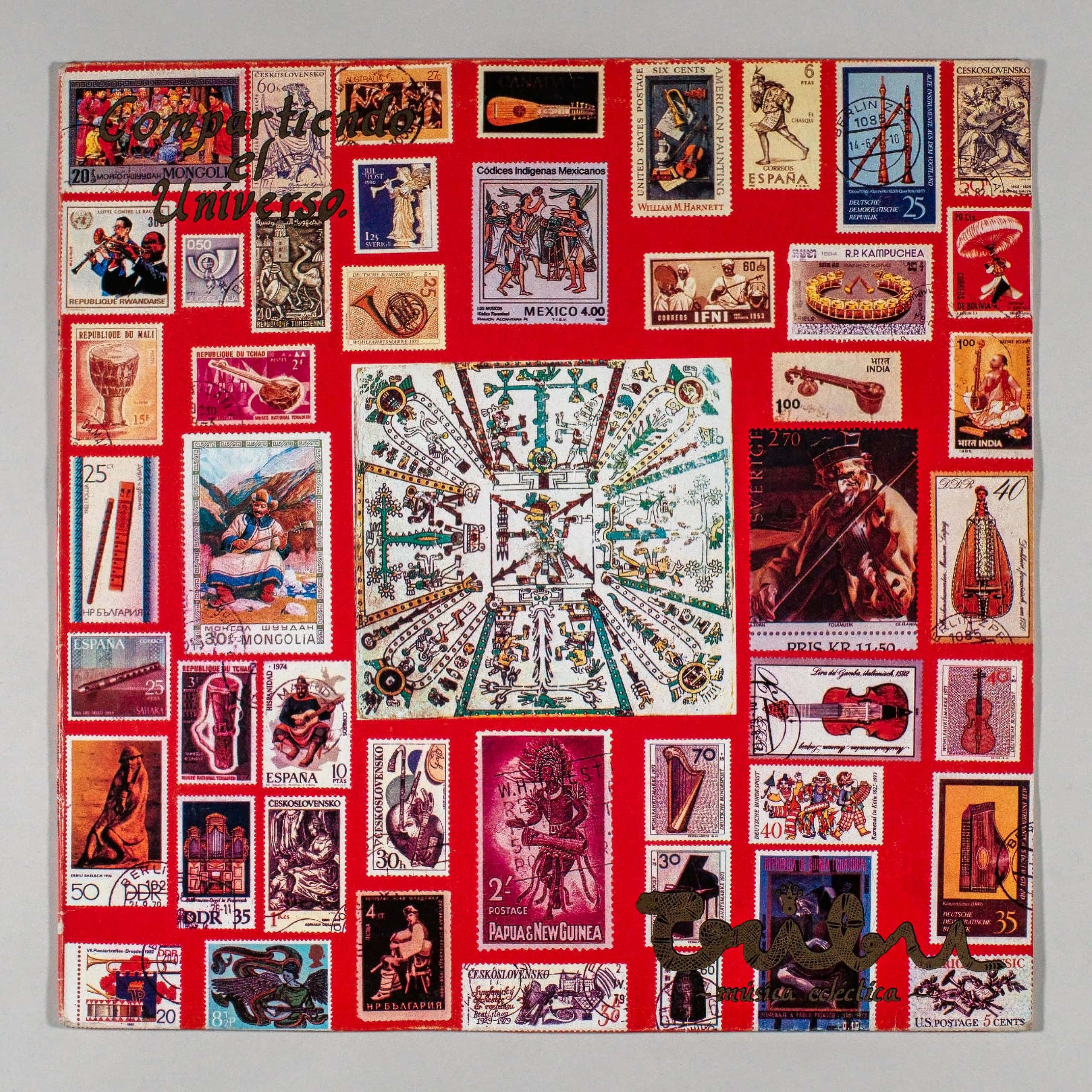

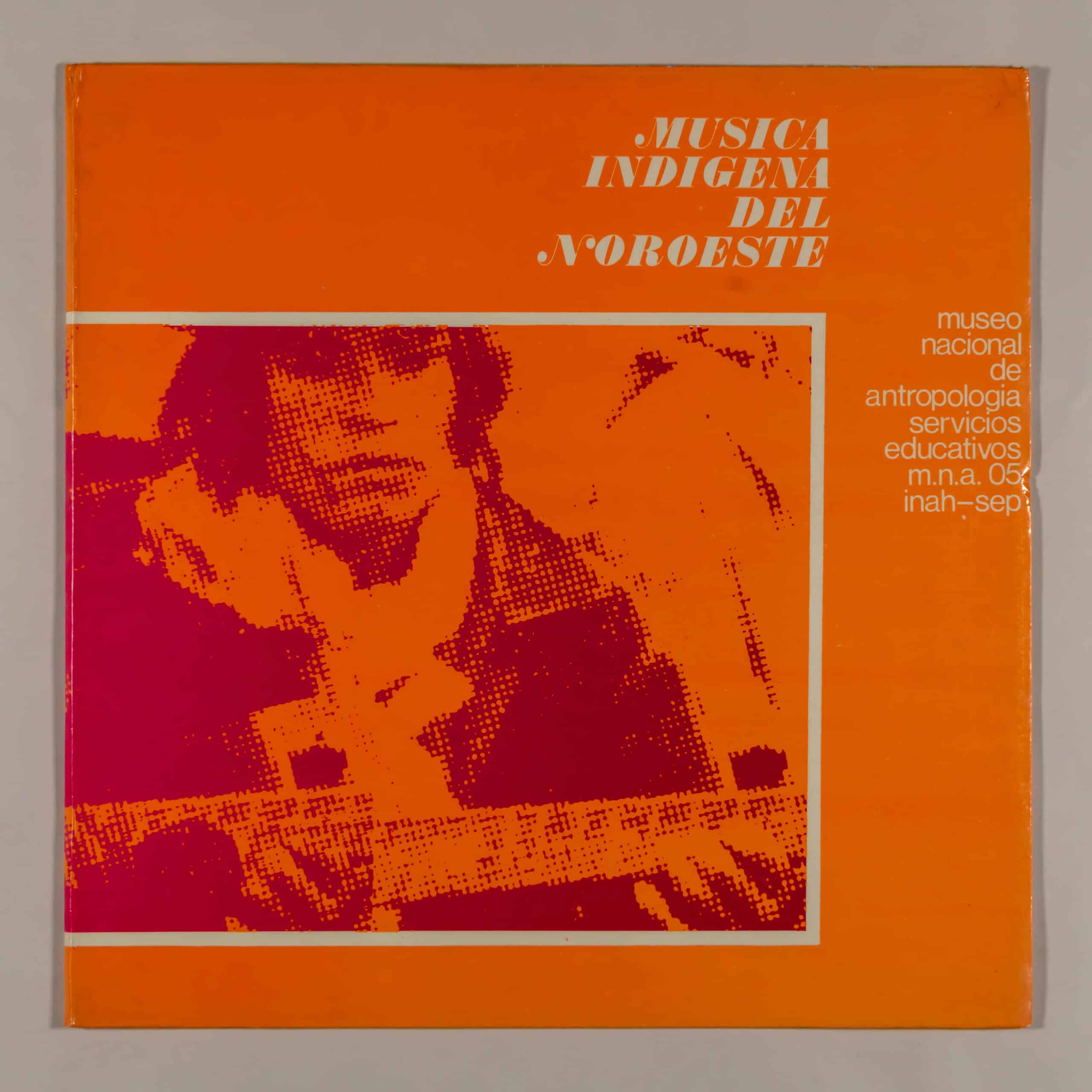

