|

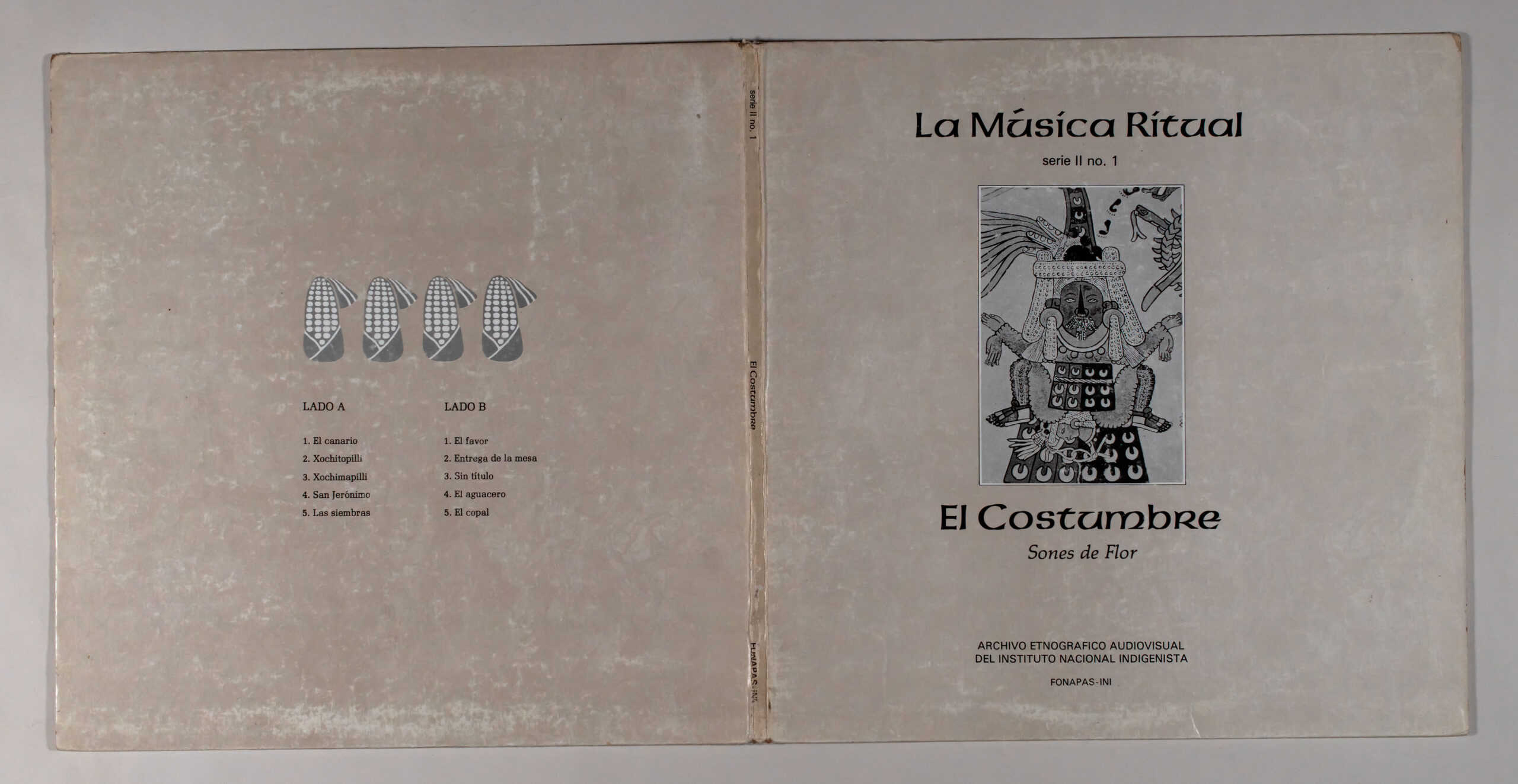

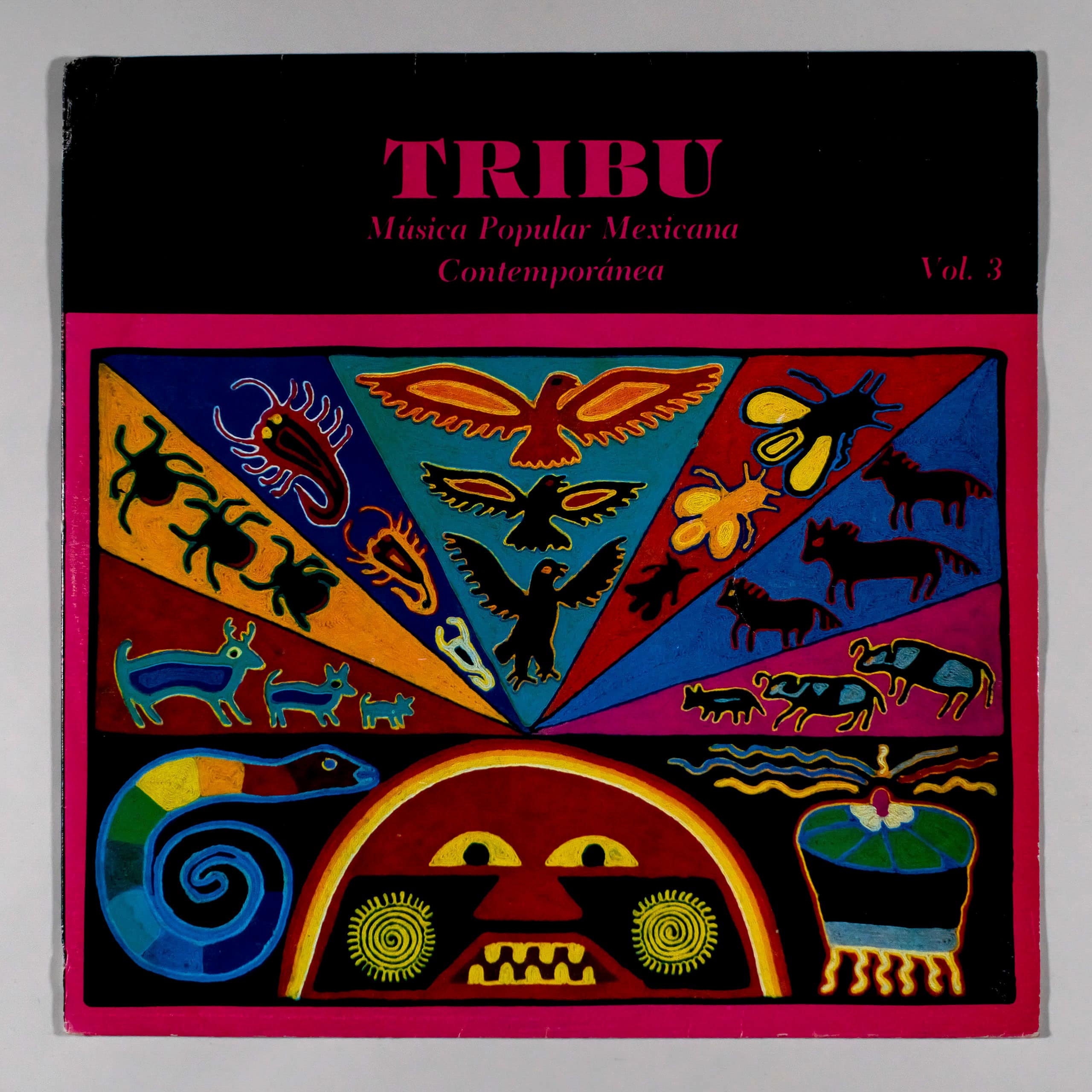

Label: FONAPAS-INI SERIES II, no. 1 |

Country: Mexico Genre: Folk World & Country |

Info:

Ritual Music

II series no. 1

The Custom

Sones of Flower

AUDIOVISUAL ETHNOGRAPHIC ARCHIVE OF THE NATIONAL INDIGENIST INSTITUTE

FONAPAS-INI

I help all my brothers, as medical doctors. I am also like that, to help my brothers. The boy went to see me, he called me, I made him a promise, so that he would have little animals, so that he would have chicks, turkeys, little pigs, like this, the Miguel Cuervo Contreras seed,

Nahua healer from the Veracruz Huasteca.

THE CUSTOM

INTRODUCTION

Music and ethnomusic

The history of Western music begins with the invention of its writing, in the same way that the general history of man begins, for Western thought, with the invention of conventional signs to express his social action and his spiritual environment. However, the forms that precede writing as a relation of tribal facts through the word –whose record is named as oral tradition–, are the same source of knowledge of the being and doing of primitive man as a symptom of his mystery, of his enigma.

So then, in the moments prior to the capture by means of signs of the living sound movement, music was also part of the lives of men and accompanied them in their hunting actions, gathering fruits, and even more: in their social bond and in his relationship with the gods. The survival of ethnic groups in whose vital interweaving original forms that music, dance, representation, words and colors remain, has stimulated the development of disciplines that, like ethnomusic, allow us to investigate the past of our spirit –and through art, into the philosophical abyss of man–.

Indigenous music

Historically, man has explained natural phenomena in terms of magic and myth and has sometimes elevated sound to the category of cosmic elemental force, using it to communicate with the gods and to communicate with their dead.

Some cultures identify or have identified spirits heard through instruments. Along the same lines, noises and sounds produced by animals are also imitated or have been imitated. Imitation thus becomes a form of mythical participation and relates music to the negative or positive powers of the spirits that embody good or evil. By assuming functions in the rite and in magic, music ceases to be just “the art of combining sounds and time well” and is integrated into the living time of men.

Considering that music can be a means of spiritual connection, help at work or simple expression of joy for obtaining favors attributed to supernatural entities, there has been talk of the spiritual utilitarian function, in which two aspects are broken down: the magical and the religious. In the first case, the man uses music to invoke different types of help (it rains or stops raining; that the harvest –hunting or fishing– is abundant; that the petitioner acquires qualities and characteristics of specific animals, etc. .); in the second case, certain processions and prayers are registered that are accompanied with songs, and, likewise, certain dances, promises and “mandas”.

