches, stretching the leathers to the maximum, thus allowing the musician to make his “rolls”.

It is common to observe the participation of the flute and drum ensemble on ceremonial occasions of a Corpus or to accompany the chanantzcua or Carnival dance, in which the shawm groups also dabble.

In their organization, the chirimiteros are very similar to the group of pifaneros, since they are made up of an aerophone and a snare drum, the difference is noticeable in the characteristics of sound and design of the wind instruments. Among the chirimiteros, the particular use of a double-reed aerophone (mouthpiece system) grouped in duets, trios or solo, accompanied by snare or “tarolita” can be distinguished.

According to testimonial chronicles and paintings from the Colony, the shawm seems to have entered through the paths of worship and religious services, which can be seen in the vaults of the oldest Christian temples.

Despite its Hispanic introduction in Michoacán, we recognize that the instrument presents a greater antiquity, which goes back to the Islamic tradition. This is explained by the evident influence of the Moors who dominated Spain for more than 700 years.

Among the families of Islamic instruments in which there is an extraordinary resemblance to shawms, we will mention the double-reed bagpipes traditionally used in the Middle East, known as Surnai,³² also equipped with a pavilion system at the end opposite the mouthpiece, as in the European oboe.

The shawm is made regionally in madroño wood, (Madronillo)³³ provided with 8 and 9 holes, in the artisan workshops of Paracho and Ahuiran, to which musicians normally resort to buy the tube of the instrument.

At home, the mouthpiece or mouthpiece is manufactured, in which process two strips measured approximately the width of four fingers are selected from the palm or chuspata (Cyperus), to be cut into four small pieces that are soaked in hot water softening them. . Once this is done, they are cut and tied into cannulas of the feathers of the turkey or another bird, to an approximate size of five centimeters. As in the oboe and English horn mouthpieces, they are moistened with the lips to give them an adequate sound.

Frequently the chirimiteros participate in religious organizations as essential elements in the atriums of churches, also during Corpus Christi and patron saint festivities at the invitation of the freighters on duty. During the Colony, these instruments used to accompany the dances of Moors and Christians³⁵ that today are accompanied by bands.

Regarding the well-equipped ensembles, the orchestras correspond to the instrumental group of the most colonial tradition. Among the Purépecha musicians, the orchestra is conceived in two ways, one for its exclusively stringed instruments and the other as a mixed group that includes chordophones and aerophones.

String orchestras generally use two or more violins, a 3- or 4-string double bass, sixth guitar, five-string vihuela, and cello, which reminds us of “chamber” music groups and certain Venetian orchestras of the 17th century, which also included the harp.

Comparatively, the mixed orchestras, in addition to the European string instruments, expand their endowment with clarinets in Bb (B flat) or Eb (E flat), transverse flutes in C (Do), alto saxophones in Eb and tenors in Bb, piston trombones in C and French horns frequently replaced by small Saxhorns in Eb or Bb, which are also known as “harmonies” or “euphoniums”.

Through references by Carl Lumholtz³⁶ there are reports of Purépecha orchestras at parties, weddings and wakes in times of the Porfiriato, a time in which they acquired prestige and social demand. Still towards the beginning of the century these orchestras maintained their fame.

Delfino Gil Madrigal cites, for example, the prestigious Crispin Tinajero orchestra in Erongarícuaro, which was known throughout the entire portion of Lake Pátzcuaro and of which his father Don was a part. Delfino Madrigal, playing the trombone, along with violins, cellos and double basses.³⁷

The maestro Salvador Próspero also alludes to the former orchestras of Tata Cruz Jacobo and J. Jesús Zavala in Sevina, as well as those of the brothers Nicolás and Alejandro Juárez in Jarácuaro; that of Don Epitacio Equihua in Aranza and that of Francisco Salmerón Equihua among others.³⁸

We would not do justice if we failed to mention the great orchestra led by José Santos Campos and Lambertino Campos, which is currently, as a posthumous tribute, in the process of being reorganized by their descendants, highly talented musicians in Zacán.

The role of the Purépecha orchestra has remained faithful to the Corpus tradition since the colonial period, in which it also accompanied dances, patron saint festivities and wedding celebrations.

