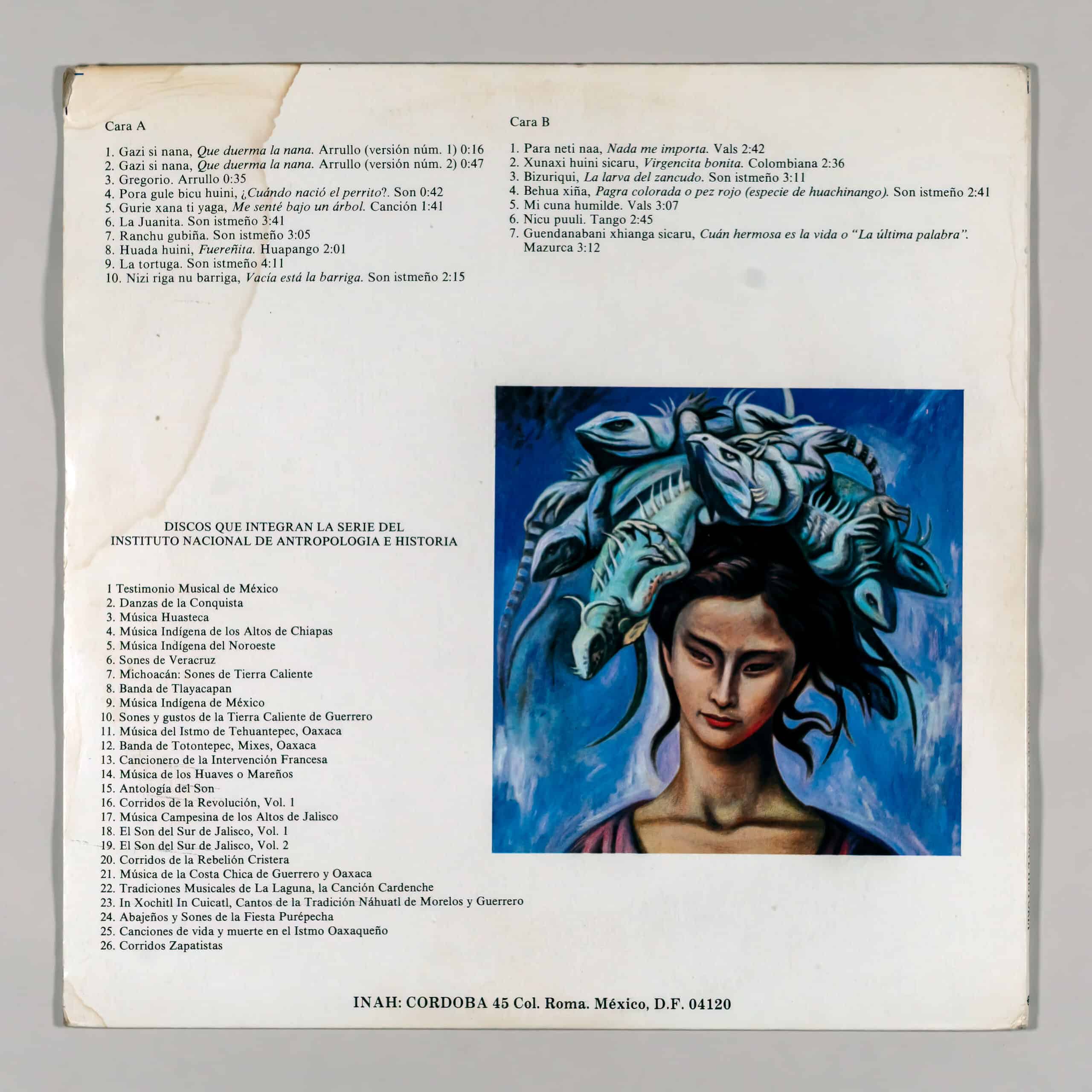

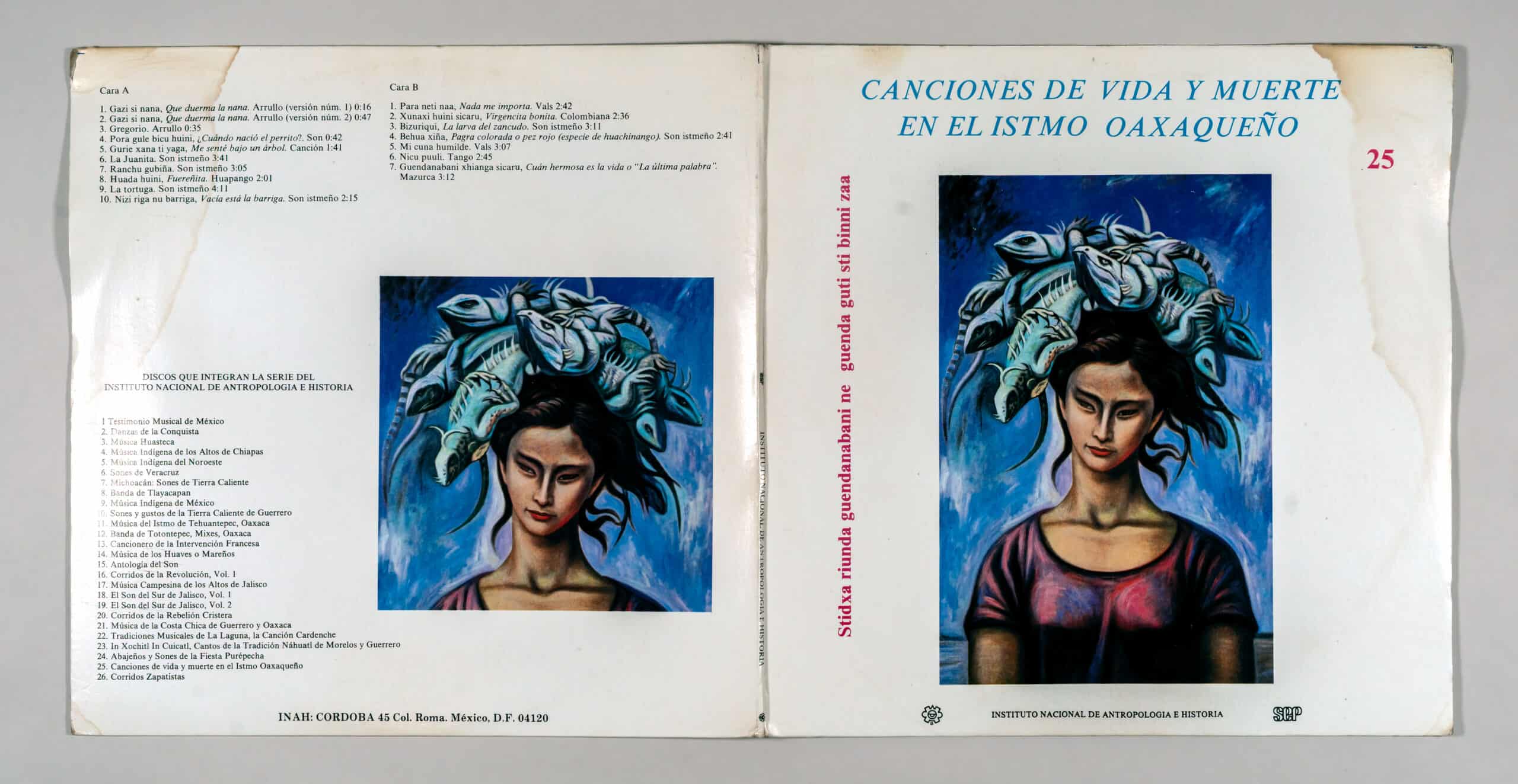

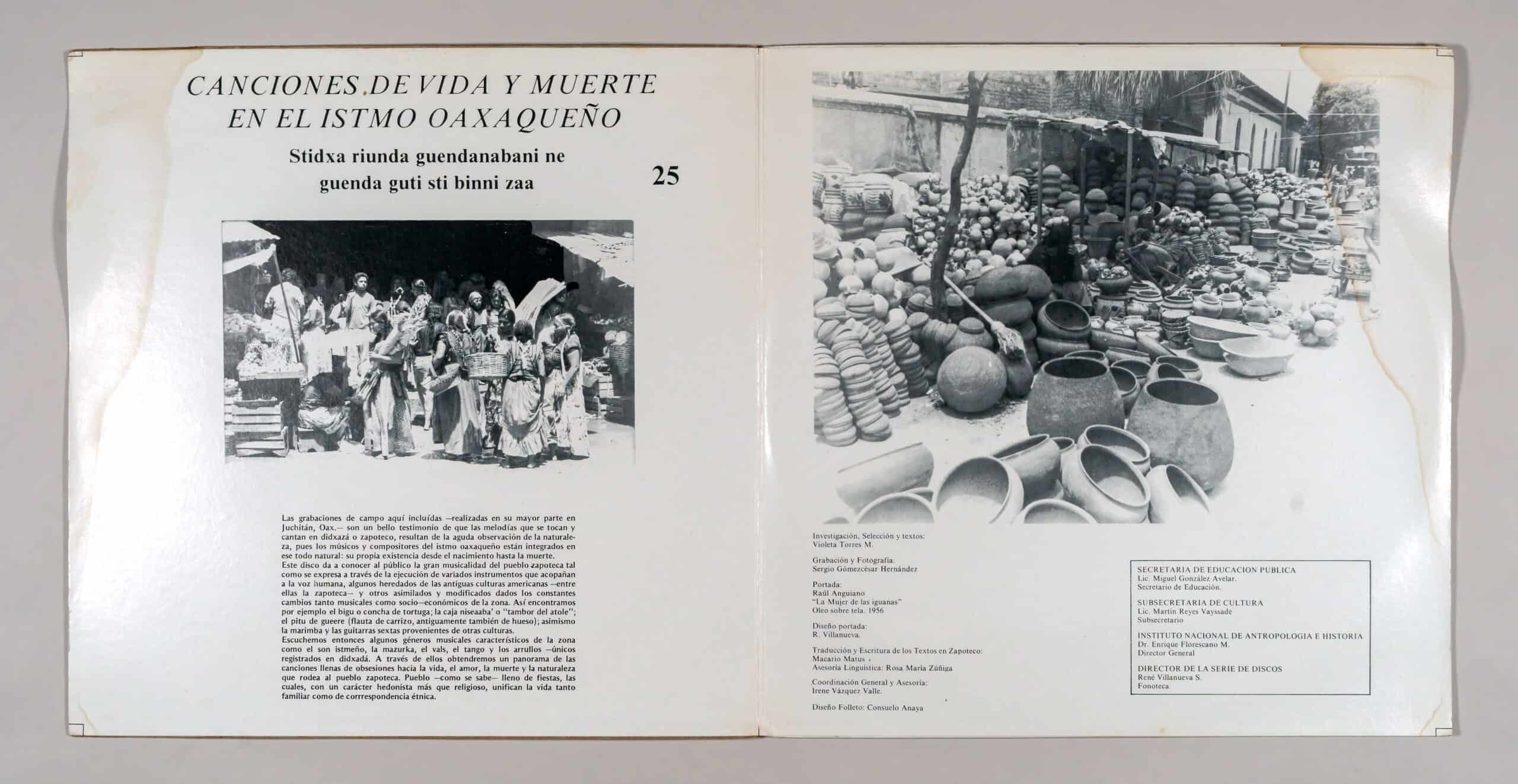

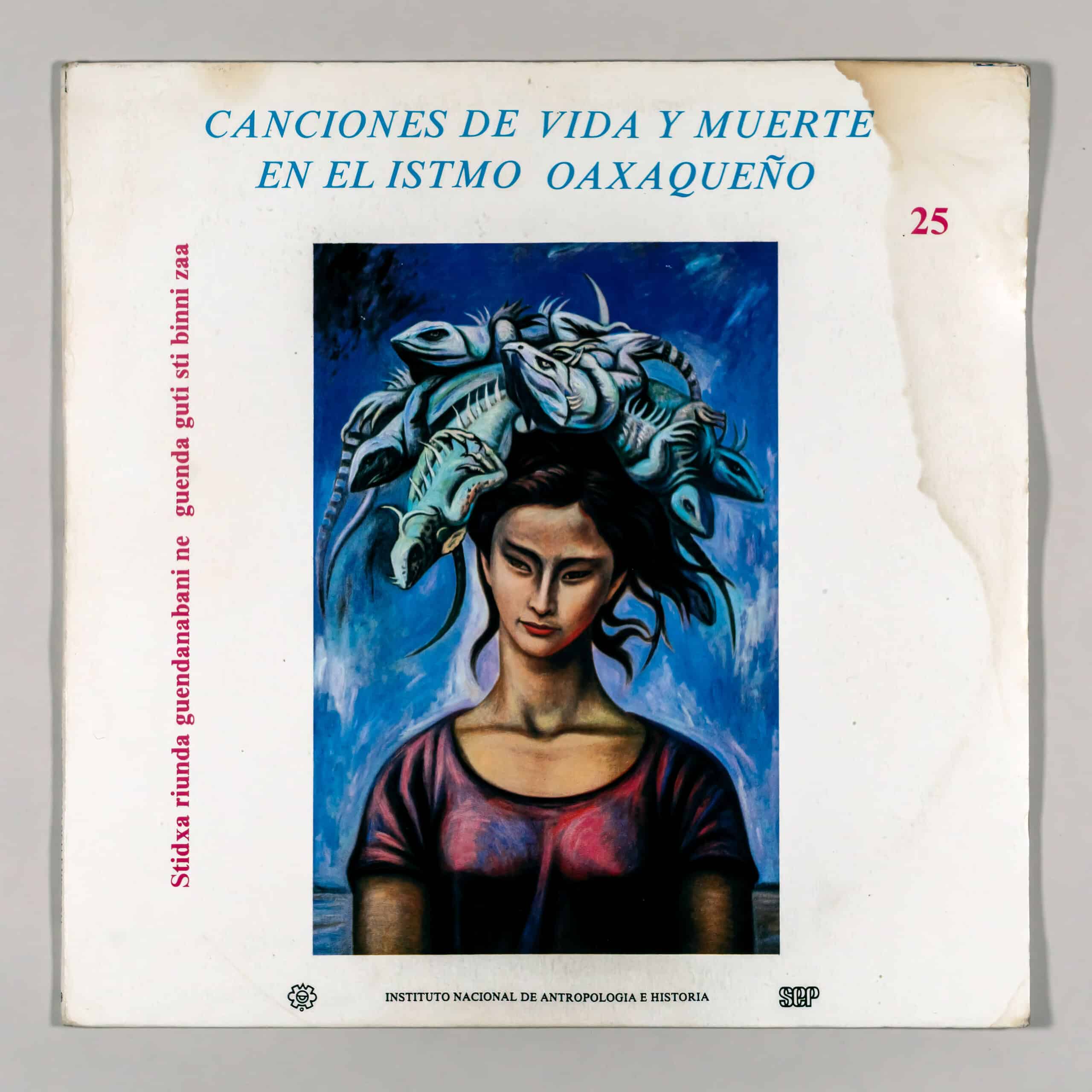

SONGS OF LIFE AND DEATH IN THE OAXACAN ISTHMUS

INAH SEP

|

Label: INAH-SEP INAH-25, LME-167 Released: 1984 |

Country: Mexico |

Info:

Stidxa riunda guendanabani ne guenda guti sti binni zaa

SONGS OF LIFE AND DEATH IN THE OAXACAN ISTHMUS

Disc 25

INAH

The Zapotecs of the Isthmus, a people who fight, work and sing Physical Geography of the Isthmus I called the Isthmus of Tehuantepec is the narrowest part of the Mexican Republic and is located within the states of Veracruz and Oaxaca. The region, which covers the entire area between the Gulf of Mexico and the Gulf of Tehuantepec, is divided into two clearly different subregions: the Veracruz isthmus and the Oaxacan isthmus.¹

Our interest is centered on the Oaxacan isthmus. We define this subregion as the coastal plain that is limited –according to the geographer Jorge Tamayo L.² – by the Sierra Madre del Sur, the Sierra Atravesada, the Sierra Madre de Chiapas and the Gulf of Tehuantepec coast; in its entirety it covers an area of 19,975 km.2, which represents 2.7% of the surface of the state of Oaxaca.³

According to recent studies carried out under the direction of Margarita Dalton, the territory described above is made up of the districts of Juchitán and Tehuantepec, with 22 and 19 municipalities respectively, although Reyna Moguel assures that San Pedro Huamelula and Santiago Astata are improperly included, which correspond in reality to the “coast” of Oaxaca.⁵ The cities of the Oaxacan isthmus are Matías Romero, Juchitán and Salina Cruz (see map).⁶

The formations that connect the Sierra Madres of Oaxaca, and of the South with that of Chiapas, in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec are of low elevation and for this reason Tamayo supposes that in the Cenozoic there was communication between the waters of the Gulf and the Pacific;⁷ he also says The Upper and Lower Lagoons and the so-called Dead Sea remain as remains of the emersion (see map).