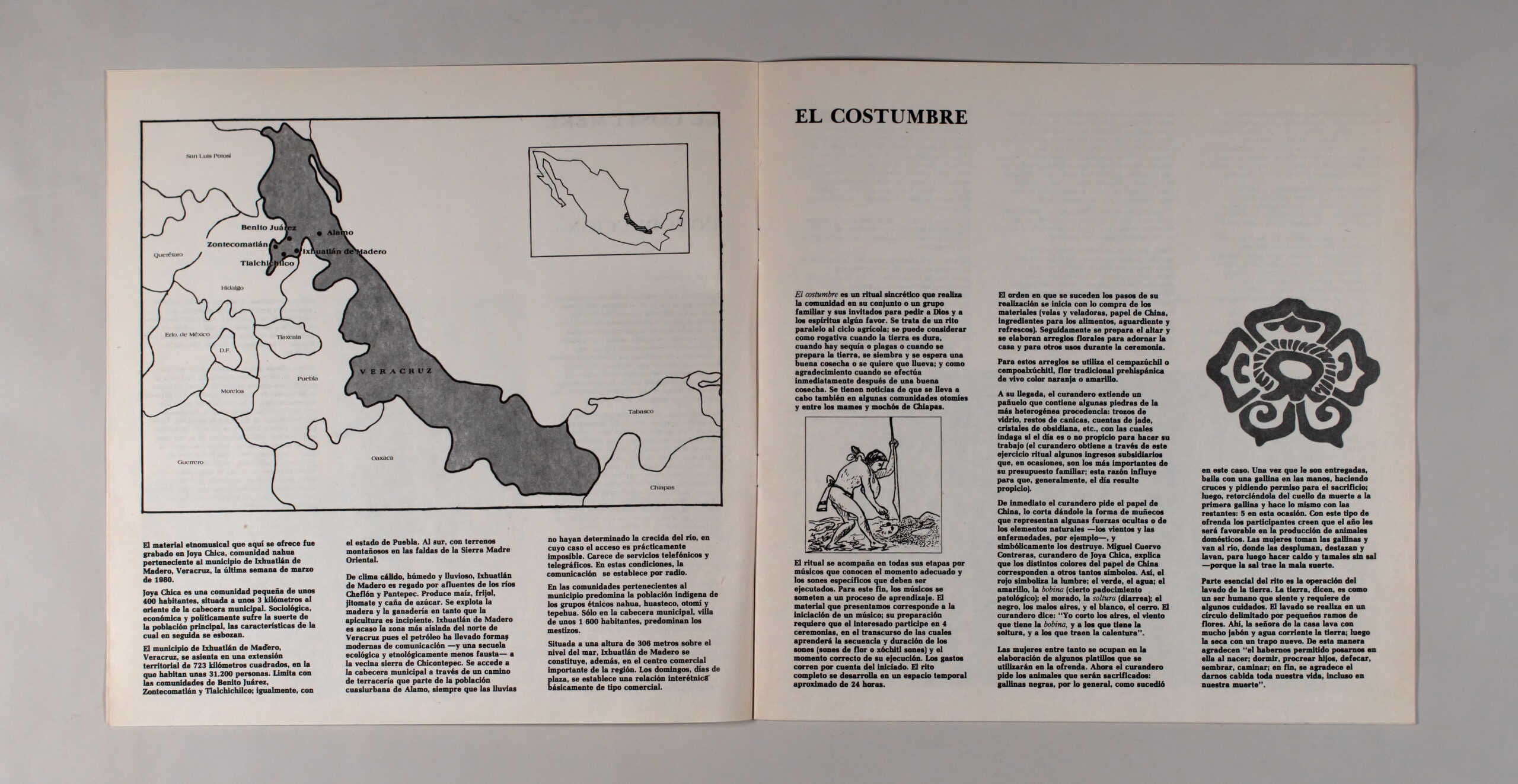

The ethnomusical material offered here was recorded in Joya Chica, a Nahua community belonging to the municipality of Ixhuatlán de Madero, Veracruz, the last week of March 1980. Joya Chica is a small community of about 400 inhabitants, located about 3 kilometers to the east of the municipal seat. Sociologically, economically and politically the fate of the main population suffers, the characteristics of which are outlined below. The municipality of Ixhuatlán de Madero, Veracruz, is located in a territorial extension of 723 square kilometers, in which some 31,200 people live. It limits with the communities of Benito Juárez, Zontecomatlán and Tlachichilco; likewise, with the state of Puebla. To the south, with mountainous terrain on the slopes of the Sierra Madre Oriental.

With a hot, humid and rainy climate, Ixhuatlán de Madero is irrigated by tributaries of the Cheflón and Pantepec rivers. It produces corn, beans, tomato and sugar cane. Wood and livestock are exploited while beekeeping is incipient. Ixhuatlán de Madero is perhaps the most isolated area in northern Veracruz, as oil has brought modern forms of communication –and a less fortunate ecological and ethnological sequel– to the neighboring Sierra de Chicontepec. The municipal seat is accessed through a dirt road that starts from the quasi-urban population of Álamo, provided that the rains in which access is the case have not caused the river to rise, practically impossible. It lacks telephone and telegraphic services. Under these conditions, communication is established by radio.

In the communities belonging to the municipality, the indigenous population of the Nahua, Huasteco, Otomí and Tepehua ethnic groups predominates. Only in the municipal seat, a town of about 1,600 inhabitants, do the mestizos predominate.

Located at a height of 306 meters above sea level, Ixhuatlán de Madero is also the most important commercial center in the region. On Sundays, days of the market, an inter-ethnic relationship is established, basically of a commercial nature.

THE CUSTOM

The custom is a syncretic ritual performed by the community as a whole or by a family group and their guests to ask God and the spirits for a favor. It is a rite parallel to the agricultural cycle; it can be considered as a prayer when the earth is hard, when there is drought or plagues or when the land is prepared, it is planted and a good harvest is expected or it is wanted to rain; and as thanks when it is done immediately after a good harvest. There is news that it is also carried out in some Otomí communities and among the Mamés and Mochós of Chiapas.

The ritual is accompanied in all its stages by musicians who know the right moment and the specific sounds that must be played. To this end, the musicians undergo a learning process. The material that we present corresponds to the initiation of a musician; Its preparation requires that the interested party participate in 4 ceremonies, during which he will learn the sequence and duration of the sones (sones de flor or xóchitl sones) and the correct moment of their execution. Expenses are borne by the initiate. The complete rite takes place in a temporary space of approximately 24 hours.

The order in which the steps of its realization follow one another begins with the purchase of the materials (candles and candles, Chinese paper, ingredients for food, brandy and soft drinks). Next, the altar is prepared and floral arrangements are made to decorate the house and for other uses during the ceremony.

For these arrangements, the cempazúchil or cempoalxúchitl is used, a traditional pre-Hispanic flower of bright orange or yellow color.

Upon arrival, the healer extends a handkerchief containing some stones of the most heterogeneous origin: pieces of glass, remains of marbles, jade beads, obsidian crystals, etc., with which he inquires whether or not the day is propitious for doing his job (the healer obtains through this ritual exercise some subsidiary income that, on occasions, is the most important part of his family budget; this reason influences so that, generally, the day is auspicious).

The healer immediately asks for China’s paper, cuts it out in the shape of dolls that represent some hidden forces or natural elements –winds and diseases, for example–, and symbolically destroys them. Miguel Cuervo Contreras, a healer from Joya Chica, explains that the different colors of the China paper correspond to many other symbols. Thus, red symbolizes the fire; green, water; yellow, the coil (certain pathological condition); purple, looseness (diarrhea); the black, the bad airs, and the white, the hill. The healer says: “I cut the air, the wind that has the coil, and those that have the ease, and those that bring fever.”

Meanwhile, the women are busy preparing some dishes that will be used in the offering. Now the healer asks for the animals that will be sacrificed: black chickens, generally, as happened in this case. Once they are delivered to him, he dances with a chicken in his hands, making crosses and asking permission for the sacrifice; then, twisting her neck, he kills the first hen and does the same with the rest: 5 this time. With this type of offering, the participants believe that the year will be favorable for them in the production of domestic animals. The women take the chickens and go to the river, where they pluck, slaughter and wash them, to later make broth and tamales without salt –because salt brings bad luck–.

An essential part of the rite is the operation of washing the land. The earth, they say, is like a human being who feels and requires some care. Washing is done in a circle delimited by small bouquets of flowers. There, the lady of the house washes the earth with lots of soap and running water; then she dries it with a new rag. In this way, they thank “for having allowed us to perch on it at birth; sleep, procreate children, defecate, sow, walk; in short, they are grateful for giving us room for our entire lives, even in our death.”

Then the participants prepare other “secondary” altars with crosses of branches and flowers, in the kitchen (the stove), the patio and the river. This gives way to the bath of the cobs. Maize, which gave rise to the Huastec, and which personifies mythical beings among the Nahuas, is revered through 4 ears of corn that are bathed and dressed: 2 male and 2 female.

According to their sex, they are put on clothes, earrings, necklaces, etc., a task that is carried out by specially chosen godparents (usually children or adolescents). Once dressed, the corncobs become “the promise” or “the holy table.”

In this regard, Cuervo says: “The seed is a creature. Yes, it was a creature. That’s why we dress it. We are Mexicans; we have a history”, and with these words he refers to the following legend that Bonifacio Hernández narrates: “There was a farmer who celebrated a holy promise, invited his compadre, a landowner, a landowner.