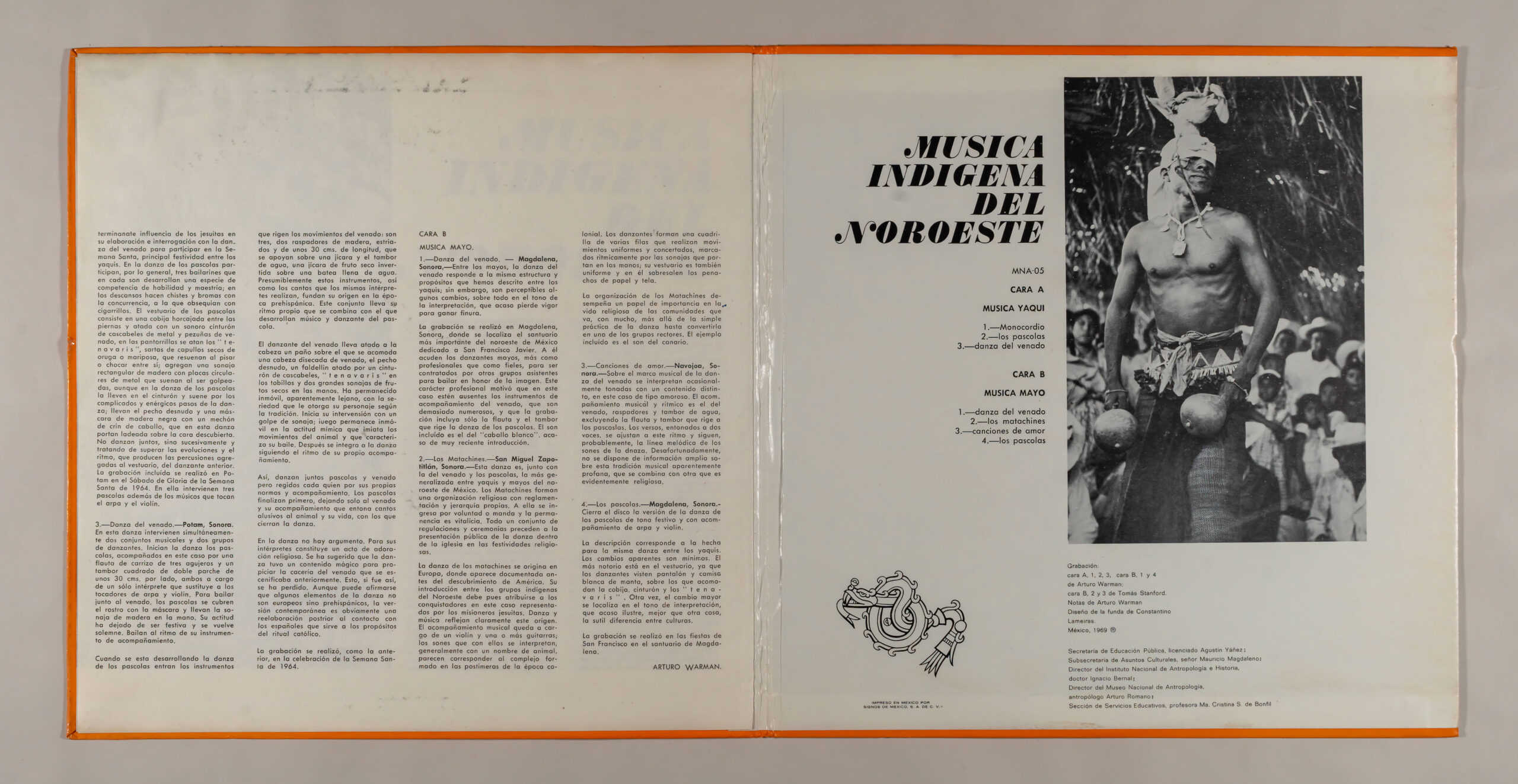

NORTHWEST INDIGENOUS MUSIC

INAH SEP

|

Label: INAH-SEP MNA-05 Released: 1969 |

Country: Mexico |

Info:

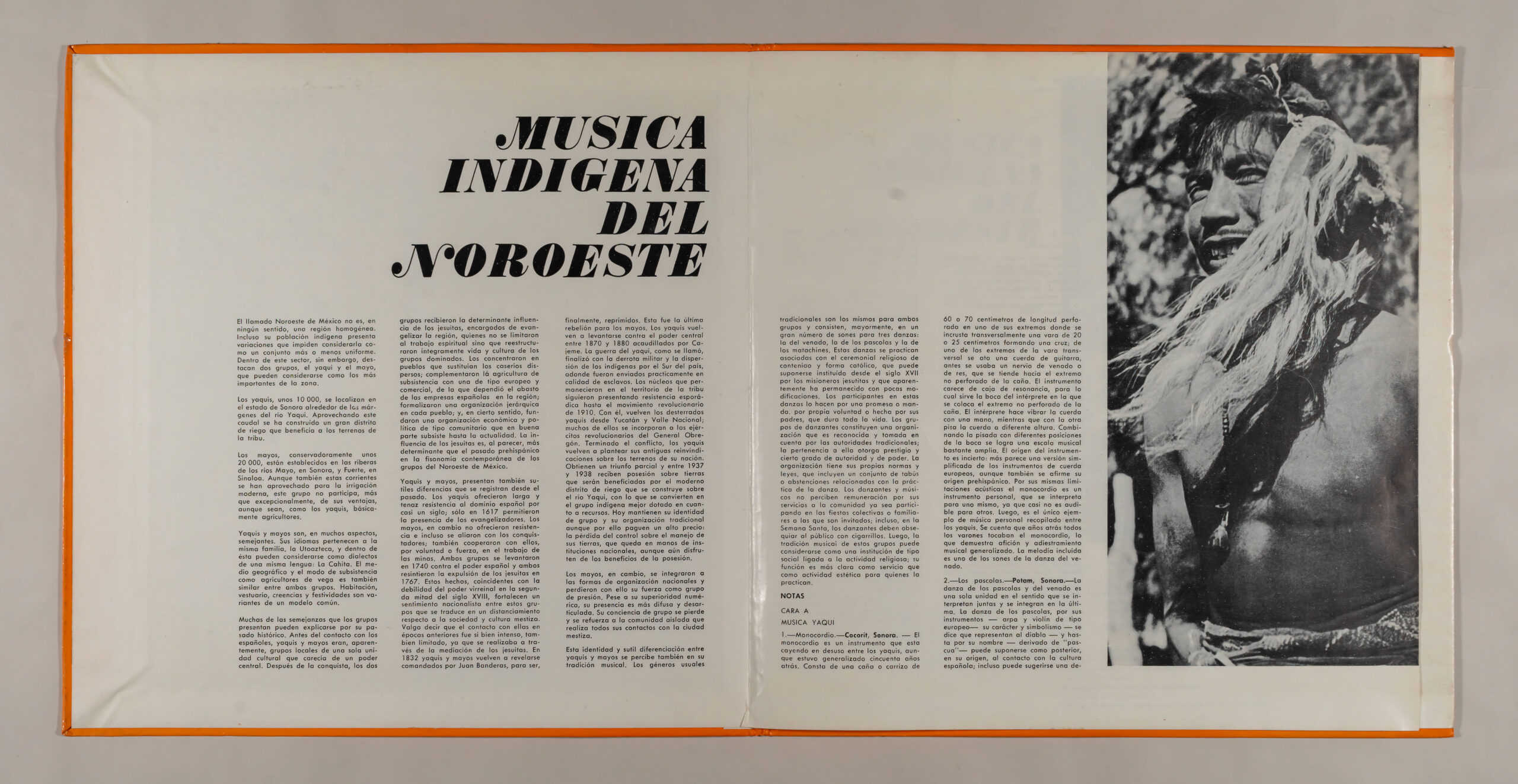

NORTHWEST INDIGENOUS MUSIC

The so-called Northwest of Mexico is not, in any sense, a homogeneous region. Even its indigenous population presents variations that prevent it from being considered as a more or less uniform group. Within this sector, however, two groups stand out, the Yaqui and the Mayo, which can be considered the most important in the area.