As for the mariachi or “mariachito”, as it is known in the context of the regional festival, it is in itself another string group, although its characteristic endowment is given by the 6-string guitarrón, which appears as a rhythmic bass and in which finds a remarkable similarity with the chitarrone or archlute of Venice.³⁹

Even though the mariachi seems to come from the times of the Maximilian Empire, around 1870 in our country, the incorporation of the trumpet did not occur until the 20th century.⁴⁰ The presence of the mariachi in the Purépecha tradition denotes a marked influence of the mestizo ensembles that arise in Colima, Jalisco and Michoacán, especially in Uruapan, Purépero, Camécuaro, Zamora, Sahuayo and Jiquilpan.

The mariachi or mariachito plays regularly to accompany the dances within devotional festivities; Among the oldest dances, those of Viejitos, Santiagos and the “dance in honor of the Lord of Rescue” that takes place in Tzintzuntzan with a similar group stand out.⁴¹

As previously mentioned, Paracho has been the main supply center for string groups since the 18th century and especially for the mariachi of western Mexico and other string ensembles in the republic.

Without delving into the artisan aspects, we will mention the main woods commonly used in the manufacture of chordophones. Regarding the design of violins, cellos and double basses, the woods⁴² of Pinabeto (Pinus Ponderosa, Pseudosuga Mucronata and Cupressus Arizonica) are appreciated for the soundboards; blackwood (Agonandre O. St.) for pegs; the oak (Quercus, Trel.) for the neck of the “bows” to which nylon or horsehair strings are also adapted; pine (Abies Rel.) for bridges and steel or nylon strings.

Regarding the manufacture of vihuelas, guitars and guitarrones, the granadillo and cedar (Cupressus, Cedrela Dugesii) in pegs; tacote (Lagrezia Monusperma) for tapas; the pine for the “arms”, the red cedar for the resonance boxes, the common cedar for bridges; nylon or metal strings and some cirimo inlays (Tilia Houghi).

Finally, we will refer to the band as the largest group and the one with the greatest current demand in the Purépecha festival. In our view, this group, due to its sound impact, has tended to overshadow the participation of the orchestras in popular demand, although no less important for that.

The history of the band goes back in Michoacán to the old groups of drummers and trumpet players who used to participate accompanying the old dances of Moors and Christians.⁴³ However, it was not until the first half of the 19th century, when Austrian bands became more popular,⁴⁴ It is when its endowment is expanded with more sophisticated instruments.

The instruments that make up the band can be divided into circular mouthpiece instruments, reed instruments and percussion instruments:

- Circular mouthpiece instruments

Trumpets in Bb (B flat)

Piston trombone in C(Do) or in Bb(B flat)

Slide trombone in C 6 an Bb

Alto Saxhorn in Eb (E flat)

Baritone Saxhorn in Bb

Tenor Saxhorn in Bb

Tuba or helicon in C or in Bb

- Single reed instruments

Eb Clarinet

Bb Clarinet

Alto saxophone in Eb

Tenor saxophone in Bb

Soprano saxophone in Bb

Baritone saxophone in Eb

- Percussion instruments

Drum or bass drum

crash cymbals

Snare or snare drum

(of fabric)

The euphoniums or saxhorns, known as “harmonies”, are regularly used to replace the French horn, in disuse among most of the Purépecha bands today.

These groups are economically more active than all the other groups in the region, their income, according to field data from 1980 and 1981, oscillate between 10,000 and 60,000 Mexican pesos, so hiring a band at the party is in question. direct relationship with the economic possibilities of the organizers of the event or through a global cooperation between the inhabitants of a community.

Actually the costs are really fair, if you take into consideration the increased number of contract musicians who play for two or three days, with breaks only for eating and sleeping. It is also worth taking into account how difficult it is for some musicians to acquire the most expensive instruments in the festive environment, which are the metal-breath and wood-breath instruments, although some have been obtained second-hand or through family inheritance.

Above all, the presence of a band gives prestige and status to the Purépecha party. A relevant aspect of this are the skills of execution, direction, repertoire and popularity of the bands that play in their own towns or in others that they attend by commitment. The first part of the competitions is characterized by the interpretation of written music, based on the repertoire of waltzes, mazurkas, overtures and marches, in which the Purépecha musician demonstrates his reading ability. The second part of these meetings, allows to unleash the improvised sense of abajeños and sones that locate the town in its region, at this moment it is common to see the collective euphoria or climax of the party, either through the tap dance, the shout expressive or the traditional burning of castles and pyrotechnic bulls.