This one arrived when the flowers and offerings were laid out. About noon a child came to present himself, and this is how he represented himself at the holy table; that is, he considers himself as the child God. Then the landowner sat down to eat, but the child God got dirty at the table. The landowner got angry and grabbed him with his quarters, causing several injuries. He told her that he had come to the table because he represented the seed of what we eat today, of what humanity eats. And to you who have quartered me, hit me, offended me, hurt me, I tell you forever that even if you want me to return to cultivate myself, I will never accept. I am leaving this promise, and I will only leave my clothes.

The peasant, that is, the indigenous person, could not do anything to keep his body, and, by divine command, the child transformed into a bird and flew towards San Jerónimo.

Since then, the seed has been washed, because it is what he left us: his clothes, nothing more; And that is why his spirit comes to see the party that we throw for him, the custom that those of us who remember him make for him, because to tell the truth he is already disappearing, but some of us still have a lot of affection for him.

When the food is ready, they are offered on all the altars and then the offering is prepared to be taken to the hill. At dawn, the participants march to the top of the chosen hill –in this case, the same one where the farmland is. The musicians who have accompanied each phase of the ritual continue to play along the way. Upon arrival, another altar is built to perform the last prayers, at the same time that offerings are made and watered with brandy and soda. They do this because, as the healer says: “When the world ended, there were some gentlemen who had their houses there on the hill; now they don’t want to eat, and that’s why we go and make an offering, because they ask us to give them there.” .

The initiated musician and his wife are crowned with cempoalxóchitl, they are the object of a cleansing and a request is made for them. Finally, one or two more sones are danced.

Thus concludes the ritual. Man has made peace with the forces that govern nature and men. The participants return, tired but satisfied. They have faith that they have been heard: the land will be fertile, the harvest abundant, diseases and ills at bay, domestic animals, in short, will reproduce, more prodigal, and the musician will have taken a step: on his way as a musician of flower sounds, so that it continues, so that the custom is not forgotten.

BRIEF MUSICAL ANALYSIS

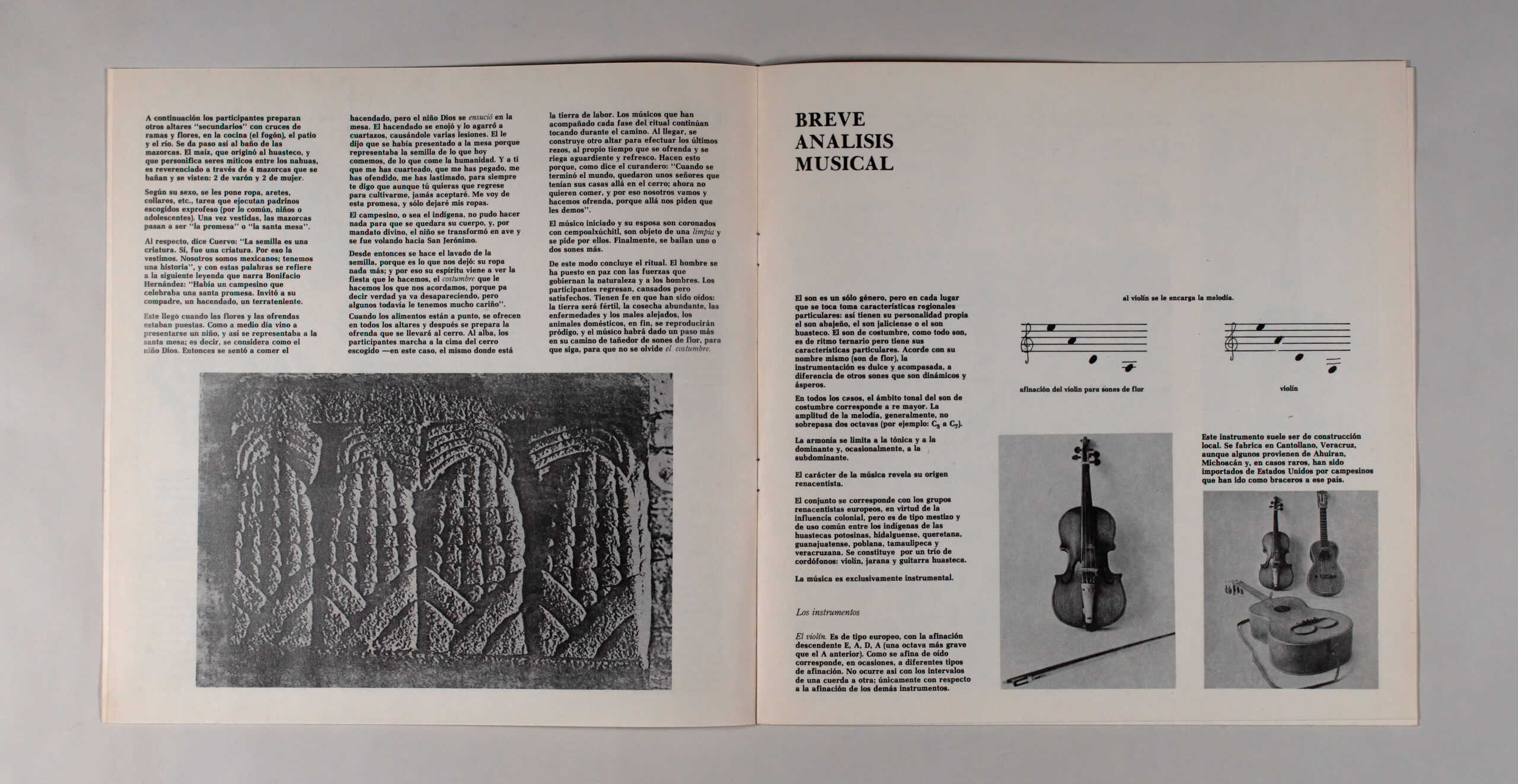

The son is a single genre, but in each place it is played it takes on particular regional characteristics: this is how the son abajeño, the son from Jalisco or the son from Huasteco have their own personality. The usual son, like all sons, has a ternary rhythm but has its own particular characteristics. In keeping with its name (son de flor), the instrumentation is sweet and rhythmic, unlike other sones that are dynamic and rough.

In all cases, the tonal scope of the son de habitual corresponds to D major. The amplitude of the melody, generally, does not exceed two octaves (for example: C₅ to C₂).

Harmony is limited to the tonic and dominant, and occasionally the subdominant.

The character of the music reveals its Renaissance origin.

The set corresponds to the European Renaissance groups, by virtue of colonial influence, but it is of a mestizo type and in common use among the indigenous people of the Huastecas from Potosi, Hidalguense, Queretaro, Guanajuato, Puebla, Tamaulipas and Veracruz. It is made up of a trio of chordophones: violin, jarana and Huasteca guitar.

