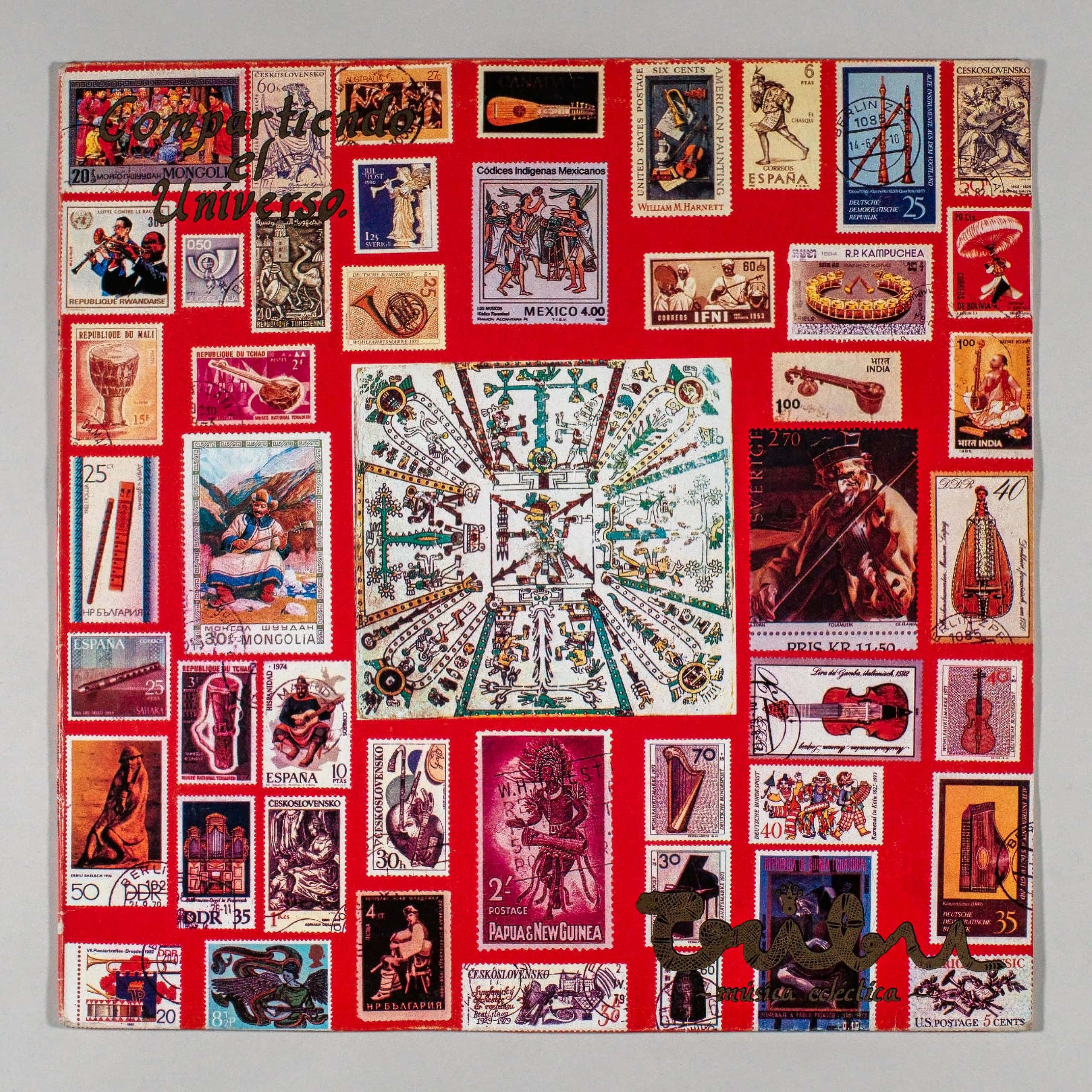

MUSIC OF THE HUAVES OR MAREÑOS

INAH SEP

|

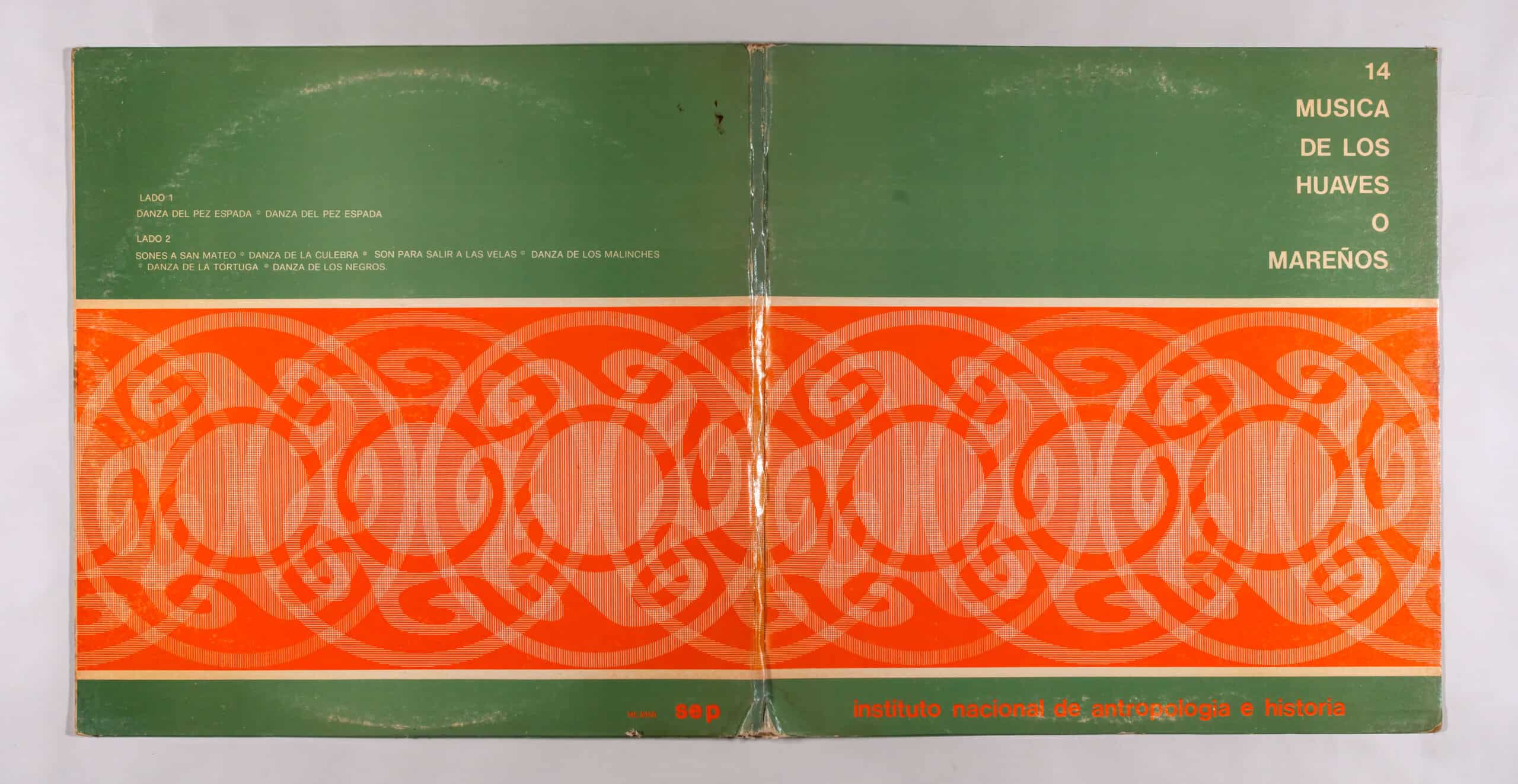

Label: INAH-SEP INAH-14, MC-0456 Released: 1974 |

Country: Mexico Genre: Sound |

Info:

14 MUSIC OF THE HUAVES OR MAREÑOS

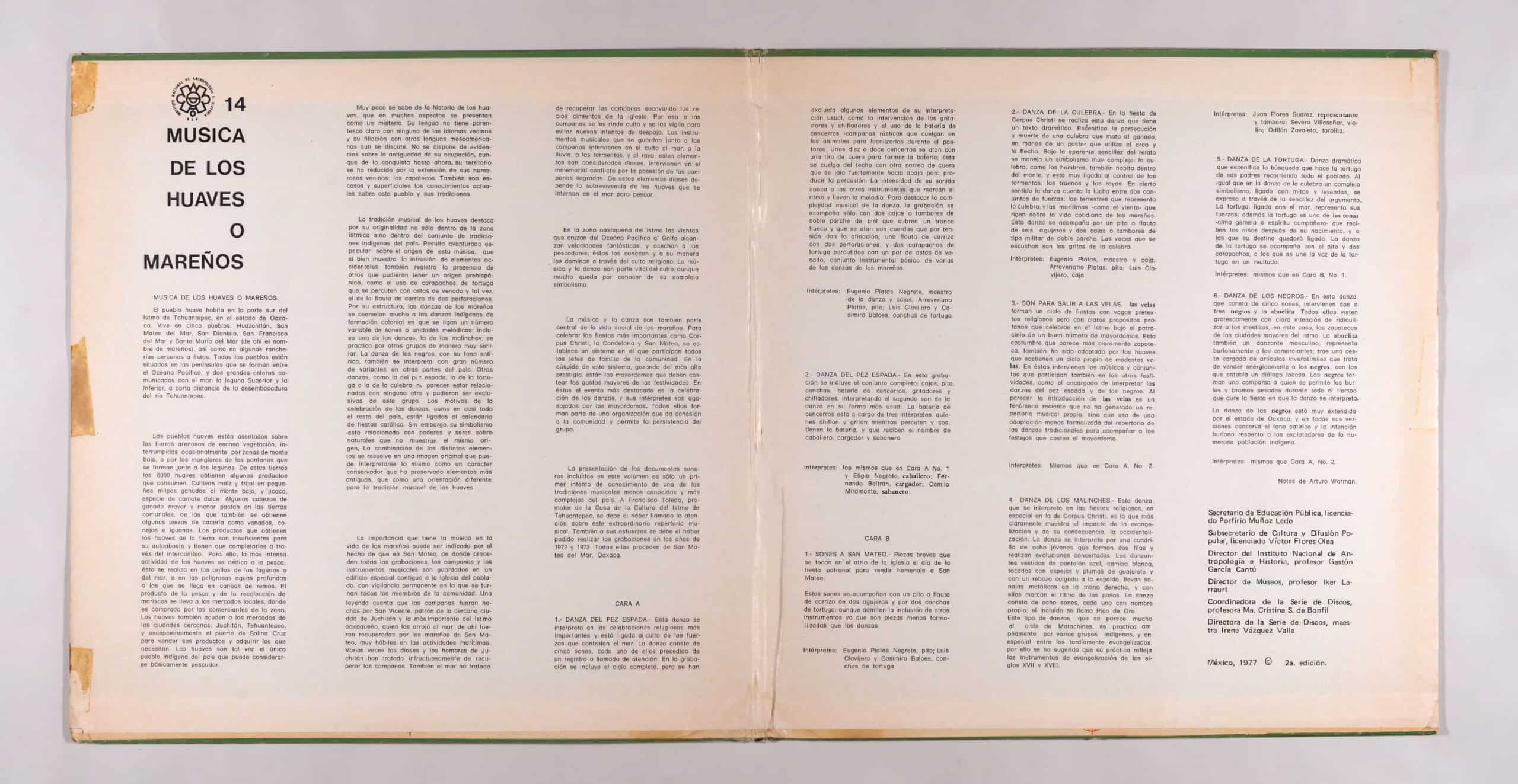

MUSIC OF THE HUAVES OR MAREÑOS

The Huave people live in the southern part of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, in the state of Oaxaca. He lives in five towns: Huazontlán, San Mateo del Mar, San Dionisio, San Francisco del Mar and Santa María del Mar (hence the name Mareños), as well as in some nearby ranches. All the towns are located on the peninsulas that form between the Pacific Ocean and two large estuaries connected to the sea: the Upper and Lower lagoons, a short distance from the mouth of the Tehuantepec River.

The Huave peoples are settled on sandy lands with little vegetation, occasionally interrupted by areas of scrubland, or by the mangroves of the swamps that form next to the lagoons. From these lands, the 8,000 Huaves obtain some products that they consume. They cultivate corn, beans in small cornfields reclaimed from the scrubland, and jicaco, a kind of sweet potato. Some heads of large and small cattle graze on communal lands, from which some game such as deer, rabbits and iguanas are also obtained. The products that the Huaves obtain from the land are insufficient for their self-sufficiency and they have to complete them through exchange. For this, the most intense activity of the Huaves is dedicated to fishing; This is done on the shores of the lagoons or the sea, or in the dangerous deep waters that are reached by rowing canoes. The product of fishing and shellfish harvesting is taken to local markets, where it is bought by local merchants. The Huaves also go to the markets of the nearby cities: Juchitón. Tehuantepec, and exceptionally the port of Salina Cruz to sell their products and acquire what they need. The Huaves are perhaps the only indigenous people in the country that can basically be considered fishermen.