The last part of the competitions, generally alternated with that of abajeños and sones, also gives an opportunity to requests from cargueros and assisting people, from the commercial repertoire based on mambos, danzones, pasodobles, cumbias, etc., or from traditional pieces such as corridos in instrumental version and polkas.

Final Words

Registering the music in the Purépecha festival was not an easy task if we take into account that in each town there are at least two or more festivals with music. Those registered with recording material during January, February and March of 1981, almost all of them were for employers, there were also wedding and carnival events. In the last phase, visits were made to the communities to obtain complementary information on the musical genres present in the cycle of the Purépecha Festival, which we have been following since February 1980.

The commitment does not end here yet, as there were still many communities to visit and cover through sound recording in those festivities with movable dates such as Corpus Christi and its processions by guilds, which in some places become the most sumptuous event. We hope to have a new opportunity to complete the task begun in field recording and hopefully the musical selection made will show the particular meaning that the regional festival presents. In each one we find friends before whom the commitment is the achievement of this compilation.

In a special way we express our most sincere gratitude to all those people who offered us hospitality in their homes, to the musicians in whom we admire their effort to keep the tradition alive; Professor Francisco Elizalde García and his radio program “Mañanitas Purépechas” from XEZM (Zamora, Mich.) from whom we obtained the first approaches to the music of the region.

We also thank the Regional Delegation of the National Institute of Anthropology and History in Morelia, for their teacher Irene Vázquez Valle, head of collaboration; INAH Record Publishing Department, for their support and comments on the preparation of this volume, which aims to continue the study of Son in Mexico, widely referred to in the INAH Record Series and to Dr. Luis González y González, President of El Colegio de Michoacán, A. C., from whom we have always received the friendly word and the encouragement for the task already begun.

ARTURO CHAMORRO AND MARIA DEL CARMEN DIAZ DE CHAMORRO.

¹ Alberto Beltrán, “Introducción” al Calendario de Fiestas Tradicionales. México, S.E.P., Dirección General de Arte Popular, 1977, pp. 3-7.

² Celso Lara, “Aproximación científica al estudio del Folklore”, Folklore Americano. México, Instituto Panamericano de Geografía e Historia, O.E.A., 1976, Núm. 22, p. 54.

³ Héctor Martínez Arellano, “Vi0cos: las fiestas en la integración y la desintegración cultural”, Revista del Museo Nacional. Perú, 1956, T. XXVIII, p. 244.

⁴ Benedict Warren, La Conquista de Michoacán: 1521-1530, Morelia, Fimax Editores, 1977, p. XIII.

⁵ Francisco Miranda, “Estudio Preliminar” a La Relación de Michoacán. Morelia, Fimax Editores, 1980, pp. XXXII – XXXIV.

⁶ Agustín Jacinto Zavala, “La Visión del Mundo y de la Vida entre los Purépechas”, Ponencia presentada en el Segundo Coloquio de Antropología e Historia Regionales, Zamora, Michoacán.

⁷ Fray Jerónimo de Alcalá, La Relación de Michoacán, Morelia, Fimax Editores, Vol. V de la Colección de Estudios Michoacanos, 1980. El manuscrito original de esta obra procede del Siglo XVI y se conserva en la Real Biblioteca de San Lorenzo de El Escorial en España.

⁸ María Teresa Sepúlveda, Los Cargos Políticos y Religiosos en la Región de Pátzcuaro, México, Instituto Nacional de Antropología, SEP-INAH, Colección Científica No. 19, Etnología, 1974.

⁹ Daniel Castañeda, “Una flauta de la Cultura Tarasca”. Revista Musical Mexicana, México, Vol. 1. No. 5. Marzo 7, 1942, p. 109.

¹⁰ Op. Cit. p. 276.

¹¹ Fray Maturino de Gilberti, Diccionario de la Lengua Tarasca o de Michoacán, Guadalajara, Colección del Siglo XVI, Núm. 9, 1962.

¹² Relación de Michoacán, Op. cit. Tercera parte, p. 276.

¹³ Thomas Stanford, A linguistic analysis of music and dance terms from three sixteenth century dictionaries of mexican indian languages, Austin, University of Texas, Offprint Series No. 76, 1966, p. 106.

¹⁴ Robert Stevenson, Music in Aztec and Inca Territory, Berkeley, Calif., 1966, p. 172. Apud, Antonio de la Cibdad Real, Relación Breve y Verdadera, documentos inéditos para la Historia de España, LVII-LVIII (1872-1873).