The music is exclusively instrumental.

The instruments

The violin. It is of the European type, with descending tuning E. A, D, A (one octave lower than the previous A). As it is tuned by ear, it sometimes corresponds to different types of tuning. Not so with intervals from one string to another; only with respect to the tuning of the other instruments. The violin is responsible for the melody.

This instrument is usually locally built. It is made in Cantollano, Veracruz, although some come from Ahuiran, Michoacán and, in rare cases, have been imported from the United States by peasants who have gone to that country as braceros.

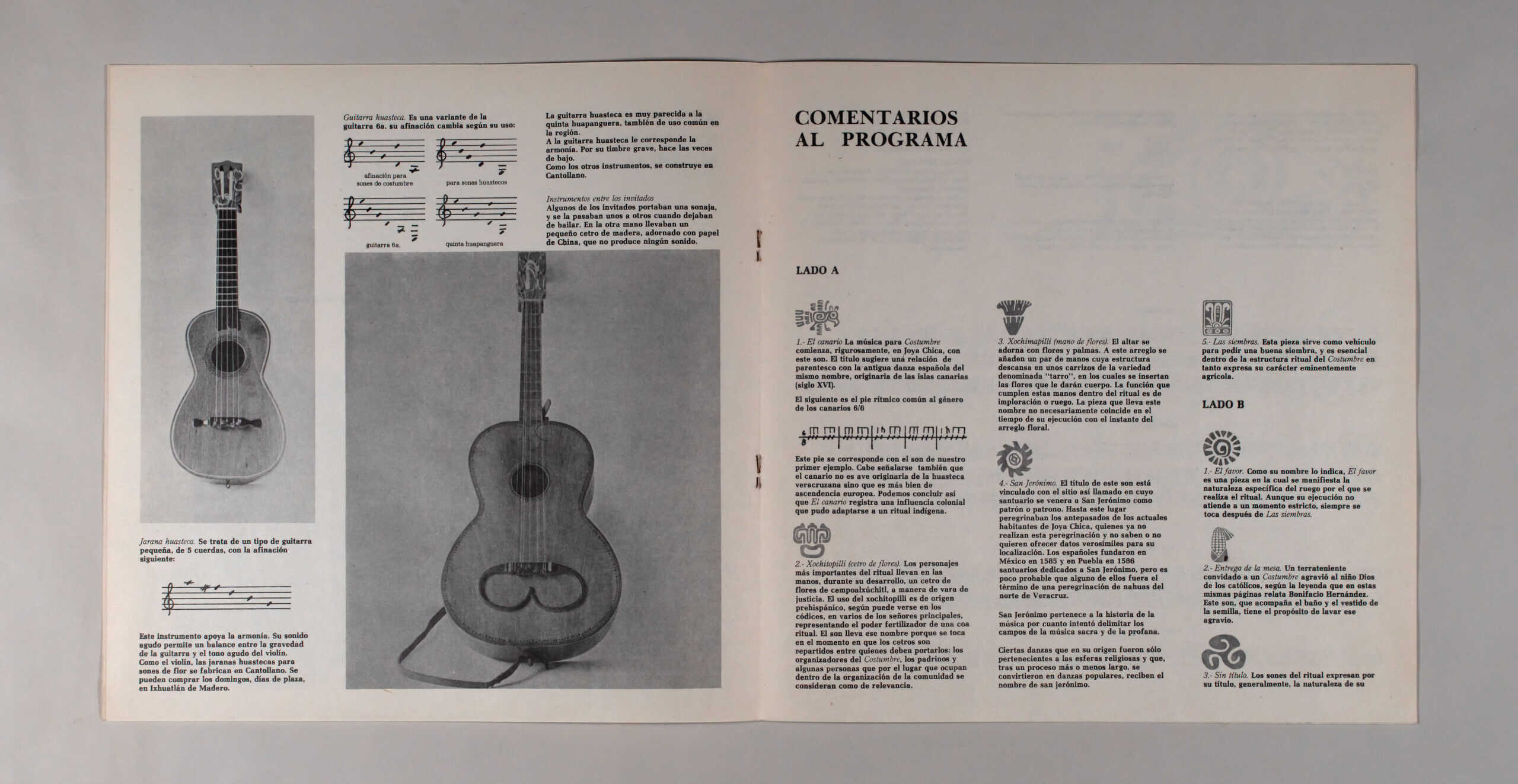

Huastec revelry. It is a type of small guitar, with 5 strings.

This instrument supports harmony. Its sharp sound allows a balance between the gravity of the guitar and the sharp tone of the violin. Like the violin, the Huastec jaranas for sones de flor are made in Cantollano. They can be bought on Sundays, market days, in Ixhuatlán de Madero.

Huastec guitar. It is a variant of the 6a guitar. its tuning changes according to its use: for customary sounds, 6a guitar, for huasteco sounds, quinta huapanguera.

The Huasteca guitar is very similar to the quinta huapanguera, also in common use in the region.

Harmony corresponds to the Huasteca guitar. Due to its serious timbre, it acts as a bass.

Like the other instruments, it is built in Cantollano.

Instruments among the guests

Some of the guests carried a rattle, and passed it to each other when they stopped dancing. In the other hand they carried a small wooden scepter, adorned with tissue paper, which makes no sound.

COMMENTS TO THE PROGRAM

SIDE A

1.- The canary. The music for Costumbre begins, rigorously, in Joya Chica, with this son. The title suggests a kinship relationship with the ancient Spanish dance of the same name, originally from the Canary Islands (16th century).

The following is the rhythmic foot common to the genre of canaries 6/8.

This foot corresponds to the son of our first example. It should also be noted that the canary is not a bird native to the Huasteca of Veracruz but is rather of European descent. Thus, we can conclude that El canario registers a colonial influence that could have been adapted to an indigenous ritual.

2.- Xochitopilli (scepter of flowers). The most important characters in the ritual carry in their hands, during its development, a scepter of cempoalxóchitl flowers, as a rod of justice. The use of the xochitopilli is of pre-Hispanic origin, as can be seen in the codices, in several of the main lords, representing the fertilizing power of a ritual coa. The son bears that name because it is played at the moment when the sceptres are distributed among those who must carry them: the organizers of the Custom, the godparents and some people who, due to the place they occupy within the organization of the community, are considered relevant.

3.- Xochimapilli (hand of flowers). The altar is decorated with flowers and palms. To this arrangement are added a pair of hands whose structure rests on some reeds of the variety called “jar”, in which the flowers that will give it body are inserted. The function that these hands fulfill within the ritual is imploration or request. The piece that bears this name does not necessarily coincide in the time of its execution with the moment of the floral arrangement.