The Yaquis, about 10,000, are located in the state of Sonora around the banks of the Yaqui River. Taking advantage of this flow, a large irrigation district has been built that benefits the tribe’s land.

The Mayos, conservatively about 20,000, are established on the banks of the rivers Mayo, in Sonora, and Fuerte, in Sinaloa. Although these currents have also been used for modern irrigation, this group does not participate, more than exceptionally, in its advantages, even though they are, like the Yaquis, basically farmers.

Yaquis and Mayos are, in many respects, alike. Their languages belong to the same family, the Utoazteca, and within this they can be considered as dialects of the same language: La Cahita. The geographical environment and the mode of subsistence is also similar between both groups as farmers of the fertile plain. Room, clothing, beliefs and festivities are variants of a common model.

Many of the similarities that the groups present can be explained by their historical past. Before contact with the Spanish, Yaquis and Mayos were apparently local groups of a single cultural unit that lacked a central power. After the conquest, the two groups received the determining influence of the Jesuits, in charge of evangelizing the region, who did not limit themselves to spiritual work, but who completely restructured the life and culture of the dominated groups. They concentrated them in towns that replaced the scattered hamlets; they complemented subsistence agriculture with a European and commercial type, on which the supply of Spanish companies in the region depended; they formalized a hierarchical organization in each town; and, in a sense, they founded a community-type economic and political organization that largely survives to this day. The influence of the Jesuits is, it seems, more decisive than the pre-Hispanic past in the contemporary physiognomy of the groups of the Northwest of Mexico.

Yaquis and Mayos also present subtle differences that have been recorded since the past. The Yaquis offered long and tenacious resistance to Spanish rule for almost a century; only in 1617 did they allow the presence of the evangelizers. The Mayos, on the other hand, offered no resistance and even allied themselves with the conquerors; they also cooperated with them, by will or force, in the work of the mines. Both groups rose up in 1740 against the Spanish power and both resented the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1767. These events, coinciding with the weakness of the viceregal power in the second half of the 18th century, strengthened a nationalist sentiment among these groups that translated into a distancing from mestizo society and culture. It is worth saying that the contact with them in previous times was, although intense, also limited, since it was carried out through the mediation of the Jesuits. In 1832 Yaquis and Mayos rebelled again, commanded by Juan Banderas, to finally be repressed. This was the last rebellion for the Mayos. The Yaquis rise again against the central power between 1870 and 1880 led by Cajeme. The Yaqui War, as it was called, ended with the military defeat and the dispersion of the indigenous people in the south of the country, where they were sent practically as slaves. The nuclei that remained in the territory of the tribe continued to present sporadic resistance until the revolutionary movement of 1910. With it, the exiled Yaquis returned from Yucatán and Valle Nacional; many of them join the revolutionary armies of General Obregón. After the conflict, the Yaquis once again raised their old claims on the lands of their nation. They obtain a partial victory and between 1937 and 1938 they receive possession of lands that will be benefited by the modern irrigation district that is built on the Yaqui River, with which they become the best endowed indigenous group in terms of resources. Today they maintain their group identity and their traditional organization even though they pay a high price for it: the loss of control over the management of their land, which remains in the hands of national institutions, even though they still enjoy the benefits of possession.

The Mayos, on the other hand, were integrated into national forms of organization and thereby lost their strength as a pressure group. Despite their numerical superiority, their presence is more diffuse and disjointed. Their group consciousness is lost and the isolated community that makes all its contacts with the mestizo city is reinforced.