¹⁵ Inspección Ocular en Michoacán, regiones centrales y sudoeste. México, Editorial Jus, Introducción y Notas de José Bravo Ugarte, 1960, p. 80 (Documentado en el Archivo General de la Nación. Ramo Historia. Tomo 73. Folios 285-405).

¹⁶ Thomas Stanford, “The Mexican Son”, Yearbook of the International Folk Music Council, Austin, Texas, 1972, p. 66 Apud, Diccionario de Autoridades de la Real Academia de la Lengua (1726-1739).

¹⁷ Gabriel Saldívar, Historia de la Música en México, México, S.E.P. 1934, pp. 221-223, 252-253.

¹⁸ Thomas Stanford, Op. cit., pp. 66-85.

¹⁹ Vicente T. Mendoza, Panorama de la música tradicional de México, México, U.N.A.M., Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, 1956, p. 59.

²⁰ Gerónimo Baquéiro Foster, Historia de la música en México, México, S.E.P.-I.N.B.A., Vol. III, 1964, pp. 14-15.

²¹ Irene Vázquez Valle, El son del sur de Jalisco, Guadalajara, Edición especial del Departamento de Bellas Artes y el Gobierno de Jalisco (Primera Parte), 1976.

²² Vicente T, Mendoza, Op. Cit., Gabriel Saldívar, Op. Cit., José Raúl Hellmer, “The music of the mestizo”, Toluca Gazette, Toluca, Junio 15, Modern Mexican Music, Part II, 1960, p.5.

²³ Mark Stephen Foguelquist, Rhytm and form in the contemporary son jalisciense, Los Angeles, Calif., U.C.L.A. Tesis, 1975, p. 7 y, Laurence Ira Saunders, The son huasteco, Los Angeles, Calif., U.C.L.A. Tesis, 1976, p. 33.

²⁴ Thomas Stanford; Op. Cit., p. 81.

²⁵ Salvador Próspero Román, “Origen de las Bandas y Orquestas Populares en Michoacán”, Kueraani, Morelia, Organi cana de Artistas y Escritores, 1972. ación Michoacana de Artistas y Escritores, 1972.

²⁶ Irene Vázquez Valle, Op. Cit., (Parte Segunda)

²⁷ Thomas Stanford, Op. cit., p. 77, los define como de “seis que alterna”.

²⁸ Pablo Velázquez Gallardo, Diccionario de la Lengua Phorhépecha, México, Fondo de Cultura Económica, Sección de Obras de Antropología, 1978, p. 218 refiere el vocablo uárhi como dama o mujer.

²⁹ Francisco Domínguez, Sones, canciones y corridos michoacanos, México, Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes, Talleres Gráficos de la Nación, 1941, Vol. 1, Delfino Gil Madrigal: comunicación verbal aludiendo a la música tocada por su padre, Delfino Madrigal en la Orquesta de Crispín Tinajero hacia principios de siglo.

³⁰ Por considerarse a la pirekua, como un género vocal de gran importancia para el conocimiento de la música purépecha, merecería un estudio especial. Entre las grabaciones de notable calidad y autenticidad referiremos las de Henrietta Yurchenco, The Real Mexico in Music and Song, New York, Nonesuch Records, por citar uno de los más antiguos registros de este género.

³¹ Pablo Velázquez, Op. Cit., p. 179, “popote de la planta de raíz del zacatón”.

³² Nazir A. Jairazbhoy, “The South Asian double-reed aerophone reconsidered”. Etnomusicology, Ann Arbor, Michigan, Vol. XXIV. No. 1, 1980, p. 147.

³³ Francisco J. Santamaría, Diccionario de mejicanismos, México, Editorial Porrúa, 2a. Edición, 1974, p. 678 “varas de membrillo”.

³⁴ Ibid., p. 429, “voz tarasca de la ciperácea”

³⁵ Arturo Warman, La danza de Moros y Cristianos, México, SEP-SETENTAS, No. 46, 1972, pp. 104-105.

³⁶ Carl Lumholtz, El México Desconocido, México, Editora Nacional, Tomo II, 2a. Edición, 1960, pp. 337-398.

³⁷ Comunicación del maestro Defino Gil Madrigal, organista en Morelia.

³⁸ Notas al disco Música de Cámara Kuerani, México, Secretaría de Educación Pública, Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo, 1980. Recopilación de Salvador Próspero Román.