4.- Saint Jerome. The title of this son is linked to the so-called site in whose sanctuary Saint Jerome is venerated as patron or patron. The ancestors of the current inhabitants of Joya Chica made a pilgrimage to this place, who no longer make this pilgrimage and do not know or do not want to offer credible data for their location. The Spanish founded sanctuaries dedicated to Saint Jerome in Mexico in 1585 and in Puebla in 1586, but it is unlikely that either of them was the end of a pilgrimage of Nahuas from northern Veracruz.

Saint Jerome belongs to the history of music because he tried to delimit the fields of sacred and profane music.

Certain dances that originally belonged only to religious spheres and that, after a more or less long process, became popular dances, receive the name of San Jerónimo.

5.- The crops. This piece serves as a vehicle to ask for a good planting, and is essential within the ritual structure of the Custom insofar as it expresses its eminently agricultural character.

SIDE B

1.- The favor. As its name indicates, El favor is a piece in which the specific nature of the request for which the ritual is performed is manifested. Although its execution does not attend to a strict moment, it is always played after Las sowings.

2.- Delivery of the table. A landowner invited to a Custom offended the child God of the Catholics, according to the legend that Bonifacio Hernández recounts in these same pages. This sound, which accompanies the bath and dressing of the seed, has the purpose of washing away that grievance.

3.- Untitled. The sounds of the ritual express by their title, generally, the nature of their interest. However, between one phase and the preparation of another, sones are usually played to fill a waiting bar. Usually these sones do not have a title. We include one of them to exemplify that music.

4.- The downpour. The execution of this son corresponds to the stage prior to the final. It is played at the top of the hill to express that it has been fulfilled and that it is in a position to receive water, an essential element to achieve a good harvest. After this sound, others with names as suggestive as La nube and La llovizna are played.

5.- The copal. With this sound the ritual closes. While being executed, the healer is saying:

Primero Dios nicani muchihauei in se costumbre mu-maituha ni se Dios icuni, ni se Dios, ichamanca se dios ipilca, nicane tlahuatlani nuchi juersa, tlatlani nachi ximachtli, chicumi xúchitl para uncas tle ca pupuse ni Dios incunchaua ni Dios ichamancahua tlahtutuya cayahquie ca la música, como nama ya cumplido.

Which literally means:

“First God, here this became a Custom. Praying this one a God, a luxury, this one a God: his offspring, a creature God, here he paid. He went to fix: now he has fulfilled. Here he asks for all strength, he asks for all seed, seven flowers, so that there is something to spend it with. This God, his son, this God his offspring, has already spoken. He left with the music as now. He has already fulfilled”. (Literal version of Bonifacio Hernández).”