This identity and subtle differentiation between Yaquis and Mayos is also perceived in their musical tradition. The usual traditional genres are the same for both groups and consist, for the most part, of a large number of sons for three dances: that of the deer, that of the pascolas, and that of the matachines. These dances are practiced associated with the religious ceremonial of Catholic content and form, which can be assumed to have been instituted since the 17th century by the Jesuit missionaries and which has apparently remained with few modifications. The participants in these dances do it for a promise or mandate, of their own free will or made by their parents, which lasts a lifetime. The groups of dancers constitute an organization that is recognized and taken into account by the traditional authorities; belonging to it confers prestige and a certain degree of authority and power. The organization has its own rules and laws, which include a set of taboos or abstentions related to the practice of dance. Dancers and musicians do not receive remuneration for their services to the community, whether participating in collective or family parties to which they are invited; Even during Holy Week, the dancers must give the public cigarettes. Then, the musical tradition of these groups can be considered as a social institution linked to religious activity; its function is clearer as a service than as an aesthetic activity for those who practice it.

NOTES

SIDE A

YAQUI MUSIC

1.–Monochord.–Cocorit, Sonora.– The monochord is an instrument that is falling into disuse among the Yaquis, although it was widespread fifty years ago. It consists of a cane or reed 60 or 70 centimeters long, perforated at one end where a 20 or 25-centimeter rod is embedded crosswise, forming a cross; A guitar string is tied to one of the ends of the trans rod, before a deer or beef nerve was used, which is tended towards the non-perforated end of the reed. The instrument lacks a sounding board, for which the performer’s mouth is used, in which the non-perforated end of the reed is placed. The performer vibrates the string with one hand, while with the other he steps on the string at a different height. Combining the tread with different positions of the mouth, a fairly wide musical scale is achieved. The origin of the instrument is uncertain: it seems more like a simplified version of European string instruments, although its pre-Hispanic origin is also affirmed. Due to its acoustic limitations, the monochord is a personal instrument, which is interpreted for oneself, it is hardly audible to others. Then, it is the only example of personal music compiled among the Yaquis. It is said that years ago all the men played the monochord, which shows a general interest and musical training. The melody included is one of the sounds of the deer dance.

2.–Los pascolas.–Potam, Sonora.– The dance of the pascolas and the deer is a single unit in the sense that they are performed together and are integrated into the latter. The dance of the pascolas, due to its European-type harp and violin instruments, its character and symbolism – it is said that they represent the devil and even because of its name derived from “Easter” it can be assumed that it originated after contact with the culture Spanish; You can even suggest one of Terminate influence of the Jesuits in its elaboration and interrogation with the dance of the deer to participate in Holy Week, the main festivity among the Yaquis. In the dance of the pascolas, three dancers generally participate, who in each son develop a kind of competition and mark me with skill and mastery; in the breaks they make jokes and jokes with the audience, which they give away with cigarettes. The clothing of the pascolas consists of a blanket straddling the legs and tied with a sonorous belt of metal bells and deer hooves, on the calves the “tenavaris” are tied, strings of dried caterpillar or butterfly cocoons, which resonate when step on or bump into each other; they add a rectangular wooden rattle with circular metal plates that make a sound when struck, although in the pascola dance they wear it on their belt and it sounds because of the complicated and energetic steps of the dance; They are bare-chested and wear a black wooden mask with a lock of horsehair, which they wear tilted over their uncovered face in this dance. They do not dance together, but successively and trying to overcome the evolutions and rhythm produced by the percussion added to the costumes of the previous dancer. The included recording was made in Potam on Glory Saturday of Holy Week in 1964. Three pascolas take part in it in addition to the musicians who play the harp and the violin.

3.–Dance of the deer.–Potam, Sonora.– Two musical ensembles and two groups of dancers take part simultaneously in this dance. The pascolas begin the dance, accompanied in this case by a reed flute with three holes and a double-headed square drum of about 30 cm on each side, both performed by a single performer who replaces the harp and violin players. To dance alongside the deer, the pascolas cover their faces with the mask and carry the wooden rattle in their hands. His attitude has ceased to be festive and becomes solemn. They dance to the rhythm of their accompanying instrument.

When the pascola dance is taking place, the instruments that govern the movements of the deer enter: there are three, two wooden scrapers, fluted and about 30 cm long, which rest on a jícara and the water drum, a jícara of dried fruit inverted on a tray full of water. Presumably these instruments, as well as the songs that the performers themselves perform, found their origin in pre-Hispanic times. This group has its own rhythm that is combined with that developed by the pascola musician and dancer.