The topography of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, according to Royce,⁸ can be divided into three different sections: The first is the Gulf coast; It begins in the Ostión Lagoon, where a concavity begins that ends in the Tonalá bar, in whose central part the Coatzacoalcos river flows. The second is that of the Neovolcanic Cordillera, which, in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, joins the Sierra Madre Atravesada and the Sierra Madre de Oaxaca; it borders the lowlands carved by fluvial currents such as the valley of the Tehuantepec river. Finally, the third part –in the south of the isthmus– is the plain called by Tamayo “Planicie Costera Istmica Chiapaneca”; it is conventionally considered to be bounded by the Tehuantepec River in the Northwest and the Suchiate River in the Southeast.⁹

On the southern slopes –Royce tells us– there are seven rivers that flow into the Upper and Lower Lagoons; These are: Comotepec, Los Perros (or Juchitán), Estacada, Chicapa, Espanta Perros, Niltepec (or Xacuapa) and Ostuta. It should be noted that there is another more important river, the Tehuantepec, whose current –according to Tamayo– flows down from the Sierra Madre del Sur in the vicinity of Miahuatlán, and heads north under the name of Río Ciénega, later changing to Río Ciénega. Mijangos. In the vicinity of Jalapa del Marqués, the Tehuantepec River is joined by the waters of the Tequisistlán River; With these two currents the Benito Juárez dam was built. The Tehuantepec River flows into the Bahía de la Ventosa, in the Pacific Ocean.

The climate is described by Tamayo as “rainy tropical with dry winter”. The rains are scarce but torrential, limited to a short summer season. The dry season is from October to May. The average annual temperature is 28°C and in the hottest months, from May to June, the temperature stays above 32°C. The “nortes” season (strong northwesterly winds) is from November to March and when it ends, the heat is felt with all its force.

Due to the high temperatures in the dry season, the vegetation becomes semi-desert: in general “mesquites, huizaches and thorny legumes that grow on the banks of the rivers”.¹⁰

In the dry season, the landscape is arid, but when the rainy season arrives, everything turns green.

The most characteristic animals are: the skunk, the gopher, the squirrel, the free-range rat, the hare and the wild boar or drum. The typical birds are: the chachalaca, the quail, the lark, the sparrow, the wild verdun, the coyol cozque, the whistling knife, the magpie and the shoemaker.

On the subsoil resources there are not many recent studies, but it is known that there is a great wealth of mica and phosphorite in Matías Romero; important iron deposits in Tehuantepec; magnatela in Guichicovi, La Ventosa, Jalapa del Marqués and in various other points of the isthmus.¹¹

The Isthmus of Tehuantepec has been defined as an economic zone as important as the Panama Canal, since its narrowness allows interoceanic communication. Since pre-Hispanic times, this geophysical feature was contemplated; as well as it was by conquerors, chroniclers; and later, considered by scholars and businessmen, some of them North Americans, who wanted to carry out plans to take advantage of such narrowness.¹² This area, over time, has become a magnificent passage for massive merchandise traffic.

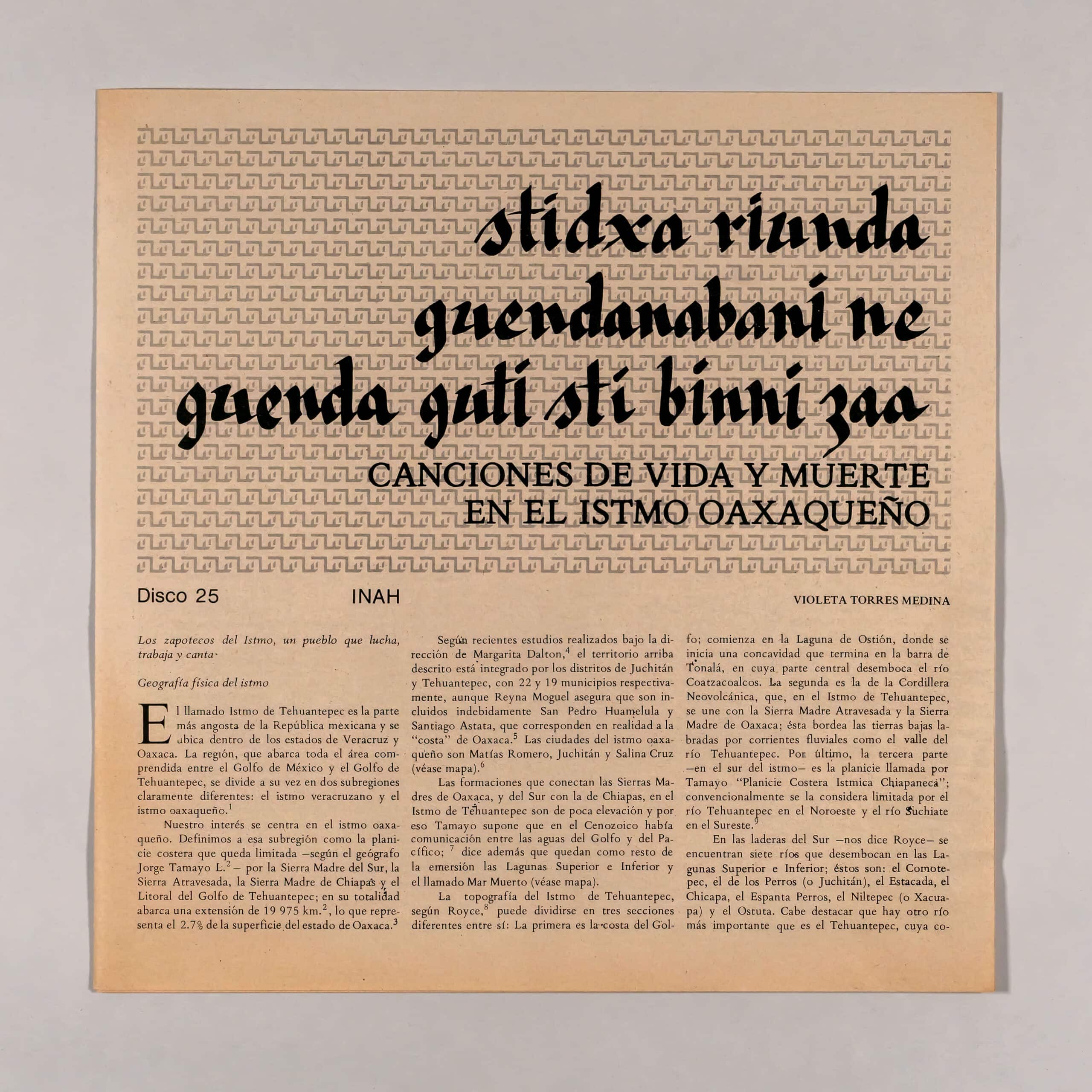

OAXACAN ISTHMUS

TERRITORIAL INTEGRATION: DISTRICTS AND MUNICIPALITIES

I TEHUANTEPEC

1.- Santa Maria Totolapilla

2.- Santiago Lachiguiri

3.- Guevea de Humboldt

4.- Santa María Guienagati

5.- Magdalena Tequisistlán

6.- Santa Maria Jalapa del Marques

7.- Santiago Laollaga

8.- Santo Domingo Chihuitan

9.- Magdalena Tlacotepec

10.- Santa Maria Mixtequilla

11.- San Pedro Comitancillo

12.- San Miguel Tenango

13.- Santo Domingo Tehuantepec

14.- San Blas Atempa

15.- San Pedro Huilotepec

16.- Salina Cruz

17.- San Mateo del Mar

18.- San Pedro Huamelula

19.- Santiago Astata

II JUCHITAN

1.- Matias Romero

2.- Santa Maria Chimalapa

3.- San Juan Guichicovi

4.- Santo Domingo Petapa

5.- Santa Maria Petapa

6.- El Barrio

7.- Ciudad Ixtepec

8.- Asuncion Ixtaltepec

9.- San Miguel Chimalapa

10.- El Espinal

11.- Juchitan de Zaragoza

12.- Union Hidalgo

13.- Santo Domingo

14.- Niltepec

15.- Santo Domingo Zanatepec

16.- Santa María Xadani

17.- San Dionisio del Mar

18.- San Francisco del Mar

19.- San Francisco Ixhuatan

20.- Reforma de Pineda

21.- San Pedro Tapanatepec

22.- Chahuites

Sources: Arturo Ortiz Wadgymar, Aspects of the economy of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. Mexico, Institute of Economic Research, National Autonomous University of Mexico, 1971.

Ma. Margarita Dalton Palomo, History of Oaxaca. Textbook for the first education Volume II. Mexico, Center of Sociology, Sociological Research of the Benito Juárez Autonomous University of Oaxaca, 1980.

Some aspects of the economic and social history of the isthmus

Due to its physical characteristics, the isthmus has been a communication corridor since legendary times. Many nature trails lead to it. It is therefore reasonable to conjecture that the Zapotecs from Oaxaca traveled along these routes and then the Aztecs from Mexico to conquer it; It is also valid to say that before that, other peoples found there security and a favorable position between two seas and two mountainous blocks. Burgoa¹³ compiled a series of legends referring to the origin of the inhabitants of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec; Based on them, he assumed that the inhabitants of the area were from a “Huabe nation” (sic) that arrived on the Tehuantepec coast as a result of a series of wars that they had with each other, or with other neighbors. That “nation” says the chronicler, embarked in canoes and skirted the southern sea until it found a port that offered comfort for its propagation and sustenance. Other sources mention that the Huave culture originates from Guatemala, Nicaragua or Peru.¹⁴

The recent archaeological explorations carried out by Enrique Méndez Martínez¹⁵ tried to revise the hypothesis of Father Burgoa about the arrival of the Huaves in the Tehuantepec region, whose settlement was Villa de Xalapa, later called del Marqués. Among his conclusions, Méndez assures that it is very difficult to obtain materials from the indicated site, since it is currently covered by the waters of the Benito Juárez dam. It supposes, however, that at the same time as the arrival of the Huaves, the expansion of the Zapotec culture was taking place, hence the confinement of the Huave group to the places it currently occupies. This contrasts with the affirmations of the archaeologist Forster¹⁶ who assures that the Zapotecs are the oldest occupants of the isthmus, since he found a figurine from Juchitán made during the first times of the “archaic” culture.¹⁷

We don’t know much about the human groups that passed through the Isthmus of Tehuantepec during the “archaic” or “middle culture” era, but archaeologists constantly associate “archaic” styles with those of the Olmec culture, which appears in the shores of the Gulf of Mexico.¹⁸

It is possible that at first the Zapotecs¹⁹ were on the isthmus as merchant travelers; before they settled there definitively, they lived in Teotitlán del Valle.²⁰ As a result of a Mexica invasion, they were forced to move to the south of the Oaxacan isthmus, they founded Tehuantepec –where the Zapotec king and his entire caste settled– and later Juchitán . In this area there are several large archaeological sites and others of lesser importance. Forster points out that there are two significant localities: Tonalá (possibly a Mayan center) and Guiengola, a probable Zapotec locality. The latter was a strategic center, since from there the entire Valley of Oaxaca could be controlled; It is also located in the place where the Tehuantepec river emerges. With the archaeological explorations carried out by Agustín Delgado and others²¹ in 1958, three archaeological sites were found near Juchitán: Laguna Zope, La Ladrillera and Lidchi Bigu. There, material evidence was found that correlates with the cultures of Monte Albán. The ruins of buildings indicate that this town had an advanced culture.

In those remote times the king of the Zapotecs was Cocijoeza, who subdued the entire territory from the isthmus to beyond Oaxaca thanks to a series of battles against the mixes and later against the Aztecs, who wanted control of the isthmus. A strong military defense put an end to Aztec imperial intentions. One of the legends compiled by Burgoa says that the wars between the Zapotecs and the Aztecs ended with a marriage alliance between the daughter of the Aztec king “Copo de Algodón” and Cocijoeza. From this union was born the last king of the Zapotecs, Cocijopij, who cordially welcomed Alvarado after the fall of Mexico, when he passed through his territory on his way to Guatemala. Cocijopij allowed himself to be persuaded, recognized the King of Spain as his sovereign and was baptized along with all his court; He continued to reign in his lordship for a while until, accused of falling back into “paganism” for worshiping a stone, he was stripped of his hierarchy.

In pre-Hispanic times, the communities were organized in small villages that surrounded a larger town; in it the most important activities were carried out, and, due to this organization, each inhabitant had “his own lot given by the neighborhood society.”²² Very little else is known about Zapotec social organization, except that it was basically formed by priests, caciques or cacicas, main or noble ladies and gentlemen and the common people or comuneros, that is to say, it was a theocratic system.

The economy of the pre-Hispanic Zapotecs was based mainly on agriculture, hunting, the breeding of various animals, and fishing; activities that they practiced even from the period described by archaeologists as “Preclassic or Formative of Mesoamerica”.²³ With the arrival of the conquistadors, the Zapotecs found themselves subjugated and forced to transform their economic and social life.