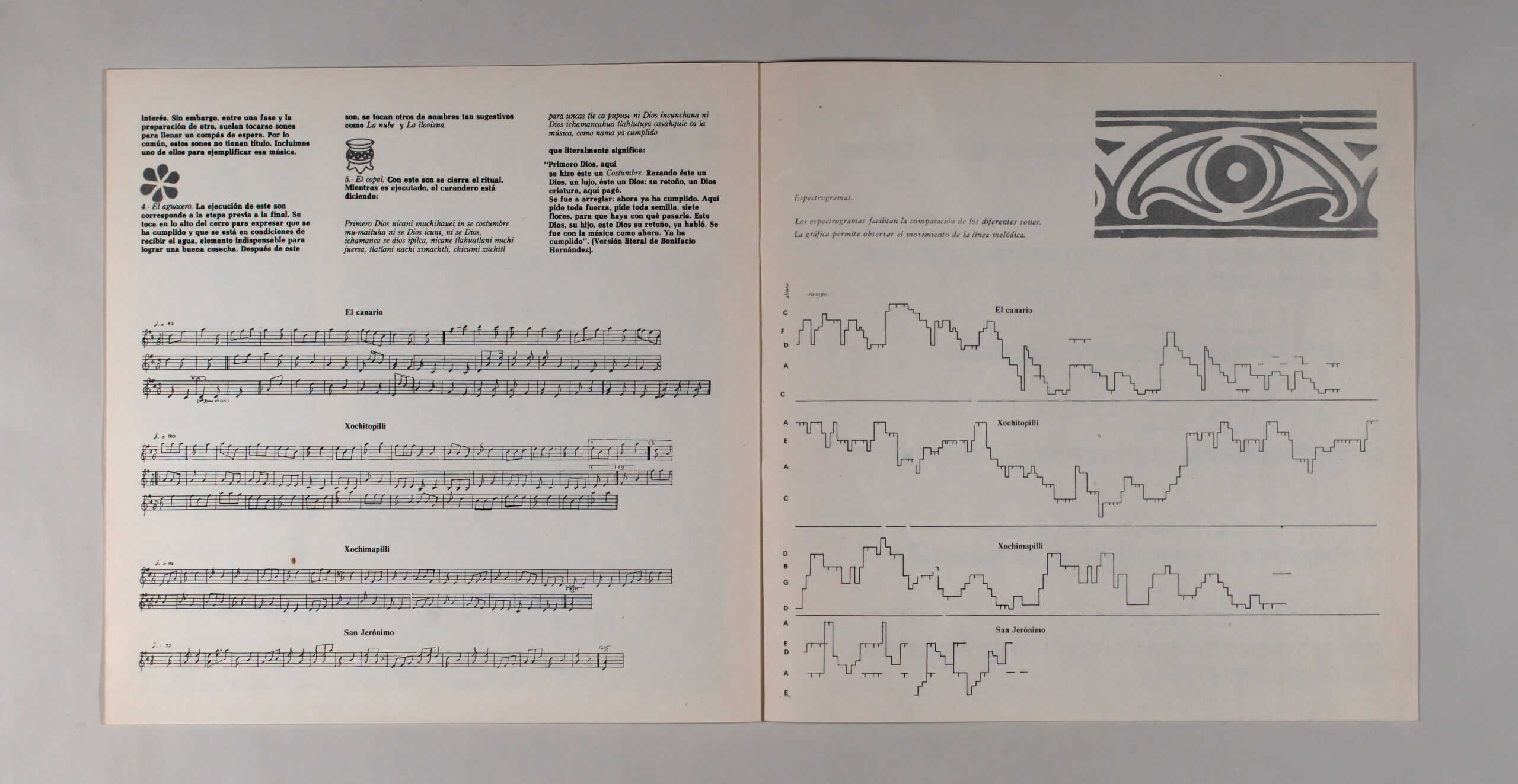

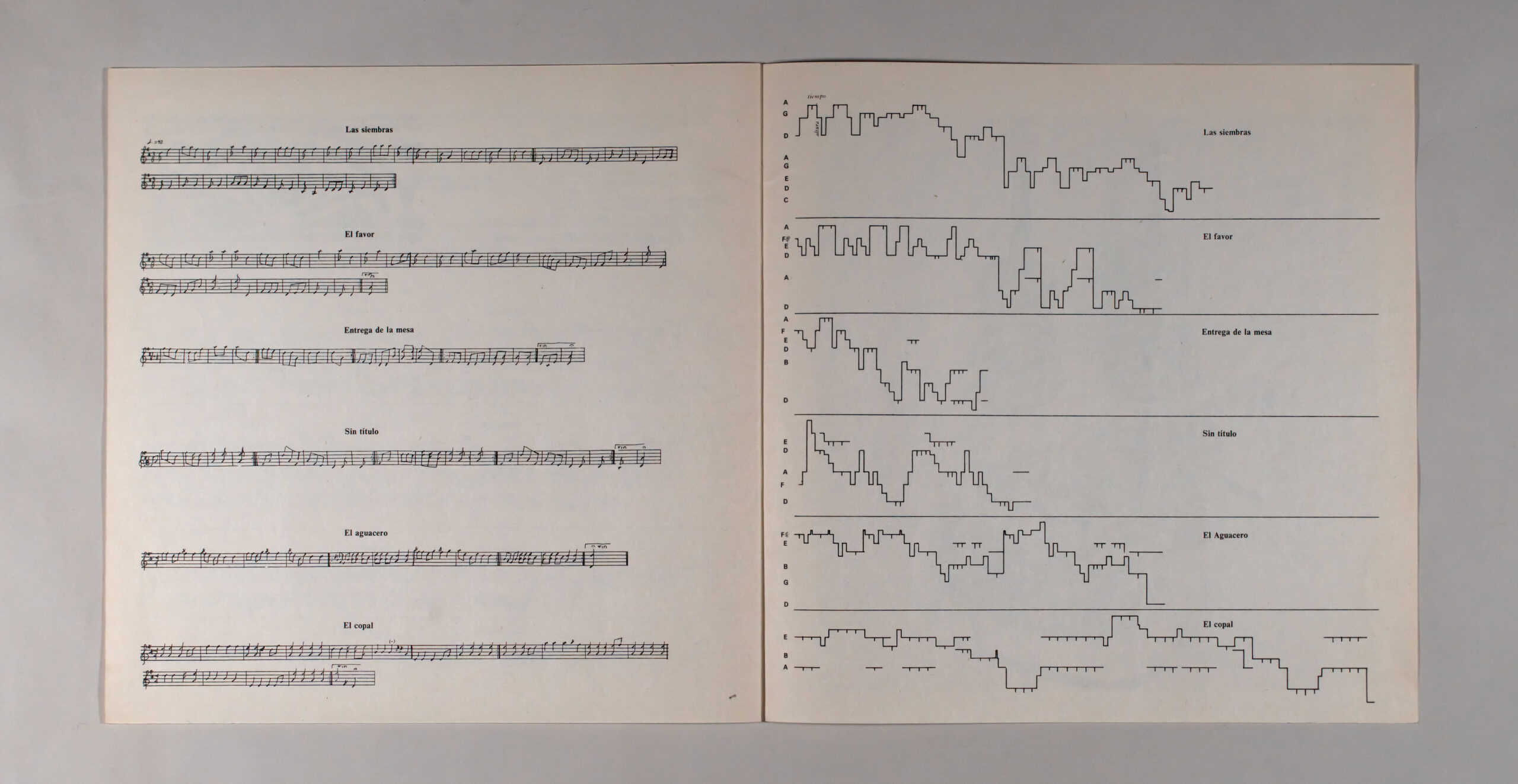

Spectrograms.

Spectrograms make it easy to compare different sones.

The graph allows to observe the movement of the melodic line.