The deer dancer wears a cloth tied to his head on which a stuffed deer head is placed, his chest is bare, a short skirt tied by a belt of bells, “tena varis” on his ankles and two large rattles of dried fruit on the hands. He has remained motionless, apparently distant, with the seriousness that his character gives him according to tradition. He initiates his intervention with a rattle blow; then he remains motionless in the mimic attitude that imitates the movements of the animal and that characterizes his dance. Then the dance is integrated following the rhythm of his own accompaniment.

Thus, pascolas and deer dance together but each one is governed by their own rules and accompaniment. The pascolas finish first, leaving only the deer and its accompaniment that sings songs alluding to the animal and its life, with which they close the dance.

In dance there is no argument. For its interpreters it constitutes an act of religious worship. It has been suggested that the dance had a magical content to propitiate the deer hunt that was previously staged. This, if so, has been lost. Although it can be argued that some elements of the dance are not European but pre-Hispanic, the contemporary version is obviously a post-Spanish reworking that serves the purposes of Catholic ritual.

The recording was made, like the previous one, in the celebration of Holy Week in 1964.

SIDE B

MAYO MUSIC.

1.–Dance of the deer.–Magdalena, Sonora.– Among the Mayos, the dance of the deer responds to the same structure and purposes that we have described among the Yaquis; however, some perceptible changes, especially the tone of the interpretation, which perhaps loses vigor to gain finesse.

The recording was made in Magdalena, Sonora, where the most important sanctuary in northwestern Mexico dedicated to San Francisco Javier is located. The Mayo dancers come to him, more as professionals than as faithful, to be hired by other groups to dance in honor of the image. This professional character motivated that in this case the accompanying instruments of the deer are absent, which are too numerous, and that the recording includes only the flute and the drum that governs the dance of the pascolas. The son included is that of the “white horse”, perhaps of very recent introduction.

2.–Los Matachines.–San Miguel Zapotitlán, Sonora.– This dance is, along with the deer and the pascolas, the most widespread among Yaquis and Mayos in northwestern Mexico. The Matachines form a religious organization with its own regulations and hierarchy. It is entered by will or mandate and permanence is for life. A whole set of regulations and ceremonies precede the public presentation of the dance inside the church on religious festivities.

The dance of the matachines originates in Europe, where it appears documented before the discovery of America. Its introduction among the indigenous groups of the Northwest must therefore be attributed to the conquerors, in this case represented by the Jesuit missionaries. Dance and music clearly reflect this origin. The musical accompaniment is in charge of a violin and one or more guitars; the sounds that are interpreted with them, generally with the name of an animal, seem to correspond to the complex formed at the end of the colonial era. The dancers form a gang of several rows that perform uniform and concerted movements, rhythmically marked by the rattles they carry in their hands; His clothing is also uniform and in it the plumes of paper and cloth stand out.

The Matachines organization plays an important role in the religious life of the communities that goes far beyond the simple practice of dance to make it one of the governing groups. The included example is the son of the canary.

3.–Love songs.–Navojoa, Sonara.– On the musical background of the deer dance, tunes with a different content are occasionally interpreted, in this case of a love type. The musical and rhythmic accompaniment is that of the deer, scrapers and water drum, excluding the flute and drum that governs the pascoslas. The verses, intoned by two voices, adjust to this rhythm and probably follow the melodic line of the dance sounds. Unfortunately, extensive information is not available on this apparently secular musical tradition, which is combined with another that is obviously religious.

4.–Los pascolas.–Magdalena, Sonora.– The album closes with a festive version of the pascolas dance accompanied by harp and violin.

The description corresponds to that made for the same dance among the Yaquis. Apparent changes are minimal. The most notorious is in the costumes, since the dancers wear trousers and a white blanket shirt, on which they place the blanket, belt and “tenavaris”. Once again, the biggest change is located in the tone of interpretation, which perhaps illustrates, better than anything else, the subtle difference between cultures.