³⁹ Robert Stevenson, Heterofonía, México, Revista Musical, No. 37, 1974.

⁴⁰ Mark Stephen Foguelquist, Op. Cit.

⁴¹ Stanley Brandes, “Dance as Metaphor: A case from Tzintzuntzan, México” Journal of Latin American Lore, Berkeley, Calif., 5/1, 1979, p. 29.

⁴² Nombres científicos tomados de Francisco J. Santamaría, Diccionario de Mexicanismos, México, Editorial Porrúa, 1974, pp. 38, 232, 852, 976, 994; 562, 854.

⁴³ Warman. Op. cit., p. 104.

⁴⁴ Salvador Próspero Román, Op. cit.

Face A

No.1

THE KUEREPO

abajeno

Registered during the festivities of the Lord of the Rescue in the town of Tzintzuntzan. Its execution corresponds to the burning of the pyrotechnic castle, at the moment in which the competition of the regional bands took place. From what the interpreters tell us, this abajeño seems to be by an anonymous author and its theme alludes to a certain type of fish also known as “charal pinto” that grows in Lake Pátzcuaro.

The execution of this abajeno denotes the classic style of the bands of the Sierra, through the Banda San Francisco de Cherán, composed of the following elements:

Melchor Pulido (conductor), tenor saxophone in Bb (B flat); Margarito Pahuamba, tenor saxophone in Bb; Antonio Tapia, tenor saxophone in Bb; Mario López, alto saxophone in Eb (E flat); Benedicto Huerta, alto saxophone in Eb; Salomón Olivares, soprano saxophone in Eb; Antonio Fabián, clarinet in Bb; Eustachian, clarinet in Bb; Eusebio González, clarinet in Bb; Ruperto de la Cruz, clarinet in Bb; Reynaldo López, rod trombone in C; Fermín Fabián, rod trombone in C; Nicolás Rodríguez, trumpet in Bb; Pablo Agustín, trumpet in Bb; Graciano, trumpet in b; Arnulfo Macías, alto saxhorn in Eb; Felipe Huerta, tuba or helicón in Bb; Francisco Macías, hype; Artemio Olivares, cymbals; Elias Hernandez, snare drum.

Recording date: February 24, 1981.

No. 2

TULE FLOWER AND FRIJOLITO FLOWER

sonecitos

Linked pieces that are played for the entrance of the Carnival dance known as chanantzkua, from the island population of Jarácuaro in Lake Pátzcuaro.

The accompanying group is that of the reed flute and drum led by Tata Pedro Patricio, a 74-year-old blind musician who began playing the flute at the age of 16, learning by oral tradition. Tata Pedro tells us that these sonecitos were part of the custom of the grandparents and were interpreted on festive occasions inside the uatapera at the time of the presentation and change of the “cargos”, so it is believed that they are authored. anonymous these little sonnets, according to the opinion of the musicians of the region.

The tendency to use the pentatonic scale (with five sounds) with deep Mesoamerican roots is recognized in these interpretations, although the Hispanic influence can be appreciated in the rhythmic structure and the use of the European drum.

Tata Julio Domínguez, director of the aforementioned dance, as well as the accompanying musicians of this group, are natives of Jarácuaro who, in addition to their festive activities, are dedicated to the work of the chuzpata, a type of palm that grows in the lake portion with which they They make hats, baskets and other handicrafts.

Performers: Pedro Patricio, reed flute; José Domínguez, tarolita.

Recording date: January 22, 1981.

No. 3

STEPPING ON CROOKED

abajeno

Composition by Tata Juan Crisóstomo, originally from Quinceo, member of his community orchestra, where the recording was made.

In this abajeño a different style can be appreciated from the other groups of the Sierra, conserving its combined rhythmic structure and the development of descending melodies that end in the classic cadence of the jarabe, although it could also be recognized in the finale, a certain influence of the Jalisco son, justified by the cultural exchange between Jalisco and Michoacán.

The author of this piece tells us that they usually play it at patron saint and wedding festivities. Its theme revolves around the following story provided by Tata Juan Crisóstomo himself: “At first the abajeño had no name and I asked one of my sons: let’s see my children, how do we name this abajeño? then one says: look how you step, for playing around you walk crookedly, you wear crooked heels. And that’s how the name stuck. It is also said that when someone gets drunk and goes to jail they already “stepped crookedly”. When a girl gets married and it goes badly in marriage, it is also said “he stepped on crooked”.