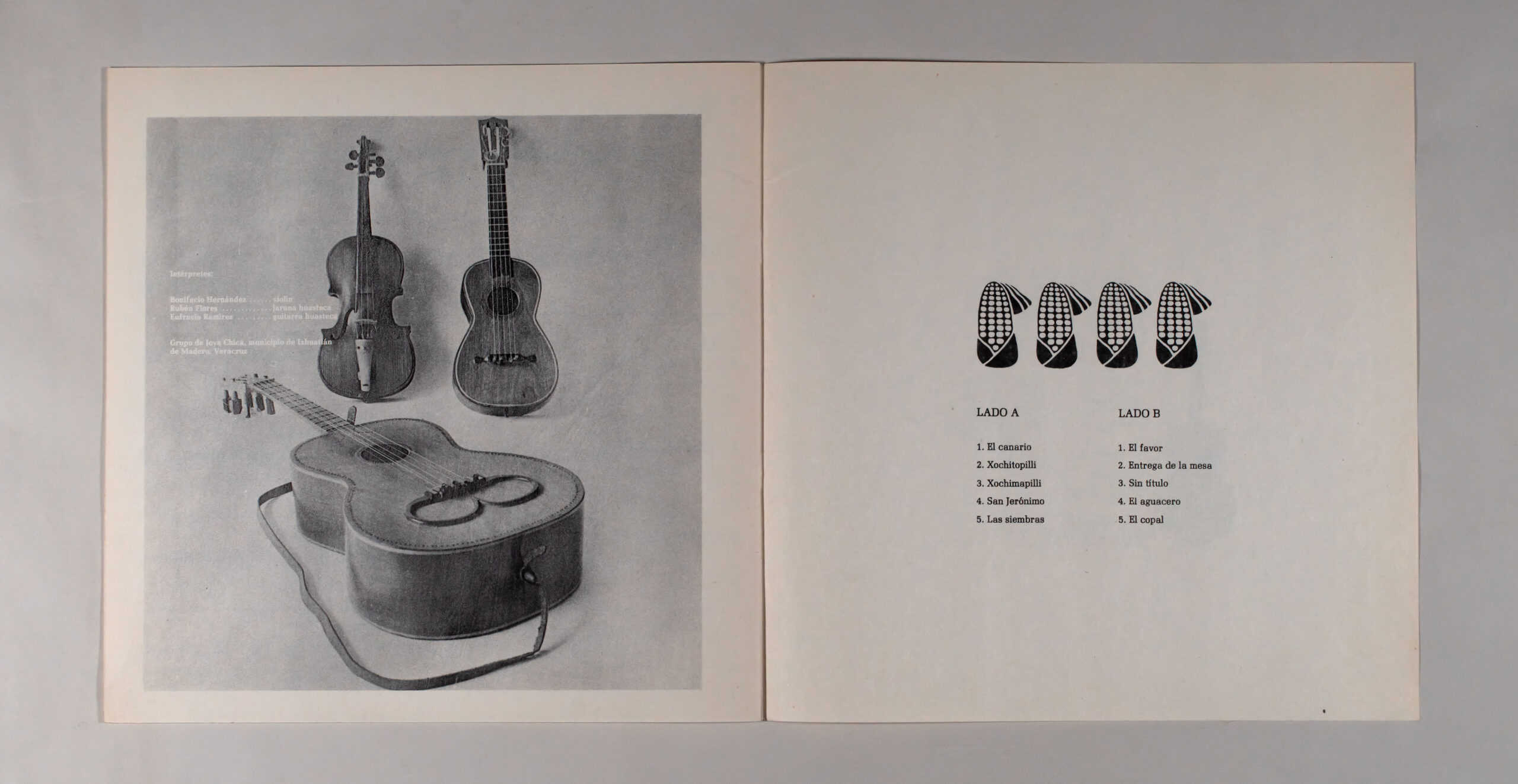

Performers:

Bonifacio Hernandez ……..violin

Rubén Flores…….. Huasteca jarana

Eufracio Ramírez……..Huastecan guitar

Group of Joya Chica, municipality of Ixhuatlán de Madero, Veracruz

SIDE A

- The Canary

- Xochitopilli

- Xochimapilli

- St Geronimo

- The crops

SIDE B

- The favor

- Table delivery

- No title

- The downpour

- The copal

THE RESEARCH TASKS AND COLLECTION OF MATERIALS THAT MADE THE REALIZATION OF THIS ALBUM POSSIBLE WERE ACHIEVED THANKS TO MRS. CARMEN ROMANO DE LOPEZ PORTILLO, PRESIDENT OF THE NATIONAL FUND FOR SOCIAL ACTIVITIES (FONAPAS), FOR THE FINANCING GRANTED TO THE AUDIOVISUAL ETHNOGRAPHIC ARCHIVE OF THE NATIONAL INDIGENIST INSTITUTE WITHIN THE OLLIN YOLIZTLI PROGRAM.

THE EDITION OF THESE CULTURAL REVALUATION MATERIALS WAS ALSO COVERED WITH THE GENEROUS FINANCIAL CONTRIBUTION OF VARIOUS TRADE UNIONS.

ALFRED ELIAS

DIRECTOR OF THE NATIONAL FUND FOR SOCIAL ACTIVITIES

IGNACIO OVALLE FERNANDEZ

GENERAL DIRECTOR OF THE NATIONAL INDIGENIST INSTITUTE

JUAN CARLOS COLIN

HEAD OF THE AUDIOVISUAL ETHNOGRAPHIC ARCHIVE OF THE NATIONAL INDIGENIST INSTITUTE

JOSE ANTONIO GUZMAN

HEAD OF THE ETHNOGRAPHY AND ETHNOMUSICOLOGY UNIT

ANGEL AGUSTÍN PIMENTEL, JESUS HERRERA PIMENTEL AND ALEJANDRO MENDEZ ROJAS

ETHNOMUSICOLOGY UNIT

ANGEL AGUSTIN PIMENTEL DÍAZ AND ALEJANDRO N. MENDEZ ROJAS, FIELD RECORDING; ENRIQUE “HEINI” KUHLMANN, EDITION; MARTHA COVARRUBIAS, DESIGN; GERMÁN HERRERA AND MIGUEL BRACHO, PHOTOGRAPHS; ORLANDO GUILLEN, WRITING AND STYLE.

Tracklist:

THE RITUAL MUSIC / THE CUSTOM (SONES OF FLOWER)

SIDE 1

- A1 The canary

Performer(s): Joya Chica Group: Bonifacio Hernández – violin; Rubén Flores – Huastec jarana; Eufracio Ramírez – Huastec guitar. - A2 Xochitopilli

Performer(s): Joya Chica Group: Bonifacio Hernández – violin; Rubén Flores – Huastec jarana; Eufracio Ramírez – Huastec guitar. - A3 Xochimapilli

Performer(s): Joya Chica Group: Bonifacio Hernández – violin; Rubén Flores – Huastec jarana; Eufracio Ramírez – Huastec guitar. - A4 Saint Jerome

Performer(s): Joya Chica Group: Bonifacio Hernández – violin; Rubén Flores – Huastec jarana; Eufracio Ramírez – Huastec guitar. - A5 The crops

Performer(s): Joya Chica Group: Bonifacio Hernández – violin; Rubén Flores – Huastec jarana; Eufracio Ramírez – Huastec guitar.

SIDE 2

- B1 The favor

Performer(s): Joya Chica Group: Bonifacio Hernández – violin; Rubén Flores – Huastec jarana; Eufracio Ramírez – Huastec guitar. - B2 Delivery of the table

Performer(s): Joya Chica Group: Bonifacio Hernández – violin; Rubén Flores – Huastec jarana; Eufracio Ramírez – Huastec guitar. - B3 Untitled

Performer(s): Joya Chica Group: Bonifacio Hernández – violin; Rubén Flores – Huastec jarana; Eufracio Ramírez – Huastec guitar. - B4 The Downpour

Performer(s): Joya Chica Group: Bonifacio Hernández – violin; Rubén Flores – Huastec jarana; Eufracio Ramírez – Huastec guitar. - B5 The copal

Performer(s): Joya Chica Group: Bonifacio Hernández – violin; Rubén Flores – Huastec jarana; Eufracio Ramírez – Huastec guitar.

Credits:

Alfredo Elias

Director of the National Fund for Social Activities

Ignacio Ovalle Fernandez

General Director of the National Indigenous Institute

Juan Carlos Colin

Head of the Audiovisual Ethnographic Archive of the National Indigenous Institute

Jose Antonio Guzman

Head of the Ethnography and Ethnomusicology Unit

Angel Agustin Pimentel, Jesus Herrera Pimentel and Alejandro Mendez Rojas

Ethnomusicology Unit

Angel Agustín Pimentel Díaz and Alejandro N. Mendez Rojas, Field Recording; Enrique “Heini” Kuhlmann, Editing; Martha Covarrubias, Design; Germán Herrera and Miguel Bracho, Photographs; Orlando Guillen, Writing and Style.

Notes:

The research tasks and collection of materials that made the realization of this album possible were achieved thanks to Mrs. Carmen Romano de López Portillo, president of the national fund for social activities (fonapas), for the financing granted to the audiovisual ethnographic archive of the national indigenous institute within the Ollin Yoliztli program.

The edition of these cultural reassessment materials was also covered by the generous economic contribution of various union groups.