In colonial times, the eight Marquesan haciendas – which for a long time were part of the Hernán Cortés family – were managed by Oaxacan tenants; four of these were administered by the Dominican friars on the isthmus, with their economy linked to Antequera –the main administrative and commercial center of the south–. These haciendas “were in charge of supplying meat and other animal products to the urban Spaniards”, and had staff descendants of African slaves who later reached the category of “free mulattoes”.²⁴

In his study on the indigenous rebellions in Tehuantepec, John Tutino mentions that in the entire period from 1560 to 1740, the majority of the inhabitants had enough land for subsistence cultivation and complemented their economy with the production of handicrafts and trade. between the different towns of the region.

At that time, the ones who had the most land were the caciques, and in general “the lands were worked communally to pay tributes to the Crown, which was later entrusted to the church”;²⁵ due to this, various struggles of the Zapotecs to live in units took place. independent policies. However, almost all the uprisings were brutally suppressed. The manner and circumstances in which the rebels of Tehuantepec, Nejapa, Ixtepeji and Villa Alta were punished were possibly the cruelest that occurred in colonial times.

At that stage the isthmus was of great importance, since in the South Lagoons the shipyards built since 1526 were used; large gold deposits were also exploited; the product was traded in powder form or transformed into handicrafts; in addition, enormous quantities of salt were exported.²⁶ In the mid-18th century, large-scale exploitation of cochineal and indigo for export was introduced, and with this came more Spanish population.²⁷

National independence led to a series of changes; the trade in dyes and the life of the isthmus entered a different stage. A new elite made up of French, German and Italian dominated the cochineal and indigo trade (1830-1840); they also acquired “control of the main cattle, sugar and indigo plantations of Tehuantepec”.²⁸

After Independence, economic incursions that threatened the control of resources by indigenous communities caused a climate of tension that lasted until the mid-19th century. When the state of Oaxaca was created (1825), the Zapotecs of Juchitán – who until then traded fabrics and salts with Guatemala – were dispossessed of their salt flats and farmland. They were later recovered, at a time when the country was repelling the American invader. After the war between Mexico and the United States with the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848), the North Americans were offered the right of passage through the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, which Santa Anna ratified with the treaty of La Mesilla; in this permission was granted to build a land road and a trans-isthmian railway. Then they continued a series of projects in this regard (1857-859) that were never carried out.

In 1850 the then governor of the state of Oaxaca, Benito Juárez, sent an expedition to repress the rebels who were fighting for control of its resources, after which, says John Tutino, a new municipal council was installed, made up of men loyal to the government and to the interests of the merchants of the city of Oaxaca.

When the French arrived to invade the country (1866), the Juchitecs prevented the advance of the invading troops towards Guatemala. Once the conflict ended, the Juchitecos continued to claim their communal lands (1868). Benito Juárez, now as President of the Republic, ruled in favor of the people.

By the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, the economic changes of the Porfirian regime influenced the isthmus in such a way that the entry of American and English investments resulted in the creation of numerous non-agricultural activities. At this time the transisthmian communication projects could be carried out. In practice, the construction of the Tehuantepec railroad (1894-1899) served international trade, thanks to the combination of the ports of Salina Cruz and Coatzacoalcos. The railway led many foreign families to settle on the isthmus and, in addition, new activities that required a lot of manual labor began to be covered from the countryside to the city. The “golden age” –as it was called– declined with the opening of the Panama Canal (1915). Meanwhile, economic modifications were coupled with constant rebellions and political struggles.

In recent years (between 1946 and 1955) the trans-isthmian highway – a fast communication route between the two oceans – and the Pan-American highway, which connects Tehuantepec with Oaxaca and Guatemala, were built;²⁹ reconstruction works were also carried out in the ports of Coatzacoalcos and Salina Cruz, and warehouses and docks were built.

During those years the agrarian problems continued to worsen; By 1961, the year in which the Benito Juárez Dam was inaugurated in “Irrigation District # 19” (a work financed by the Inter-American Development Bank), the agrarian problem became a crisis “until it reached rebellious proportions, with threats to separate the isthmus of the State and of the country”.³⁰ After two years, the istmeños were convinced to accept the ejido regime, after the State recognized property of communal origin; finally the corresponding titles were extended and the small property and the common lands were created.

In 1964 President López Mateos recognized and titled the communal property of Juchitán and surrounding towns; The local bourgeoisie, monopolizing the land and the salt flats, then formed a committee of “small landowners” with advice and support from the federal government. The same policy was endorsed by Díaz Ordaz and in 1966 certificates of inalienability were issued to the hoarders of large portions of land.³¹ In the following years, the agrarian struggles were reduced to the battle for the seizure of municipal power. For example, in 1968 the Juchiteco Civic Committee “Heroes of September 5” faced the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) for the first time in municipal elections.

The current outbreaks of discontent at the “political level” are related to unfair state development projects designed on the basis of private capital and foreign investment. As an example, we can cite the ALFA OMEGA project (1983-1988)³² –which now functions in a rudimentary fashion–, which aims to unite two development poles in a transoceanic highway: Coatzacoalcos and Salina Cruz, industrial and commercial ports with their respective parks or corridors. The construction of these industrial corridors, along the railway, has led to the dispossession of communal lands, among other unfair actions.

The Oaxacan isthmus suffers from problems that are related, on the one hand, to ancient interoceanic communication projects, and on the other, to disputes between the various types of land tenure, a situation that has worsened especially in recent decades.

It must be added that the sequence of contemporary history has focused almost fundamentally on the city of Juchitán, since for a long time this has been the most important political, cultural, and commercial center in the area; It is no coincidence, then, that many of the Juchitec rebellions had their headquarters in that city, without exception to those of today.

Current socioeconomic organization

In the Oaxacan isthmus, the population is concentrated mostly in the cities and a smaller number in the countryside.

Part of the inhabitants of this area work in the following sources: the cement factory in Lagunas; the repairer and builder of railway cars in Matías Romero; electric power plants; soft drink and beer bottlers; the Dry Dock; the big companies of Pemex; the freezing plant in Salina Cruz; the small industries on the Pan-American highway; the Ixtepec airport; the four pumping stations located between Loma Larga, Medias Aguas and Donají, and the commerce and services of the important cities. Despite their existence, they are insufficient, even to provide work for hundreds of people who finish their specialized training. This type of education is obtained at the Industrial and Commercial Technical School of Juchitán and at the recently created Regional Technological Institute of Oaxaca.

Faced with the few sources of work, people with or without specialization, not having a piece of land either, emigrate to the oil centers of Minatitlán and Coatzacoalcos, or to any other city.

Other forms of work that provide sustenance to the inhabitants of the isthmus are the occasional trades of masonry, making party dresses -with embroidery done by hand or with a sewing machine- mechanics and other backyard trades. However, the fundamental basis of subsistence in the Oaxacan isthmus is agricultural, fishing, livestock and artisanal production.

Most of the peasants work rainfed land and normally harvest the products that allow them family self-sufficiency. The products that are sown the most are: corn, beans and sesame.

The “nortes” represent a strong obstacle to agriculture, and to date no better seeds have been introduced; for example, low-yield and short-grown native corn prevails, since it is the only one that resists the strong “nortes”.³³

Often peasant families plant fruit trees such as mango, papaya, plum, tamarind, guava, soursop, and grow small amounts of coconut, coffee, tobacco, vegetables, and flowers. Sugar is a product implemented at the industry level in the López Portillo mill.

The sowing technique –until the middle of this century– was that of the “talapié”, which consisted of loosening the earth with the coa; the holes were sown and the seed was covered with the foot. With this procedure, it was necessary to do several weedings and put “ears” (piles of earth) to protect the plants from the strong winds that blow in the area.³⁴ Subsequently, the “talapié” system was largely replaced by the use of the oxen team, which consists of a wooden or metal plow, puya –a long stick with a point, used to carry the team– and the yoke with which the depth of the plow is calculated.³⁵

In reality, many of the peasants feel reluctant to pay credits for the use of tractors, fertilizer and insecticide, since the chances of recovery are almost nil and they fear -with justifiable reason- losing their lands.

As the sowings are generally done in April and the harvests in the months of October to February, the rest of the year the peasants seek their livelihood elsewhere, engaging in activities such as goldsmithing, making flower arrangements and various jobs.

Livestock is poor and is hardly technical. Cattle, horses, goats (with many diseases and pests) are raised and most families have pigs and chickens.

Another important percentage of the population works in the salt flats in the form of a cooperative. In the nearby lagoons, fish, shrimp, shrimp, turtles and the eggs of that animal are obtained. Like the farmer, the fisherman is hampered in his work by variations in the weather.

Hunting, gathering and forestry are activities that provide work for the isthmians, but are not very important in relation to handicrafts.

In the Oaxacan isthmus, as in other areas of the country, the family fulfills economic and social functions and its own elementary division of labor reigns within it; only that there the Zapotec woman is a seller and processor of what the man produces. The difference here, in comparison with other societies, is that the woman is not only a seller of homemade products, but the trade that she dominates represents a highly important income for the family. This has come to confuse many scholars, who have believed they found evident vestiges of matriarchy.

aWhatever the circumstances around the development of the Zapotec woman as a merchant –Royce tells us–, it is not a phenomenon of poor families, but this extends to the “upper class” or bourgeoisie.³⁶

Many of the proletarian families of the isthmus face day by day the general inflation that afflicts the entire country. Despite how difficult this situation is, the majority of the Istmeños have a great spirit of cooperation and solidarity, which is actually the basis that has always saved and solved many of their economic problems. This mutualist spirit, which follows the principle of help among relatives, is known in anthropological literature as tequio (from the Nahuatl word tequitl), which means tribute or work without any remuneration to carry out works for the benefit of the community, such as construction. houses and parties.³⁷

Among the Zapotecs of the Valley, this last type of custom is known as guelaguetza or guelalezaa and in the Oaxacan isthmus as guendalizaa,³⁸ a tradition of indisputable pre-Hispanic origin that is clearly manifested in the mayordomia festivities called candles. In the past there was also a type of cooperation for marriage festivities called guendaroyaa, that is, the contribution of gifts such as live animals (cattle, pigs, sheep, poultry), a sack of corn and condiments essential for cooking;³⁹ in part this it continues to get used to, but it is no longer so widespread.

The mutual spirit manifests itself in many ways. One more form, which takes the form of monetary aid, “alms”, gifts or reciprocal compensation in kind (bread, chocolate and other drinks) is called guna or xindxaa,⁴⁰ and is granted in all festive or mourning acts.

The stewardship parties

In the majority of collective work, simple social contact engenders, among other things, a special excitement that favors the individual capacity for performance; That is why for the Zapotec population of the isthmus, as for almost all peasant communities, the festival –as a collective work that it is– is a relevant event. In addition to the previous meanings, the party is a symbol of prestige: whoever has more money throws more parties, thereby gaining more prestige and the possibility of having greater political influence; although in reality it is very common for even the poorest to make a candle to demonstrate, among other things, and as they say, “that they are as equal as those who have money”.

Almost all the Isthmus festivities are ostentatious thanks to the fact that people collaborate with their guna or xindxaa or with the guendalizaa. Little by little, however, the capitalist spirit has infiltrated regional traditions. For example, in large parties it is customary to have a “bower”, which serves to protect yourself from the sun or rain; the traditional “enramada” consists of a roof made of green reeds, wood and palm and banana leaves, supported by large posts embedded in the ground, and many men participate with their unpaid work for its construction; However, currently the breweries, with the intention of selling, provide their plant of piecework workers, who place large sheets as a “borer”; also now people prefer to use a heavy cloth tarpaulin because it is more practical and less labor intensive.

The innumerable mutual societies of the different neighborhoods keep the Zapotec community strongly united, which, with their contributions and common effort, make the celebration of their festivities possible. No one is forced to belong to these groups, although the same social pressure induces everyone to participate.

The objectives of the semi-religious societies of the isthmus are to organize the annual festivities called candles, carry out activities of a social, cultural, sports and mutual aid nature, but without any profit motive.⁴¹ The expenses involved in carrying out the activities are covered with the ordinary or extraordinary fees that the partners contribute, or with the income that the companies obtain, for example through raffles or cinema shows. These companies are managed and represented by a board of directors made up of a president, a vice-president, a secretary, a treasurer and a variable number of members. The person who presides over this type of society and bears part of the cost of a candle is called a butler. The oldest members who help him are called guzanagolas and each one of the women who make up these “sisterhoods” are named guzanas.⁴² In addition, there are other charges associated with some candles that are held in the month of May in Juchitán, when carries out the Fruit Throw or Carreta guié (flower treat)⁴³ which must be presided over by a captain and a female captain, always sons of the guzanas.⁴⁴

The board of directors has among its main functions: directing the annual activities of the company; designate auxiliary commissions; intervene in the annual delivery of the company’s assets made by the outgoing mayordomo under strict inventory, and hire the services of the musicians who entertain the dances.

The most important social event of these groups is the candle, a festival that is celebrated annually. On that occasion, the directors must hire an orchestra or a band, in addition to taking charge of the entire organization of the party.

There are various and conflicting versions about why a series of isthmus festivities are called candles. A popular version tells us that the name candle is probably due to the fact that the next day of that celebration, the women bring huge candles to the church, as a religious offering; another of the same origin affirms that it is called that because the party “watches” all night. According to Samuel Villalobos⁴⁵ the name vela is given to festivities of religious origin similar to those celebrated in Catalonia, Spain, which generally agree with the “holder” saint of the town and which take place under large canvas veils, called “envelats” there. “.

Possibly the ancient Zapotecs, before the Catholic religious norms were imposed on them, worshiped deities related to the fertility of the earth and nature in their festivals –with their ritual calendar of 260 days. Then the Spanish religious looked for a way to appropriate these popular manifestations to catechize. The foregoing seems to be confirmed by the fact that there are still some candles –the name probably given to them by Catholic priests– which are called gue’labeeñe (lizard candle), biadxi candle (plum candle); and candles (with an additional symbolic name), under which people are grouped according to the nature of the work, often of a family nature. It is very probable that over time the popular festivals dedicated to nature were given the name of candles; then the names of the Catholic titular saints were added and, later, the “remarkable” surnames (as an example we have the López candle or the Pineda candle that are made in Juchitan).

The village festivals or candles, which now have no meaning other than simple coexistence, take place not only in May, but also in August, September and October. In addition, the Juchiteco people celebrate other festivals on the Catholic calendar.

Life and death ceremonies

There are fabulous stories that have to do with the guendabee or totem of people when they are born,” Don Eustaquio told me,⁴⁶ and added that some old men told him of a custom: spreading sand next to the bed of the woman in labor to see what animal was approached there, this would then be the “totem” of the creature or guendabee. If the boy or girl got sick, a commission was in charge of looking for his totem and then they cured him so that the creature would heal. “Now they don’t believe in that anymore “, he claimed.

Don Victoriano López informed me that 40 days after a birth it was customary for a band, trio or whatever you wanted to play and depending on the money available, for five hours. Among the sounds in the mandatory repertoire were: “I see, I see Santa Rosa”, baduhuini (little creature) and cayale guié (the flower is opening).⁴⁷ Several interviewed musicians agree that parties are no longer held for such an occasion, unless the mother is new.