Performers of the Quinceo orchestra:

Francisco Salmerón Equihua (conductor), alto saxophone in Eb; Juan Crisóstomo Valdéz, first violin; Eleuterio Crisóstomo Carrión, plunger trombone in C; Cecilio Crisóstomo Carrión, four-string double bass; Miguel Corales Alonso, second violin; Daniel Flores Vargas, clarinet in Bb; Pedro Luna Flores, cello.

Recording date: March 2, 1981.

No. 4

CARNIVAL LITTLE BULL

son

Genre recorded in the Carnival festivities in Ocumicho, of which the musicians refer us is by an anonymous author. The characteristic of this “little bull” is that the band joins a walk during which the recording was made, in which they appreciate the different volumes of the instruments due to the dispersion of the performers. This type of piece is performed only during that time as it serves to accompany the presentation of bulls, of the freighters in turn and the choreography of the latter within the iuriso, where women and girls crash eggshells, full of confetti and dust. of golden color on the heads of the musicians and attendees.

The walk that proceeds to the cardboard bull is presented as an element of play and fun, in which men, women, adolescents and children participate.

Performers of the Band of San Pedro de Ocumicho:

Natividad Quiróz, clarinet in Bb; Federico Elías, clarinet in Bb; Rosalío Pascual, clarinet in Bb; Miguel Vicente, trumpet in Bb; Timoteo Vicente, rod trombone in C; Fernando Vicente, slide trombone in C; Narciso Cruz, piston trombone in C; Leobardo Vicente, tenor saxophone in Bb; Lorenzo Pascual, alto saxophone in Eb; Antonio Hernández, fun sex high on Eb; Zacarías Benito, helicon in Bb; José Luis Vicente, snare drum; Hector Aparicio, bass drum; Uriel Vicente, cymbals.

Recording date: March 2, 1981.

(Tuesday of Carnival)

No. 5

CURPITES DANCE

abajeno

Anonymous piece recorded during the Los Reyes festival contest in San Juan Nuevo Parangaricutiro. The dance is characterized by the improvisation of steps on a floor. It is made up of the following characters: the maringuia or lady, the tarepeti or old man and the curpites or young people.

The maringuia dances with the body almost immobile, raising the arms to the height of the head with slight inclinations, while the pics follow the rhythm of the abajeño with very small steps that stop, according to the cuts typical of the music. The tarepeti dances in a similar way but with his arms behind him and in one hand he carries a wooden stick, the steps are similar to those of the “lady”, with the freedom to improvise and marking the musical changes with a slight tapping.

It is common for abajeños and sones to be premiered for competitions, promoting a fresher and younger sense of dance, with a certain order in the repertoire, which is:

- regional son input

- syrup or abajeno

- regional son

- abajeno for curpites

- abajeño for the maringuia

- abajeño for the tarepeti

Apparently it is a courtship dance between young people, there is a custom that the curpites dance accompanied by the orchestra in front of their girlfriends’ house, later they, as a response and attention to the groom, have to attend the competition in absolute discretion.

Members of the Aranza orchestra:

Nicolás Rodriguez, trumpet in Bb; Juan Villanueva, alto saxophone in Eb; Ignacio Melchor, saxophone having in Bb; Abel Jiménez, trumpet in Bb; Antonio Macías, trumpet in Bb; Epitacio Equihua J., five-string vihuela, with four-string work.

Recording date: January 8, 1981.

No. 6

MOORS DANCE

sonecitos

Compiled in the town of Huáncito, in the Cañada de los Once Pueblos, on the occasion of the San Sebastián Patrono festivities. By oral source it is said that they are from an anonymous author and are characterized by their linked phrases, each corresponding to a choreographic movement.

The first part is made up of 6/8 and 3/4 rhythms and tends to be a bit more pronounced and cheerful, linked to a slow melodic movement without a defined beat in which the dancers clash the spurs of their boots (as can be heard in the example clearly), continuing towards a rapid movement, as a restatement of the initial sentence.

As is customary in other festive-religious dances, the Moorish dance takes a tour of the main houses of the town, especially in the patios of the houses of the cargo carriers and the priest.

Generally these little sonnets are accompanied by a band, although we remember that during the Colony they were accompanied by drums and shawms, as well as some trumpets.