Very little is known about the history of the Huaves, who in many aspects are presented as a mystery. Their language is not clearly related to any of the neighboring languages and their affiliation with other Mesoamerican languages is still disputed. There is no evidence about the age of its occupation, although from the conquest until now, its territory has been reduced by the extension of its numerous neighbors: the Zapotecs. Current knowledge about this town and its traditions is also scarce and superficial.

The musical tradition of the Huaves stands out for its originality not only within the isthmic zone but also within the set of indigenous traditions of the country. It is risky to speculate about the origin of this music, which, although it shows the intrusion of Western elements, also records the presence of others that could have a pre-Hispanic origin, such as the use of turtle shells beaten with deer antlers and perhaps , that of the reed flute with two perforations. Due to its structure, the dances of the Mareños are very similar to the indigenous dances of colonial formation in which a variable number of sones or melodic units are linked; even one of the dances, that of the malinches, is practiced by other groups in a very similar way. The black dance, with its satirical tone, is also performed in a number of variations in other parts of the country. Other dances, such as the swordfish, the turtle or the snake, do not seem to be related to any other and could be exclusive to this group. The reasons for the celebration of the dances, as in almost the rest of the country, are linked to the calendar of Catholic festivities. However, its symbolism is related to powers and supernatural beings that do not show the same origin. The combination of the different elements is resolved in an original image that can be interpreted both as a conservative character that has preserved older elements, and as a different orientation for the musical tradition of the Huaves.

The importance of music in the life of the Mareños can be indicated by the fact that in San Mateo, where all the recordings come from, the bells and musical instruments are kept in a special building next to the town church, with permanent surveillance in which all the members of the community take turns. A legend tells that the bells were made by San Vicente, patron of the nearby city of Juchitán and the most important of the Oaxacan Isthmus, who threw them into the sea; from there they were recovered by the people from San Mateo, very skilled in maritime activities. Several times the gods and men of Juchitán have tried unsuccessfully to recover the bells. The sea has also tried to recover the bells by undermining the strong foundations of the church, which is why the bells are worshiped and monitored to prevent further attempts at dispossession. The musical instruments that are kept next to the bells intervene in the cult of the sea, the rain, the storms, and the lightning; these elements are considered gods, they intervene in the immemorial conflict for the possession of the sacred bells. The survival of the Huaves who go into the sea to fish depends on these god-elements.

In the Oaxacan area of the isthmus, the winds that cross from the Pacific Ocean to the Gulf reach fantastic speeds, and lie in wait for the fishermen; they know them and in their own way dominate them through religious worship.

Music and dance are a vital part of the cult, although much remains to be learned about their complex symbolism. Music and dance are also a central part of the social life of the Mareños. To celebrate the most important festivals such as Corpus Christi, Candelaria and San Mateo, a system is established in which all the heads of families in the community participate. At the top of this system, enjoying the highest prestige, are the butlers who must bear the major expenses of the festivities. In these the most outstanding event is the celebration of the dances, and their interpreters are entertained by the butlers. All of them are part of an organization that gives cohesion to the community and allows the persistence of the group.

The presentation of the sound documents included in this volume is only a first attempt to learn about one of the least known and most complex musical traditions in the country. Francisco Toledo, promoter of the House of Culture of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, is responsible for drawing attention to this extraordinary musical repertoire. It is also due to his efforts that he was able to make the recordings in 1972 and 1973. All of them come from San Mateo del Mar, Oaxaca.

FACE A

1.- SWORDFISH DANCE.- This dance is performed in the most important religious celebrations and is linked to the cult of the forces that control the sea. The dance consists of five sounds, each of them preceded by a register or attention call. The recording includes the complete cycle, but some elements of its usual interpretation have been excluded, such as the intervention of the shouters and whistlers and the use of the battery of cowbells – rustic bells that hang on the animals to locate them during grazing. . About ten or twelve cowbells are tied with a leather strip to form the battery; this is hung from the ceiling with another leather strap that is pulled down hard to produce percussion. The intensity of its sound overshadows the other instruments that mark the rhythm and carry the melody. To highlight the musical complexity of the dance, the recording is accompanied only by two boxes or drums with double skin heads that cover a hollow trunk and that are tied with strings that, by tension, give the tuning; a reed flute with two perforations, and two tortoiseshells percussed with a pair of deer antlers, a basic instrumental set for several of the dances of the Mareños.