At present, the ceremonies that are performed during the growth of a boy or girl are the same that are observed throughout Catholic Mexico: they are baptized and parties are held after having chosen the godmother and godfather. If the child dies, the godparents are the first to receive the news, and they are the ones in charge of buying the “ropón” for the child. If the parents die, the child becomes part of the family of the godparents, who will treat it as a legitimate child. The godparents are also the ones in charge of confirming or blessing the name of the godchild and it is also always expected that the godparents at the baptism are the godparents at the wedding.

Regarding the education of children, it should be said that from their birth, until approximately five years of age, they enjoy full family protection. Then, the infants begin to work on complementary activities for family subsistence, first in the form of children’s games such as hunting small animals or fetching water from the well. Subsequently, work becomes –according to sociologists– “formal” in the case of men (sowing, weeding and harvesting, etc.) and “informal” in the case of women (housework).

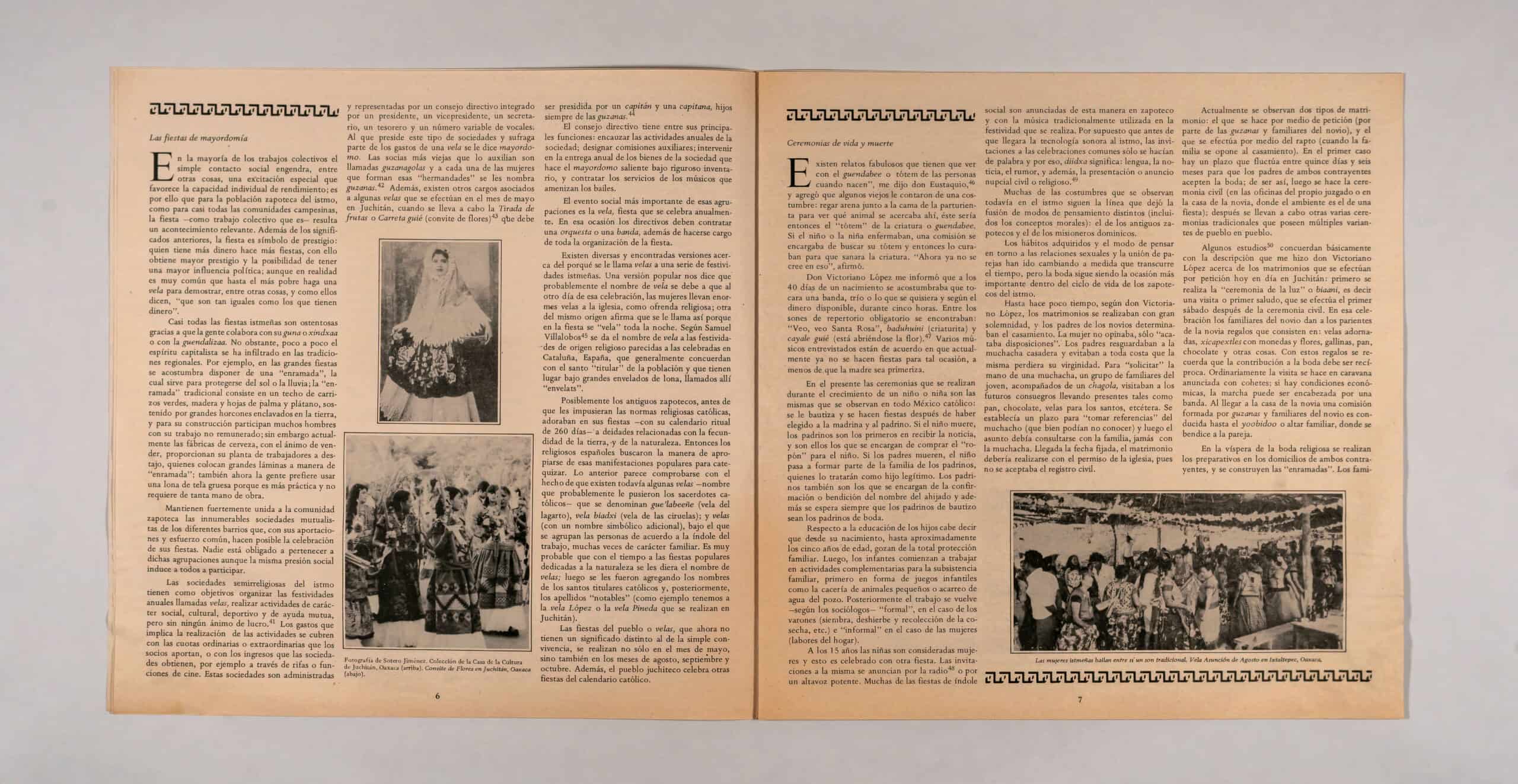

At the age of 15, girls are considered women and this is celebrated with another party. Invitations to it are announced over the radio⁴⁸ or over a loud speaker. Many of the festivities of a social nature are announced in this way in Zapotec and with the music traditionally used in the festivity that takes place. Of course, before the arrival of sound technology to the isthmus, invitations to common celebrations were only made by word of mouth and for this reason, diidxa means: language, news, rumor, and also, civil or religious nuptial presentation or announcement. .⁴⁹

Many of the customs that are still observed on the isthmus follow the line left by the fusion of different modes of thought (including moral concepts): that of the ancient Zapotecs and that of the Dominican missionaries.

The habits acquired and the way of thinking about sexual relations and the union of couples have changed as time goes by, but the wedding continues to be the most important occasion in the life cycle of the Zapotecs of the isthmus.

Until recently, according to Don Victoriano López, marriages were performed with great solemnity, and the parents of the bride and groom determined the marriage. The woman did not have an opinion, she only “accepted provisions.” The parents protected the marriageable girl and prevented her from losing her virginity at all costs. To “request” the hand of a girl, a group of the young man’s relatives, accompanied by a chagola, would visit the future in-laws bringing presents such as bread, chocolate, candles for the saints, etc. A deadline was established to “take references” from the boy (which they might well not know) and then the matter had to be consulted with the family, never with the girl. When the set date arrived, the marriage should take place with the permission of the church, since civil registration was not accepted.

Two types of marriage are currently observed: the one that is made by petition (by the groom’s worms and relatives), and the one that is carried out by means of kidnapping (when the family opposes the marriage). In the first case, there is a term that fluctuates between fifteen days and six months for the parents of both parties to accept the wedding; if so, then the civil ceremony is held (in the offices of the court itself or in the bride’s house, where the atmosphere is that of a party); Afterwards, several other traditional ceremonies are carried out that have multiple variants from town to town.

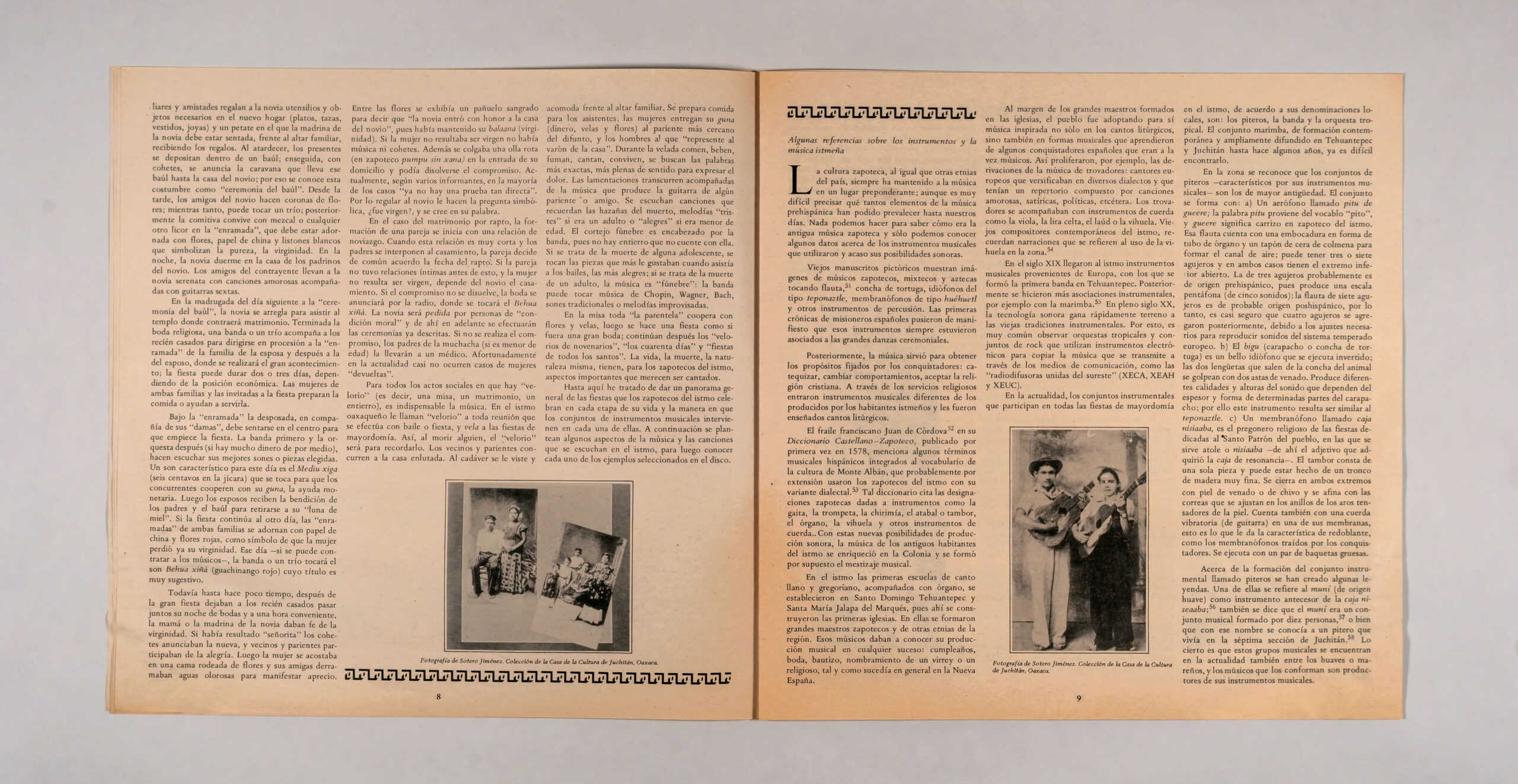

Some studies⁵⁰ basically agree with the description that Don Victoriano López gave me about the marriages that are carried out by request today in Juchitán: first the “ceremony of light” or biaani is performed, that is, a visit or first greeting, which It takes place on the first Saturday after the civil ceremony. In this celebration, the relatives of the groom give the relatives of the bride gifts consisting of: decorated candles, xicapextles with coins and flowers, chickens, bread, chocolate and other things. With these gifts it is remembered that the contribution to the wedding must be reciprocal. Ordinarily the visit is made in a caravan announced with rockets; if there are economic conditions, the march can be led by a band. Upon arriving at the bride’s house, a commission made up of guzanas and relatives of the groom is led to the yoobidoo or family altar, where the couple is blessed.

On the eve of the religious wedding, preparations are made in the homes of both parties, and the “arbors” are built. Relatives and friends give the bride utensils and objects necessary in the new home (plates, cups, dresses, jewelry) and a petate in which the bride’s godmother must sit, in front of the family altar, receiving the gifts. At sunset, the presents are deposited inside a trunk; Immediately, with rockets, the caravan that takes that trunk to the groom’s house is announced; that is why this custom is known as the “trunk ceremony”. Starting in the afternoon, the groom’s friends make flower crowns; meanwhile, you can play a trio; later the procession coexists with mezcal or any other liquor in the “enramada”, which must be adorned with flowers, tissue paper and white ribbons that symbolize purity, virginity. At night, the bride sleeps at the home of the groom’s godparents. The bride and groom’s friends serenade the bride with love songs accompanied by sixth guitars.

In the early morning of the day after the “trunk ceremony”, the bride prepares to attend the temple where she will be married. After the religious wedding, a band or a trio accompanies the newlyweds to go in procession to the “arbor” of the wife’s family and then to the husband’s, where the great event will take place; the party can last two or three days, depending on the economic position. The women of both families and those invited to the party prepare the food or help serve it.

Under the “enramada” the bride, in the company of her “ladies”, must sit in the center for the party to begin. The band first and the orchestra later (if there is a lot of money involved), play their best sones or chosen pieces. A characteristic son for this day is the Mediu xiga (six cents in the gourd) that is played so that the attendees cooperate with their guna, the monetary aid. Then the spouses receive the blessing of the parents and the trunk to retire to their “honeymoon”. If the party continues the next day, the “arbors” of both families are decorated with tissue paper and red flowers, as a symbol that the woman has already lost her virginity. That day –if the musicians can be hired–, the band or a trio will play the son Behua xiñá (red snapper) whose title is very suggestive.

Still, until recently, after the big party they let the newlyweds spend their wedding night together and at a convenient time. the bride’s mother or godmother attested to her virginity. If it had been “miss” the rockets announced the news, and neighbors and relatives participated in the joy. Then the woman would lie on a bed surrounded by flowers and her friends would pour scented water to show appreciation.

A bloody handkerchief was displayed among the flowers to say that “the bride entered the groom’s house with honor”, as she had kept her balaana (virginity). If the woman did not turn out to be a virgin there was no music or rockets. In addition, a broken pot (in Zapotec pumpu without xana) was hung at the entrance of his home and the commitment could be dissolved. Currently, according to several informants, in most cases “there is no longer such a direct test.” Usually the groom is asked the symbolic question, was he a virgin?, and he believes his word.

In the case of marriage by kidnapping, the formation of a couple begins with a dating relationship. When this relationship is very short and the parents get in the way of the marriage, the couple agrees on the date of the abduction. If the couple did not have intimate relations before this, and the woman does not turn out to be a virgin, the marriage depends on the groom. If the commitment is not dissolved, the wedding will be announced on the radio, where the Behua xiñá will be played. The bride will be requested by people of “moral condition” from then on the ceremonies already described will be carried out. If the commitment is not made, the girl’s parents (if she is a minor) will take her to a doctor. Fortunately, nowadays there are almost no cases of “returned” women.

For all social acts in which there is a “wake” (that is, a mass, a marriage, a burial), music is essential. In the Oaxacan isthmus they call “wakes” any gathering that takes place with a dance or party, and a wake at stewardship parties. Thus, when someone dies, the “wake” will be to remember him. Neighbors and relatives go to the house in mourning. The corpse is dressed and accommodated in front of the family altar. Food is prepared for attendees; the women give their guna (money, candles and flowers) to the closest relative of the deceased, and the men to the one who “represents the man of the house”. During the evening they eat, drink, smoke, sing, live together, looking for the most exact words, the most meaningful to express the pain. The lamentations take place accompanied by the music produced by the guitar of a relative or friend. Songs are heard that recall the feats of the dead, “sad” melodies if he was an adult or “happy” if he was a minor. The funeral procession is headed by the band, since there is no burial that does not have it. If it is about the death of an adolescent, the pieces that she liked the most when she attended the dances are played, the most joyful; if it is the death of an adult, the music is “funeral”: the band can play music by Chopin, Wagner, Bach, traditional sounds or improvised melodies.