The recording was made at the San Francisco festivities in the Magdalena sanctuary.

ARTHUR WARMAN.

NORTHWEST INDIGENOUS MUSIC

MNA-05

SIDE A

YAQUI MUSIC

1.–monochord

2.–the pascolas

3.–deer dance

SIDE B

MAYO MUSIC

1.– deer dance

2.–the matachines

3.–love songs

4.–the pascolas

Recording:

side A, 1, 2, 3, side B, 1 and 4

by Arthur Warman;

side B, 2 and 3 by Tomás Stanford.

Notes by Arthur Warman

Constantine sleeve design

You lick.

Mexico, 1969 Ⓡ

Secretary of Public Education, Mr. Agustín Yáñez:

Undersecretary for Cultural Affairs, Mr. Mauricio Magdaleno;

Director of the National Institute of Anthropology and History,

Dr. Ignacio Bernal;

Director of the National Museum of Anthropology,

anthropologist Arturo Romano;

Educational Services Section, Professor Ma. Cristina S. de Bonfil.

PRINTED IN MEXICO BY

SIGNS OF MEXICO, S.A. DE C.V.

Tracklist:

NORTHWEST INDIGENOUS MUSIC

SIDE 1

- A1 Mákuli San Juan.–San Juan Chamula (Tzotzil).

Performers: ? - A2 Music for the Dance of the Negroes.–Aguacatenango (Itzeltal).

Performers: Andrés Hernández Pérez, reed flute; Silvestre Hernández Pérez, big drum; Antonio Rodríguez Hernández, small drummer. - A3 La Maruchita.–Venustiano Carranza.

Performers: Marimba “El Águila” by the Santiago brothers. - A4 San Mateo.–San Juan Chamula (Tzotzil).

Performers: ? - A5 Whistle And Bugle Music.–Tenejapa (Tzotzil).

Performers: Miguel Guzmán Tzurin, flute and cornet; Alfonso Guzman Tzurin, drummer. - A6 Zapateado Of Father Ruben.–Venustiano Carranza.

Performers: Marimba by José Leopoldo Villafuerte and sons.

SIDE 2

- B1 The Memelel.–Venustiano Carranza.

Performers: Miguel Guillén, guitar and singing; Maria Guillen, marimba. - B2 They are from the Royal Mayordomo.–Tenejapa (Tzotzil).

Performers: ? - B3 Music Of The Singles.–Colonia Veracruz, Margaritas (Tojolabal).

Performers: Manuel Pérez, mouth organ. - B4 Road to San Cristobal.–San Cristobal de Las Casas.

Performers: Marimba from Belisario Domínguez Boarding School. - B5 Procession Music.–Colonia Veracruz, Margaritas (Tojolabal).

Performers: ? - B6 El Bolonchón.–San Juan Chamula (Tzotziles).

Performers: ?

Credits:

Field recordings by Tomás Stanford and Irene and Arturo Warman.

Notes by Arthur Warman.

Cover design by Constantino Lameiras.

The recording was made at the San Francisco festivities in the Magdalena sanctuary.

Arturo Warman: Engraver, Adjunct Material Writer

Thomas Standford: Engraver

Victor Acevedo Martínez: Editor

Martín Audelo Chícharo: Editor

Guadalupe Loyola Zárate: Editor

Benjamín Muratalla: Editor, Director

Irene Vázquez Valle: Editor

H. Alejandro Castellanos Garrido: Editor, Researcher

Gabriela González Sánchez: Editor

Jazmín Rangel Evaristo: Editor

Guillermo Pous Navarro

Hugo De la Rosa Barajas

Alfredo Huertero Casarrubias: Illustrator

Guillermo Santana Ramírez: Designer

MUSICA INDIGENA DEL NOROESTE MUSICA YAQUI LP RECORD VINYL NEAR MINT

MUSICA INDIGENA DEL NOROESTE MUSICA YAQUI LP RECORD VINYL NEAR MINT