Performers: Eugenio Platas Negrete, master of dance and boxes; Arreveriano Platas, whistle; Luis Clavijero and Casimiro Baloes, turtle shells.

2.- DANCE OF THE SWORDFISH.- This recording includes the complete set: boxes, whistle. shells, drums of cowbells, shouters and whistlers, interpreting the second son of the dance in its most usual form. The battery of cowbells is in charge of three interpreters, who whistle AND shout while percussing and holding the battery, and who receive the name of gentleman, charger and sabanero.

Performers: the same as in Cara A No. 1 and Eligio Negrete, gentleman; Fernando Beltrán, loader; Camilo Miramonte, sabanero.

FACE B

1.- SOUNDS TO SAN MATEO.- Short pieces that are played in the atrium of the church on the day of the patronal festival to pay homage to San Mateo.

These sones are accompanied by a whistle or reed flute with two holes and two tortoise shells; although they admit the inclusion of other instruments, since they are less formalized pieces than the dances.

Performers: Eugenio Platas Negrete, whistle; Luis Clavijero and Casimiro Baloes, turtle shells.

2.- DANCE OF THE SNAKE.- In the Corpus Christi festival this dance is performed, which has a dramatic text. It stages the persecution and death of a snake that kills cattle, at the hands of a shepherd who uses a bow and arrow. Beneath the apparent simplicity of the story, a very complex symbolism is handled: the snake, like men, also lives inside the mountain, and is closely linked to the control of storms, thunder and lightning. In a sense, the dance tells of the struggle between two sets of forces; the terrestrial ones represented by the snake, and the maritime ones like the wind, which rule over the daily life of the Mareños. This dance is accompanied by a six-hole whistle or flute and two double-headed military-type boxes or drums. The voices that are heard are the cries of the snake.

Performers: Eugenio Platas, teacher and box; Arreveriano Platas, whistle; Luis Clavijero, box.

3.- THEY ARE TO GO OUT TO THE CANDLES.- The candles form a cycle of festivals with vague religious pretexts, but with clear secular purposes that are celebrated on the Isthmus under the patronage of a good number of mayordomos. This custom, which seems more clearly Zapotec, has also been adopted by the Huaves, who maintain their own cycle of modest candles. In these the musicians and groups that also participate in the other festivities take part, such as the one in charge of interpreting the dances of the swordfish and the blacks. Apparently the introduction of candles is a recent phenomenon that has not generated its own musical repertoire, but uses a less formalized adaptation of the repertoire of traditional dances to accompany the festivities paid for by the mayordomo.

Performers: Same as in Cara A. No. 2.

4.- DANCE OF THE MALINCHES.- This dance, which is performed at religious festivals, especially Corpus Christi, is the one that most clearly shows the impact of evangelization and its consequence, westernization. The dance is performed by a gang of eight young people who form two rows and perform concerted movements. The dancers dressed in blue pants, white shirts, headdresses with mirrors and turkey feathers and with a shawl hanging from their backs, carry metallic rattles in their right hands, and with them they mark the rhythm of the steps. The dance consists of eight sones, each one with its own name; the included one is called Pico de Oro. This type of dance, which closely resembles the Matachines cycle, is widely practiced by various indigenous groups, and especially among the late evangelized: for this reason it has been suggested that their practice reflects the instruments of evangelization of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Performers: Juan Flores Suárez, representative and drummer; Severo Villaseñor, violin; Odilon Zavaleta, tarolita.

5.- DANCE OF THE TORTOISE.- Dramatic dance that stages the search that the tortoise makes for its parents, touring the entire town. As in the snake dance, a complex symbolism, linked to myths and legends, is expressed through the simplicity of the plot. The turtle, linked to the sea, represents its strength; In addition, the turtle is one of the tonas -soul mate or companion spirit- that children receive after their birth, and to which their destiny will be linked. The turtle dance is accompanied by the whistle and two carapachos, to which the turtle’s voice is added in a recitation.

Performers: same as in Cara B, No. 1.