In the mass all “the relatives” cooperate with flowers and candles, then a party is held as if it were a great wedding; the “novena wakes”, “the forty days” and “all saints’ festivities” continue afterwards. Life, death, nature itself, have, for the Zapotecs of the isthmus, important aspects that deserve to be sung.

So far I have tried to give an overview of the festivities that the Zapotecs of the isthmus celebrate at each stage of their lives and the way in which the ensembles of musical instruments intervene in each of them. Below are some aspects of the music and songs heard on the isthmus, to later learn about each of the selected examples on the disc.

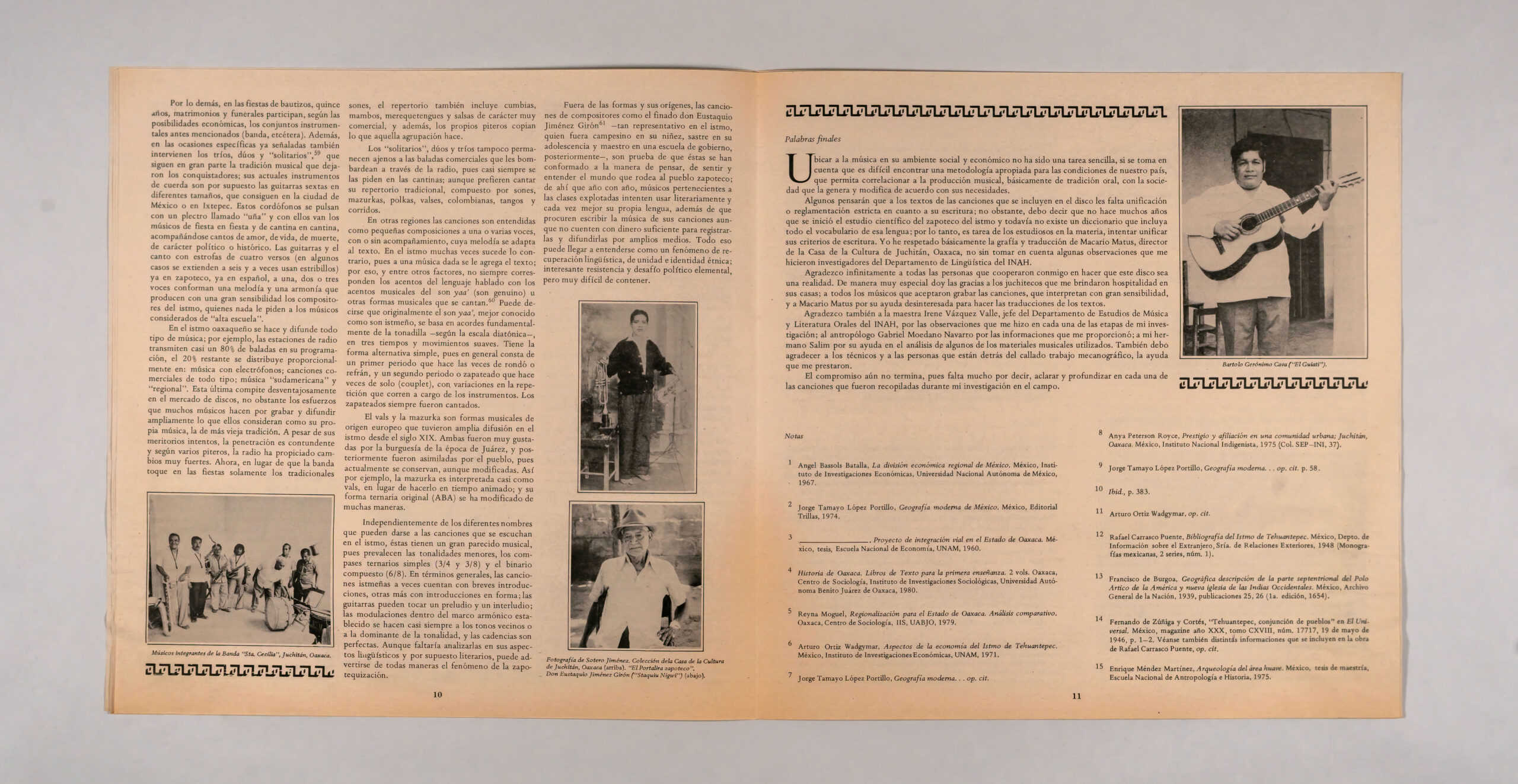

Some references about the instruments and istmeña music

The Zapotec culture, like other ethnic groups in the country, has always kept music in a prominent place; although it is very difficult to specify how many elements of pre-Hispanic music have been able to prevail to this day. We can do nothing to know what ancient Zapotec music was like and we can only know some information about the musical instruments they used and perhaps their sound possibilities.

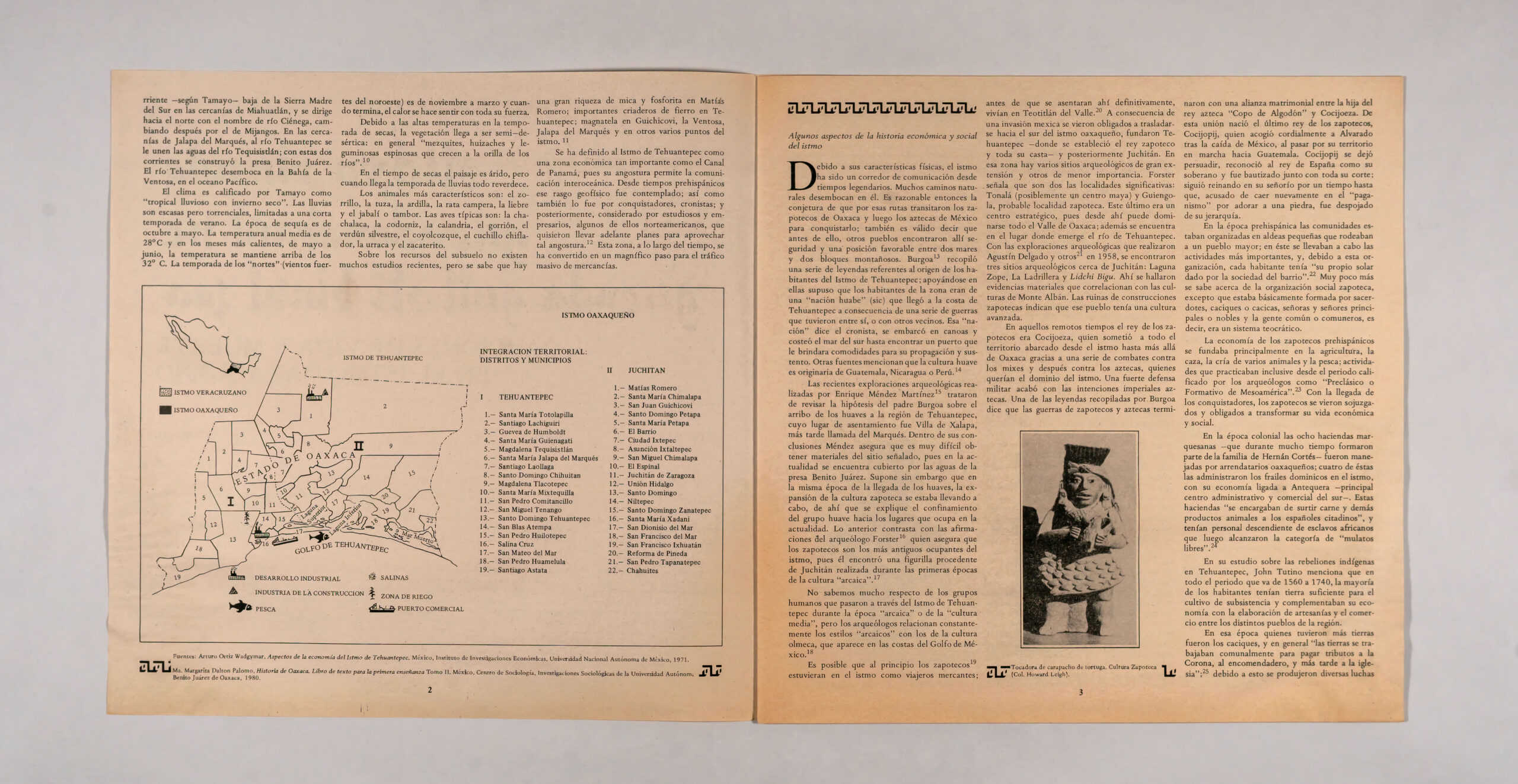

Old pictorial manuscripts show images of Zapotec, Mixtec, and Aztec musicians playing flute,⁵¹ tortoise shell, Teponaztle-type idiophones, Huehuetl-type membranophones, and other percussion instruments. The first chronicles of Spanish missionaries revealed that these instruments were always associated with great ceremonial dances.

Subsequently, music served to achieve the purposes set by the conquerors: catechize, change behavior, accept the Christian religion. Through religious services, musical instruments different from those produced by the isthmian inhabitants entered and they were taught liturgical songs.

The Franciscan friar Juan de Córdova⁵² in his Diccionario Castellano-Zapoteco, published for the first time in 1578, mentions some Hispanic musical terms integrated into the vocabulary of the Monte Albán culture, which probably by extension were used by the Zapotecs of the isthmus with their dialectal variant.⁵³ Such a dictionary cites the Zapotec designations given to instruments such as the bagpipe, the trumpet, the shawm, the tabal or drum, the organ, the vihuela, and other stringed instruments. With these new possibilities of sound production, the music of the ancient inhabitants of the isthmus was enriched in the Colony and, of course, musical miscegenation was formed.

On the isthmus, the first schools of plain and Gregorian chant, accompanied by the organ, were established in Santo Domingo Tehuantepec and Santa María Jalapa del Marqués, since the first churches were built there. In them, great Zapotec teachers and other ethnic groups of the region were trained. These musicians publicized their musical production at any event: birthdays, weddings, baptisms, the appointment of a viceroy or a religious, as was generally the case in New Spain.

Apart from the great teachers trained in the churches, the people gradually adopted music inspired not only by liturgical songs, but also by musical forms that they learned from some Spanish conquistadors who were also musicians. Thus, for example, the derivations of the music of troubadours proliferated: European singers who performed in various dialects and who had a repertoire made up of love, satirical, political songs, etc. The troubadours accompanied themselves with string instruments such as the viola, the Celtic lyre, the lute or the vihuela. Old contemporary composers from the isthmus recall stories that refer to the use of the vihuela in the area.⁵⁴

In the 19th century, musical instruments from Europe arrived on the isthmus, with which the first band was formed in Tehuantepec. Later, more instrumental associations were made, for example with the marimba.⁵⁵ In the middle of the 20th century, sound technology was rapidly gaining ground on the old instrumental traditions. For this reason, it is very common to observe tropical orchestras and rock groups that use electronic instruments to copy the music that is transmitted through the media, such as the “United Radio Stations of the Southeast” (XECA, XEAH and XEUC).

At present, the instrumental ensembles that participate in all the mayordomía festivities in the isthmus, according to their local denominations, are: the piteros, the band and the tropical orchestra. The marimba ensemble, of contemporary formation and widely spread in Tehuantepec and Juchitán until a few years ago, is already difficult to find.

In the area it is recognized that the sets of piteros –characteristic for their musical instruments– are the oldest. The group is formed with: a) An aerophone called pitu de gueere; The word pitu comes from the word “pito”, and gueere means reed in Zapotec from the isthmus. This flute has an organ pipe-shaped mouthpiece and a beehive wax stopper to form the air channel; it can have three or seven holes and in both cases they have the lower end open. The one with three holes is probably of pre-Hispanic origin, since it produces a pentaphone scale (with five sounds); The seven-hole flute is of probable post-Hispanic origin, therefore it is almost certain that four holes were added later, due to the necessary adjustments to reproduce sounds of the European tempered system. b) The bigu (carapace or turtle shell) is a beautiful idiophone that is executed inverted; the two tabs that come out of the animal’s shell are struck with two deer antlers. It produces different qualities and heights of sound that depend on the thickness and shape of certain parts of the carapace; for this reason this instrument turns out to be similar to the teponaztle. c) A membranophone called a nisiaaba box, is the religious preacher of the festivals dedicated to the Patron Saint of the town, in which atole or nisiaaba is served – hence the adjective that the resonance box acquired. The drum consists of a single piece and can be made from a very thin log of wood. It closes at both ends with deer or goat skin and is refined with the straps that are adjusted in the rings of the leather tightening rings. It also has a vibrating string (guitar) in one of its membranes, this is what gives it the snare characteristic, like the membranophones brought by the conquerors. It is played with a pair of thick drumsticks.

Some legends have been created about the formation of the instrumental group called piteros. One of them refers to the muní (of Huave origin) as the predecessor instrument of the niseaaba box;⁵⁶ it is also said that the muní was a musical ensemble made up of ten people,⁵⁷ or that a pitero who lived in the seventh section of Juchitán.⁵⁸ The truth is that these musical groups are currently also found among the Huaves or Mareños, and the musicians that make them up are producers of their musical instruments.