Members of the Santa Cecilia Band from Ichán:

Felipe Pablos (conductor), slide trombone in Bb; Juan Alejo, rod trombone in C; Máximo Magaña, piston trombone in C; Leovigildo Bartolo, trumpet in Bb; Salvador Valdovinos, trumpet in C; Miguel Magaña, trumpet in Bb; Procopio Pablo, tenor saxophone in Bb; Rogelio Magaña, alto saxophone in Eb; Gabino Baltasar, clarinet in Bb; Abel García, clarinet in Bb; Dámaso Pablo, clarinet in Bb; Gilberto Gregorio, clarinet in Bb; Luis Morales Secundino, clarinet in Bb; Vidal Gregorio López, snare drum; Miguel Macial, bass drum; Herlindo Magaña, cymbals.

Recording date: January 20, 1981.

Face B

No. 1

TORITO FOR CASTLE

son

Old genre of anonymous author arranged by Argimiro Ascencio, Director of the Band “La Michoacana” from Ichán. Musicians usually play it during Carnival and also at weddings, although in this case it was performed on the occasion of the burning of a castle, and a little bull with pyrotechnic lights during the festivities of the Lord of the Rescue in Tzintzuntzan.

They also held a competition for regional bands on said festivity, in which priority was given to the repertoire with the greatest popular demand, such as the abajeños and toritos.

In this example, combined bars can be seen right at the entrance of the son, taking a 3/4 for the brass instruments and a 6/8 for the clarinet, and then continuing in the same six-eight rhythm, in which the skillful executions of the trumpets stand out towards the second part of the little bull.

The “La Michoacana” Band has acquired great fame for its quality of execution, the late Isaac López, notable trumpeter from Ichán, a place of great composers, is especially remembered.

Members of the Band “La Michoacana” from Ichán:

Argimiro Ascencio (conductor), trumpet in Bb; Rigoberto Zamora, helicon in C; Silverio Bartolo, trumpet in Bb; Alfonso Gregorio, trumpet in Bb; Gerardo Ramos, rod trombone in C; Antonio Ascencio, slide trombone in C; Eduardo Miguel, rod trombone in C; Alfredo Granados, clarinet in Bb; Abel Granados, clarinet in Bb; Gilberto Gregorio, clarinet in Bb; Herlindo Andrés, clarinet in Bb; Eustorgio Bartolo, tenor saxophone in Bb; Bernardino Francisco, alto saxophone in Eb; Julián Bartolo, alto saxophone in Eb; Simón Francisco, baritone saxhorn in Bb; Justo Gregorio, alto saxhorn in Eb; Enrique Uribe, alto saxhorn in Eb; Francisco Gregorio, cymbals; Antonio Fuentes, bass drum; Pedro Valencia, snare drum.

Recording date: February 24, 1981.

No. 2

K’AN P’IKUKUA (CUT THE LEAF OF THE CORN)

sonecito

The record comes from the mountain population of Cheranástico or Cherán Atzícurin, made in the house of Mr. Jesús Hérnandez Tziandón chirimitero, who translates the theme of this little sonnet as “cutting the leaf of the corn plant” that is played on the 15th of August for the feast of the Virgin of the Ascension.

In this little sonnet a tendency towards the rhythm of 3/8 can be seen, although with some impreciseness. It is accompanied by two shawms and a wide snare drum, provided with calfskin that is struck with sticks or wooden drumsticks. The optimal tuning of this drum is sought in the highest pitch, which is obtained by pulling ixtle ropes, placed in the body of the membranophone.

The shawm consists of 9 holes, which produce the sounds of the diatonic scale, depending on the pressure of the lips and the half covers with the fingers. The instrument, made of arbutus wood, was acquired in Ahuiran, and the mouthpiece is always made by the performer, his 10 and 15-year-old grandchildren accompany him.

Members:

Jesus Hernandez Tzianddon, chirimía first; Rodolfo Medina, second; Aniceto Hernandez, playground.

Date of recording: 1st. of March 1981.

No. 3

AT THE FOOT OF THE VOLCANO

abajeno

Inspiration by Miguel Sosa, recently composed for the dance of Viejitos recorded during the festivities of Santo Tomás de Aquino, in the mountain town of Cocucho.

This abajeño presents a notable influence of the syrup and even though it could be similar in its instrumental endowment to the mariachi, the musicians in particular make us distinguish that it is an “accompaniment orchestra” to the dance, since instead of the traditional guitarrón, it uses the double bass together with the band’s own instruments, such as saxophone, trumpet and trombone.