6.- DANCE OF THE BLACKS.- In this dance, which consists of five songs, two or three blacks and the grandmother take part. All of them dress grotesquely with the clear intention of ridiculing the mestizos, in this case, the Zapotecs of the major cities. of the isthmus. Granny, also a male dancer, mockingly represents the merchants; she brings a basket loaded with unlikely items which she vigorously tries to sell to blacks, with whom she strikes up a jocular dialogue. The blacks form a troupe who are allowed to tease and make heavy jokes throughout the duration of the party in which the dance is performed. The dance of the blacks is widespread throughout the state of Oaxaca, and in all its versions it retains the satirical tone and the mocking intention regarding the exploiters of the large indigenous population.

Performers: same as Cara A. No. 2.

Notes by Arturo Warman.

Secretary of Public Education, Mr. Porfirio Muñoz Ledo

Undersecretary of Culture and Popular Dissemination, Mr. Víctor Flores Olea

Director of the National Institute of Anthropology and History, Professor Gastón García Cantú

Director of Museums, Professor Iker Larrauri

Coordinator of the Disc Series, Professor Ma. Cristina S. de Bonfil

Director of the Disc Series, teacher Irene Vázquez Valle

Mexico, 1977 © 2nd. edition.

Tracklist:

MUSIC OF THE HUAVES OR MAREÑOS

SIDE 1

- A1 Swordfish Dance

Performers: Eugenio Platas Negrete, master of dance and boxes; Arreveriano Platas, whistle; Luis Clavijero and Casimiro Baloes, turtle shells. - A2 Swordfish Dance

Performers: Eugenio Platas Negrete, master of dance and boxes; Arreveriano Platas, whistle; Luis Clavijero; Casimiro Baloes, tortoise shells. Eligio Negrete, gentleman; Fernando Beltrán, loader; Camilo Miramonte, sabanero.

SIDE 2

- B1 Sounds to San Mareo

Performers: Eugenio Platas Negrete, whistle; Luis Clavijero and Casimiro Baloes, turtle shells. - B2 Snake Dance

Performers: Eugenio Platas Negrete, master of dance and boxes; Arreveriano Platas, whistle; Luis Clavijero, box. - B3 They are to go out to the sails

Performers: Eugenio Platas Negrete, master of dance and boxes; Arreveriano Platas, whistle; Luis Clavijero; Casimiro Baloes, tortoise shells. Eligio Negrete, gentleman; Fernando Beltrán, loader; Camilo Miramonte, sabanero. - B4 Dance of the Malinches

Performers: Juan Flores Suárez, representative and drummer; Severo Villaseñor, violin; Odilon Zavaleta, tarolita. - B5 Turtle Dance

Performers: Eugenio Platas Negrete, whistle; Luis Clavijero and Casimiro Baloes, turtle shells. - B6 Black Dance

Performers: Eugenio Platas Negrete, master of dance and boxes; Arreveriano Platas, whistle; Luis Clavijero; Casimiro Baloes, tortoise shells. Eligio Negrete, gentleman; Fernando Beltrán, loader; Camilo Miramonte, sabanero.

Credits:

Secretary of Public Education, Mr. Porfirio Muñoz Ledo

Undersecretary of Culture and Popular Dissemination, Mr. Víctor Flores Olea

Director of the National Institute of Anthropology and History, Professor Gastón García Cantú

Director of Museums, Professor Iker Larrauri

Coordinator of the Disc Series, Professor Ma. Cristina S. de Bonfil

Director of the Disc Series, teacher Irene Vázquez Valle

Arturo Warman: Engraver, Adjunct Material Writer

Saúl Millán: Associate material writer

Paola García Souza: Associate material writer

Victor Acevedo Martínez: Editor

Martín Audelo Chícharo: Editor

Guadalupe Loyola Zárate: Editor

Benjamín Muratalla: Editor, Director

Irene Vázquez Valle: Editor

H. Alejandro Castellanos Garrido: Editor, Researcher

Gabriela González Sánchez: Editor

Mónica Zamora Garduño: Editor

Guillermo Pous Navarro

Alfredo Huertero Casarrubias: Illustrator

Guillermo Santana Ramírez: Designer

Eugenio Platas Negrete: Musician

Arreveriano Platas: Musician

Luis Clavijero: Musician

Casimiro Baloes: Musician

Eligio Negrete: Musician

Fernando Beltrán: Musician

Camilo Miramonte: Musician

Notes:

Notes by Arthur Warman.