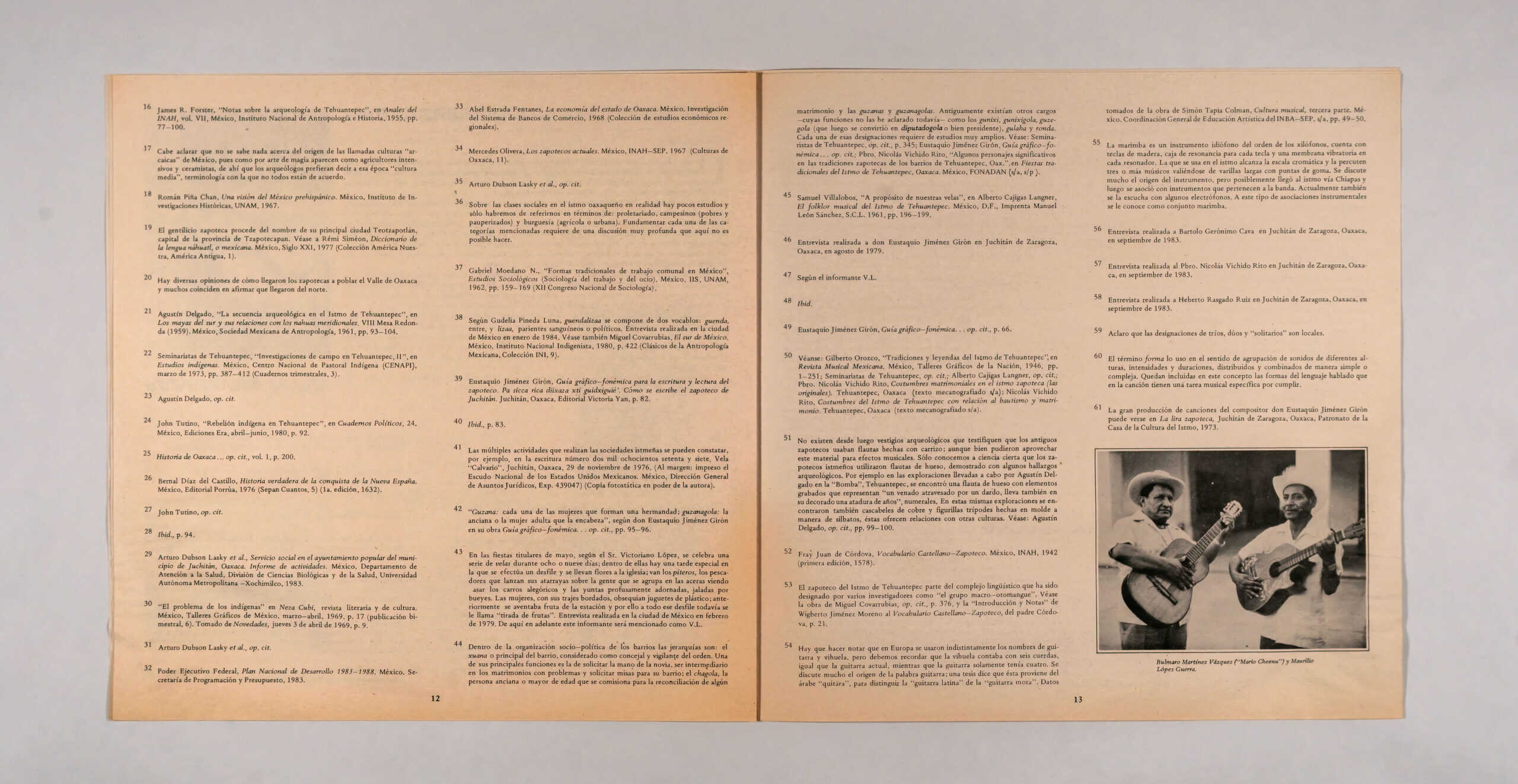

For the rest, in the festivities of baptisms, fifteen years, marriages and funerals, the aforementioned instrumental ensembles (band, etc.) participate, according to economic possibilities. In addition, on the specific occasions already indicated, trios, duets and “solitarios” also intervene,⁵⁹ and which largely follow the musical tradition left by the conquerors; their current string instruments are of course the sixth guitars in different sizes, which They are found in Mexico City or Ixtepec. These chordophones are struck with a plectrum called “uña” and the musicians go with them from party to party and from bar to bar, accompanying each other songs of love, life, death, character political or historical.The guitars and the singing with stanzas of four verses (in some cases they extend to six and sometimes use refrains) already in Zapotec, already in Spanish, to one, two or three voices make up a melody and a harmony that produce with a great sensitivity the composers of the isthmus, who ask nothing of the musicians considered “high school”.

In the Oaxacan isthmus, all kinds of music are made and disseminated; For example, radio stations broadcast almost 80% of ballads in their programming, the remaining 20% is proportionally distributed in: music with electrophones; commercial songs of all kinds; “South American” music and “regional” sica. The latter competes disadvantageously in the record market, despite the efforts that many musicians make to record and widely disseminate what they consider to be their own music, that of the oldest tradition. Despite of their meritorious attempts, the penetration is forceful and according to several piteros, the radio has brought about very strong changes Now, instead of the band playing only the traditional sones at parties, the repertoire also includes cumbias, mambos, merequetengues and salsas of a very commercial nature, and also, the piteros themselves copy what that group does.

The “loners”, duets and trios are not immune to the commercial ballads that bombard them on the radio, since they are almost always asked for in canteens; although they prefer to sing their traditional repertoire, made up of sones, mazurkas, polkas, waltzes, Colombianas, tangos and corridos.

In other regions, songs are understood as small compositions for one or more voices, with or without accompaniment, whose melody is adapted to the text. On the isthmus the opposite often happens, since the text is added to a given piece of music; for this reason, and among other factors, the accents of the spoken language do not always correspond to the musical accents of the son yaa’ (they are genuine) or other musical forms that are sung.⁶⁰ It can be said that originally the son yaa’, better known as son istmeño, is based on chords fundamentally from the tonadilla -according to the diatonic scale-, in three times and soft movements. It has the simple alternative form, since in general it consists of a first period that acts as a rondo or refrain, and a second period or zapateado that acts as a solo (couplet), with variations in repetition that are carried out by the instruments. . The zapateados were always sung.

The waltz and the mazurka are musical forms of European origin that were widely distributed in the isthmus since the 19th century. Both were very liked by the bourgeoisie of the time of Juárez, and later they were assimilated by the people, since they are currently preserved, although modified. Thus, for example, the mazurka is interpreted almost like a waltz, instead of doing it in animated time; and its original ternary form (ABA) has been modified in many ways.

Regardless of the different names that can be given to the songs that are heard on the isthmus, they have a great musical resemblance, since minor tonalities prevail, simple ternary measures (3/4 and 3/8) and compound binary (6 /8). In general terms, the isthmian songs sometimes have brief introductions, others more with formal introductions; the guitars can play a prelude and an interlude; the modulations within the established harmonic framework are almost always done to the neighboring tones or to the dominant of the tonality, and the cadences are perfect. Although it would be necessary to analyze them in their linguistic and, of course, literary aspects, the phenomenon of Zapotecization can still be noted.

Apart from the forms and their origins, the songs of composers such as the late Don Eustaquio and Jiménez Girón⁶¹ –so representative in the isthmus, who was a peasant in his childhood, a tailor in his adolescence and a teacher in a government school, later–, are proof that they have conformed to the way of thinking, of feeling and understanding the world that surrounds the Zapotec people; Hence, year after year, musicians belonging to the exploited classes try to use their own language literaryly and increasingly better, in addition to trying to write the music for their songs even though they do not have enough money to register and disseminate them through wide media. All this can be understood as a phenomenon of linguistic recovery, unity and ethnic identity; interesting resistance and elemental political challenge, but very difficult to contain.

Final words

Locating music in its social and economic environment has not been an easy task, if one takes into account that it is difficult to find an appropriate methodology for the conditions of our country, which allows to correlate musical production, basically from oral tradition, with the society that generates and modifies it according to its needs.

Some will think that the texts of the songs that are included in the disc lack unification or strict regulations regarding their writing; However, I must say that not many years ago the scientific study of Isthmus Zapotec began and there is still no dictionary that includes all the vocabulary of that language; therefore, it is the task of scholars in the field to try to unify their writing criteria. I have basically respected the spelling and translation of Macario Matus, director of the House of Culture of Juchitán, Oaxaca, not without taking into account some observations made to me by researchers from the Department of Linguistics of the INAH.

I am infinitely grateful to all the people who cooperated with me in making this record a reality. In a very special way I thank the Juchitecos who offered me hospitality in their homes; to all the musicians who agreed to record the songs, which they interpret with great sensitivity, and to Macario Matus for his disinterested help in translating the texts.

I also thank Professor Irene Vázquez Valle, head of the INAH Department of Oral Music and Literature Studies, for the observations she made to me in each of the stages of my research; to the anthropologist Gabriel Moedano Navarro for the information he provided me; to my brother Salim for his help in analyzing some of the musical material used. I must also thank the technicians and the people behind the quiet typing work for the help they gave me.

The commitment is not over yet, since there is still a lot to say, clarify and delve into each of the songs that were compiled during my research in the field.

Notes

¹ Ángel Bassols Batalla, La división económica regional de México. México, Instituto de Investigaciones Económicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1967.

² Jorge Tamayo López Portillo, Geografía moderna de México, México, Editorial Trillas, 1974.

³ _________________. Proyecto de integración vial en el Estado de Oaxaca. México, tesis, Escuela Nacional de Economía, UNAM, 1960.

⁴ Historia de Oaxaca. Libros de Texto para la primera enseñanza. 2 vols. Oaxaca, Centro de Sociología, Instituto de Investigaciones Sociológicas, Universidad Autónoma Benito Juárez de Oaxaca, 1980.

⁵ Reyna Moguel, Regionalización para el Estado de Oaxaca. Análisis comparativo. Oaxaca, Centro de Sociología, IIS, UABJO, 1979.

⁶ Arturo Ortiz Wadgymar, Aspectos de la economía del Istmo de Tehuantepec. México, Instituto de Investigaciones Económicas, UNAM, 1971.

⁷ Jorge Tamayo López Portillo, Geografía moderna… op. cit.

⁸ Anya Peterson Royce, Prestigio y afiliación en una comunidad urbana; Juchitán, Oaxaca. México, Instituto Nacional Indigenista, 1975 (Col. SEP-INI, 37).

⁹ Jorge Tamayo López Portillo, Geografía moderna… op. cit. p. 58.

¹⁰ Ibid., p. 383.

¹¹ Arturo Ortiz Wadgymar, op. cit.

¹² Rafael Carrasco Puente, Bibliografía del Istmo de Tehuantepec. México, Depto. de Información sobre el Extranjero, Sría. de Relaciones Exteriores, 1948 (Monografías mexicanas, 2 series, núm. 1).

¹³ Francisco de Burgoa, Geográfica descripción de la parte septentrional del Polo Ártico de la América y nueva iglesia de las Indias Occidentales. México, Archivo General de la Nación, 1939, publicaciones 25, 26 (1a. edición, 1654).

¹⁴ Fernando de Zúñiga y Cortés, “Tehuantepec, conjunción de pueblos” en El Universal. México, magazine año XXX, tomo CXVIII, núm. 17717, 19 de mayo de 1946, p. 1-2. Véanse también distintas informaciones que se incluyen en la obra de Rafael Carrasco Puente, op. cit.

¹⁵ Enrique Méndez Martínez, Arqueología del área huave. México, tesis de maestría, Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 1975.

¹⁶ James R. Forster, “Notas sobre la arqueología de Tehuantepec”, en Anales del INAH, vol. VII, México, Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 1955, pp. 77-100.

¹⁷ It should be clarified that nothing is known about the origin of the so-called “archaic” cultures of Mexico, since as if by magic they appear as intensive farmers and potters, hence why archaeologists prefer to call that period “middle culture”, terminology with which not everyone agrees.

¹⁸ Román Piña Chan, Una visión del México prehispánico. México, Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas, UNAM, 1967.

¹⁹ The name Zapotec comes from the name of its main city Teotzapotlan, capital of the province of Tzapotecapan. Véase a Rémi Siméon, Diccionario de la lengua náhuatl, o mexicana. México, Siglo XXI, 1977 (Colección América Nuestra, América Antigua, 1).

²⁰ There are different opinions about how the Zapotecs came to populate the Valley of Oaxaca and many agree that they came from the north.

²¹ Agustín Delgado, “La secuencia arqueológica en el Istmo de Tehuantepec”, en Los Mayas del sur y sus relaciones con los nahuas meridionales. VIII Mesa Redonda (1959), México, Sociedad Mexicana de Antropología, 1961, pp. 93–104.

²² Seminaristas de Tehuantepec, “Investigaciones de campo en Tehuantepec, II”, en Estudios indígenas. México, Centro Nacional de Pastoral Indígena (CENAPI), marzo de 1973, pp. 387–412 (Cuadernos trimestrales, 3).

²³ Agustín Delgado, op. cit.

²⁴ John Tutino, “Rebelión indígena en Tehuantepec”, en Cuadernos Políticos, 24. México, Ediciones Era, abril–junio, 1980, p. 92.

²⁵ Historia de Oaxaca… op. cit., vol. 1, p. 200.

²⁶ Bernal Díaz del Castillo, Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España. México, Editorial Porrúa, 1976 (Sepan Cuantos, 5) (1a, edición, 1632).

²⁷ John Tutino, op. cit.

²⁸ Ibid., p. 94

²⁹ Arturo Dubson Lasky et al., Servicio social en el ayuntamiento popular del municipio de Juchitán, Oaxaca. Informe de actividades. México, Departamento de Atención a la Salud, División de Ciencias Biológicas y de la Salud, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana –Xochimilco, 1983.

³⁰ “El problema de los indígenas” en Neza Cubi, revista literaria y de cultura. México, Talleres Gráficos de México, marzo–abril, 1969, p. 17 (publicación bimestral, 6). Tomado de Novedades, jueves 3 de abril de 1969, p. 9.

³¹ Arturo Dubson Lasky et al., op. cit.

³² Poder Ejecutivo Federal, Plan Nacional de Desarrollo 1983–1988. México, Secretaría de Programación y Presupuesto, 1983.

³³ Abel Estrada Fentanes, La economía del estado de Oaxaca, México. Investigación del Sistema de Bancos de Comercio, 1968 (Colección de estudios económicos regionales).

³⁴ Mercedes Olivera, Los zapotecos actuales. México, INAH–SEP. 1967 (Culturas de Oaxaca, 11).

³⁵ Arturo Dubson Lasky et al., op. cit.

³⁶ There are really few studies on the social classes in the Oaxacan isthmus and we will only have to refer to them in terms of: proletariat, peasants (poor and impoverished) and bourgeoisie (agricultural or urban). Justifying each one of the mentioned categories requires a very deep discussion that is not possible here.

³⁷ Gabriel Moedano N., “Formas tradicionales de trabajo comunal en México”, Estudios Sociológicos (Sociología del trabajo y del ocio). México, IIS, UNAM, 1962, pp. 159–169 (XII Congreso Nacional de Sociología).

³⁸ According to Gudelia Pineda Luna, guendalizaa is made up of two words: guenda, between, and lizaa, blood or political relatives. Interview conducted in Mexico City in January 1984. Véase también Miguel Covarrubias, El sur de México. México, Instituto Nacional Indigenista, 1980, p. 422 (Clásicos de la Antropología Mexicana, Colección INI, 9).

³⁹ Eustaquio Jiménez Girón, Guía gráfico–fonémica para la escritura y lectura del zapoteco. Pa sicca rica diixaza xti guidxiguié’. Cómo se escribe el zapoteco de Juchitán. Juchitán, Oaxaca, Editorial Victoria Yan, p. 82.

⁴⁰ Ibid., p. 83.

⁴¹ The multiple activities carried out by the Isthmus companies can be verified, for example, in deed number two thousand eight hundred and seventy-seven, Vela “Calvario”, Juchitán, Oaxaca, 29 de noviembre de 1976. (Al margen: impreso el Escudo Nacional de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos. México, Dirección General de Asuntos Jurídicos, Exp. 439047) (Copia fotostática en poder de la autora).

⁴² “Guzana: each of the women who form a brotherhood; guzanagola: the old woman or the adult woman who heads it”, according to don Eustaquio Jiménez Girón en su obra Guía gráfico–fonémica… op. cit., pp. 95-96.

⁴³ In the main festivities of May, according to Mr. Victoriano López, a series of candles is celebrated for eight or nine days; within them there is a special afternoon in which a parade is held and flowers are brought to the church; go the piteros, the fishermen who cast their cast nets on the people who gather on the sidewalks watching the allegorical floats go by and the profusely decorated teams, pulled by oxen. The women, in their embroidered costumes, give away plastic toys; Previously, fruit from the season was thrown and for this reason the entire parade is still called “fruit throw”. Interview conducted in Mexico City in February 1979. From now on this informant will be referred to as V.L.