The rhythm section is characterized by a sequence of “triplets” in 6/8 time, closely related to the zapateado of the Viejitos. In this dance the typical style of the Sierra is appreciated, also associated with the other Oldies of Cherán, Tingambato, Uruapan and Tingüindín. The difference of this group, with the other dances of the lake towns of Jarácuaro and Santa Fé de la Laguna, lies in the organization of the choreography and the improvisation of movements, as well as the execution of abajeños that have very different rhythmic cuts.

The dance is of a humorous type, in which young people and mature men generally dress up, with wooden masks that represent the face of an old man, a hat decorated with ribbons, a woolen cotton shirt and white pants, sandals and a otate cane, with the one that supports and gives rhythmic accentuations.

Due to the composition of the clothing, music and instruments, the dance seems to be of European or mestizo origin, with the exception of the cane, whose use and design is believed to have a Mesoamerican origin.

The orchestra that accompanies this dance comes from Angahuan, reinforced by musicians from Corupo, and communities from the Paricutín volcanic region.

Members:

Isidro Soto, violin; Esteban Melgarejo, tenor saxophone in Bb; Guadalupe Rita, trumpet in Bb; Salvador Tadeo, trumpet in C; Dionisio Amado Lázaro, 4-string double bass; Miguel Sosa, trumpet in Bb; Josebio Soto, violin; José Isabel Bravo, sixth guitar; Florencio Cruz, 5-string vihuela.

Recording date: January 28, 1981.

No. 4

T’IPICHUKUA URAPITA (WHITE SHORTS)

regional son

They are regional from the Sierra, composed 25 years ago by Francisco Salmerón Equihua, director of the Quinceo orchestra, the town where the recording was made.

This son is usually played for weddings, parties and Corpus Christi. In its rhythmic structure, the use of 3/8 prevails through certain figures given by the piston trombone, which gives the orchestra its own style.

The author of the son translates the theme as “white pants” alluding to the fact that many years ago the men of the mountains wore white pants.

It is important to mention the variety of bow instruments endowment; Thanks to the family tradition and the personal enthusiasm of those who make up the orchestra, its disappearance has been avoided.

Members of the Quinceo orchestra:

Francisco Salmerón Equihua, alto saxophone in Eb; Juan Crisóstomo Valdéz, first violin; Eleuterio Crisóstomo Carriún, piston trombone in C; Cecilio Crisóstomo Carrión, 4-string double bass; Miguel Corales Alonso, second violin; Daniel Flores Vargas, clarinet in Bb; Pedro Luna Flores, cello.

Recording date: March 2, 1981.

No. 5

THE CROSS

sonecito

Selection by an anonymous author that is part of the dance of Santiagos, recorded in Erongarícuaro, a town on the banks of Lake Pátzcuaro, on the occasion of the festivities of El Señor de la Misericordia.

The accompaniment of this sonecito in rhythm of 2/4 is done with the endowment of the mariachi without trumpet or “mariachito”.

The Santiagos dance for this event was reinforced by another equal one from Pátzcuaro. It originally consists of 25 little sonnets, whose names are derived from choreographic movements such as: the cross, the entrance to the town, the presentation, the comb, the followed, the greeting, the snail, the machetes, the bow, the polka, the uprising of rows, the pigeon, the snake, the “O”, the basket, the fight, the lasso, the story, the performance, the goodbye and others.

Due to its historical background, it seems to be closely related to the theme of the Moorish dance, although its characters vary a bit, as well as its instrumental accompaniment. The main character is Santiago Apóstol, represented by the director of the dance, dressed in a Spanish costume, with a machete and a wooden horse attached to his waist. This character is in constant motion. Both for the presentation of the characters, as well as for the choreography and musicalization, the representation seems to be related to the Dance of the Lord of the Rescue of Tzintzuntzan.

Members:

Alfredo Chávez, five-string vihuela; Pablo Jacobo, first violin; Jesús Chávez, second violin; Jesús Solorio, six-string guitarrón; José Meza, sixth guitar; Alfredo Vallejo, sixth guitar.

Recording date: January 6, 1981.

No. 6

ELVIRITA

abajeno

Composition by Agapito Secundino Faustino, recorded during the celebration of a marriage in the town of San Jerónimo Purenchecuaro, on the shores of Lake Pátzcuaro.