⁴⁴ Within the socio-political organization of the neighborhoods, the hierarchies are: the xuana or principal of the neighborhood, considered as councilor and watchman of order. One of his main functions is to request the hand of the bride, to be an intermediary in marriages with problems and to request masses for his neighborhood; the chagola, the elderly or adult person who is commissioned for the reconciliation of a marriage and the guzanas and guzanagolas. In the past, there were other positions – whose functions I have not yet clarified – such as gunixi, gunixigola, guzegola (who later became a deputygola or president), gulaba and ronda. Each of these designations requires extensive study. See: Seminaristas de Tehuantepec, op. cit., p. 345; Eustaquio Jiménez Girón, Guía gráfico–fonémica… op. cit.; Pbro, Nicolás Vichido Rito, “Algunos personajes significativos en las tradiciones zapotecas de los barrios de Tehuantepec, Oax.”, en Fiestas tradicionales del Istmo de Tehuantepec, Oaxaca. México, FONADAN (s/a, s/p).

⁴⁵ Samuel Villalobos, “A propósito de nuestras velas”, en Alberto Cajigas Langner, El folklor musical del Istmo de Tehuantepec. México, D.F., Imprenta Manuel León Sánchez, S.C.L. 1961, pp. 196–199.

⁴⁶ Entrevista realizada a don Eustaquio Jiménez Girón en Juchitán de Zaragoza, Oaxaca, en agosto de 1979.

⁴⁷ Según el informante V.L.

⁴⁸ Ibid.

⁴⁹ Eustaquio Jiménez Girón, Guía gráfico–fonémica… op. cit., p. 66.

⁵⁰ See: Gilberto Orozco, “Tradiciones y leyendas del Istmo de Tehuantepec”, en Revista Musical Mexicana, México, Talleres Gráficos de la Nación, 1946, pp. 1–251; Seminaristas de Tehuantepec, op. cit., Alberto Cajigas Langner, op. cit.; Pbro. Nicolás Vichido Rito, Costumbres matrimoniales en el istmo zapoteca (las originales). Tehuantepec, Oaxaca (texto mecanografiado s/a); Nicolás Vichido Rito, Costumbres del Istmo de Tehuantepec con relación al bautismo y matrimonio. Tehuantepec, Oaxaca (texto mecanografiado s/a).

⁵¹ Of course, there are no archaeological remains that testify that the ancient Zapotecs used flutes made of reeds; although they could well take advantage of this material for musical effects. We only know for sure that the Istmeño Zapotecs used bone flutes, proven by some archaeological findings. For example, in the explorations carried out by Agustín Delgado in the “Bomba”, Tehuantepec, a bone flute was found with engraved elements that represent “a deer pierced by a dart, it also has in its decoration a tether of years”, numerals . In these same explorations, copper rattles and tripod figurines made in mold as whistles were also found, these offer relationships with other cultures. See: Agustín Delgado, op. cit., pp. 99–100.

⁵² Fray Juan de Córdova, Vocabulario Castellano–Zapoteco, México, INAH, 1942 (primera edición, 1578).

⁵³ The Zapotec of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec is part of the linguistic complex that has been designated by various researchers as “the macro-Otomanguean group”. See: la obra de Miguel Covarrubias, op. cit., p. 376, y la “Introducción y Notas” de Wigberto Jiménez Moreno al Vocabulario Castellano–Zapoteco, del padre Córdova, p. 21.

⁵⁴ It should be noted that in Europe the names of guitar and vihuela were used interchangeably, but we must remember that the vihuela had six strings, just like the current guitar, while the guitar only had four. The origin of the word guitar is much discussed; One thesis says that it comes from the Arabic “quitära”, to distinguish the “Latin guitar” from the “Moorish guitar”. Data taken from the work of Simón Tapia Colman, Cultura musical, third part. Mexico. General Coordination of Artistic Education of the INBA–SEP, s/a. pp. 49–50.

⁵⁵ The marimba is an idiophone instrument of the xylophone order, it has wooden keys, a sound box for each key and a vibrating membrane in each resonator. The one used on the isthmus reaches the chromatic scale and is struck by three or more musicians using long sticks with rubber tips. The origin of the instrument is widely debated, but it possibly reached the isthmus via Chiapas and was later associated with instruments belonging to the band. Currently it is also heard with some electrophones. This type of instrumental associations is known as a marimba ensemble.

⁵⁶ Interview with Bartolo Gerónimo Cava in Juchitán de Zaragoza, Oaxaca, in September 1983.

⁵⁷ Interview with Fr. Nicolás Vichido Rito in Juchitán de Zaragoza, Oaxaca, in September 1983.

⁵⁸ Interview with Heberto Rasgado Ruiz in Juchitán de Zaragoza, Oaxaca, in September 1983.

⁵⁹ I clarify that the designations of trios, duos and “solitarios” are local.

⁶⁰ I use the term form in the sense of a grouping of sounds of different heights, intensities and durations, distributed and combined in a simple or complex way. Included in this concept are the forms of spoken language that in the song have a specific musical task to fulfill.

⁶¹ The great production of songs by the composer Eustaquio Jiménez Girón can be seen in La lira zapoteca, Juchitán de Zaragoza, Oaxaca, Board of Trustees of the Casa de la Cultura del Istmo, 1973.

FACE A

Nos. 1 2 and 3

As far as I know, the fragments of the lullabies that I present (and that are about to disappear) are the only examples recorded in the Zapotec language. I made a great effort to collect this type of musical tradition, which is transmitted in the first instance by the mother, who uses lullabies like those in the examples Nos. 1, 2 and 3 to put your children to sleep.

Gazi si nana is almost a forgotten lullaby, the women of the Isthmus do not remember it. The melody, in a major key, and the lyrics that my parents taught me when I was a child helped me to inquire about that song. Some Juchitec intellectuals told me it existed, but no one had any idea about it.¹

However, the search was not fruitless and can collect two interpretations of gazi si nana. The second version bears an uncanny resemblance to an old “air” or little sonnet called “The Dwarves” (see the transcript attached at the end of the pamphlet).

VERSION No. 1

GAZI SINANA (Let the nanny sleep).

Gazi si nana

gazi si tata

cuana nu mediu

chu zinu pan dxiapa

(Is repeated)

TRANSLATION

Let the nanny sleep

sleep the dad

we will steal a medium

to buy stale bread.

Performer: Vicenta Nolasco, a cappella female voice

Location: Ixtaltepec, Oaxaca

Recording date: August 1979

VERSION No. 2

GAZI SI NANA (Let the nanny sleep).

Gazi si nana

gazi si tata

cuana nu mediu

chunu ra yudu

(Is repeated)

Son son zonzo mañoso

son son zonza mañosa

Gazi si nana

gazi si tata

cuana nu mediu

chu zinu pan dxiapa

Son son zonzo mañoso

son son zonza mañosa

TRANSLATION

Let the nanny sleep

let the dad sleep

we will steal a medium

go to the church

Let the nanny sleep

let the dad sleep

we will steal a medium

to buy stale bread

Performer: Margarita Sanchez Aquino, a cappella female voice

Location: Juchitan de Zaragoza,

Recording date: August 1979

No. 3

GREGORIO. Traditional lullaby

Gueda ti xcuidi

nisi ladi

guebe dxuladi

Gregorio, Gregorio

ñe ri guba dé

pa li guchichu

zaguá li xadé

(Is repeated)

Gueda ti xcuidi…

Gregorio, Gregorio…

TRANSLATION

let the baby come

all naked

to drink chocolate

Gregory, Gregory

of ashen feet

if you give me can

I will put you under the griddle

Let the baby come…

Performer: the same as example No. 2

No. 4

PORA GULE BICU HUINI (When was the puppy born?).

Traditional son

This musical example also belongs to the group of popular “airs” that at the beginning of the 19th century were sung during intermissions in the theaters of Mexico City: after they went out of fashion among adults, children appropriated some of them. them to cultivate them in multiple variants. In this case it is the well-known little sonecito: “el atole” which, as is known, is included in “el jarabe tapatío”.

It is striking that the text of this son refers to aspects of life that other social groups hide from children, since it presents an analogy between the birth of a puppy with a “six month old”, that is, it alludes to Virginity lost before marriage, in cases where the couple hides their premarital sexual relations. This is the meaning that Mr. Eustaquio Jiménez Girón found in the text that was sung with the melody called “son del perrito” or pora gule bicu huini at wedding parties, by an ensemble made up of wound string instruments “very difficult to play”. Don Eustaquio could not tell me at what time exactly this type of group existed, currently disappeared in the area.

The real meaning of pora gule bicu huini was taken up by my informant in the text of his well-known song pumpu sin xa’na (pot-bellied bottomless pot). On the other hand, the melody of this piece is normally played by the band at the wedding parties. On this occasion I present the version that Luis Rey Sánchez, “old lucushu”, learned and sang when he was a child.

Pora gule bicu huini

guleme numba las doce

pa zuditu tobi naa

gueda záana gueta góome.

(Repeats three times)

TRANSLATION

When was the puppy born?

He was born a while ago, at twelve,

if you give me one

I will bring you an omelette so that

eat.

Performer: Luis Rey Sánchez “old lucushu”, voice and sixth guitar. Location: Juchitán de Zaragoza, Oaxaca Recording date: August 1979 The vast majority of the songs currently heard in the area contain a love theme (such as examples Nos. 5, 6, 7 and 8, Side A, and Nos. 1, 2 and 7, Side B). The great repertoire that exists with this content has preferably been based on musical forms of Spanish origin, hence this is also reflected in the poetic structure. However, it must be clarified that most of these songs are configured as true obsessions towards love and death (see examples Nos. 6 and 7 of Side B), which makes us feel the presence of an indigenous poetic tradition: Zapotec melancholy intoned with melodies that often go back –in their origin– to colonial times.

No. 5

GURIE XANA TI YAGA. (I sat under a tree).

Love song

Gurié xana ti yaga

bina sentimientu stine

ra qué zuba veda jñá

na xinga racu xine.

Nin ñabe diá jñá xiraca

rabela de que rúna ziáa

ay, hiju guca hombre

cadi gúna lu zacá.

Ay, hiju bizana laabe

zaa nube zaa cana zaa bee

guza biyubi stobi

guidxagu binni nu xpiani

cadi guidxagu binni huati

para gushidxi binni lánu.

Ay mama ma que zanda

guzana laabe

purti láabe nga ma nadxie

ora ma que guni be ni raabe

ora que guzana láabe

maca irée ma guenda biée.

TRANSLATION

I sat under a tree

crying a feeling

Own

that’s when my mother arrived

and said: what are you doing son

Own?

I did not tell the cause to me

mother

I told him I was just crying.

Oh son, be a man

don’t cry like that!

Oh, son, leave her, leave her,

go around the world!

You look for another woman

one that is smart

don’t be silly

auction

and no one will make fun of

us.

oh mom i can’t

forget her!

because she is who

love.

When I don’t do what

I ask

then i will abandon her

and I will return home.

Performer: same as in example No. 4

No. 6

The JUANITA.

Traditional istmeño son

Lyrics in Spanish: Saúl Martínez

Juana they say, Juana I say,

Juana I bring in my memory,

every time they say Juana

It seems that they say Gloria.

Oh, Juanita of my life

Joan of golden hair

always, always, I love you

always, always, I adore you.

If in your sweet dream Juana,

you hear my sad lullaby,

(Is repeated)

sleep, sleep alone and think

that my heart is yours

Oh, Juanita of my life…

Xhianga sicaru lu Juana

sica pe guié biele gazi

(Is repeated)

Juana rua ri xandié naxi

ne she cadi niziadi

(Is repeated)

Pa naa gate ne zabaane

Juana li nga xquenda biáane

(Is repeated)

Yanna what zazaya gueela

purti raabe linga xheela

(Is repeated)

I feel the soul that dies,

my heart does not beat

it’s only for Juanita,

the one I don’t know if she loves me

Oh Juanita of my life…

TRANSLATION

How beautiful you are, Juana

like a newborn flower,

Joan of Red Lips

watermelon,

always alert and not

asleep.

If I die or have life,

Juana, you live in me

memory.

Now I won’t reveal myself anymore

because you are my wife

Performer: Bartolo Gerónimo Cava “Guiati”, voice and sixth guitar

Location: Cheguigo, Juchitán de Zaragoza, Oaxaca

Recording date: August 1979

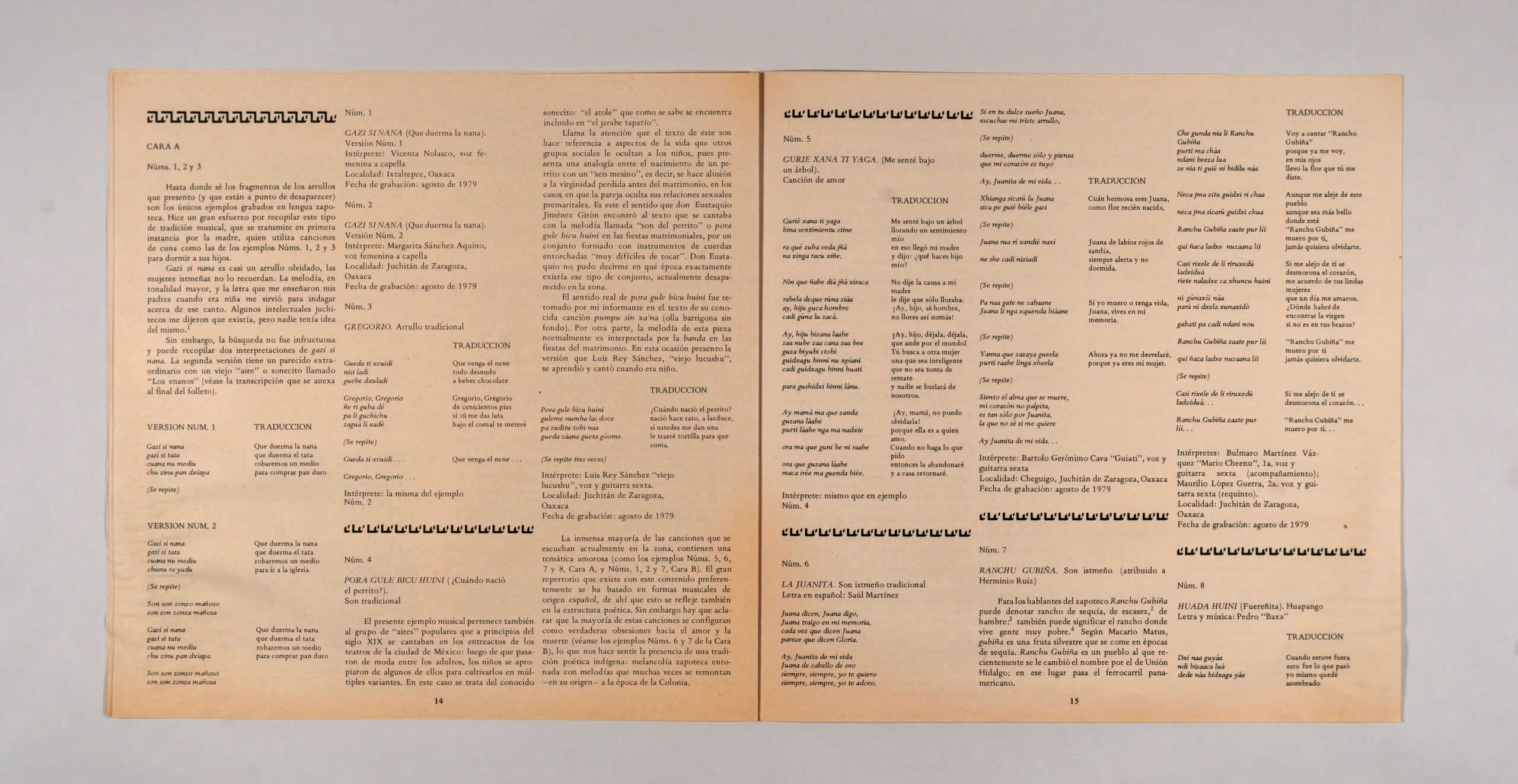

No. 7

RANCHU GUBIÑA.

Istmeno son (attributed to Herminio Ruiz)

For Zapotec speakers, Ranchu Gubiña can denote a ranch of drought, scarcity,² hunger;³ it can also mean the ranch where very poor people live.⁴ According to Macario Matus, gubiña is a wild fruit that is eaten in times of drought. Ranchu Gubiña is a town that was recently renamed Unión Hidalgo; In that place the Pan-American railway passes.

Che gunda nia li Ranchu

Gubiña

purti ma cháa

ndani beeza lua

ze nia ti guié ni bidilu náa

Neca jma zitu guidxi ri chaa

neca jma sicarú guidxi chua

Ranchu Gubiña zaate pur líi

qui ñaca ladxe nuzaana lii

Casi rixele de li riruxedú

ladxiduá

riete naladxe ca xhuncu huini

ni gúnaxíi náa

pará ni dxela xunaxidó

gabati pa cadi ndani nou

Ranchu Gubiña zaate pur líi

qui ñaca ladxe nuzaana lii

(Is repeated)

Casi rixele de li riruxedú

ladxiduá…

Ranchu Gubiña zaate pur

lii…

TRANSLATION

I’m going to sing “Ranch

gubiña”

because I’m leaving

in my eyes

I carry the flower that

you gave.

Even if I walk away from this

town

even if it is more beautiful

where i am

“Ranchu Gubiña” I

I die for you,

I would never want to forget you.

If I walk away from you

breaks the heart,

I remember your pretty

women

that one day they loved me

Where will I be

find the virgin

if not in your arms?

“Ranchu Gubiña” I

I die for you

I would never want to forget you.

you me

If I walk away from you

breaks the heart…

“Ranchu Cubiña” I

I die for you…

Performers: Bulmaro Martínez Vázquez “Mario Cheenu”, 1st. voice and sixth guitar (accompaniment); Maurilio López Guerra, 2a. voice and sixth guitar (requinto).

Location: Juchitán de Zaragoza, Oaxaca

Recording date: August 1979

No. 8

HUADA HUINI (Little outsider).

Huapango

Lyrics and music: Pedro “Baxa”

Dxi naa guyáa

ndi bizaaca luá

dede náa bidxaga yáa

guyua niá ti huada huini

quenda ganna didxastiá

(Is repeated)

Ora guiní qui riene láa

ora guinié qui riene náa

ni rune tiá ruxidxe

ne ridxiña riguidxe láa

(Is repeated)

Dxi náa guyaa

ndi bizaaca lua

dede naá bidxaga yáa

guyua niá ti huada huini

quenda ganna didxastiá

Ora guiní qui riene láa

ora guinié qui riene náa

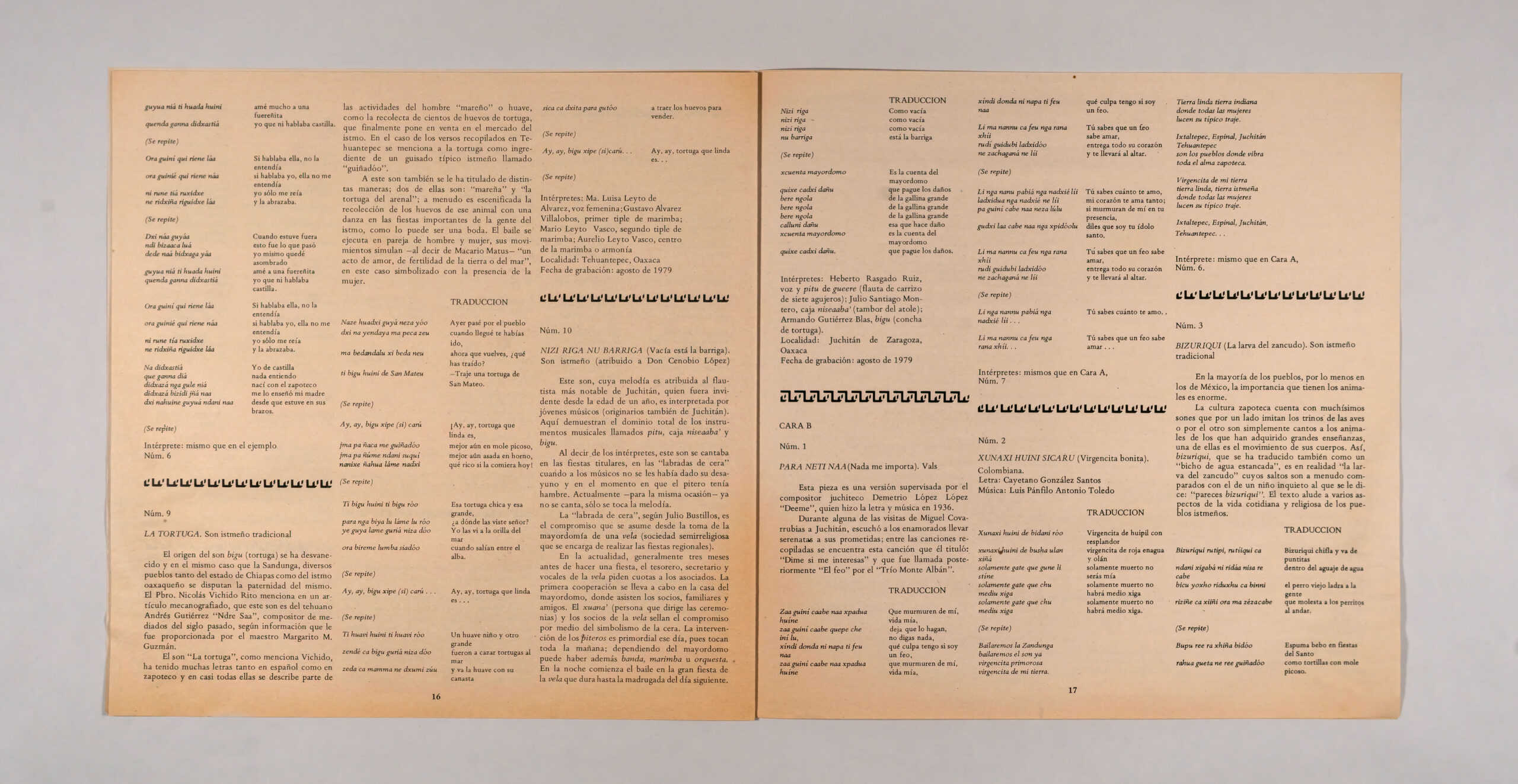

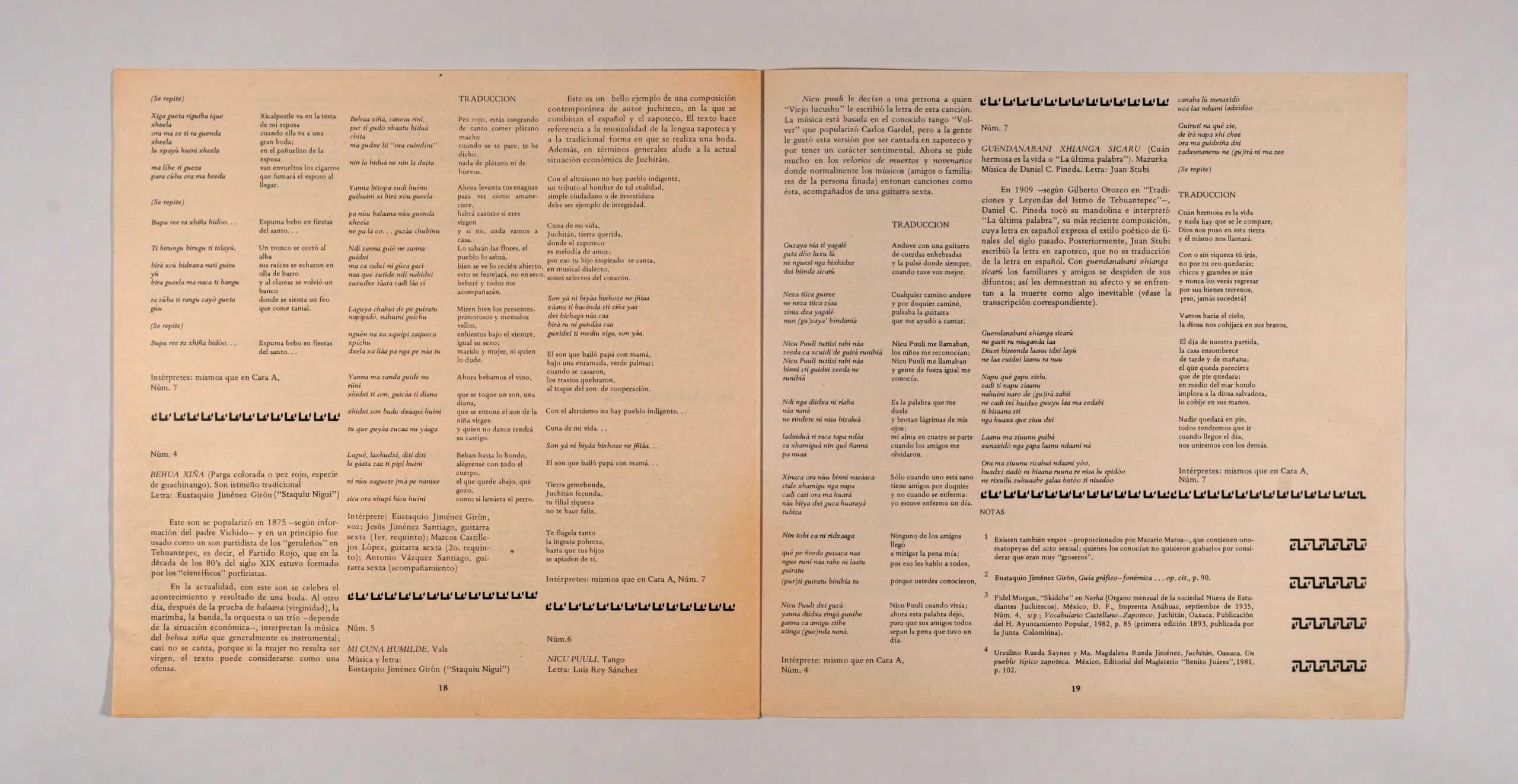

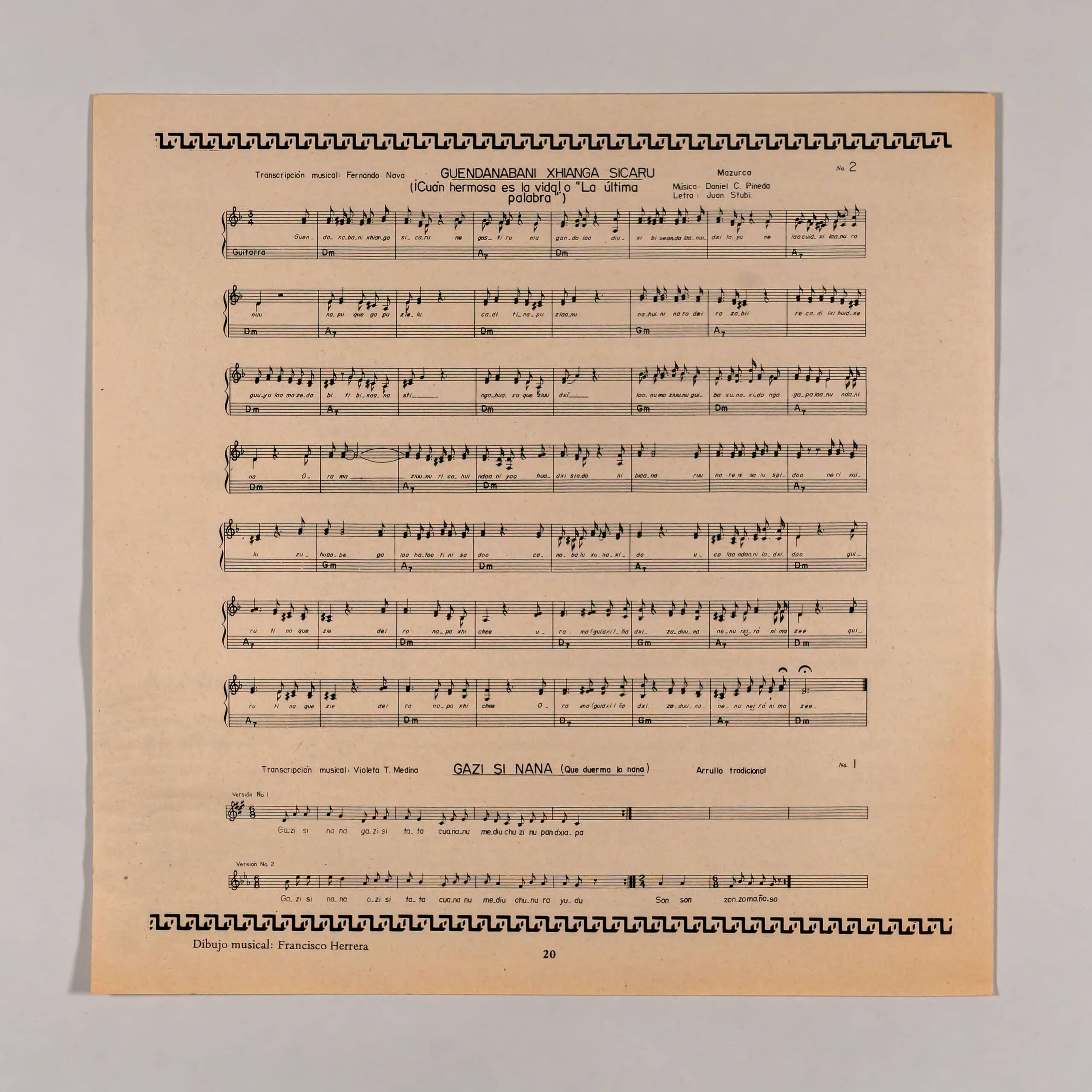

ni rune tía ruxidxe